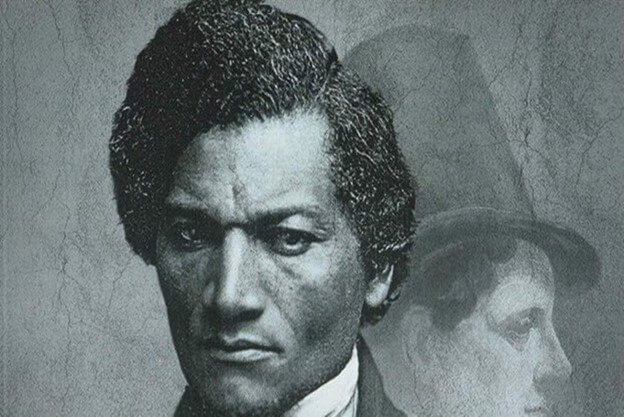

A Narrative of Fraternity for our Times: How American abolitionist Frederick Douglass connected with an Irish Politician

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass witnessed the beginnings of the Irish famine horrors firsthand. He arrived in Ireland in 1845, at the invitation of the Hibernian Anti-Slavery Society, the leading such group in Europe at the time.

But to put it simply, he was there because he was a “wanted man” in his own country. His Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave had just been published in America. He was a fugitive, and his “owners” wanted his capture. Such was the popularity of Douglass’ book that a new version was published in 1846 while he was visiting Britain and Ireland. It is called the second Dublin edition, and in the new preface Douglass said he felt totally free to name his oppressors.

He believed that his book would help “tens of thousands” of people cooperate in the “overthrow of the meanest, hugest, and most dastardly system of inequity that ever disgraced any country.”

Douglass meets Daniel O’Connell

Nonetheless, the highlight of his visit to Ireland must have been meeting and hearing the “Liberator,” the renowned Daniel O’Connell. O’Connell achieved Catholic Emancipation in 1829, which for the first time gave Catholics the right to vote, sit in parliament and freely participate in public life.

Douglass and O’Connell’s lives intersected, unfurling a new narrative on “fraternity” for the peoples of North America and Ireland. Douglass explains in his Narrative how at the age of 12 he read a book called The Colombian Orator. In it he came across speeches about Catholic Emancipation. He repeatedly read the talks.

He describes how they “gave tongue to interesting thoughts in my own soul … The silver trump of freedom had aroused my soul to eternal wakefulness … It was ever present to torment me with a sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it, I heard nothing without hearing it, and felt nothing without feeling it.”

Douglass discovered in the power of the words of people like Daniel O’Connell the beauty and worth of his own being. Such language was different from the “valuation” he had encountered in the plantations and slave markets. He describes how there, “we were all ranked together at the valuation. Men and women, old and young, married and single were ranked with horses, sheep and swine … and all were subjected to the same narrow examination.”

Recently, Pope Francis decried this devaluation of human beings in his encyclical on fraternity, Fratelli Tutti, remarking how “whether by coercion, or deception, or by physical or psychological duress, human persons created in the image and likeness of God are deprived of their freedom, sold and reduced to being the property of others. They are treated as means to an end.”

Human misery in Ireland

On his arrival in Ireland, Douglass saw “painful exhibitions of human misery” everywhere. While in Dublin, he visited cabins or huts near the city. He was completely shocked by what he saw. He wrote how “of all places to witness human misery, ignorance, degradation, filth and wretchedness, an Irish hut is pre-eminent … Men and women, married and single, lie down together, in much the same degradation as the American slaves.”

Douglass clearly identified with the Irish. He commented that those who think themselves abolitionist and “yet cannot enter into the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true foundation for his anti-slavery faith. The responsibility to end slavery belonged to Americans as well as the Irish, but because they [were] MEN.”

He felt all the Irish lacked was “black skin and wooly hair, to complete their likeness” to the plantation slave. Douglas pointed out that “slavery was not what took away one right or property in man: it took [away] man himself.”

The Liberator’s sympathy unlimited

Douglass was deeply impressed by the eloquence with which O’Connell spoke in Conciliation Hall, Dublin. The Liberator devoted a large part of his speech to “the plague spot of slavery” in North America. In his own speech O’Connell said, “my sympathy is not confined to the narrow limits of my own green Ireland.”

He declared “my heart walks abroad” and “wherever the miserable is to be succored, and the slave is to be set free, there my spirit is at home.”

Douglass relates a story about O’Connell’s meeting with an American gentleman. The gentleman offered his hand to greet the Liberator, but O’Connell withdrew his, asking if the American was a slaveowner.

“No,” the man replied, “but I am willing to discuss the question of slavery with you.”’

“Without meaning you the least harm in the world,” O’Connell said, “should a gentleman come into my study and propose to discuss with me the rightfulness of picking pockets, I would show him the door, lest he should be tempted to put his theory into practice.”

O’Connell never forgot to communicate the human face of slavery. He moved his audiences to tears with his descriptions. On one occasion he described the slave mother who “looks upon the child she has borne and knows that she is but rearing the slave of another.”

Key experiences for Douglass

In his letters and speeches in his My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass continually refers to how throughout life, his associations with the Irish functioned as a crucial component to his own liberation.

On his ship voyage to Britain and Ireland, he tells of how with most passengers “all color distinctions were flung to the winds, and I found myself treated with every mark of respect, from the beginning to the end of the voyage, except in a single instance.”

Douglass was invited to give a lecture on slavery to the passengers, but those from New Orleans and Georgia took offence and threatened to throw him overboard. But the captain and other passengers intervened. Captain Judkins threatened to put those aristocratic men in chains, and at that, they scampered away.

Reaching Liverpool, the pro-slavery Americans went to the press “to justify their conduct” and to denounce Douglass as being “worthless and insolent.” But it backfired on them because it simply secured Douglass a greater audience.

Douglass was only a few days in Dublin “when a gentleman of great respectability” offered to show him around. He even found himself dining with the Lord Mayor of Dublin. Frederick explains how the people he met “measure and esteem [people] … according to their moral and intellectual worth, and not according to the color of their skin.”

Douglass visited not only Ireland but also England, Scotland and Wales, and it is, he says, to “these friends I owe my freedom.” Douglass finds it important to point out that neither in speech nor writings does he ever allow himself to be simply against Americans. He says he takes his stand “on the high ground of human brotherhood … Slavery is a crime … against God, and all members of the human family; and it belongs to the whole human family to seek its suppression.”

“The chattel becomes a man”

In one of a series of letters addressed to William Lloyd Garrison, an American abolitionist, Douglass speaks directly about his homeland and Ireland. He tells of how “the land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave … so that I am an outcast from the society of my childhood, and an outlaw in the land of my birth.”

“In Ireland,” he says, “I was not treated as a color, but as a man — not as a thing, but as a child of the common Father of us all.” Traveling throughout that land, Douglass said: “I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation.

“I live a new life … Instead of the bright blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! The chattel becomes a man.”

A narrative for our times

The “new life” Douglass speaks of, and experiences is that of “fraternity.” Brotherhood is not an abstract definition for him, but about “becoming who we are as human persons.” It is an existential reality and therefore touchable.

Douglass describes the elements of this reality as encountering “glorious enthusiasm,” “deep sympathy,” “cordiality,” “kind hospitality” and a “spirit of freedom.”

The O’Connell-Douglass narrative on fraternity is a message for our times in America, Ireland and the world at large. It entails an enlarging of the human heart to the reality of who our neighbor is.

We cannot just sit back, asking, “what have we to do with slavery?”

As the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn said, the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. During the life of any human being this line keeps changing places.

So, it is up to us to write the account of who we truly are as human beings, that is, a narrative for our times.

Published originally in Living City (Hyde Park, NY), August/September 2021, Volume 60. No. 8-9.