Best of Times, Worst of Times

We’re living through what are – like all times – the best and worst of times. As our calendar enters the new year, we can’t help asking ourselves how it is with us and with our world. I’m no different, so I’ll share my Q & A with you.

It seems to me that I’m continuing to live my own life-adventure, or story. But is “my story” a true one or am I just making it up? How can I know? I think I know, but can I trust my experience?

Let’s take the doubt seriously. Not every era would have encouraged such a doubt – not the way our time does. Where did it come from, the doubt? It’s a question that can be answered in many ways, but I tend to look to philosophy for light on where we get our prevailing opinions.

To probe the question, it’s still useful to divide philosophic work into two main types: analytic and continental.

I’ll start with the analysts. They tend to suppose that objective truth lies with the natural sciences. Early on, they assigned to philosophy the task of connecting human experience with scientific accounts of the world of fact – the world outside us. For reasons trackable to the 17th-century, they treated experience as if it were cut into bits called sense data. However, once experience is cut up like that, they were never going to get to the world of atoms and electrons described by physicists. Or the world of past reports described by historians. Or, for that matter, people in real-life conversations, saying “What an awkward pause that was!” So those attempts failed to go from experience to the sciences, and they failed even to account for how we ordinarily talk about experience.

Recovering from earlier frustrated hopes, many analysts turned to clarifying how we actually talk, and the assumptions that stand behind what we say. That kind of work still leaves the open gap between human norms and an outside world of objective fact – a world indifferent to our norms.

Did our norms rest on any foundations beyond mere convention? I once put that question to Australian philosopher David Stove. Promptly and wittily, he told me: “Yes, but no gentleman would ask you what they are!”

Meanwhile, on the continent, I think Sartre was the first to claim that we can make ourselves up however we choose. He argued that Freud’s account of the unconscious was false because the patient’s ability to dodge the psychoanalyst’s probes shows his awareness of what he’s trying to hide. So far so good, but Sartre drew the further inference that we are entirely self-transparent, nothing is unconscious, the psyche has no natural structures and is thus free to make and remake itself at every instant. All of which did not follow from Sartre’s argument against Freud.

Michel Foucault and Antonio Gramsci gave further support to the wider claim that there is no objective truth, only contending ”narratives” and that the latter are really about power struggles.

Foucault wrote two books reviewing the history of insanity and its treatment (Madness and Civilization, 1960 and Birth of the Clinic, 1963). There he argued that people confined as mad were classified for the purpose of exerting the power of society and its norms over those who did not conform. The diagnosis of insanity was an assertion of the diagnostician’s power.

For analogous reasons, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks (1929-35) discounted criticism from disciplines like economics and political science since, he held, such criticism was effectively an exercise of power, serving the interests of the establishment that revolutionaries like him were morally bound to overthrow.

A moment for evaluation: Let’s compare Foucault on madness to Phyllis Chesler’s Women and Madness (1972). Chesler used her training as a psychologist to expose the confinement of women to asylums by tyrannical husbands and their exploitation– sexually and as housemaids – by tyrannical psychiatrists. She was able to effect reforms in her profession. But she did not suggest that there was no such thing as insanity or that only power disparities were involved. From the fact of abuse of power, that inference did not follow.

As for Gramsci: he and his fellow revolutionaries were following directives from a Soviet regime now thought responsible for tens of millions of deaths – as well as the coarsening of art, language, and the environment. So Gramsci was mistaken about where his moral obligation lay. The truth-seeking disciplines he discounted might have helped him to find that out and make a better use of his talents.

In sum: the intellectual supports for the view that we and our environment are constructs – things made up – turn out fairly flimsy!

Meanwhile, new scientific disciplines are finally coming to the support of ordinary human experience. Currently, the disciplines of “computational perceptual psychology” and “ecological psychology” are minutely tracking what actually happens in human perceptual experience. They are finding that we perceive external reality directly, not via inferences from sense data. We see the world. We take in the world. And our perception is closely bound up with intellectual processes as well as with our purposive acts in the world. There’s a world out there. We encounter it in the round. We are entitled to trust our experience with its powers to act and self-correct. What they are finding is quietly momentous.

On the subject of better times ahead, I’ve written previously about the growing body of empirical evidence that we do survive physical death. Among experiences typically reported by those who come back from clinical death is “the life review.” When we review our lives after we die, we will actually feel the harms we’ve inflicted on others – feel them as they felt them. Alas, the life review is unlikely to be unvarnished fun.

That said, I can’t help looking forward to the life review in store for the latest brand of bully, the Woke bully. The Woke bully can get a Chinese professor fired for innocently using a term in Chinese that happens to have the same sound as a bigoted epithet in English. For the Wokester, everything’s about power; intentions don’t count. What I want to imagine, as empathically as I can, is that Wokerster perp directly experiencing the suffering he inflicted on an innocent prof. What’s that going to be like?

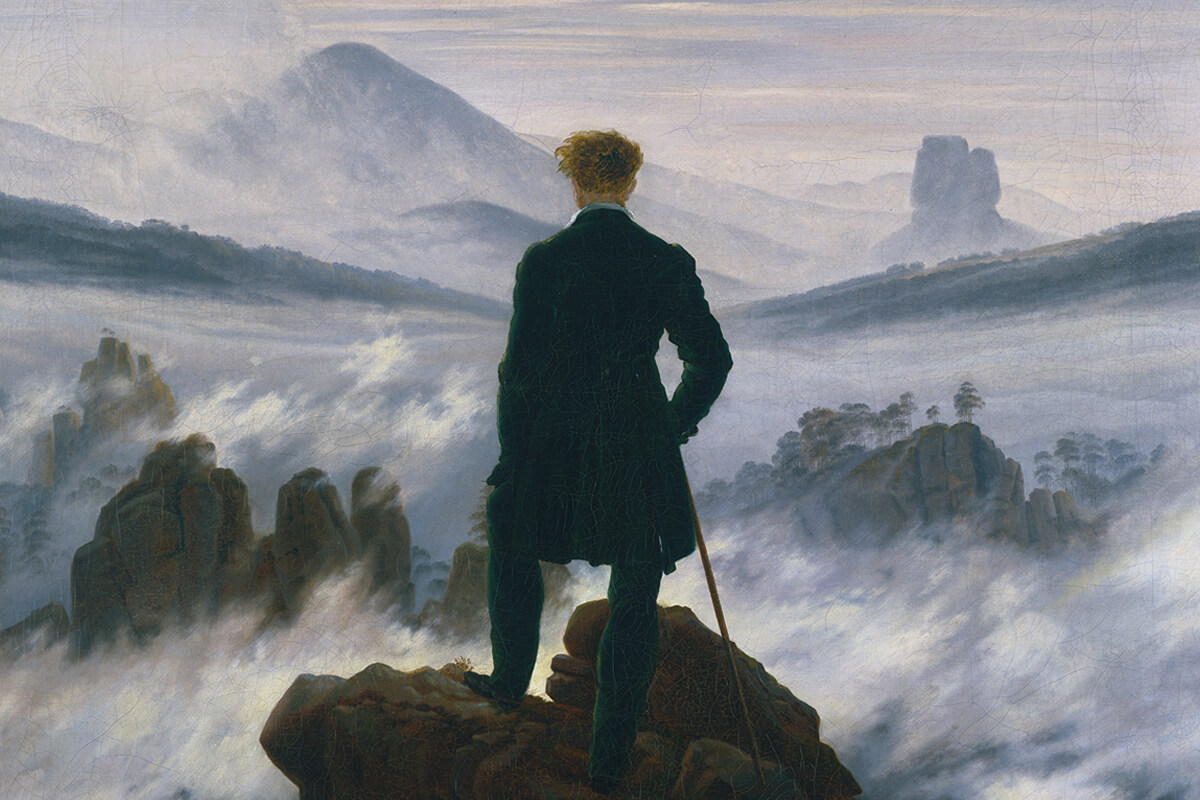

Why it’ll be positively redemptive! For the weary, wayward, wandering Wokester – all at sea as he is — it’ll be Land ho! The Woke perp will find that there’s a moral reality out there! He’ll make the great discovery:

I’m not alone. I’ve not been set adrift to make up … everything! I’m a member of a living human community!

For that sad perp, it’ll be the equivalent of a resurrection!