Caught Between East and West: Solzhenitsyn’s American Exile

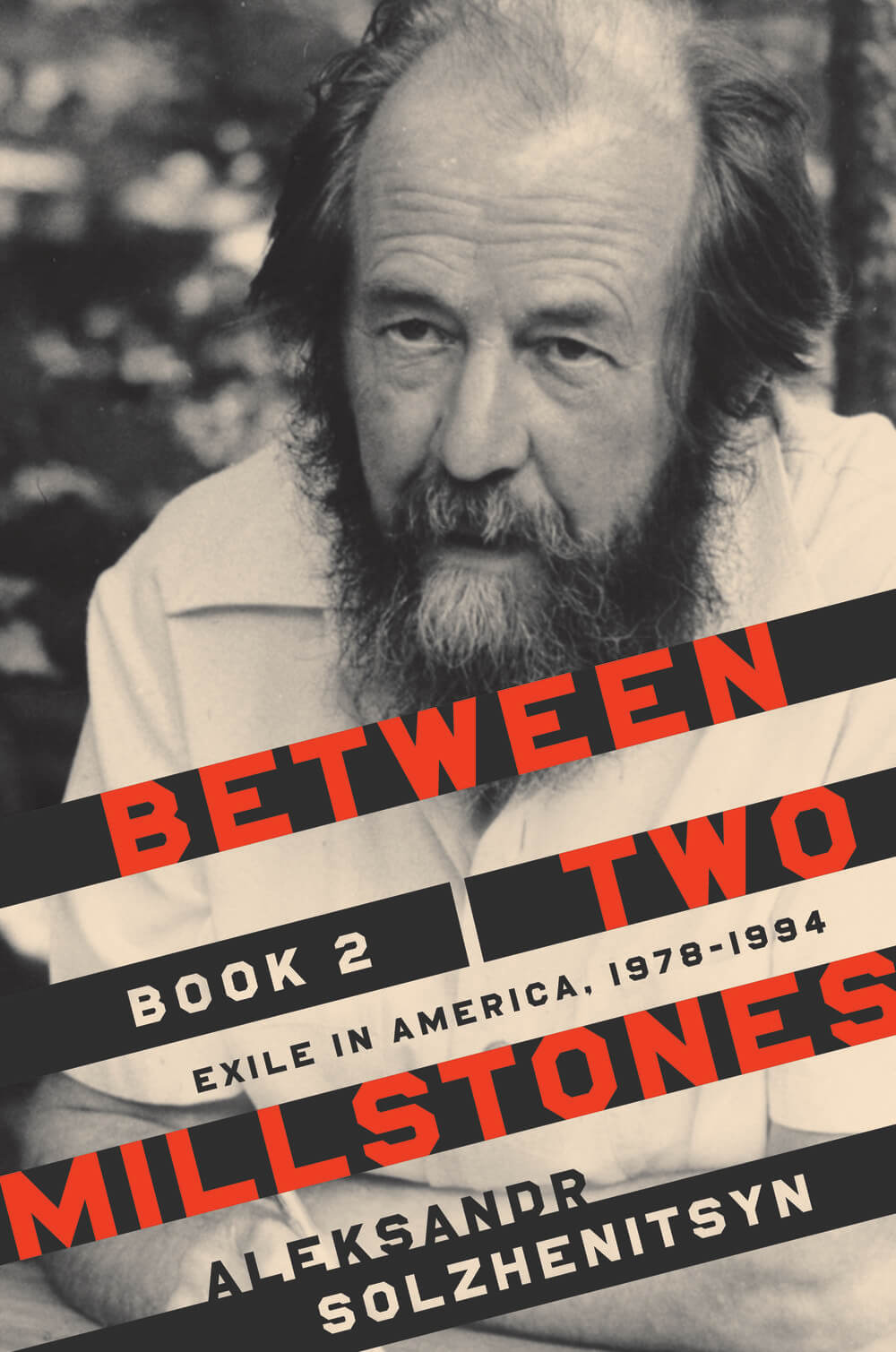

Lee Trepanier’s interview with Daniel J. Mahoney, Solzhenitsyn scholar and author of the “Foreword” to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Between Two Millstones: Book 2: Exile in America, 1978-1994, translated by Clare Kitson and Melanie Moore. The book was published by the University of Notre Dame Press in October 2020.

Why is the book called “Between Two Millstones?”

The full title of the work is The Little Grain Fell Between Two Millstones (Ugodilo zyornsyhko promezh dvuk zhernovov in the original Russian). This second book covers the years from 1978 to 1994, from just after Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address (delivered on June 8, 1978) until his return to post-Communist Russia in May 1994. Like the preceding volume (which begins with Solzhenitsyn’s forcible exile to the West on February 13, 1974) BTM-2, as I shall call it, traces Solzhenitsyn’s continuing battle with the totalitarian state he did not hesitate to call the Soviet “Dragon,” as well as the ongoing hostility of Western elites who seemed to hem him in at every opportunity. Still pursued by Soviet intelligence services, and the victim of a massive propaganda campaign of vilification, Solzhenitsyn also faced a western media, especially in the United States, that distorted almost everything he had to say. This advocate of “repentance and self-limitation,” and the “democracy of small spaces,” was habitually confused with an authoritarian and extreme nationalist. The same misrepresentations were recycled by journalists, politicians, and academics with impunity. No one ever gave any quotes, as Solzhenitsyn told the Time journalist David Aikman in 1989. Solzhenitsyn was indeed the proverbial “little grain” caught between the Soviet juggernaut and a West increasingly bereft of purpose and hostile to the old, humane wisdom that used to animate it.

Whereas Solzhenitsyn always articulated a “healing, salutary, moderate patriotism,” as he called it, his critics associated him with the frenzied and self-defeating nationalism which freely conflated Russian and Soviet things, and that emphatically rejected the path of recuperation and “inner development” that Solzhenitsyn advocated for a Russia freed from totalitarian domination. In addition, Solzhenitsyn was pained by the failure of Western elites to distinguish Russia, the first and principal victim of Communist totalitarianism, from its Soviet oppressors. In a final television interview with Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes fame, this uncomprehending (if not outright malicious) American journalist asked Solzhenitsyn if he was indeed a “freak, a monarchist, an anti-Semite.” In BTM-2, Solzhenitsyn traces the successful efforts of Richard Pipes, the distinguished Russianist and then– Soviet specialist at the National Security Council, to sabotage a planned meeting between Solzhenitsyn and President Ronald Reagan, two great men who profoundly admired each other. Pipes was an honorable anti-Communist, but he was also a scholar who freely identified the Russian tradition with despotism, theocracy, anti-Semitism, and imperialism. He had no feel for the spiritual treasures inherent in the Orthodox religious, theological, and philosophical traditions. He looked at the Russian tradition with much more suspicion than respect. Pipes falsely saw in Solzhenitsyn a dangerous representative of the “Orthodoxy, nationalism, and autocracy” that he identified with “eternal Russia.” In his autobiography, Vixi, Pipes poisonously remarked that not all anti-Communists should be trusted or admired, since Hitler also opposed Communism—a cruel and unjust remark explicitly directed at Solzhenitsyn. This was not Pipes’ finest hour, to say the least.

What was Solzhenitsyn’s relationship with other Russian émigrés?

Solzhenitsyn admired and respected those Russian émigrés (the “First Wave” of émigrés) who fled Communist tyranny after the Bolshevik revolution and the defeat of the White forces in the ensuing Russian Civil War. The same could be said for the Second Wave of émigrés who found themselves in the West as a result of the Second World War and the dislocations that accompanied and followed it. As BTM-2 shows, Solzhenitsyn and his wife Natalia (“Alya”) made significant efforts, and drew on their own resources, to collect an “All-Russian Memoir Library” that saved the memories and experiences of so many whose lives had been turned upside down by the Bolshevik Revolution and the violence and tyranny that followed it. This was an act of love and fidelity, and of profound patriotism, too.

Solzhenitsyn’s relationship with the Third Wave of Soviet émigrés was much more contentious. Many were openly hostile to Russia and made no distinction between ideological despotism of the Soviet sort and the comparative freedoms, and rich spiritual traditions, that flourished before 1917. Many were Soviet men to the core, still defending Lenin, if not Marx, and hardly sympathetic to religion and a rebirth of Russian national consciousness, no matter how moderate or constrained. The Jewish intellectuals in the Third Wave tended to see the right to emigrate as the fundamental human right while Solzhenitsyn insisted that the right to live with dignity in one’s own country was even more important. Some prominent Third Wave intellectuals, especially Andrei Sinyavsky and Efim Etkind, bitterly accused Solzhenitsyn of messianism and fanaticism and worse, and openly stated that he was more dangerous than the Soviet regime itself. Etkind went so far as to compare Solzhenitsyn to the Ayatollah Khomeini, insinuating that the Russian writer favored theocratic despotism, along with new camps and new gulags. Solzhenitsyn responded very effectively to this insidious “Persian Ruse” in a piece in The Jerusalem Post in late 1979. Of course, Solzhenitsyn had some admirers and supporters among the Third Wave of Russian emigration, but they were in a distinct minority.

What did Solzhenitsyn think of Sakharov? What did he make of Gorbachev’s reforms in the Soviet Union?

On the deepest level, Solzhenitsyn admired Andrei Sakharov, the Soviet physicist (and one of the inventors of the Soviet version of the hydrogen bomb). They had engaged together in the great “encounter battle” with the Soviet state in the fall of 1973 that Solzhenitsyn describes so artfully and energetically near the end of The Oak and the Calf. Sakharov was a man of immense dignity and nobility who was moved by “pangs of repentance and conscience,” as Solzhenitsyn put it, to challenge the totalitarian Soviet state he had once faithfully served. His was a “heroic conversion.” And by the mid-1970s Sakharov no longer blamed the Soviet tragedy on Stalin alone, but had come to appreciate the essential corruption of the Soviet enterprise since its founding in 1917.

But this fundamentally good man stubbornly held on to illusions. While rejecting Marxism, he remained dedicated to atheistic humanism and a misplaced faith in “all-round progress,” rule by experts and technocrats, and a world-governing authority in the form of a World Government. Solzhenitsyn was appalled by this scientism (and its hostility to religious consciousness) coupled with a faith in the religion of Progress, World Government, and an apolitical “human rights ideology.” Solzhenitsyn admired Sakharov’s final fight for civic and intellectual freedoms during the meeting of the Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989. Here, near the end of his life, Sakharov was an undisputed voice of truth and civic integrity.

Solzhenitsyn noted that he and Sakharov were of the same age, grew up in the same country, were uncompromising in fighting the same evil system, and were “vilified at the same time by a baying press; and…both called not for revolution but reforms.” Despite their significant differences, as much spiritual as political, they respected and admired each other. Both were undoubtedly heroes who believed in liberty and human dignity and were willing to sacrifice a great deal for that cause. One thing alone divided them: “Russia.” Sakharov was an internationalist and hardly had any deep affective attachment to historic Russia. Thus, in Solzhenitsyn’s chastened love of country, he could only espy a lurking danger for the present and future.

At first, Solzhenitsyn feared that Gorbachev’s reforms were superficial, a new and temporary set of reforms within the broader structure of ideological orthodoxy and state tyranny. Gradually, he came to realize that glasnost did indeed entail the very publicity—and at least partial openness—for which Solzhenitsyn himself had been calling for so many years. Of course, Gorbachev had continuing illusions about Lenin and never freed himself wholly from Communist categories and thinking. Later, Solzhenitsyn worried about a repetition of February 1917, a headlong fall into chaos and disorder in a too-precipitous effort to “democratize” the country and to “liberalize” the economy. The themes of his epic March 1917 were very relevant to this new situation, but the book was not yet available to Solzhenitsyn’s compatriots.

Why did Solzhenitsyn think “explaining things to America” was a thankless task?

Solzhenitsyn admired many things about the United States: the generosity, even magnanimity of its people; the common sense, patriotism, and religious faith of that “other America,” those good people in the heartland, who wrote to him with gratitude after his Harvard Address in 1978. And in his “Farewell to the People of Cavendish, Vermont,” delivered to his neighbors at Town Meeting on February 28, 1994 (and appearing as Appendix 35 in BTM-2), Solzhenitsyn spoke with admiration about “the sensible and sure process of grassroots democracy” that he had witnessed during his eighteen years in New England.

But, over time, Solzhenitsyn painfully discovered that the majority of America’s elite was more anti-Russian than anti-Soviet, and sometimes virulently so. He felt the need to defend the honor of historic Russia, to remain what he had always been, a passionate but moderate and self-critical patriot, even as he continued to fight an inhuman Communist ideology that threatened the whole of humankind. Despite his almost heroic efforts in this regard, including a masterful essay in Foreign Affairs in 1980 entitled “How Misconceptions About Russia Threaten America,” he increasingly acknowledged the failure of his effort to get the West to see that the embattled and oppressed Russia was an indispensable ally in the common struggle against totalitarianism. He lamented the fact that American military strategists targeted Russian cities more than military and political installations.

In Russia today, many patriots, including not a few in Putin’s broad coalition, don’t want anything bad said about the Soviet Union. They conflate it with the very Russia it mutilated for seventy years. Not surprisingly, the Communists and super-patriots in contemporary Russia continue to despise Solzhenitsyn. Nevertheless, under Putin, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Matryona’s Home, and the authorized abridgment of The Gulag Archipelago continue to be taught in Russian high schools. Let it continue to be so.

What were Solzhenitsyn’s impressions of East Asia? Of England?

Japan was in important respects an alien civilization for Solzhenitsyn, and he did not take to its food, or the ritualistic requirement for endless alcohol toasts at major dinners and banquets. But he was deeply impressed by the way Japan had turned from war and tyranny to national self-limitation after 1945, admirably melding significant and sustained economic progress with continued attentiveness to older cultural and spiritual traditions.

Solzhenitsyn’s trip to the United Kingdom in May 1983 was a triumph. His Templeton Lecture, deepening his call for repentance, self-limitation, and humble deference before the Creator God, allowed him to explicate some of his most fundamental religious and philosophical convictions. It remains a favorite among his Western readers. Not ideology or class struggle, but abiding heedfulness to the drama of good and evil in every human heart and soul, remained, for the great Russian writer, the enduring imperative. He was interviewed by two deeply intelligent and sympathetic journalists, Bernard Levin and Malcolm Muggeridge; met Prince Philip, Prince Charles, and Princess Diana, and had a frank and full discussion about world affairs with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. He gave a stirring talk to the boys at Eton and visited Birnam Wood (of Macbeth fame) in Scotland. This is is all conveyed with impressive clarity and charm in the pages of BTM-2.

What was Solzhenitsyn’s reaction to Scammell’s biography of him?

Scammell’s book turned out to be a travesty. While ingratiating himself with Solzhenitsyn and his circle after February 1974, Scammell demanded more and more of Solzhenitsyn time after the British biographer had spent a week with the Solzhenitsyns in Cavendish. Solzhenitsyn gave him access to his as-yet-unknown The Trail (The Road), a seven-thousand-line autobiographical narrative poem memorized in the camps without the help of pen and paper. This allowed Scammell to include valuable material on Solzhenitsyn’s youth and his gradual movement from juvenile Marxism to the mature philosophical Christianity he arrived at in the camps. This is the most valuable part of Scammell’s biography of Solzhenitsyn.

When the book finally appeared after innumerable delays in 1984, Solzhenitsyn was stunned to see how regularly Scammell accused him of vanity, dishonesty, and a lack of self-knowledge, and how little space Scammell devoted to Solzhenitsyn’s art itself. Scammell relied heavily on information provided by Solzhenitsyn’s first, and quite embittered wife, who was by then actively collaborating with the KGB. In addition, Scammell showed a marked hostility to Solzhenitsyn’s deepest intellectual and religious convictions, misrepresenting them at almost every turn.

The book was praised as moderate, balanced, and sympathetic by many reviewers who should have known better. At its worst, Scammell’s biography has the character of an erudite hit job. At a minimum, Scammell was constitutionally incapable of accurately reporting the contents of a book such as From Under the Rubble, edited by Solzhenitsyn in 1974, even though Scammell played a role in its translation. Where Solzhenitsyn and his fellow contributors saw a moral and spiritual manifesto that might help lead Russia out “from under the rubble” of totalitarianism, Scammell read everything reductively in terms of “hackneyed” political categories. He could see in a humane and elevated Christian perspective nothing but blindness to the fundamental dogmas of the Enlightenment. He could not see beyond the limited horizons of Western liberalism—and never tried.

What are some of your favorite parts of the book?

I love the joyful parts and the sense of gratitude that informs it: Solzhenitsyn’s sheer joy in working uninterruptedly on his other masterwork, The Red Wheel, chronicling Russia’s descent into the madness of ideological despotism via the blindness of the liberals and socialists—and a weak Tsar who could only think about reuniting with his family—who together brought Russia the revolution of February 1917. That, not “Red October”, was the real revolution, according to Solzhenitsyn.

I also very much appreciate the author’s wonderful account of the peace he found in Cavendish Vermont, with the help of a loving wife, who also served as his editor, principal critic, intellectual collaborator, and conduit to the outside world. His account of his young sons, at once very Russian and increasingly American, finding their ways in the world, is also moving and instructive.

And the portraits of Solzhenitsyn’s friendly meetings with Prime Minister Thatcher and Pope John Paul II, in 1983 and 1993 respectively, are finely drawn and a tribute to other great souls who fought the common fight for truth, liberty, and human dignity in the age of totalitarianism.

This is a book that both educates and inspires. May it find the many readers it deserves.