Earth Anew: Eco Music from Mahler to Rasmussen (Part II)

Part I of “Eco-Music from Mahler to Rasmussen” broaches the topic of the Weltanschauung in music. By “world view” is meant an adequate understanding of the cosmic complexity of life (to borrow a phrase from Monty Python), the universe, and everything. Does an artist – especially a composer of ambitious scores – grasp the many-layered, spatially and temporally dimensioned super-matrix of what Christian theology calls Creation? In the preening world of postmodernity, the righteous everywhere proclaim an ecological sensitivity, but that same time postmodernism roundly rejects metaphysics, including the venerable notion of a Great Chain of Being. For the materialistic mentality, what can the cosmos be except a mass of resources? It can have no non-material component. It can correspond to nothing living — that is, inhabited by spirit — except in a purely mechanico-biological sense. Now as Part I observes, there is a critical anti-modern strain in modernity. This is more familiar in literature than in music, but it nevertheless presents itself. In music, one finds this critical attitude, with its intuition of a cosmic complexity exceeding the grasp of so-called science, in the radical work of an avant-garde composer like Arnold Schoenberg, but also in the work of a somewhat more conventional composer like Frederick Delius. Part II of “Eco-Music,” beginning with Section III, explores the work of contemporary composers who take an explicitly ecological view of the world, but who also venerate Tradition – and it finds in those works a genuine understanding of the Great Chain of Being. Both Parts of “Eco-Music” remark on the relation between literature, especially poetry, and music.

III. A few phrases from the reigning, reductive ecology, the ecology of “global warming,” occur in the much-polished journalism of the contemporary composer John Luther Adams (born 1953), but they seem decorative or obligatory and never convey any essential meaning. Adams lived by choice in Alaska, near Fairbanks, from the late 1970s until recently. His music takes inspiration from the Arctic landscape and from the traditions of the people who have lived in taiga and tundra immemorially. The reader will encounter Thoreauvian overtones in the accompanimental essay to Adam’s Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing (completed 1996). “Quantum physics has recently confirmed what shamans and mystics, poets and musicians have long known,” Adams writes; and, “the universe is more like music than matter.” In his related “Credo” (2002), Adams echoes Nietzsche: “My faith is grounded in the earth, in the relationships between all beings and all things, and in the practice of music as a spiritual discipline.” Adams accommodates Christianity, which Nietzsche haughtily rejected, in calling it “a complete and beautiful ecosystem” although he makes no profession of the creed. Clouds, one of Adam’s first fully mature scores, draws inspiration from a medieval book of Christian mysticism, The Cloud of Unknowing – and from a natural phenomenon that fascinates vision and activates imagination. The eyes look up to the clouds, just as they look up to the mountain peak. One can climb to the clouds, so as to approach their sublimity, but only by climbing the steep mountain path to the rocky summit.

In glacial tempo… that describes Clouds. Adams creates a Hyperborean sound-world, having one of its bases in his subtle onomatopoeia of the tundra: The sounds of ice fracturing, of shifting winds, and, as if in the Alaskan summer, of insects buzzing and stridulating. Like the Arctic landscape, Adams’ musical panorama seems, at first, static, as if time had ceased. The score of Clouds, dividing the work into nineteen sections, nevertheless follows a plot – from the “Minor Seconds, Rising” of the opening panel to the “Major Sevenths, Rising” of the concluding panel – or not so much a plot, as a pilgrimage. The orchestration draws attention to itself. Adams has scored Clouds for a chamber orchestra dominated by metallophones such as bells, crotales, chimes, and piano, the latter used as a percussion instrument. The flute plays a prominent role. The metallophones assist Adams in translating optical phenomena into aural effects. They mimic in sound refraction of light in an environment of ice, the clouds scattering the solar rays, and the blinding whiteness of the limitless snowfield. Whither the pilgrimage of Clouds? Eliade notes that the “cosmic mountain” of the Siberian shamans has seven levels. The progress through expanding intervals in Clouds, from seconds to sevenths, is analogous to the ascent of the mountain. Another student of shamanism, Geoffrey Ashe, writes in his Eden in the Altai (1992) of the “seven mystique” in Arctic religion, which he derives from “reverence for the sky-center constellation, Ursa Major, with its seven stars.” The ursus is a shamanic totem.

Adams’ Become trilogy consists of Become Ocean (2013), Become River (2015), and Become Desert (2018). The composer scores the two outer installments for full symphony orchestra with an augmented battery; in the middle installment he uses a small orchestra somewhat larger than that of Clouds but much smaller than that of Ocean or Desert. River plays in concert for about half the duration of either Ocean or Desert, each requiring forty minutes in concert, and fits nicely as a centerpiece between them. Become Ocean sets the pattern for the two subsequent scores. Adams unfolds a sustained polyphony of arpeggiated chords in a vast palindromic crescendo-decrescendo. This polyphony is also polytonal, with major and minor chords superimposed on one another throughout. The score resembles the orchestral Prelude to Richard Wagner’s Rheingold, but extended to four or five times the Prelude’s length, and reversing course halfway through. In the Rheingold Introduction, Wagner like Adams composed “water music.” It may well be that Ocean refers to its Wagnerian antecedent. Rivers flow ultimately into the ocean. In addition, both scores have cosmogonic implications and indeed figure forth the evolution of complexity from simplicity in their musical processes. During the unfolding arpeggios of Ocean, a solo instrument or a choir or a mixed ensemble of instruments might hold a single note for an extended period, transforming it into a pedal note. As the arpeggios pay homage to Wagner, the pedal notes reveal a debt to Jean Sibelius, whose late score Tapiola (1925), inspired by the Fennic forest-god, uses them; and whose Luonnotar (1913), based on the Kalevala’s creation story, tells of a cosmic egg hatching in a primordial sea. In its palindromic structure, seven stages with a central climax, Ocean resembles in broad outline Delius’ Song.

Become Desert mirrors Ocean in its structure, procedures, and instrumentation. Adams adds to the orchestral richness of Desert a wordless chorus (shades of Delius) whose timbres he weaves closely into the full texture of the score. An organ announces its presence in a climax midway through, which occurs when a gradual descent into the lower registers reaches its maximum depth, whereupon the re-ascent begins. One can descend into the desert – into Death Valley, for example, whose nadir stands below sea-level. Desert perhaps unsurprisingly conjures a mood not dissimilar to that of Ocean, a desert being a sea of sand and the great expanse of water being desolate and inhospitable. The color, so to speak, of Desert differs from that of its precursor-score, but the psychic goal of the music – to transcend the picturesque by drawing the listener into an altered, presumably a higher state of consciousness – remains the same. The mystical via negativa of The Cloud of Unknowing permeates Adams’ mature work. The metaphor of the desert comports itself with that goal. Think of the Desert Fathers of early Christianity, retreating into the uninhabited drylands in order, without distraction, to break loose from the body so as to intuit the deity. The Cloud of Unknowing author makes the point that the mystical encounter requires as prerequisite the shutting out of anything pertaining to the physical world. He also avows that the mystical experience is good, not only for him who attains it, but, indirectly, for humanity as a whole. It furthers the action of Grace in redeeming a fallen world.

The word ecology and the word economy conform to a pattern. For their first element both words adopt the Greek oikos, “house” or “household.” The differentiating second element of ecology puts the concept to which it refers on a higher level than that to which economy (“the law of the household”) refers. Logos outranks nomos in the cosmic hierarchy; for only when nomos complies with logos does it acquire legitimacy. For the philosopher-mystic Heraclitus, Logos was synonymous with Zeus, the name of the Chief Olympian and the verbal symbol of godhead for Hellenes. The etymological meaning of ecology, betrayed by the small-minded modern usage of the term, is that every level of the universe needs to conform to the structure of the level above it. If not – things go awry. Adams’ citation of quantum physics gains relevancy because, as the physicist, ironically so-called, investigates, ever more profoundly, the depths of matter, matter dematerializes. Modern physics tends to apply metaphors of depth in its discourse, but metaphors of height would be equally appropriate. As the Cloud of Unknowing author writes, up and down are figures of a spatio-temporal orientation. In the search for the Ultimate Principle, there is no up or down, no right or left, no forward or backward, no past or future. Concerning the Word, the tongue or quill can but lamely report. Humanity as a whole cannot untrammel itself from language; the individual, however, pushing language to its metaphorical limit, can gain some glimmering of matrices metaphysical.

The Western emphasis on instrumental music heeds this insight. Wagner wrote his own libretti, but by the time he began to create his Ring he decided that the music should bear the meaning at least as much as the words. The words themselves Wagner took from myth, which avoids the literalness of propositional language and yields its meaning by prodigious indirection. Delius, who adopts Wagner’s chromaticism, deprives the chorus of words in his Song, endowing the voice with a sublimity that it might not have were it to deliver a text. Adams follows suit although he, like Delius, has set texts. Sunleif Rasmussen (born 1961), a Faroese composer, has likewise a relation to Wagner, and, as do Delius and Adams, a reverence for archaic traditions and an explicit yet subtle sense of Nature writ large. The Faroe Islands belong to the Atlantic world of the seafaring Norsemen, who settled them in late in the Ninth Century. As in Iceland, the original settlers followed the heathen lore of the Aesir and Vanir, retaining many heathen customs even after their Christianization. Remote from the regular sea lanes and therefore socially isolated from the mainland of Scandinavia, the Faroese language, like its Icelandic counterpart, has little changed from its medieval substrate. Both the Icelanders and the Faroese found themselves in a harsh or even a punishing environment. They had to live by a necessary asceticism, developing an acute sensitivity to the signs, cycles, and anomalies of their surroundings.

The Faroe Islanders have, in the last few decades, experienced a rebirth of interest in their ancestral ethos. In music, two Faroese have contributed prominently to this revival. Before discussing Rasmussen, therefore, mention should be made of Eivør Pálsdóttir (born 1983), an outstanding singer of ballads and runes, who also fronts a jazz band. Eivør’s video interpretation of the traditional Faroese ballad Trøllabundin (“Troll-Taken” or “Enspelled”), in which she accompanies herself on drum, reveals her awareness of the shamanistic origins of traditional musicality. In an interview (June 2017) with Annie Strange, Eivør says, “There are many layers in the world and many worlds within the world,” and “these are places you can visit.” Eivør makes no pretense of practicing the shamanistic discipline, which would qualify as pretentious, but she affirms the ecstatic mood that singing the Trøllabundin entails. She loves “the pulse” of her drumming, as she tells Strange. Eivør recognizes in drumming “the heartbeat of the Earth.” Trøllabundin “is interesting for me to sing,” Eivør says, “because it’s so naked – it’s just the drum and the vocals.” The lyrics are, in fact, minimal, and most of Eivør’s singing is pure vocalise, no doubt improvisatory. She purchased her drum from a Sami medicine man in the arctic region of Norway. Eivør’s channeling of old boreal culture, whether West Norse or Sami, parallels Adams’ channeling of native Alaskan culture.

IV. Adams’ musical beginnings, as a drummer in a garage band, parallel those of Rasmussen, who also started out in pop music. Eivør sings traditional songs. Rasmussen incorporates folk melodies – inaudibly – in his complex orchestral textures. His technique resists simple explanation. It has to do with partials. Every tone gives rise to a set of partials known as a “harmonic series.” Rasmussen begins with a traditional tune. He extracts from each note a set of its partials. He rearranges the sets horizontally as melodic lines. These lines in their polyphony generate the thematic and harmonic schemes of the musical progress. The effect of this “hidden passacaglia” is one of a skewed tonality, but not, as in serial music, of no standard harmonic reference whatsoever. Rasmussen has brought his procedure to a new level of richness in his two ambitious symphonies – Oceanic Days (1997) and The Earth Anew (2015). Both scores require a large orchestra with the usual augmented battery including chimes and bells. In Oceanic Days, Rasmussen instructs the instrumentalists to double their parts vocally when they can in passages in the third movement. The Earth Anew adds soloists and a chorus, who sing to a text, but the vocal forces also engage in a good deal in wordless melismata. All of Rasmussen’s music springs from his passion for the landscapes and seascapes of his native Faeroes and of the gnarly lore that celebrates its flora, fauna, and humanity. He sees in places like the Faeroes and Iceland theaters of human endurance, whose trials yield grimness and sublimity in equal measure.

Like Adams, Rasmussen holds to an explicitly ecological worldview, but at the same time his work undermines glib modernity and advocates for the validity of tradition. Rasmussen appends to the published score of Oceanic Days a poem of that name by the Faroese poet William Heinesen (1900 – 1991): “Hører du hjertets tusindstemmige koral / om hvad vi bestandig dog må erkende: / vældigt erlivet, / fortids og fremtids magiske skæringspunkt / som står midt i dit levende Jegs.” Man stands alienated from his “living I,” and he stands thus in living death. Wisdom sings its truth to man (“the heart’s thousand-voice chorale”), but man turns a deaf ear to song. Heinesen’s imagery hearkens back to the first step of the mystic journey, self-displacement, as described by Eliade in his treatise on shamanism. The mystic leaves behind him the fragmented self of everyday as he sets out for the Absolute. Rasmussen undertakes a similar journey via his symphonic itinerary and invites the auditor to join in the pilgrimage. Where Adams creates a seamless slow-progress of musical metamorphosis, Rasmussen, by contrast, delights in abruptness and discontinuity. The first movement, Tranquillo, begins with a four-beat descending figure in the tubular bells, which becomes a recurring motif not only in the movement but throughout the symphony. The percussion-interludes that punctuate the movement, colored by the carillon, separate episodes of passacaglia-like chord-sequences in the strings over which the woodwinds weave their onomatopoeias of petrels, gulls, fulmars, and other feather-bearers associated with the islands. In the Largo that follows, the solo cello personifies the seeker, who joins in counterpoint with the parliament of birds. In the final Cantabile, the cello passes its solo role to the tuba. Rasmussen declares that the tuba’s dark timbre represents the deep-diving whale, whose dramatic breaching stands for spiritual breakthrough. The annotator for the Da Capo release of Oceanic Days, Hans Pauli Torgið, remarks that in Rasmussen’s symphony “the ocean is used as a metaphor for the contradictions and absurdities of life.”

The Earth Anew followed about two decades later. Rasmussen’s artistic ambition has meanwhile increased, and so has his sense for the relevancy of lore. The Old Norse myth of Yggdrasil or the World Tree – a yew, as the first syllable tells, not, as often reported, an ash – fascinates the composer. Rasmussen says in a spoken introduction to The Earth Anew that the Myth of Yggdrasil bears appositely on the modern condition. He gives runos from the verse Edda to his chorus and soloists. These describe Yggdrasil and recount how its terminal sickness involves the death of Earth and, after the ultimate catastrophe, a renewal of the cosmos. Wagner told the same story in his fourteen-hour operatic tetralogy, but Rasmussen’s score is concise by comparison despite being on a large scale in four complex movements. The world axis sometimes takes the form of a mountain and sometimes as a many-boughed living trunk, with its upper leafage in the God-Realm and its taproots in Hell, like Yggdrasil. Eliade writes that the World Tree through its roots and branches “connects the three cosmic regions.” The Tree symbolizes, in Eliade’s interpretation, “the sacrality of the world, its fertility and perenniality”; the tree-symbol “is related to the ideas of creation, fecundity, and initiation.” The Edda-verses that Rasmussen puts to music include the creation of the world through the slaying and dismemberment of Ymir, a giant, and the creation of the human race, in the persons of Ask and Embla, both of whom have tree-names. As Yggdrasil sickens, crises afflict the world, culminating in the Ragnarök, the fiery universal deluge during which the conflict of Aesir and Vanir and monsters occurs, entailing pan-cosmic annihilation.

Eliade, in his study, cites items of lore that might explain the fondness for the battery of Twenty-First Century “Eco-Music” composers like Adams and Rasmussen. These citations apply to Eivør, too. Eliade writes how “it is from a branch of [the World Tree] that the shaman makes the shell of his drum.” He adds, “By the fact that the shell of his drum is derived from the actual wood of the Cosmic Tree, the shaman, through his drumming, is magically projected into the vicinity of the Tree; he is projected to the ‘Center of the World,’ and can thus ascend to the sky.” The percussion ensemble pervades Earth Anew even more so than it does Oceanic Days. Descending scalar passages dominate the motivic catalogue of Earth Anew, beginning with the opening Andante espressivo e agitato. The music’s ceaseless agitation no doubt signifies the impending crisis-of-crises, the cosmic ekpyrosis. As in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, things shall first tumble down and then go up in flames. The second movement, Lugubre, is a solemn funeral rite. The third, a Scherzo impromptu, serves for a diversion; it takes its name from Ratatósk, the gossip-bearing squirrel who constantly travels back and forth between Yggdrasil’s roots and branches. The music takes on a burlesque quality, as though it were the meant to accompany a Tom and Jerry cartoon made in the Tenth Century by Vikings; it includes blatant, non-politically correct wolf-whistles although aimed at whom it is hard to say – the Norns, perhaps. The fourth movement, Maestoso furioso — tranquillo e dolce, depicts the Rain of Fire and the subsequent gracious redemption of catastrophe in the new world’s fortuitous and yet inevitable naissance.

What does Eliade’s phrase, “Center of the World,” mean to the modern decentered and deconstructed mind? Likely very little. Works like Das Lied von der Erde, The Song of the High Hills, Become Desert, and The Earth Anew attempt to reimplant the deracinated mind in the soil that ancestrally gave it life, but that mind might be too moribund to recover its spiritual vigor or even to suspect its dire state. In his Decline of the West, Vol. I., Oswald Spengler emphasizes the difference between “human utterance” and “culture-language.” Utterance is utilitarian and purely practical; to it belong “rational procedure and technical experiment.” Culture-language is visionary and spontaneous; to it belong “the various kinds of intuition – such as illumination, inspiration, artistic flair, the experience of life, the power of ‘sizing men up,’” Utterance takes on the guise of “formula, law, scheme”; culture-language articulates itself as “analogy, picture, symbol.” Utterance in a modern context proclaims itself typically in the abstractions of science, so called; culture-language as myth and art. The modern, desiccated mind, Spengler declares, wants to take everything apart in a program of critique. As William Wordsworth put it, “We murder to dissect.” A balanced mind, necessarily informed by lore, knows to defer to contemplation. Spengler quotes Goethe: “Vision is to be carefully distinguished from seeing.” In an age that forbids cognition to exceed “seeing,” the need for contemplation becomes urgent. Rasmussen’s music and the texts that he chooses are, in every way, urgent; but so, too, in their subtler manner are Adams’ music and the texts that inspire him, such as the thematically contemplative Cloud of Unknowing. As Spengler writes, in words relevant, not only to Adams and Rasmussen, but also to Mahler, Schoenberg, and Delius, “The artist’s soul, like the soul of a Culture, is something potential that may actualize itself… in the language of an older philosophy,” whether it is the Neoplatonism of The Cloud of Unknowing, Chinese poetry, or the cosmological speculation of the Edda.

Other compositions deserve mention. Steve Reich (born 1936) composed his Desert Music in 1983. Desert Music, for Chorus and Orchestra, takes its title and its book from selected late Poems by William Carlos Williams. Reich belonged to the original “Minimalist” school of the 1970s along with Terry Riley and Philip Glass, but Desert Music, while building its textures over ostinati, rises above the typical products of the brand. Reich’s technique of serially altering rhythmic patterns gives to Desert Music a mesmeric quality similar to Adams’ Become Desert or Rasmussen’s Oceanic Days. The desert-metaphor reaches back to the Biblical “Voice Crying in the Wilderness,” with its prophetic and futile implication (futile in the short-term, but not as eschatology). Williams writes his verses with the assurance that his readers will connect “the desert,” not only with the Old Testament, but also with the development of nuclear weapons. There is the terrible light of the nuclear detonation, but there is also the ineffable light of grace: “Inseparable from the fire / its light / takes precedence over it.” Williams also touches on manifestations of transcendence: “Is there a sound addressed / not wholly to the ear.” Later, “I am wide / awake. The mind / is listening.” The Mind… John Pickard (born 1963) composed his Symphony No. 4, Gaia (completed 2003) for a combination of brass band and percussion. Pickard’s music makes a different impression from any of the other composers mentioned in this essay, but in the eeriness of its final movement, “Men of Stone,” it conjures the sublimity of Britain’s megalithic dolmens and rings. Pickard creates an atmosphere of somberness and sacrality. The attentive ear catches hints of prophecy and magical utterance.

Prophecy – alas! – always fails. That is the fate of prophecy, to fail. Art, including music, to the extent that it strives prophetically, always fails. Prophecy and art reach too few among the many to alter what impends, but to those who listen with the ear attuned or who look with the eye illuminated, prophecy and art at least reconcile disappointment. They do so in two ways: First by their stubborn nonconformity – to the extent, in the case especially of the prophets, that their communities murder them; second by revealing the complexity of being, the interconnectedness of the parts in the Whole, and the transcendence of the Whole over the mere manifold of the parts. The knowledge is worth it. The knowledge is itself participation in the Whole, even if vicarious, through the shaman or mystic. Of course, such knowledge is primary for the artist. Spengler, in The Decline, puts forward the thesis that instrumental music furnishes the culmination of the peculiarly Western artistic impulse, which begins in the architecture of the Gothic Lady Church. A yearning for infinity gives rise to Western – or, as Spengler names it, “Faustian” – art. The flying buttress and the ogive strain to connect Earth with Heaven and in so doing strain equally to dematerialize themselves. The polyphony of the Renaissance and Baroque ages consists in dematerialized architecture – and the instrumental compositions of the Sonata Era and Romanticism even more so. Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Frederick Delius, John Luther Adams, and Sunleif Rasmussen – not to mention Reich and Pickard – are musical prophets. They speak in vatic phrases before a contemporary society that, to its own detriment, never listens.

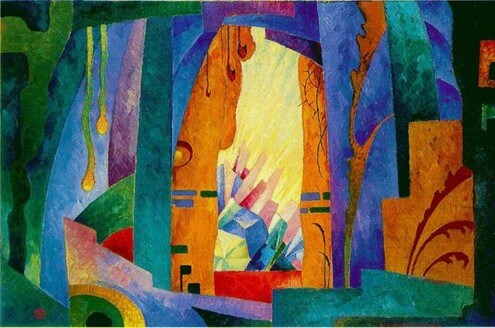

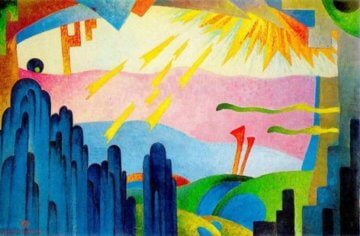

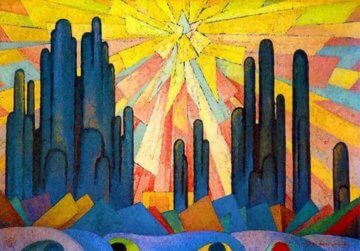

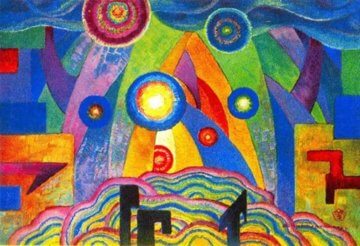

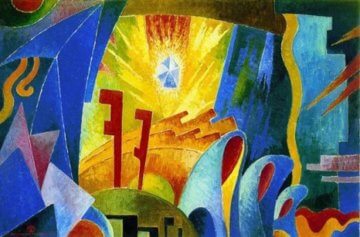

A Note on the Gallery. Joseph Anton Schneiderfranken (1876 – 1943), also known as “Bô-Yin-Râ,” the name he assigned to his paintings and books, described himself as a metaphysician in attitude and, with qualifications, as an expressionist in art. One associates him with Central European figures from the first half of the last century such as Rudolf Steiner, Hermann Keyserling, and Stefan Georg. Whereas a coterie of devotees keeps alive the names of Steiner, Keyserling, and Georg, Schneiderfranken has largely slipped from memory. His Worlds of Spirit – a suite of paintings first exhibited in Vienna in 1921 and later published in book-form with an accompanying text – nevertheless constitutes a masterpiece and deserves to be known. The sub-title of Worlds of Spirit (the book) is “A Sequence of Cosmic Perspectives.” Schneiderfranken’s “Sequence,” like the musical scores reviewed in the body of this essay, implies an ecological view of Being and Existence deriving from Late-Antique Neoplatonism, Christian mysticism, as in the writings of Dionysius the Areopagite or The Cloud of Unknowing, and late-medieval German authors like Meister Eckhart and Jakob Boehme. As mentioned earlier, The Cloud of Unknowing provided a source of inspiration for Adams in at least one of his works. Adams is a composer and Schneiderfranken was a painter, but Schneiderfranken’s art, prose and painting alike, is also musical. He writes, for example, of “a resonance to inner harmonies” as prerequisite to visionary attainment and of the “rhythmically articulated motion” that proceeds from the “Word of the Beginning.” Schneiderfranken’s verbal figures could apply to the music of Adams and Rasmussen: “You witness ever new configurations gaining shape; you see their outlines ebb and flow, continuously interweaving with each other until, amidst this endless wealth of forms in motion there arises, in increasing brilliance, the radiant gem in which the Word then knows itself.” The shamanic ascent makes its presence known in the Worlds of Spirit image-sequence and its prose commentary. The cosmic mountain appears explicitly in Himavat: “The distant peak of purest white that shines amidst a sky of flaming gold is HIMAVAT – the sacred mount where those alone have their abode whom the primordial Light of the Beginning chose itself to be its consecrated kings and priests on earth.”

The cosmic mountain signifies distance, height, therefore also depth, and a panoramic view of the whole, as discussed in connection with The Song of the High Hills by Delius in Part I. These same themes – and they are thematic in the literary sense, not just functional in the compositional sense – appear in all the images of Schneiderfranken’s World of Spirit and in his painterly oeuvre generally. Schneiderfranken’s relation to the “eco-music” composers, however, exceeds thematic similarity. Schneiderfranken’s images aspire to the musical – to the polyphonic and contrapuntal. While they necessarily freeze the motion that they depict, the mind of the connoisseur, responding to the symbolic cues, reestablishes that motion. Take Te Deum Laudamus as an example, with its liturgical and musical references. Schneiderfranken builds into his vista six levels of depth from foreground to background. (The number of stages in the shaman’s mountainous ascent, as Eliade remarks, is typically six.) The viewer finds himself drawn through the layers to the backmost layer wherein floats the radiant, six-faceted jewel, the sign of the demiurgic god. Since the dynamism of the layers can only be simultaneous, Schneiderfranken creates the visual analogue of polyphony, partly constituted by the contrast between curves and angles, and partly by the presence of the four traditional elements, which clash and reconcile. Neither music nor painting uses propositional language, but then the dimensions that music and painting reveal have their being, as the mystics divined, beyond grammar and analysis. In this way, Schneiderfranken’s images have nothing to do with abstraction; they are purely expressive, as he defined Expressionism: What is inner is given utterance. And what is inner relates not only to the consciousness of the person, but to the ambient consciousness of the total environment which utters itself by borrowing human self-awareness.

This is the second of two parts with part one available here.