A Book About Nothing?

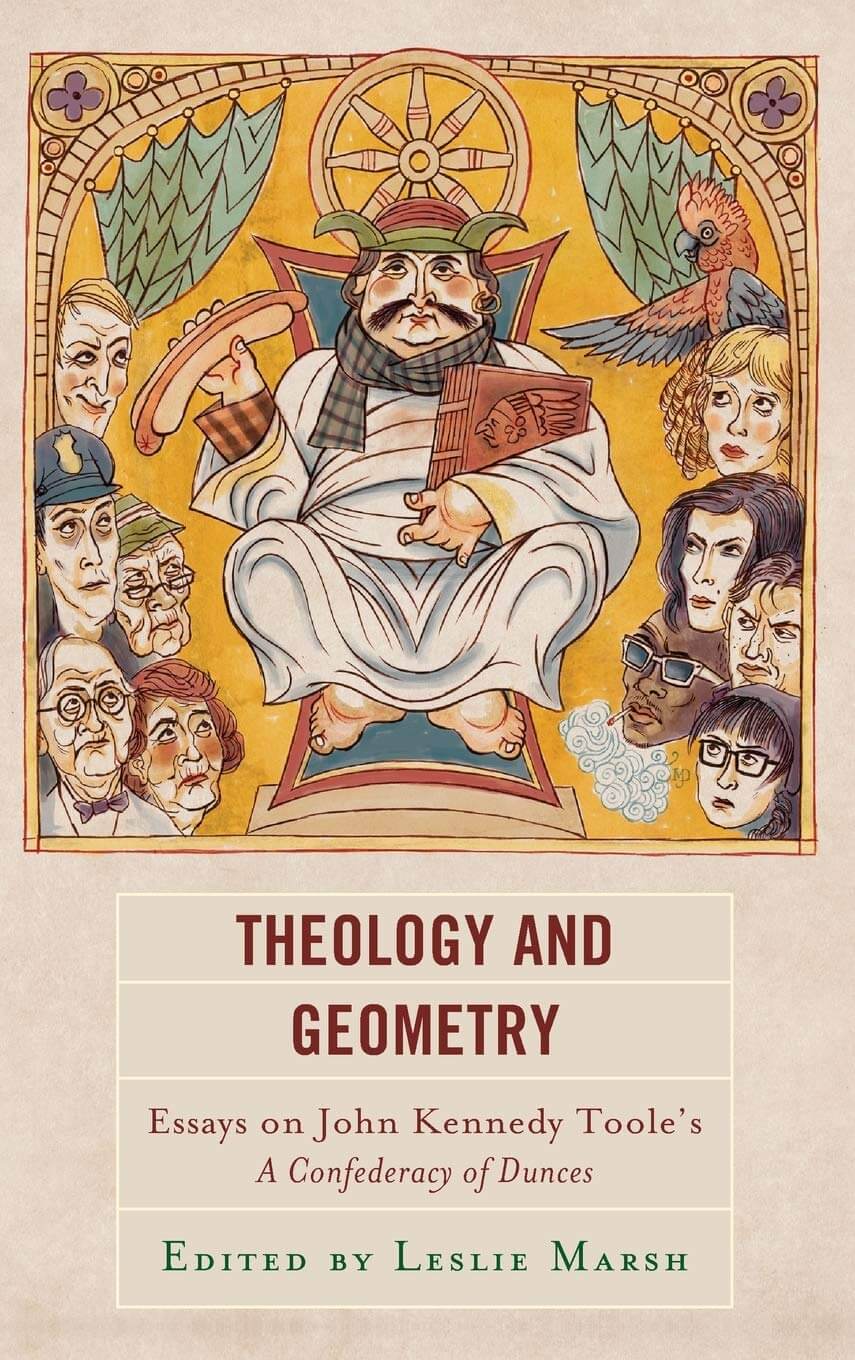

Theology and Geometry: Essays on John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. Leslie Marsh, ed. Lexington Books, Lanham MD, 2020.

Theology and Geometry is a book about a book, in this case a collection of essays about A Confederacy of Dunce, a comic novel published posthumously in 1980. A few things should be said about Confederacy as an introduction to the book under review.

Confederacy was written in the mid-1960s by John Kennedy Toole, known as Ken or Kenny to family and friends. Born in New Orleans in 1937, he grew up there, becoming intimately familiar with its subcultures and personages. Described by a friend as both “extroverted and private,” Ken used his gift of mimicry to become a center of attention and interest at parties. Such a gift exemplified his ability to observe and remember details that were incorporated into the characters in Confederacy.[1]

Set in ca. 1962 New Orleans, A Confederacy of Dunces chronicles a few months in the life of Ignatius J. Reilly, a haughty and obese 30-year-old living at home with his mother. Despite Ignatius’s rough exterior, his frequent allusions to medieval philosophy most notably Boethius and his Consolation of Philosophy, leads one to think that inside there is philosophical and moral depth. However, this was not the case. Petulant and resistant to work, when asked whether he had a job (he did not), Ignatius replied indignantly: “I dust a bit … In addition, I am at the moment writing a lengthy indictment against our century” (Confederacy, 6).[2]

In the opening chapter after having consumed a few beers, Ignatius’s mother backs her car into support posts along St. Anne Street in the French Quarter bringing an overhead balcony crashing down. Fearing that the ensuing financial costs would result in the loss of her home, Mrs. Reilly forces the disdainful Ignatius out of the house and into the job market and the world at large, an action that triggers the complex series of events that constitutes the balance of the novel. Despite the frequent allusions to Boethius, a contributor to the volume at hand noted that Ignatius “seems more fitting as a humorous character from The Canterbury Tales or a Dickens novel than a disciple of Boethian thought.”[3]

The phrase “theology and geometry”—used as the title of the book under review—was a favorite phrase of Ignatius used as the metric by which the modern world is judged deficient. For example, at the beginning of the novel Ignatius was watching a crowd “for signs of bad taste in dress” and noticed that several outfits were “new enough and expensive enough to be properly considered offenses against taste and decency.” For Ignatius “possession of anything new or expensive only reflected a person’s lack of theology and geometry” (Confederacy, 1).

The phrase was the invention of Toole’s friend and colleague, Robert Anthony “Bobby” Byrne (1928-2000),[4] a native of New Orleans who found an academic career at what was then known as the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) where he taught along with Toole in the mid-1960s. Byrne was in many ways the inspiration for Ignatius in terms of his size, his garish dress, and his knowledge of medieval philosophy and theology—additionally, he often talked about Boethius. In contrast, Byrne was not known for the peevish and self-indulgent qualities of Ignatius. Byrne told an interviewer that Toole had probably never read the Consolation of Philosophy and what he did know about it, he had picked up from Byrne.[5] However, Toole’s biographer indicated that he already had at least a rudimentary knowledge of Boethius prior to meeting Byrne.[6]

Toole made several attempts to have his manuscript published. Submitting it to Simon and Schuster initiated a long correspondence with one of its editors Robert Gottlieb who became Toole’s primary foil with Gottlieb ultimately rejecting Confederacy having suggested that it had no point which Toole understood to mean that it had no universal significance. Close to despair he wrote that “The book seemed to become about nothing.”[7]

After several fruitless attempts to publish the novel, Toole committed suicide in March 1969 along a lonely stretch of Popp’s Ferry Road in Biloxi, Mississippi. That might have been the end to the book, if his mother Thelma Toole—who would have fit nicely among the novel’s characters—had not set out on a course to see that her son’s work was published, a campaign that eventually led her to Walker Percy in 1976.

Although renowned as a novelist, Percy is often regarded as more a philosopher than novelist often focusing on matters pertaining to the limitations of the scientific method in human life and to the symbolic dimension of human existence. After marrying in 1946, he had settled first in New Orleans and then in 1948 moved across Lake Pontchartrain to Covington. In 1961 he published his first novel The Moviegoer which won the National Book Award for fiction. Although Percy and Toole never met, although Toole was probably familiar with Percy’s work.

After reluctantly agreeing to read the manuscript, Percy found that he was irresistibly drawn into its madcap narrative terming Ignatius Reilly “a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.” In the Foreword to the published edition, Percy hesitated to “use the word comedy—though comedy it is—because that implies simply a funny book, and this novel is a great deal more than that. A great rumbling farce of Falstaffian dimensions would better describe it; commedia would be closer to it.” (Confederacy, vi-vii). Partially through Percy’s enthusiastic support, Confederacy was published in 1980, and the following year it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

* * *

I first encountered Confederacy in the late 1980s when a friend gave me a worn paperbound copy; I immediately found it riveting. I couldn’t put it down. A few years later the television series Seinfeld began its nine-season run with each episode. Its quirky comedy focused on trivial events that intertwined Rube Goldberg-like until arriving at often unexpected resolutions. The series indirectly described itself as being a show “about nothing,” suggesting that in its focus on minutiae however hilarious there was no greater meaning to be found.

With its references to medieval philosophers and saints, Confederacy comes across as a paradox, on one hand appearing as a manic comedy wile on the other quietly beckoning the reader to see a deeper meaning. The novel’s title is evocative deriving from Jonathan Swift: “When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.”[8] One can easily imagine the cast of characters and their antics as being the confederacy of dunces alluded to, but what “true genius” were they in confederacy against? The first thought is that it alludes to Ignatius, the “perverse Thomas Aquinas,” however, his character and his actions suggest otherwise.

The book at hand was edited by Leslie Marsh who recently edited a volume of papers entitled Walker Percy, Philosopher (2018). In the preface, Marsh noted that “[h]owever one comes to John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces all roads lead to Walker Percy.” With the clue to its significance lying “obliquely with Percy himself” (page xi).

The book consists of eleven essays by eleven authors (including the editor) and a preface by the editor. The eleven “do not stringently conform to an a priori editorial expectation that certain aspects of the novel must be tackled.” Each contributor was asked to write “solely on that aspect which motivated them” (page xi). Consequently, a wide variety of topics are touched on.

One chapter is a memoir of Ken Toole’s mother, Thelma, a true New Orleans eccentric, accompanied by photographs of her, all by Christopher R. Harris. Another essay by H. Vernon Leighton deals with the nature of humor and its manifestation in Confederacy. A third by Connie Eble, examines Toole’s rendering of New Orleans dialects and concludes that “[g]ood dialect writing evokes in readers a culturally rich impression of authentic speech” and Confederacy succeeds in this arena (page 167).

However, several essays champion the insight that behind the paradoxical façade of the novel lurks a quiet wisdom. In his contribution “‘Amusingness Forced to Figure Itself Out’: Ignatius J. Reilly, Aesthetic Individualism, and the Modernism of Anti-Modernism,” Kenneth B. McIntyre addresses the problem of whether Ignatius was, a follower of medieval philosophy who stood in opposition to the modern world, or something else. He determines that Ignatius is better understood under the rubric of the Kierkegaardian aesthete, someone “primarily concerned with the world in terms of its pleasantness, its capacity to entertain, and/or its capacity to excite wonder or awe, and not in terms of its moral goodness” (page 43). He makes a convincing case through comparing Ignatius to Percy’s protagonist Binx Bolling in The Moviegoer, who is clearly portrayed as a Kierkegaardian aesthete in part through the use of an epigraph from the Danish philosopher. This is made all the more convincing because Ignatius like Binx was an almost daily attendee of the New Orleans cinemas.

In “Theology and Geometry and Taste and Decency,” volume editor Leslie Marsh contributes an essay that examines “the two leitmotifs” of Confederacy one of which is incorporated into the title of the volume under consideration. The first of the two—theology and geometry—connotes the sacred, while the second—taste and decency—connotes the profane (page 61). Paralleling them, Boethius’s Consolation invokes the sacred, while New Orleans the profane. Confederacy is a “satirical mediational on an uncritical doctrine of progress” and a “scathing critique of the more philistine manifestations of (an acquisitive) American culture and the smorgasbord of secular religions that vainly try to fill the void of a long-lost sanctity” (page 62). With its New Orleans setting much of which is in the French Quarter, a “byword for decadence,” correlations with the profane are not difficult to see. In contrast to the decadence of New Orleans, Boethius provides a gleam of transcendence in harking back to “the authority and certainty that are attainable only through stable institutions and inherited traditions of law and serious citizenship” (page 69). In the contrasting images of the sacred and the profane, Toole evoked “a spiritual wholeness and social cohesion that was vanishing from the world of industrial capitalism” (page 70).

In “The Consolation of Dunces,” Stephen Utz rhetorically asks whether despite Confederacy’s comedic veneer, it can then “have philosophical content as well?” Walker Percy’s advocacy for the book suggests that there is more to it than meets the eye; its surface “overlies a background commentary on the problem of moral luck that Boethius grasped and attempted to solve” (page 79). According to Utz, Toole introduced Boethius to indicate that his project was both literary and philosophical involving a commentary upon the philosopher who argued in Consolation of Philosophy against the correlation of virtuous conduct and worldly reward. Toole appears to suggest that “the irrationality of life” is “like a playground’s rides. One can fall off them and then get back on” (page 87).

In “Ignatius Reilly as the Knight of Faith,” W. Kenneth Holditch asserts that Confederacy is “a philosophical and even a religious [novel]” (page 93). Pointing out that medieval philosophy isn’t the only Christian influence on Ignatius, there were also Toole’s contemporaries Walker Percy and Flannery O’Connor, both noted for their Catholic backgrounds, and who were both influences on Toole. All three were influenced by Kierkegaard a founder of Christian Existentialism for whom the absurdity of faith meant that a believer would be considered absurd in an absurd world. For the Danish philosopher, anyone who takes the leap of faith in God becomes a Knight of Faith. The outlandish predicaments and the ensuing response of Ignatius Reilly find a parallel in the Knight amidst the absurdity of a confederacy of dunces.

Like a multi-faceted jewel, A Confederacy of Dunces refracts light at multiple angles, beckoning the reader to peer beneath its surface. And certainly, much is to be found within its enthralling pages. Those who look might find in the glimmering a suggestion of something more, and Theology and Geometry will certainly help the reader to see it.

Notes

[1] Carmine D. Palumbo, “John Kennedy Toole and His Confederacy of Dunces,” Louisiana Folklore Miscellany, vol. 10 (1995), 64.

[2] References to A Confederacy of Dunces are to the edition published by Louisiana State University Press in 1980.

[3] Anthony G. Cirilla, “Ignatius J. Reilly’s Menippean Misreadings and Onanistic Annotations of Boethian Philosophy,” 142.

[4] In an interview, Byrne noted that he had borrowed the “geometry” component of the phrase from the horror writer H.P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928), where it referred to someone having a distorted perception of space. By adding “theology,” Byrne created a phrase that was used to describe those “whose life and view of the world was all crooked.” Palumbo, “John Kennedy Toole and His Confederacy of Dunces, 65.

[5] Palumbo, “John Kennedy Toole and His Confederacy of Dunces,” 63, 67.

[6] Cory MacLauchlin, Butterfly in the Typewriter: The Tragic life of John Kennedy Toole and the Remarkable Story of A Confederacy of Dunces (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2012), 50.

[7] MacLauchlin, Butterfly in the Typewriter, 180.

[8] Jonathan Swift, Thoughts on Various Subjects, Moral and Diverting (1703).