Books Matter: A Review of “The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest”

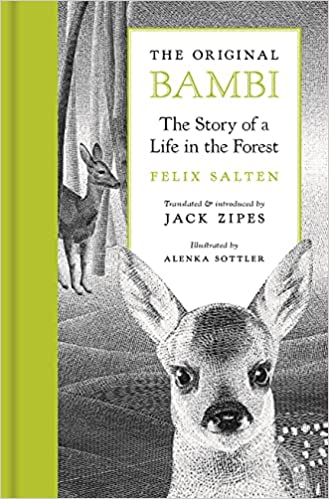

Felix Salten, The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest. Translated & Introduced by Jack Zipes, Illustrated by Alenka Sottler. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022.