Nietzsche’s Gift: On The First Part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra

In a note dating from 1870-71, Nietzsche referred to his own philosophy as “inverting Platonism [umgedrehter Platonismus]: the further away from true being, the more pure, beautiful, better it is” (KSA 7, 7 [156], 199). At an early stage in his career Nietzsche saw his philosophic mission as anti-Platonic. Nietzsche’s final word, however, on what this anti-Platonism would mean is not available to us. He planned to publish his ultimate philosophical magnum opus under the title The Will to Power: Attempt at a Revaluation of all Values. Nietzsche never did finish that work; what we are left with are his preliminary and fragmentary drafts toward such a work. The completed magnum opus would have been the “main structure” of his philosophy, for which Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Z) stood as a “vestibule” (Letter to Overbeck, April 1884). Although we lack the completed main structure of his thought, let us at least enter the vestibule in order to glean what we can of Nietzsche’s philosophy.[1] The portico leading to this vestibule would seem to be the theme of the gift. Nietzsche’s Z begins with Zarathustra’s determination to return to humanity, “to become man again,” in order to give the gift of his wisdom. Similarly, the First Part ends with a chapter on what Zarathustra deems the highest virtue: The Gift-Giving Virtue. Understanding this gift and this gift-giving virtue is the key to coming to grips with the overall import of the First Part of Nietzsche’s book as well as the key to coming to a preliminary understanding of the relation of his philosophy to that of Plato.

Our analysis will focus on the First Part of Z; however, the part must be understood in relation to a tentative understanding of the work as a whole. Nietzsche provides a clue to an understanding of Z as a whole: the “fundamental conception” of Z is “the idea of the eternal recurrence, this highest formula of affirmation that is at all attainable” (EH, “Books”, Z.1). The eternal recurrence is the fundamental conception of Z; however, it is not uncovered as the fundamental meaning of the whole until the Third Part. With this in mind, it is fitting to remind ourselves that Z is Nietzsche’s only dramatic work.[2] Zarathustra as a character, as well as his message, develops and changes as the drama unfolds. The claims made by Zarathustra in the First Part are provisional and form part of his own path of education on his way to becoming capable of fulfilling his final teaching. In the First Part, Zarathustra is the herald of the Overman. It is only in the Third Part that his animals refer to him as the teacher of the eternal recurrence (Z.III.13.2). Zarathustra progresses from being a herald of the Overman to the one capable of thinking and teaching the most abysmal thought, the eternal return; he progresses from herald to healer. The design motifs of the portico, then, will not be exactly those of the vestibule proper; however, we should expect some sort of design unity. Although different, the themes of the beginning and those of the end should point to one another; there will be some sort of “organic” unity to the work (Phaedrus 264c). We can expect that the claims concerning the gift and gift-giving will be provisional, corrected in the course of the work as a whole, or even within the First Part itself; yet, we should also expect that the theme of the gift in the First Part will point us toward an understanding of the ultimate teaching of Z, the eternal return.

In the First Part of Z, the theme of the gift figures forth the inversion of Platonism, as we shall see, in terms of the inversion of Plato’s form of communication. That is, Platonic communication is likened to a gift-giving that responds to the needs of its recipients. Platonic, or “esoteric,” philosophic communication adapts its message to the needs of the listener – veiling its message in order to protect listeners from harmful philosophic truths – just as some givers tailor their gifts to the needs of recipients. Zarathustra, on the other hand, learns a new form of communication and of giving in the First Part, one that is driven by the imperatives of the speaker or giver, not the listener or recipient: “How can I give each his own? Let this be sufficient for me: I give each my own (Z.I.19).” In this study I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Laurence Lampert; I follow in his footsteps in seeing Nietzsche’s work as an extended confrontation with the thought of Plato. However, it is on this point concerning the form of philosophic communication ultimately undertaken by Zarathustra that our paths part ways slightly. Whereas for Lampert Zarathustra attempts to “speak differently to different people” (1986, 45), I will demonstrate that Zarathustra learns that he must eschew this Platonic communication in the Prologue.

In taking the notion of the gift as our clue to understanding the First Part of Z, we are faced with an interpretive challenge. The gift is presented as fundamentally ambiguous, as both beneficial and destructive. Zarathustra quickly learns that not all are ready to receive the gift of his wisdom. For many, this giving will be seen as a taking; Zarathustra as giver will be indistinguishable from Zarathustra as thief. The giving of a new principle of valuation also entails the taking away of traditional standards; therefore, the role of Zarathustra as herald of this new principle is ambiguous. The essential ambiguity of the gift is rooted in Nietzsche’s language; in German the term “Gift” spans the spectrum of signification, marking both the positive and negative poles in a fashion similar to the “pharmakon” (poison / cure) in Greek.[3] In its feminine form, die Gift signifies gift or present (from the verb “geben”, meaning “to give”). In its neutral form, das Gift signifies poison (Kluge 119). Nietzsche carefully suppresses the feminine form in Z; rather than use “die Gift” in order to describe the “gift” he brings to humanity, he uses derivatives of the term Geschenk. However, Nietzsche does use das Gift and its derivatives to signify “poison” in several key instances. In this way, Part I points to Zarathustra’s role as healer, a role he will only fully assume later in Z, and points to the ambiguity of this role as well. In order to understand the essential ambiguity of Nietzsche’s gift, as it unfolds itself in Zarathustra’s roles as both herald and healer, we will examine:

- Zarathustra’s Prologue – Zarathustra begins the Prologue by announcing his intention to bring a gift to humanity. In key points in the Prologue, Zarathustra’s education is contrasted with that of the philosopher presented in Plato’s Republic. Ultimately, through the course of the Prologue, Zarathustra learns a “new truth”: that his gift to humanity will be tied to a new form of communication. He will have to “speak not to the people but to companions”.

- “On the Adder’s Bite” (Z.I.19) – This chapter contains the most significant use of das Gift (poison) in the First Part of Z. The chapter also alludes extensively to the setting and central thematics of Plato’s Phaedrus; in doing so, the art of philosophic rhetoric is likened to the art of justice in the determination of friend and enemy.

- “On the Gift-Giving Virtue” (Z.I.22) – Zarathustra’s new gift, his new form of communication, is likened to the medical art of healing in the final chapter of the First Part, which brings together the concept of the gift as it manifests itself in both Zarathustra’s role as herald and his role as healer.

- Inverting Platonism – The ambiguity of the gift has implications for our understanding of Nietzsche’s inversion of Platonism more generally.

I) The Gift Giver as Thief (Zarathustra’s Prologue)

The Prologue sets out Zarathustra’s mission as one of giving a gift to humanity. Through the unfolding of the Prologue, Zarathustra comes to learn that his gift is fundamentally tied to a new form of communication, to a new philosophic rhetoric. This new gift of communication marks a counter-movement to the philosophic rhetoric practiced by the Platonic Socrates.

Prologue 1 – That Nietzsche attempted to develop his own philosophy in a conscious agon with that of Plato is evident from the outset of the Prologue. Zarathustra is presented as an advancement upon and a reversal of the model of the philosopher ruler described in Plato’s Republic. Z opens with the following sentence: “When Zarathustra was thirty years old he left his home and the lake of his home and went into the mountains.” We could say that Zarathustra left the familiarity of his surroundings and what passed for true and false there in order to make an ascent. Whereas Plato’s philosopher rulers make an ascent out of a cave, Zarathustra’s ascent is to a cave. Zarathustra makes this ascent at the age of thirty, the age when Plato’s philosopher rulers are to be introduced to dialectic: “when they are over thirty, you will give preference among the preferred and assign greater honors . . . testing them with the power of dialectic.” Ostensibly, the wisdom Zarathustra is gathering in this ascent is as dangerous as the study of dialectic Socrates describes, wherein there is the potential that the student will be “filled full with lawlessness” (537d-e). As Z opens, Zarathustra has already spent ten years in solitude gathering wisdom. The prescribed length of time for potential philosopher rulers to study dialectic, by contrast, is only five years (539e).

After ten years of solitude, Zarathustra is prepared to make his first descent back to the realm of humans. So too, the philosopher rulers described by Socrates, after having studied dialectic for five years, return to the cave in order to gain experience in the preliminary functions of ruling: “they must be compelled to rule in the affairs of war and all the offices suitable for young men, so that they won’t be behind the others in experience” (539e). The philosopher ruler is compelled to return to the cave, whereas Zarathustra does so out of his own desire to “give away and distribute” (verschenken und austheilen) his wisdom. Philosopher rulers are to undertake the various administrative functions described above for fifteen years. At the age of fifty, philosopher rulers will then ascend again in order to behold the Good as such: “those who have been preserved throughout and are in every way best at everything . . . must be compelled to look toward that which provides light for everything.” They are then compelled to return to the city and to use the Good “as a pattern for ordering city, private men, and themselves for the rest of their lives. For the most part, each one spends his time in philosophy, but when his turn comes, he drudges in politics and rules for the city’s sake (540a-b).” Both Zarathustra and the philosopher ruler, when first returning to the cave, have yet to complete their education. The return to the cave forms part of their education, an education in the ways of men.

The philosopher ruler does not see “the source of light” until after his initial descent; however, Zarathustra has been greeting a source of light every morning during his ten years of solitude. The sun is the over-riding image of Plato’s teaching in the Republic (Books VI – VII; cf. the Phaedo 99d-100a). The sun represents the highest being and highest object of knowledge for the philosopher: the Good as that which allows beings to be as such. Zarathustra’s first words are to the sun. Rather than address this sun as the highest being, as “the Good,” Zarathustra calls the sun a “great star.” In other words, Z takes as his point of departure the end-point of the traditional, Platonic philosopher’s journey. The sun is the symbol of his own gift giving as well as of Zarathustra himself in his down going (untergehen). The sun will return at the end of the First Part as the golden sun encircled by a serpent on a staff given to Zarathustra by his disciples. Zarathustra can be likened to the sun in that his name, for Nietzsche, means “star of gold” (Thatcher 248; cf. Lampert 1986, 312n2). In a sense, the gift that Zarathustra brings to humanity is a new sun and a new horizon – replacing the horizon that had been dissolved, as the madman in the Gay Science asserts, in the wake of the death of God: “Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? . . . Away from all suns?” (GS 125).

According to Zarathustra, the sun gives its light, but is in need of the recipients of this gift: “what would your happiness be had you not those for whom you shine . . . you would have tired of your light and of the journey had it not been for me and my eagle and my serpent.” Just as the sun needs those who receive its gifts, so too Zarathustra descends to humanity out of a need for humanity to receive his wisdom: “Behold, I am weary of my wisdom, like a bee that has gathered too much honey; I need hands outstretched to receive it.”[4] In this way, gift giving as it is portrayed at the outset of the Prologue is akin to the justice of the philosopher ruler who gives the gift of his wisdom “for the city’s sake.” In both cases, the gift giving is a virtue or is just in relation to the particular needs of the recipient; it is a gift giving that needs appropriate recipients, just as the sun needed Zarathustra and his animals, who took the sun’s “overflow from [him], and blessed [him] for it.” We shall see that this notion of the justice or virtue of gift giving will be subtly modified by the end of the Prologue and that this modification will be made explicit by the end of Part I (Z.I.19 and 22).

Prologue 2 – During Zarathustra’s descent, he encounters an old saint (der Heilige). The saint recognizes Zarathustra from the latter’s ascent to the mountain ten years ago. He warns Zarathustra that returning to the cave with a new wisdom, a new fire, will most likely lead to him being “punished as an arsonist.” When asked why he would want to return to humanity, Zarathustra responds: “I love man.” The saint retorts that man is “too imperfect a thing. Love of man would kill [him].” Zarathustra changes his response: “Did I speak of love? I bring man a gift.” At this point the saint warns that the people “are suspicious of hermits and do not believe that we come with gifts . . . And what if at night, in their beds, they hear a man walk by long before the sun has risen – they probably ask themselves, Where is the thief going?” This negative reaction to the gift is akin to the treatment the philosopher would receive, of course, upon returning to the cave in any community other than the city in speech described by Socrates in the Republic: “And if they were somehow able to get their hands on and kill the man who attempts to release and lead up, wouldn’t they kill him?” (517a).

When defining the cause of his down going, Zarathustra changes his answer from “love” to the giving of a gift; he phrases it in the manner of an “either/or” – it is either his love of man or his desire to give man a gift that motivate his going to man. There is, obviously, a “both/and” option: that Zarathustra’s love of man motivates his desire to give them a gift.[5] We know that at the end of the First Part Zarathustra claims that he will return to man with a “new love.” Would this new love be that which replaces his current love of man – a higher love of man that persists despite the fact that man is “too imperfect a thing”? To fully understand Z we would need to come to an understanding of how this early, half spoken and then retracted, love of man relates to his shift from his love of Wisdom to a love of and affirmation of Life as at is has been fated (amor fati) (Z.I.7; Z.II.1; Z.III.16; cf. Republic 474c-75b). As we are only entering the vestibule of Nietzsche’s thought, it is too early to provide definitive answers to these questions; however, we can assert at this point that Zarathustra will be defined by a certain relation to love or eros; like Socrates, Zarathustra is skilled in the ways of love.

The saint warns that Zarathustra’s gift giving would be seen as a taking. Zarathustra confirms this fact when asked by the saint what gift he brings to man, responding: “What could I have to give you? But let me go quickly lest I take something from you!” After leaving the saint, laughing to himself Zarathustra “spoke thus to his heart: ‘Could it be possible? This old saint in the forest has not yet heard anything of this, that God is dead!’” Perhaps what Zarathustra could have taken away from the saint is his belief in God. The taking aspect of the gift, in this case, would be the destruction of old standards and truths, a destruction that is fundamentally linked to any creating. It is in this way that Zarathustra’s giving is fundamentally ambiguous or undecidable. That is, it is not merely misinterpreted as a taking or destroying by the many; rather, the gift, in its essence, is simultaneously a giving and a taking, a creating and a destroying.

A total destruction is annihilation, leaving nothing; this total destruction marks the crisis of nihilism (WTP 2). For Nietzsche, the crisis of nihilism is summed up in the observation that “God is dead.” Hegel preceded Nietzsche in making this claim; however, whereas for Hegel the death of God marks the resurrection of the divine as Spirit, for Nietzsche “God is dead. God remains dead” (GS 125). Nietzsche’s gift, Nietzsche’s ultimate philosophical position, was to have been the creation of the grounding principle upon which new values could be created in the wake of this total destruction. Zarathustra is the one who must prepare the ground for this new principle; however, Zarathustra must himself be given the education that would prepare him for this task. What Zarathustra must learn in the course of the Prologue, for instance, is that not all are ready for this gift, this new principle of valuation; he must learn that humanity as a whole is not in the grips of the crisis of nihilism. In this way, Zarathustra mirrors the madman of the Gay Science who, after announcing the death of God to those in the market place, realizes that they are not ready to hear these words: “my time has not come yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, still wandering – it has not yet reached the ears of man” (GS 125). Zarathustra, like the madman, had seen the crisis brought about with the death of God and ascended to his solitude in the mountains for ten years. At the beginning of the Prologue Zarathustra announces his descent to man under the assumption that the “tremendous event” of the death of God had made its way to the ears of man, which is why he is surprised that the saint has not heard this news. Zarathustra assumes that humanity is in the full grips of the crisis following the death of God and that they would have “hands outstretched to receive” the gift of his new teaching (Prologue 1). Zarathustra thinks the negative or destructive task has been completed. What he fails to understand at this point is that following the death of God there is a long twilight wherein the old values still hold sway in a ghostly form; the “good and the just” still uphold and monitor standards for the community, veiling themselves from the abyss over which these standards hover. It is only at the end of the Prologue (Z.Prologue.9), upon reflection on the failure of his speeches to those in the marketplace (Z.Prologue.3 – 5), that Zarathustra comes to realize that the people are not yet ready to receive his “gift” and that he “is not the mouth for these ears” (Z.Prologue.5); he comes to realize that his gift cannot be what is proper or due to man as a whole.

Prologue 6 – After Zarathustra’s speeches in the market place, the tightrope walker encounters the jester in motley clothes. The jester leaps over the tightrope walker while uttering a devilish cry. This causes the tightrope walker to lose his balance and to “plunge into the depth”, landing right next to Zarathustra. The dying tightrope walker says that he had “long known that the devil would trip [him]. Now he will drag [him] to hell.” The tightrope walker then asks if Zarathustra is there to prevent this.

Zarathustra had resisted taking away the old saint’s belief in God; however, he does take away the tightrope walker’s belief in the devil: “all that of which you speak does not exist: there is no devil and no hell.” At first the tightrope walker feels that this teaching means that man is indistinguishable from the beast, “taught to dance by blows and a few meager morsels.” However, Zarathustra asserts that there is nothing contemptible in his life since he has made danger his vocation. The tightrope walker receives this teaching as a gift and holds Zarathustra’s hand in thanks. Zarathustra’s varying treatments of the saint’s belief in God and the tightrope walker’s belief in the devil perhaps finds an explanation in Beyond Good and Evil (BGE): “’What? Doesn’t this mean, to speak with the vulgar: God is refuted, but the devil is not?’” On the contrary! On the contrary, my friends. And, the devil – who forces you to speak with the vulgar” (BGE 37). Zarathustra gives the gift of a world without hell, but is hesitant to reveal to believers that there is no God. He says, at this point at least, different things to different people.

Prologue 9 – After giving the dead tightrope walker a burial in a hollow tree, Zarathustra lay down on the ground and slept for a long time. When he awoke “Zarathustra looked into the woods and the silence; amazed, he looked into himself.” At this point, Zarathustra “saw a new truth.” This new truth comes to Zarathustra only after looking in amazement into the woods and silence of himself, not upon looking in amazement into the crowd in the market place (Z.Prologue.4) – although his new truth is certainly informed by his encounter with the many.

Zarathustra’s new truth is that he must find companions: “companions I need, living ones – not dead companions and corpses . . . Living companions I need, who follow me because they want to follow themselves – wherever I want.” Zarathustra realizes that his gift to humanity will be tied to a new form of communication. He will have to “speak not to the people but to companions.” Zarathustra’s descent to the many has shown him that his gift is for a rare few.[6] He “shall not become the shepherd and dog of a herd”; he shall not become the philosopher ruler described by Plato’s Socrates (343b-d; 375d-e; 416a; 525b). Zarathustra will lure his companions away from the herd. To “the good and the just,” the shepherds of the herd, he will appear as a robber. But what exactly will he steal? What will they hate about him? “Whom do they hate most? The man who breaks their table of values, the breaker, the lawbreaker; yet he is the creator.” At this point Zarathustra realizes that his gift of the creation of a new table of values must also entail the taking away or destruction of the old table of values.

How will Zarathustra lure companions away from the herd without speaking to the herd? In order to sift out those who are worthy, in order to separate the wheat from the tares, will he not have to communicate in such a way that harvests the entire crop? (Mt 13.24-43). Perhaps the answer to this question lies in the fact that Zarathustra will still speak to the people as such; however, he will not speak to them in a way that is suitable to the people or the many – and for this reason he will be hated and viewed as a thief. Plato and thinkers who followed him have attempted to speak in different ways to different people – the “difference between the exoteric and the esoteric, formerly known to philosophers.” This has meant communicating one’s “highest insights” to the few who are capable of coping with them, while veiling these insights from “those who are not predisposed and predestined for them” (BGE 30; cf. Strauss 1952, 7-37). To the latter group, the thinker supplies salutary fictions. We should note that Nietzsche felt Plato’s concept of “the good as such” was one such fiction or “invention” (BGE, Preface). Whereas Plato and those after him provided suitable fictions that conformed to the need for traditional values and standards of the many, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra will speak only to the few; he will not provide these fictions that are appropriate to the different types of man. As opposed to supporting the standards of “the good and the just,” his gift of rhetoric will result in the breaking of their tablets. Earlier Zarathustra had tried to change the tone of his speech and suit it to the many; he had tried to “address their pride” (Z.Prologue.5). Now, Zarathustra proclaims that never “again shall [he] speak to the people” (Z.Prologue.9); never again will he speak in a way that is appropriate to them. His teachings, then, will “sound like follies and sometimes like crimes” when they are heard by the many (BGE 30). This is the message of the jester who urges Zarathustra to leave the town: “there are too many here who hate you. You are hated by the good and the just, and they call you their enemy and despiser” (Z.Prologue.8). He will be seen as an enemy in that his giving is also a taking.

In a significant parallel, Plato also presents Socrates’ gift of wisdom as a type of taking or emptying. When Socrates enters Agathon’s house, for instance, to join the drinking party held in the latter’s honor, Agathon asks Socrates to lie down next to him so that Socrates’ wisdom might be transferred by means of their touching. Socrates answers that it “would be a good thing, Agathon, if wisdom were the sort of thing that flows from the fuller of us into the emptier . . . as the water in wine cups flows through a wool thread from the fuller to the emptier” (Symposium 175c-e). Although this is said in jest, through the course of the dialogue we learn that, as Socrates points out, he has “a sorry sort of wisdom” that involves the emptying or taking away of knowledge – not through touch, of course, but through questioning. Socrates’ gift of wisdom is tied to his knowledge of the art of love; in fact he claims “to have expert knowledge of nothing but erotics” (ta erotika) (Symposium 177d; cf. Lysis 204c). There is a certain play on words in this assertion: the noun eros (love) is similar to the verb erōtan (to ask questions). In fact, the Cratylus alludes to the seeming etymological connection between the two words (398c-e). To some extent, then, the Socratic art of love is the art of questioning or “elenchus.” This art of questioning is a taking away of supposed wisdom and a leaving of the interlocutor in a position where they are “without resources” (aporia) (Symposium 203e). In the Lysis, for instance, Socrates must demonstrate the true art of loving boys to Hippothales. The latter loves undertaking philosophic discussions with boys, but does this poorly; he sings eulogies of the boys and fills them with proud thoughts (205b-206b). Socrates, on the other hand, undertakes an elenctic discussion with Lysis and removes any pretension the latter had to wisdom. Since eros is a desire for what one lacks, this taking away of wisdom sets the boy on the path to philosophy – a desire for the wisdom he now knows he lacks (Symposium 200a; cf. Reeve).

Although both Socrates and Zarathustra are depicted as giving in a way that is also a taking away, we should note an important difference. While Socrates professes to give the gift of his wisdom out of an essential emptiness, out of a lack of wisdom, Zarathustra’s gift springs from an abundance of wisdom. Zarathustra is “the cup that wants to overflow, that the water may flow from it golden” (Z.Prologue.1). Socrates’ emptiness manifests itself in his form of communication; he eschews long speeches and insists that philosophic discussion must take the form of an elenctic question and answer (Gorgias 449b-c).[7] Zarathustra’s mode of communication, on the other hand, is the “speech.” Socrates is a questioner; Zarathustra is an orator. Lacking wisdom, being an empty vessel, Socrates can only question – or, at least, he professes to be only able to question. Overflowing with wisdom, Zarathustra composes speeches appropriate for potential companions in wisdom.

Plato presents us with his most thoughtful dialogue on the potential and the dangers of different forms of speeches (logoi) in the Phaedrus. It is also one of the rare dialogues in which Socrates composes speeches himself, and composes them out of a sense of being filled by an external source: “I am sure of this because my own heart is full and I have a feeling that I could compose a different speech not inferior to this. Now I am far too well aware of my own ignorance to suppose that any of these ideas can be my own. The explanation must be that I have been filled from some external source, like a jar from a spring” (235c-d).[8] Socrates goes on to compose one speech in defense of the non-lover, and one in defence of the lover. In doing so, as Phaedrus notes, he is “carried away by a quite unusual flow of eloquence” (238c). Nietzsche carefully mimics the setting of that dialogue in the chapter entitled “On the Adder’s Bite” (Z.I.19). In order to develop a deeper understanding of the function of the gift, in its essential ambiguity and in its connection with Zarathustra’s mode of discourse, we will now turn to that chapter.

II) The Gift as Pharmakon (I.19, “On the Adder’s Bite”)

The chapter begins as follows: “One day Zarathustra had fallen asleep under a fig tree, for it was hot, and had put his arms over his face. And an adder came and bit him in the neck, so that Zarathustra cried out in pain.” The bite of this adder and Zarathustra’s response to it form a type of parable that Zarathustra interprets for his disciples later in the chapter. The chapter, in this way, recalls the “parable of the tares” that Jesus relates to his disciples (Mt 13:24-43). More importantly for our purposes, the chapter is an evocation of the scene set in the Phaedrus, with Nietzsche changing several key features of Plato’s scene with distinctive effect.

The Phaedrus opens with the title character on his way for a stroll outside the city walls. This type of stroll outside the city had been recommended to him by Acumenus, a famous physician (227a). Let us take this early reference to the medical advice of a physician as an opportunity to remind ourselves of the Derridean analysis of Plato’s dialogue. For Derrida, the Phaedrus is the Platonic dialogue that most perspicuously raises questions surrounding the status of the pharmakon, as both poison and cure, as well as the question of the physician’s art as the medical operation of administering the poison that can also be the cure (pharmakeia).[9] The undecidability of the pharmakon silently underwrites the latent content of Plato’s entire philosophic enterprise. That is, underneath the strict dualism of the manifest text of Platonism – which posits, for example, the distinctive and clear superiority of the super-sensuous over the sensuous, speech over writing, truth over semblance etc., – there is a latent text marked by the prevalence of the pharmakon and its cognates signalling the undecidable flowing of all things into one another. Although the pharmakon underwrites Platonic philosophy generally, for our purposes we will focus on the way in which it informs Plato’s teaching concerning what is proper in speech (logos). We had occasion to mention that das Gift signifies poison. In this way, the undecidability of Nietzsche’s “gift”, especially as it relates to the question of Zarathustra’s rhetoric, will be linked to the problematic of the Platonic “pharmakon.”

Now, let us return to the Phaedrus.

Phaedrus is on his way out of the city upon having spent some time with Lysias, a renowned sophist. Lysias had taught Phaedrus a speech designed to win the affections of a boy for a non-lover. Socrates agrees to follow Phaedrus in order to hear this speech even if he walks as far as Megara “and then, in the manner of Herodicus” (another famous physician), turns straight back (227d). Socrates is willing to go to such extremes to hear this speech because he is one whose “passion for such speeches amounts to a disease” (228b). We should note here that Socrates’ passion for speeches drives him to follow the prescription of the physician Herodicus. In the Republic, Herodicus was the negative exemplum of the proper art of medicine and by extension the proper art of justice. The natural “curing” of a disease consists of the bringing forth of the natural order (health) of the body. The source (archē) of the cure is the body’s own unfolding; the technē of medical art merely consists of bringing this natural order forth.[10] Herodicus represents, for Socrates, modern methods of treating disease through the external imposition of treatments that take the patient outside of their natural course and rhythm. He contrasts this modern method of pharmakeia with the legendary time of Asclepius, a time in which the healing art meant this appropriate bringing forth of the natural order of the body, not the attempt to impose an external order (Republic 405d-410a).

Given this problematic of “modern medicine,” why does Socrates call on Herodicus in the Phaedrus as a guide? It seems that the dualism at play in the Republic, Asclepius’ good “cure” versus Herodicus’ bad art that is in effect a “poison,” is called into question in the Phaedrus. This is peculiar given that, on the surface at least, the task of the dialogue is the discernment of the difference between what is proper and improper in love, in the movement of the soul, and in discourse (logography). The manifest text of the dialogue does reach very clear conclusions in this regard: proper love is the intellectual love of beauty and of the forms (eidē); the proper movement of the soul is the upward way, denying the temptations of the sensual in order to join the divine banquet; and the proper mode of discourse is speech (as opposed to writing) that respects a certain organic unity. As we’ve said, a Derridean deconstruction of the dialogue reveals an undecidability with respect to these seemingly opposed terms that resides within the latent text of the dialogue. As we will see, Nietzsche penetrated this latent text of Plato in a profound way well in advance of Derrida.

Socrates agrees to follow Phaedrus on his walk and the latter is about to recite the speech of Lysias from memory; however, he is stopped by Socrates: “let me see what it is you are holding in your left hand under your cloak; I strongly suspect it is the actual speech” (228d). This description of the prelude to Lysias’ speech is alluded to in the chapter preceding “On the Adder’s Bite”, entitled “On Little Old and Young Women” (Z.I.18). In that chapter, Zarathustra is stopped by one of his followers who asks: “Why do you steal so cautiously through the twilight, Zarathustra? And what do you conceal so carefully under your coat? Is it a treasure you have been given? Or a child born to you? Or do you yourself now follow the ways of thieves, you friend of those who are evil?” Zarathustra’s response reveals that what he hides under his coat is a discourse of sorts; it is a message, “a little truth” that he carries. In the Phaedrus, Socrates asks his interlocutor to reveal a speech that is hidden under his cloak; in Z, on the other hand, Zarathustra is asked by one of his followers to reveal what is hidden under his coat. Zarathustra says that it is “like a young child” in that if Zarathustra does not hold his hand over its mouth “it will cry overloudly.” The message Phaedrus conceals concerns the superiority of the non-lover over the lover. The message that Zarathustra conceals concerns how one should love, or at least relate to, women: “You are going to women? Do not forget the whip!” Later in the Phaedrus, discourse will be compared to a child that is in need of its parent (speaker/author); so too is Zarathustra’s little truth compared to a child. In the Phaedrus, the child-discourse needs the parent-speaker lest it be misinterpreted. Similarly, Zarathustra must tend to the child-discourse he carries; the child’s crying is overloud and could be misinterpreted as simple misogyny. What is at stake in this “little truth” is actually much more comprehensive; it concerns the way of relating to and loving beings a whole, here symbolized by “woman.” Zarathustra’s little truth points to the teaching that will form the central message of the Second Part of Z: the will to power. The episode also points to the Second Part in that Zarathustra will realize that his teaching has become distorted, forcing him to adopt a “new speech” (Z.II.1). This symbolic allusion to the need to suppress a message that could be negatively misconstrued points to a change in the approach and in the portent of the teaching that will take place in later parts of Z (cf. Z.II.1, 20). The preceding insight highlights what we might call a guiding principle for the interpretation of Z: the unfolding of the symbolic register as well as the forms of communication utilized by Zarathustra anticipate and point to future developments with respect to the content of the ultimate teaching of Nietzsche’s work as a whole.

Socrates and Phaedrus make their way along a stream in the countryside surrounding Athens in order to find a suitable spot to sit and listen to the speech of Lysias. They find a perfect location under a plane tree that will provide shade during a very hot day (242a, 259a). In “On the Adder’s Bite”, Zarathustra similarly finds rest and shade under a tree on a very hot day. Socrates and Phaedrus find shade under a plane tree; Zarathustra does so under a fig tree.[11] Although this was not the lens through which Plato would have regarded the plane tree, within the Christian tradition, to which Nietzsche was extensively exposed, the plane tree signifies the gift as such; it represents the Christian charity that surpasses the pagan charity of the ancient world. The fig tree, on the other hand, represents a certain shame or concealment – given that our first ancestors used the leaves of that tree “To gird their waist, vain covering if to hide / Their guilt and dreaded shame” (Paradise Lost, IX.1113-14; cf. Genesis 3.7).[12] After Phaedrus relates the speech of Lysias, Socrates provides his own speech in defence of the non-lover, which, he insists, is better structured. Socrates presents this speech with his face covered so that he won’t be “put out by catching [Phaedrus’] eye and feeling ashamed” (237a). The potential shamefulness of discourse would appear to be one of the central concerns of the Phaedrus as a whole: “At the precisely calculated center of the dialogue – the reader can count the lines – the question of logography is raised (257c). Phaedrus reminds Socrates that the citizens of greatest influence and dignity, the men who are the most free, feel ashamed (aiskhunontai) at ‘speechwriting’” (Derrida 1981, 68). Like Socrates, Zarathustra covers his face, but does so while sleeping not while speaking. There is no shame in Zarathustra’s speeches; he only speaks what is proper to himself – what he can own and own up to – but there may be shame or concealment in the dramatic contexts of his speeches.

After giving his own speech, Socrates is about to leave; however, he is stopped from leaving by a sting of conscience, so to speak. His daimon stops him from leaving, as his speech was a sin against love (242c). The bite Zarathustra receives, on the other hand, is a prompt for him to go, not to stay. Zarathustra’s bite occurs while he is inside the city and he relates the import of this incident to his disciples, to a many, or at least to a few. Socrates’ bite, on the other hand, occurs while he is outside the city – significantly, the only occasion within the Platonic dialogues in which Socrates is depicted outside the city – and it occurs while he is discussing with one person.

As we can see, there are significant echoes and reversals of the Phaedrus in the chapter “On the Adder’s Bite.”[13] Most significant, however, is the way in which the two texts treat the problematic of the opposite values contained within the pharmakon or Gift. In the Phaedrus, Plato’s Socrates attempts to secure the play of the pharmakon within a dualism and fixed hierarchical relation: intellectual over sensual love, cure over poison, speech over writing. In “On the Adder’s Bite”, on the other hand, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra embraces the intermixing of these terms. Zarathustra stops the adder before it leaves in order to thank him for his gift: “as yet you have not accepted my thanks. You waked me in time, my way is still long.” The adder responds that Zarathustra’s way is short as his poison kills (mein Gift tödtet). Zarathustra receives the adder’s poison (das Gift) as a beneficial present worthy of thanks (die Gift). When asked by his disciples what the meaning or “moral” of this story is, Zarathustra answers that the story is “immoral”; it is outside of the metaphysical oppositions that ground conventional morality; it is “beyond good and evil.”

The implication of this immoral moral is that Zarathustra teaches a new justice in terms of the proper way of dealing with friends and enemies. A Socratic definition of justice might be: giving to each what is due, or what is their own; or, giving benefit to friends and harming enemies.[14] The Christian manifestation of this form of justice is the injunction to “turn the other cheek” when harmed by an enemy. This form of justice results in harming the enemy, for Nietzsche, by bringing shame upon the enemy (Rom 12.20; cf. Z.I.17). Zarathustra teaches, on the other hand, “if you have an enemy, do not requite him evil with good, for that would put him to shame. Rather prove that he did you some good.”

This question of how to relate to enemies and friends, of course, has a bearing upon the new type of philosophic rhetoric that Zarathustra institutes. Within the philosophic tradition, justice in communication has meant speaking differently to different types of people. To those few friends that are capable, the philosopher provides the truth of his “highest insights”. To others, the philosopher provides a lie or a fiction. As Zarathustra points out, with the one “who would be just through and through even lies become kindness to others.” For this reason, Socrates recommends the use of the lie as it is “useful against enemies, and, as a preventive, like a drug (pharmakon), for so-called friends when from madness or some folly they attempt to do something bad” (Republic 382c).[15] It is this type of just philosophical communication that Zarathustra eschews: “But how could I think of being just through and through? How can I give each his own? Let this be sufficient for me: I give each my own.” Rather than give to each what is due, what is their own – that is, lying to some while speaking truthfully to others – Zarathustra will speak in only one fashion. Zarathustra’s speech will be based on what is appropriate and true to him alone. Zarathustra hereby extends and makes explicit the underlying assumptions of the “new truth” that occurred to him at the end of the Prologue. It is a new truth that is at odds with the notion of giving presented at the outset of the Prologue, which assumed Zarathustra’s communication of his gift would respond appropriately to the needs of his recipients. In addition, this discussion of Zarathustra’s giving “each [his] own” provides some clarity to Zarathustra’s earlier speech “On Reading and Writing”; that is, his speaking, like an aphoristic writing, is addressed only to the “tall and lofty” (Z.I.7; cf. PTG 7; HH “Wanderer and His Shadow” 71).[16]

The argument underlying the traditional mode of philosophic rhetoric is spelled out in the Phaedrus. Thus, in addition to the setting, the chapter “On the Adder’s Bite” is also evoking the central concerns of that dialogue as a whole. After the speeches in defence of the non-lover and in defence of the lover, the discussion turns to what is proper and improper in speech and in writing. Socrates presents a “tradition (mythos) handed down from men of old” (274c), that is intended to explain the inferiority of writing to speech. It is a tradition that comes from Egypt concerning the inventions of the god Theuth, among which were “number and calculation and geometry and astronomy, not to speak of various kinds of draughts and dice, and, above all, writing.” Theuth presents these inventions to the king of the gods, Thamus, also called Ammon. After presenting the various other inventions, “when it came to writing, Theuth declared: ‘Here is an accomplishment, my lord the king, which will improve both the wisdom and the memory of the Egyptians. I have discovered a sure recipe (pharmakon) for memory and wisdom.’” The king replies that Theuth, as the “father of writing” and “out of fondness for [his] offspring,” has misjudged the nature of his invention. For Thamus, those who learn the art of writing “will cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful; they will rely on writing to bring things to their remembrance by external signs instead of on their own internal resources” (274c-75b). Socrates then provides his interpretation of Thamus’ judgement in relation to writing:

“The fact is, Phaedrus, that writing involves a similar disadvantage to painting. The productions of painting look like living beings, but if you ask them a question they maintain a solemn silence. The same holds true of written words; you might suppose that they understand what they are saying, but if you ask them what they mean by anything they simply return the same answer over and over again. Besides, once a thing is committed to writing it circulates equally among those who understand the subject and those who have no business with it; a writing cannot distinguish between suitable and unsuitable readers. And if it is ill-treated or unfairly abused it always needs its parent to come to its rescue; it is quite incapable of defending or helping itself” (275d-e).

Writing, as opposed to the living exchange of speech, is a dead letter, unresponsive to questioning. In addition, it says the same thing to all; it does not distinguish its audience and determine what is appropriate or suitable to each. Since Plato presents this Socratic argument against writing within his own written text, we “may assume that the Platonic dialogue is a kind of writing which is free from the essential defect of writings.”[17] In order to be free from these defects, Plato’s writings would need to be living documents that distinguish the appropriate needs and questions of its audience in different contexts and times. As we have seen, in the First Part of Z a reversal of this form of Platonic communication is effected; rather than a writing that speaks differently to different readers, Zarathustra professes a speech akin to aphoristic writing that says the same to all and truly addresses only those who are tall and lofty.

Like Derrida, Nietzsche exposes the undecidable play of opposites that is affirmed in the heart of Plato’s text. For Derrida, however, this undecidability is an effect of the unconscious play of differential linguistic relations, of différance. For Nietzsche, on the other hand, this play is the product of the consciously esoteric form of Platonic philosophy. That is, both Nietzsche and Derrida, uncover a latent text of undecidability underneath the manifest text of Platonism with its strictly defined dualisms. For Derrida, this means reversing the hierarchical dualisms of the manifest text of Plato in order to uncover a play of differences that had eluded Plato the author. Nietzsche, however, was profoundly aware that Plato wore masks. He was aware that the undecidability underneath the exoteric text is the core of Plato’s esoteric teaching. In this way, Zarathustra only reverses the mask of “Platonism” in the First Part of Z; he affirms Plato as such.

III) The Symbol of the Gift (I.22, “On the Gift-Giving Virtue”)

At the end of the First Part of Z, we find Zarathustra bidding “farewell to the town to which his heart was attached.” Zarathusta leaves The Motley Cow and “many who called themselves his disciples followed him.” Upon coming to a crossroads, Zarathustra informed his disciples that he “wanted to walk alone.” The disciples must have known that this moment was coming, for the narrator describes for us no sign of surprise, let alone despair. Indeed, they have even prepared for this occasion a parting gift: “His disciples gave him as a farewell present a staff with a golden handle on which a serpent coiled around the sun.” The staff that the disciples give to Zarathustra is the ultimate symbol of the meaning of the gift and of the gift-giving virtue; it spurs Zarathustra to deliver three speeches on the theme of the gift. Let us, therefore, focus on this symbol and what its ultimate import may be in regards to the ambiguity of the gift we have been exploring.

The symbol of the staff is connected to the figure of Moses, one who delivered the Jewish people from the bondage of Egypt and led them to the Promised Land.[18] In the Christian tradition, Moses is typologically identified with Christ – as Moses delivered the Jews from physical bondage, so too has Christ delivered all from spiritual bondage.[19] Is Zarathustra also akin to one who has delivered his disciples from a type of bondage; is his gift one of freedom from slavery of sorts?

In terms of the relation between the symbol of the gift and the Platonic themes we have been pursuing, the figures on the staff’s handle can be remotely linked to the myth of writing provided by Socrates at the end of the Phaedrus. The sun is a symbol for the god Thamus, also known as Ammon or Ra. The serpent is a symbol for Theuth, by means of Theuth’s equivalent Hermes. In the myth, the inventive knowledge of Theuth (the serpent) serves the higher power of Thamus (the sun) in a hierarchical relation of sorts; however, in Z the two are entwined; the serpent is coiled around the sun, not subservient to it.

The staff and the figures on its handle also evoke the symbols of the herald as well as of the healer (Hermes and Asclepius). The caduceus is the staff carried by Hermes and was the same staff often carried by heralds in general. It is a short staff entwined by two serpents and topped by wings. The Rod of Asclepius is also similar to the gift given to Zarathustra. It consists of a staff entwined by a serpent. Asclepius, son of Apollo, was the god of healing and his rod has become the symbol of the healing or medical arts (Thatcher 247). In short, the symbol of the gift that we see at the end of the First Part of Z brings together Zarathustra as herald and Zarathustra as healer – as well as all of the ambiguities with each of these roles we have outlined above.

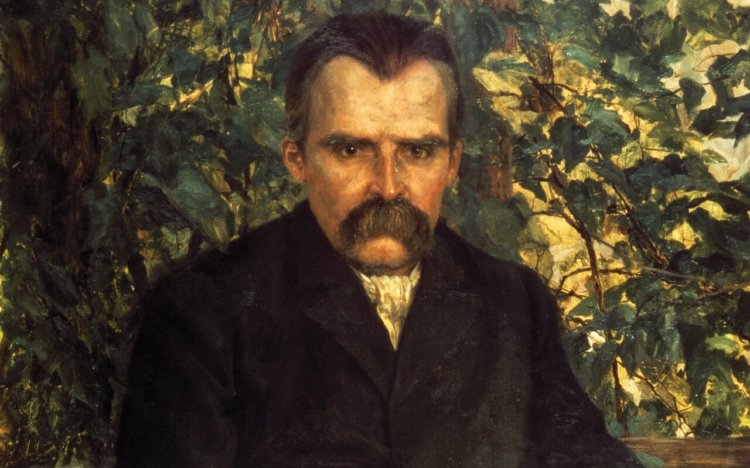

Figure 1: The Caduceus and the Rod of Asclepius

Through the course of the work as a whole, Zarathustra will become capable of providing the spiritual cure for humanity that is required due to the crisis of nihilism. The symbol of the gift presented in the last chapter of Part I points to this future role of Zarathustra as healer. Zarathustra will bring a new art of healing parallel to the new justice described above. Rather than giving to each what is proper to them, Zarathustra asserts that he will “give each [his] own” (Z.I.19). Similarly, Zarathustra will not follow the classical standards of healing, wherein true medical art entailed responding to the particular needs of each patient – as opposed to following a prescription that applies the same standard to all (Statesman 294a-b, 296b-c). Rather, Zarathustra’s healing begins by adhering to the standards of the physician himself, not by responding to the specific needs of a patient: “Physician, help yourself: thus you help your patient too” (Z.I.22.2). The importance of this image of Zarathustra as healer in relation to the crisis of nihilism becomes more concrete once we remind ourselves of the definition Nietzsche often applied to the philosopher, as well as to his own philosophic mission: “physician of culture” (PTG 1).

Zarathustra’s new mode of healing – as per his new mode of philosophic rhetoric and justice – is developed in contradistinction to that of the Platonic Socrates. For Nietzsche, Socrates only “seemed to be a physician, a savior.” In the days leading up to his death, even Socrates recognized this ambivalence concerning his character: “‘Socrates is no physician,’ he said softly to himself; ‘here death alone is the physician. Socrates himself has merely been sick a long time’” (TI, “Problem” 11-12). In reality, Socrates was a disease, a disease that unfolded itself into its most acute case in the form of the modern crisis of meaninglessness. Socratism, as articulated more fully in “Platonism”, is the disease; Nietzsche saw himself as the physician best positioned to “cure” this disease and saw Zarathustra as his mouthpiece for this cure.

The sun and the serpent on the staff given to Zarathustra are also an echo of Zarathustra’s animals described in the Prologue: the eagle and the serpent. At the end of the Prologue, Zarathustra looked into the air and there he saw an eagle that “soared through the sky in wide circles, and on him there hung a serpent, not like prey but like a friend: for she kept herself wound around his neck” (Z.Prologue.10). The serpent on the handle of the gift wraps itself around the sun; in the Prologue, a serpent wraps itself around an eagle. The eagle is a “solar” symbol in many traditions (Thatcher 245), so the two images should be considered together.[20] For our purposes, the question that arises in the first place is why, between the beginning and the end of the First Part, the eagle is replaced by the sun in this image of the gift? The eagle, for Zarathustra, is the “proudest” animal, while the serpent is the “wisest” animal (Z.Prologue.10). At the end of the First Part, Zarathustra describes the two figures on the handle of the staff (sun and serpent) in relation to power and wisdom: “Power is she, this new virtue; a dominant thought is she, and around her a wise soul: a golden sun, and around it the serpent of knowledge” (Z.I.22.1). Between the beginning and the end of the First Part, Zarathustra’s animal images of the gift have changed in one area: pride has been replaced by power; the eagle replaced by the sun. At the beginning of the Prologue, gift giving was seen as something that needed appropriate recipients with “hands outstretched”; gift-giving could be a source of pride in the giver, who would receive “thanks” from the recipient. At the end of the First Part, the gift is given out of the autonomous overflow of power on the part of the giver, not in response to any need of the recipient. Elsewhere, Nietzsche describes this noble sentiment of giving out of an internal sense of exceeding wealth in the following way: “the happiness of high tension, the consciousness of wealth that would give and bestow: the noble human being, too, helps the unfortunate but not, or almost not, from pity, but prompted more by an urge begotten by excess of power” (BGE 260).[21]

The fact that the eagle has flown away recalls the end of the Prologue in another sense. Zarathustra had closed the Prologue by prophesying the following: “And when my wisdom leaves me one day – alas, it loves to fly away – let my pride then fly with my folly” (Z.Prologue.10). The figures on the staff given to Zarathustra silently point to a future wherein Zarathustra’s wisdom will have left him. The symbol of the gift points to a “new love” that Zarathustra will embrace: replacing his love of Wisdom with a love of Life and of the eternal recurrence (Z.III.16). However, before this new love can be embraced, Zarathustra will need to return to humanity with a “new speech” (Z.II.1), one that recognizes that with “hunchbacks one may well speak in a hunchbacked way” (Z.II.20) – a new philosophic rhetoric that once again attempts to speak differently to different people. This new speech will be appropriate to the changing context and content of his teaching; that is, in the Second Part, Zarathustra’s teaching is that the Being of all beings is the will to power; the audience for this teaching will move from his disciples, to the “wisest,” and finally to himself alone.

IV) Inverting Platonism

Nietzsche’s gift is grounded in an understanding of the essence of the Western tradition as Platonism, a Platonism that has unfolded itself in the form of nihilism. Nietzsche’s gift, as presented in the First Part of Z, is an overturning of Platonism as a means by which to chart a path through the desert of nihilism. We have concentrated on Zarathustra’s overturning of Plato’s mode of communication, but how does Part I of Z point us to what “inverting Platonism” ultimately means within the content of Nietzsche’s thought? To understand this fully, one would first have to come to grips with what Platonism means for Nietzsche and then with what inverting or reversing Platonism would then mean. As an indication of the interpretive complexity involved in this task, we need only refer to the extensive and challenging interpretations of Nietzsche undertaken by Heidegger and Deleuze that take as their point of departure the question of Nietzsche’s reversal of Platonism.[22] Provisionally, we might say that Platonism is a philosophy that posits two worlds: a true world of beings in their being (eidos) and an apparent world of beings in their shadowy semblances (phantasma). To invert Platonism, in the first instance, would mean to overturn this privileging of a true over an apparent world. For Nietzsche, the world of semblance would be privileged over the supposedly “true world”; in other words, “art is worth more than the truth” (WTP 853).[23]

We must ask ourselves, however, whether Nietzsche’s relation to Platonism is merely one of reversing the terms within its hierarchical, metaphysical system – that is, if Platonism asserts the prevalence of truth over appearance and of the non-sensuous over the sensuous, is the upshot of Nietzsche’s philosophical intervention the reversal of these terms, such that we are given to prefer appearance over truth and the sensuous over the non-sensuous? Would not this type of mere reversal keep humanity trapped within the same structures and systems that we seemingly need to escape, harnessed within the type of willing motivated by the “spirit of revenge” that has led us to the modern crisis of nihilism (see Z.II.20)? This is certainly Heidegger’s view with respect to Nietzsche’s “countermovement” to Platonic metaphysics: “Nevertheless, as a mere countermovement it necessarily remains, as does everything ‘anti,’ held fast in the essence of that over against which it moves. Nietzsche’s countermovement against metaphysics is, as the mere turning upside down of metaphysics, an inextricable entanglement in metaphysics” (Heidegger 1977a, 61). To move beyond the metaphysical system as such and to provide the proper cure for the malaise of modernity, Nietzsche would need to chart a course outside of the terms of these Platonic dualisms and hierarchies; these terms would need to be “displaced” rather than simply “reversed”. For Deleuze, it is exactly this sort of displacement of the Platonic order of models and copies that Nietzsche’s philosophy institutes (1990, 265-66).

We have entered the portico of the “entrance hall” of Nietzsche’s thought, using the theme of the “gift” as our point of departure. It would be premature, at this point, to make final conclusions in terms of whether the interpreter of Nietzsche should side with Heidegger or Deleuze on the question of “inverting Platonism,” or whether another question is more appropriate to ask. However, we have seen that the symbolism and the mode of communication surrounding the gift in the First Part have pointed to developments in the content of Zarathustra’s teaching in Parts II and III. If we are not yet in a position to answer the question concerning Nietzsche’s relation to Platonism, we are at least in a position to say that the key to coming to an understanding of this issue lies in the “serial” manner in which Z unfolds. That is, Nietzsche’s gift is to provide humanity with the principle of a new valuation, which will be named alternately the will to power and the eternal return; however, he presents this gift in a serial manner. Zarathustra’s first teachings concern the overman; this implies a linear notion of existence where the present and what is small in it can be overcome and leaped over. Zarathustra’s final teaching concerns the affirmation of what is small and what causes nausea; the final teaching concerns overcoming the “great disgust with man” that had previously choked Zarathustra (Z.III.13). In this way, the First Part of Z undertakes a preliminary destruction of the old principles of valuation – the otherworldly valuations. It consists of a reversal or overturning of these principles. Previous valuations had privileged the other-worldly over the earth; Zarathustra teaches the Overman who is the “meaning of the earth.”[24] In the First Part, Zarathustra’s teaching is bound by the dualisms and structures he attempts to overthrow; however, this is not his final word on the matter.[25] The gift of the First Part is a provisional gift; the final gift will need to displace the dualisms of the tradition, rather than provide a mere reversal of those dualisms.

A displacement of the Platonic system would mean the erasure of the dichotomy, for instance, between true and apparent worlds: “The true world – we have abolished. What world has remained? The apparent one perhaps? But no! With the true world we have also abolished the apparent one. (Noon; moment of the briefest shadow; end of the longest error; high point of humanity; INCIPIT ZARATHUSTRA)” (TI, “How the ‘True World’ Finally Became a Fable” 6). By pursuing the diseased legacy of Socrates to its final fruition, by pursuing the will to the thinkability and knowability of all beings, Western science has killed God and has destroyed the Platonic fiction of a “true” world. At first, within the long twilight of that destruction, humanity perceives that the opposite values are now what reign: this is now a “humanistic” age, rather than a divine age; this is the time to celebrate things in their outward appearances, rather than in reference to their external, “true” models. However, Nietzsche’s ultimate warning seems to be that with these destructions, of God and of the true world, man as hitherto understood and the apparent world have also been destroyed.[26]

The destruction of the true and the apparent worlds implicates the search for knowledge within the same problematic: “Just now my world became perfect; midnight too is noon; pain too is a joy; curses too are a blessing; night too is a sun – go away or you will learn: a sage too is a fool . . . All things are entangled, ensnared, enamored” (emphasis added) (Z.IV.19.10). Nietzsche’s teaching concerns the truth behind the rhetoric of philosophy. The metaphysical claims, the claims to discern proper versus improper audiences, what is good or evil, true or untrue, are shown to be fictions covering over the harsh truth that existence is pure becoming, the blending together of all things, identities and what had been perceived as opposite values.[27] The First Part of Z points to this blending together of all identities and seemingly opposed values, as we have seen, by means of the circular and undecidable theme of the gift: as both giving and taking, poison and cure. Although the content of Zarathustra’s teaching in the First Part still adheres to beings with identifiable characteristics in-themselves (man and overman), the mode of his philosophic rhetoric and his symbolism point to the later teachings of the will to power and the eternal return, wherein these identities become “entangled, ensnared, enamored.” With the Nietzschean unmasking of the truth behind the pretensions of the philosophic tradition, we are left with a world where philosophy, as the pursuit of wisdom or knowledge, is impossible. It seems that Nietzsche’s gift, to borrow a phrase from Heidegger, is that he presents us with “the end of philosophy and the task of thinking.”

Abbreviations

Dates in parentheses refer to year of publication or composition.

A = The Antichrist (1888), in Nietzsche 1954, 568-656

BGE = Beyond Good and Evil (1886), in Nietzsche 1966, 179-435

BT = The Birth of Tragedy (1872), in Nietzsche 1966, 3-144

CW = The Case of Wagner (1888), in Nietzsche 1966, 609-48

D = Daybreak (1881), Nietzsche 1982

EH = Ecce Homo (1888), in Nietzsche 1966, 671-791

GM = On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), Nietzsche 1994

GS = The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche 1974

“GSt” = “The Greek State” (1871)

“GW” = “The Greek Woman” (1871), in Nietzsche 1964, 21-6

“HC” = “Homer on Competition” (1872)

HH = Human, All too Human (1878), Nietzsche 1986

KSA = Kritische Studien-Ausgabe

Nb = Unpublished Writings (1872-74), Nietzsche 1995

PP = The Pre-Platonic Philosophers (Course given 1872, 1873 and 1876), Nietzsche 2001

PTG = Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks (1873), Nietzsche 1962

TI = Twilight of the Idols (1888), in Nietzsche 1954, 463-563

UMa = David Strauss the Confessor and the Writer (1873), in Nietzsche 1983, 3-55

UMb = Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life (1874), in Nietzsche 1983, 59-123

UMc = Schopenhauer as Educator (1874), in Nietzsche 1983, 127-94

WTP = The Will to Power (1883-88), Nietzsche 1967

Z = Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-5), in Nietzsche 1954, 103-439

References

Allison, David B. (ed.). (1977). The New Nietzsche: Contemporary Styles of Interpretation. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Aristotle. (1941). The Basic Works of Aristotle. Ed. Richard McKeon. New York: Random House.

Bataille, Georges. (1991). The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Zone Books.

Bishop, Paul. (ed.). (2004). Nietzsche and Antiquity: His Reaction and Response to the Classical Tradition. Suffolk: Camden House.

Brobjer, Thomas. (2004). “Nietzsche’s Wrestling with Plato and Platonism.” In Bishop (ed.). 241-59.

Dannhauser, Werner J. (1974). Nietzsche’s View of Socrates. Ithaca: Cornell UP.

Deleuze, Gilles. (1977). “Nomad Thought.” In Allison (ed.). 142-49.

. (1983). Nietzsche and Philosophy. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson. New York: Columbia UP.

. (1990). The Logic of Sense. Trans. Mark Lester. New York: Columbia UP.

Derrida, Jacques. (1979). Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles. Trans. Barbara Harlow. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

. (1981). Dissemination. Trans. Barbara Johnson. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

Ferguson, George. (1954). Signs and Symbolism in Christian Art. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Foucault, Michel. (1973). The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. (1988). “The Drama of Zarathustra”. Trans. Thomas Helke. In Nietzsche’s New Seas. Michael Allen Gillespie and Tracy B. Strong (eds.). Chicago: U of Chicago Press. 220-231.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1977). The Phenomenology of Spirit. Trans. A.V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Heidegger, Martin. (1959). An Introduction to Metaphysics. Trans. Ralph Manheim. New Haven: Yale UP.

. (1968). What is Called Thinking?. Trans. J. Glenn Gray. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1973). The End of Philosophy. Trans. Joan Stambaugh. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1975). Early Greek Thinking. Trans. David Farrell Krell and Frank A. Capuzzi. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

. (1976). “On the Being and Conception of Phusis in Aristotle’s Physics B, 1.” Trans. Thomas J. Sheehan. Man and World. 9.3, 1976: 219-270.

. (1977a). The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Trans. William Lovitt. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1977b). Basic Writings. Ed. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1979). Nietzsche, Volume I: The Will to Power as Art. Trans. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1982). Nietzsche, Volume IV: Nihilism. Trans. Frank A. Capuzzi. Ed. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1984). Nietzsche, Volume II: The Eternal Recurrence of the Same. Trans. and Ed. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row.

. (1987). Nietzsche, Volume III: The Will to Power as Knowledge and as Metaphysics. Trans. Joan Stambaugh, David Farrell Krell, and Frank A. Capuzzi. Ed. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row.

Hunt, Lester H. (1991). Nietzsche and the Origin of Virtue. London: Routledge.

Hyde, Lewis. (1979). The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. New York: Random House.

Jeffrey, David Lyle. (ed.). (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Kluge, Friedrich. (1891). Etymological Dictionary of the German Language. Trans. John Francis Davis. London: George Bell & Sons.

Kofman, Sarah. (1991). “Nietzsche’s Socrates: ‘Who is Socrates?’.” Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal. 15: 7-29.

Lampert, Laurence. (1986). Nietzsche’s Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. New Haven: Yale UP.

. (1996). Leo Strauss and Nietzsche. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

. (2001). Nietzsche’s Task: An Interpretation of Beyond Good and Evil. New Haven: Yale UP.

Mauss, Marcel. (1954). The Gift. Trans. Ian Cunnison. Glencoe, Ill: Free Press.

Milton, John. (1993). Paradise Lost. Ed. Scott Elledge. London: W.W. Norton

More, Thomas. (1989). Utopia. Eds. George M. Logan and Robert M. Adams. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1954). The Portable Nietzsche. Ed. And Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin.

. (1962). Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks. Trans. Marianne Cowan. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing.

. (1964). Early Greek Philosophy and Other Essays. Trans. Maximilian A. Mügge. New York: Russell & Russell.

. (1966). Basic Writings. Ed. and Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Modern Library.

. (1967). The Will to Power. Ed. Walter Kaufmann. Trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale. New York: Vintage Books.

. (1974). The Gay Science. Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Random House.

. (1982). Daybreak. Trans. R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

. (1983). Untimely Meditations. Trans. R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

. (1986). Human, All too Human: A Book for Free Spirits. Trans. R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

. (1994). On the Genealogy of Morality. Ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson. Trans. Carol Diethe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

. (1995). Unpublished Writings, from the Period of Unfashionable Observations. Trans. Richard T. Gray. Stanford: Stanford UP.

. (2001). The Pre-Platonic Philosophers. Trans. Greg Whitlock. Chicago: U of Illinois Press.

Pindar. (1969). The Odes. Trans. C.M. Bowra. London: Penguin Books.

Plato. (1961). The Collected Dialogues Including the Letters. Eds. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton: Princeton UP.

. (1968). The Republic. Trans. Allan Bloom. USA : Basic Books.

. (1973). Phaedrus. Trans. Walter Hamilton. London: Penguin Books.

. (1979). Lysis. Trans. David Bolotin. London: Cornell UP.

. (1993). Symposium. Trans. Seth Benardete. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

Plutarch. (1960). The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives. Trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert. London: Penguin Books.

Reeve, C.D.C. (2011). “Plato on Friendship and Eros.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2011 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). URL = <http: //plato.standford.edu/entries/plato-friendship>.

Rosen, Stanley. (1989). “Remarks on Nietzsche’s Platonism.” In Tom Darby, Bela Egyed and Ben Jones (eds.). Nietzsche and the Rhetoric of Nihilism: Essays on Interpretation, Language and Politics. Ottawa: Carleton UP. 145-63.

Sallis, John. (1975). Being and Logos: The Way of Platonic Dialogue. Pittsburgh: Duquesne UP.

Strauss, Leo. (1952). Persecution and the Art of Writing. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

. (1964). The City and Man. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

. (1983). Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

Strong, Tracy. (1975). Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration. Berkeley: U of California Press.

Tejera, Victorino. (1987). Nietzsche and Greek Thought. Martinus Nijhoff Philosophy Library, no. 24.

Thatcher, David S. (1977). “Eagle and Serpent in Zarathustra.” Nietzsche Studien, volume 6. 240-60.

Notes

[1] We undertake this despite the fact that, for Nietzsche, Z “retains only its entirely personal meaning, being my ‘book of edification and consolation’ – otherwise, for Everyman, it is obscure and riddlesome and ridiculous” (Letter to Overbeck, July 1885).

[2] H-G Gadamer was, of course, the first to uncover this dramatic dimension of Z in his essay on “The Drama of Zarathustra.” Laurence Lampert (1986) has since extended Gadamer’s insight into a book-length analysis that focuses on how the drama impacts the overall import of Nietzsche’s teaching.

[3] On this point, Marcel Mauss is instructive: “[w]e asked why we do not examine the etymology of gift as coming from the Latin dosis, Greek δοσίς, a dose (of poison). It would suppose that High and Low German had retained a scientific word for a common event, and this is contrary to normal semantic rules. Moreover, one would have to explain the choice of the word Gift. Finally, the Latin and Greek dosis, meaning poison, shows that with the Ancients as well there was association of ideas and moral rules of the kind we are describing . . . We compare the uncertainty of the meaning of Gift with that of the Latin venenum and the Greek φίλτρόν and φαρμακον” (127).

[4] As Lampert asserts, “Zarathustra is like the sun in this dependence, for he too needs those who can receive his light” (1986, 14).

[5] For instance, at the end of the First Part Zarathustra makes the following observation concerning his disciples: “You force all things to and into yourself that they may flow back out of your well as the gifts of your love” (Z.I.22; emphasis added).

[6] Rather than speak to all, he will speak to a few – reminding us of the subtitle of Z: A Book for All and None. Having decided to move from the “all” to a “few”, Zarathustra will eventually move to the “none”; cf. D 194.

[7] This mode of discourse parallels the way in which the wise Cardinal Morton in More’s Utopia interrupts the potentially long speech of a lawyer – the modern sophist (21).

[8] We might characterize the occasions in which Socrates gives long speeches in the following manner: 1) within the context of a trial, as in the Apology; 2) out of an external inspiration, as in the Menexenus and Phaedrus; or 3) both of the above, as in the Symposium.

[9] See “Plato’s Pharmacy” in Derrida 1981, 63-171.

[10] Aristotle provides the most acute summary of this view of the relation of nature (phusis) to art (technē): “I say ‘not in virtue of a concomitant attribute’, because (for instance) a man who is a doctor might cure himself. Nevertheless it is not in so far as he is a patient that he possesses the art of medicine: it merely has happened that the same man is doctor and patient – and that is why these attributes are not always found together. So it is with all other artificial products. None of them has in itself the source of its own production. But while in some cases (for instance houses and the other products of manual labour) that principle is in something else external to the thing” (Physics II.192b 23-30); cf. Heidegger 1976, 236.

[11] Notably, in “On the Tree on the Mountainside” (Z.I.8), Zarathustra uses the image of the tree to describe a certain unity of supposedly opposite values within human existence: “But it is with man as it is with the tree. The more he aspires to the height and light, the more strongly do his roots strive earthward, downward, into the dark, the deep – into evil.”

[12] On the symbolism of the plane tree, see Ferguson, p 36. It is interesting that Milton also points to the usefulness of the fig tree with respect to providing shade on a hot day: “There oft the Indian herdsman shunning heat / Shelters in cool, and tends his pasturing herds” (IX.1108-9).

[13] The scene in Z evokes another Platonic parallel that should be noted. In the Symposium, Socrates is described by Alcibiades as a viper that bit his heart or soul, “whatever name it must have,” with his philosophic speeches (217e-18a).

[14] Cleitophon 410b; cf. Republic 332b-36a and Strauss 1964, 70. Heidegger states this more ontologically, but still emphasizes the notion that justice (Dikē) for Plato is a certain appropriateness to each thing: Dikē “names Being with reference to the essentially appropriate articulation of all beings” (1979, 166; cf. 1959, 134-35 and 1975, 41-47).

[15] Similarly, Socrates states that “if what we were just saying was correct, and a lie is really useless to gods and useful to human beings as a form of remedy (pharmakon), it’s plain that anything of the sort must be assigned to doctors while private men must not put their hands to it … Then, it’s appropriate for the rulers, if for anyone at all, to lie for the benefit of the city” (389b; cf. on the “noble lie” 414b-15d).

[16] I would agree with Lampert that this mode of communication is selective, culling out those worthy to be disciples, and within Nietzsche’s writings more broadly, those capable of facing Nietzsche’s ultimately “deadly truths”. However, I do not think we can say, as Lampert asserts, that Zarathustra, at this point at least, tries to “speak differently to different people” (1986, 45). One is reminded of Nietzsche’s warning with respect to the philosopher’s possibility of becoming a “volcanic menace”: “From time to time they revenge themselves for their enforced concealment and compelled restraint. They emerge from their cave wearing a terrifying aspect; their words and deeds are then explosions and it is possible for them to perish by their own hand” (UMc 3).

[17] Strauss 1964, 52; cf. Derrida 1981, 163-71; and Sallis 161-66. Interestingly, we may also assume that Nietzsche felt that his writings passed the qualifications put on that mode of discourse by Zarathustra in “On Reading and Writing” (Z.I.7).

[18] Notably, during a period in which the Jewish people were being plagued by serpents, the Lord said to Moses: “Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live” (Numbers 21.6-9).