Review of Mad Men: The Death and Redemption of American Democracy

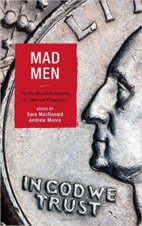

Mad Men: The Death and Redemption of American Democracy. Sara MacDonald and Andrew Moore. Lexington Books, 2016.

It’s been a decade since Mad Men premiered on television, with its alluring and disturbing portrait of America in the 1960s. This prestige drama and its mysterious protagonist, Don Draper, captured viewers’ imaginations for seven seasons, portraying a pivotal era of modernity. Critics and fans continue to discover and revisit the show. Its lush visual beauty allows us to revel in the glamour of mid-century modern aesthetics, while its psychological portraits and layered symbolism reward repeated viewing. Just as Don Draper leads a double life, Mad Men’s focus on the ambitious, beautiful, upper-middle-class Manhattanites of the postwar period offers two simultaneously contradictory experiences. There is nostalgic pleasure in its Camelot-era style and excess; but as that illusion is also stripped away, exposing its dark and lonely underbelly, it also rewards a postmodern sense of irony and historical foreboding. The series has claimed an important place in the television canon, not just for its sophisticated storytelling and nuanced characters, but for the way it illuminates a compelling moment in American cultural history by linking those personal stories to larger political themes, both demonstrating and interrogating our notions of freedom and progress. Thus it is perfectly fitting that a new collection of essays, Mad Men: The Death and Redemption of American Democracy (Lexington, 2016), takes up these political questions. Editors Sara MacDonald and Andrew Moore have assembled a provocative and intriguing set of authors who situate the show as an important political text, with something to tell both scholars and fans about the evolution of the American ideals and idealism.

Mad Men: The Death and Redemption of American Democracy contains eight chapters, organized around four central themes: Freedom & Happiness, the American Dream, Equality & Opportunity (particularly for women and racial minorities), and Redemption & Forgiveness. The overarching argument of the book is that, as we look back at the series as a whole, we should see not only the dark side of American modernity (played out primarily in Don’s downward spiral); if we look more closely, we can also find seeds of hope and, as the subtitle indicates, redemption of American democratic ideals. This determinedly optimistic reading of the show distinguishes this collection from many other scholarly examinations. In addition, the editors are both professors in the Great Books program at St. Thomas University, and their skill and familiarity with analyzing texts is well demonstrated here. The television series is, appropriately, treated with the care and attention that one might bring to a classic work of literature or philosophy. These authors do both Mad Men and their readers a great favor by showing how to do this kind of interdisciplinary work and to take popular culture seriously. By reading specific characters and plot points as symbols of larger historical and political themes, this book makes the personal political, and represents the Madison Avenue exploits of this handful of characters as indicators of the larger social, political and cultural forces at work in the United States in the modern period.

Each chapter works by reading the show through the lens of another political philosopher or work of literature. For example, Sara MacDonald re-interprets Don Draper’s odyssey as Dante’s journey through the Inferno toward ultimate redemption. Andrew Moore reads the problematic relationship of Don Draper with his past, and his insistence that one can always run away and reinvent oneself (a classic American trope, explored by my colleague Lilly Goren in her excellent chapter on grifters in American literature in Mad Men and Politics: Nostalgia and the Remaking of Modern America) against Hannah Arendt’s grappling with the problem of history and forgiveness. Matthew Dinan’s interesting analysis of American dreams examines the show in light of Plato’s debate between poetry and philosophy in the Republic. He enlivens the classic argument over the roles of reason and affect in good citizenship, and the dangerous creation of desire via poetry forward into contemporary terms, by discussing advertising as akin to poetry. He argues that Mad Men shows desire playing a positive role in creating a more just and inclusive polis, unlike Plato. Barry Craig and T. D. Anderson take up the liberal notion of freedom in light of Hegel and Isaiah Berlin, respectively. As they position Don Draper as one seeking freedom and happiness through total autonomy, they are drawn to the conclusion that unfettered autonomy does not lead to Don Draper (or the United States, by implication) to feel fulfilled or free. Both end up tempering the notions of Hegel and Berlin to reconcile an individual’s relationships and commitments with unlimited autonomy as the way to live the most free and good life, as they conclude Don Draper does at very end of the series by reconciling with his daughter, saying a kind farewell to his dying ex-wife, and apparently returning to his employer to write a wildly successful Coke ad.

If I have any questions about this volume, it is to wonder why it is so committed to this reading of the show as ultimately optimistic – or perhaps why it insists on the binary of the subtitle, the stark choice between death or redemption. Mad Men is a complex, multi-faceted text. Its depth and relevance come from avoiding simple dichotomies and heavy-handed moral conclusions. The chapters in this book are conceived with such creativity and attention to textual detail, there are times that its assertion that “American liberalism might be the political model [through which]. . . the modern political project might succeed” seems abrupt and not wholly justified. As David Snow notes in his chapter on gender and sexual orientation, liberal notions of autonomy are inadequate to explain or to remedy systemic sexism. Postmodern concepts of intersectionality, or irony, or situated discourse (rather than liberal notions of universal truth or abstract ideals) provide more helpful ways of interpreting Mad Men and the nostalgia it evokes, with its attraction and revulsion at the rise of modern America – an emerging superpower, but with costs of wartime destruction and loss of political innocence; filled with rising economic opportunity, but with great inequalities; the American dream that may also be a Revolutionary Road nightmare. From the opening chapter featuring Hegel, to the concluding one focused on Arendt, the authors’ reading of Don Draper, Peggy Olson, Joan Harris Holloway and the rest repeatedly turn not to liberal democracy – but to various notions of republicanism, communitarianism, feminism, and postmodernism that point to the value of individual human life within a web of relationships, obligations and communities, to love and forgiveness over pride and autonomy. There is an implicit critique of the limits of liberalism in the lenses through which the show is read, and the textual interpretations offered. The “redemption” of the title is not triumphalist, and I suspect it is not uniquely or solely liberal.

The editors are right when they claim that this show tells us something not only about our past, but about our present. Our nostalgia for elements of the 1960s, and the eerie familiarity of some of those past dilemmas (such as racial injustices and the ways in which they are invisible to white privilege), demonstrate that this is not just a text about an era of modernity 50 years ago. It is a text that offers us an opportunity to reflect on and engage those issues and ideas today. It is a welcome perspective that American and modern politics, like Don Draper, may not be utterly doomed. But that hopefulness for change and renewed possibility is, like Don’s at the end of the series, chastened with experience, loss, human finitude and the need for connection. This volume will not only be of interest to fans of Mad Men and to scholars looking for ways to do this sort of interdisciplinary textual analysis, but it is also likely to provide those of us who teach political theory with a way to engage our students, via popular culture, with some of the enduring themes and classic dilemmas of our tradition. It is a welcome and intriguing addition to the scholarly canon of work on Matthew Weiner’s deserving and fascinating television series.

An excerpt of the book is available here.