East of Appomattox: Where Old Times Are Still Not Forgotten

One of the great joys of Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee is that when I am out hiking the mountainous landscape of the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains, I often come across plaques, placards, and other signs dedicated to Civil War memory. Being an Ohioan by birth, many of these memorials have a special significance to me: many of the Union forces in this region of the war were from Ohio. When in Roanoke, Virginia, after hiking the Triple Crown of the Appalachian Trail, I decided to walk a battlefield trail within the city to pass the time while waiting for a blues band performance at a brewery.

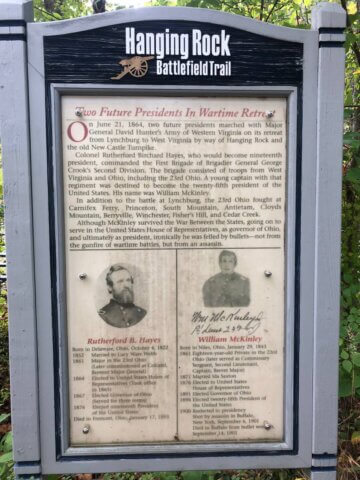

Hanging Rock battlefield, where Union forces were defeated by a Confederate cavalry raid as they fell back from Lynchburg in 1864, is an odd battlefield since it lacks the splendor and majesty of Manassas or Gettysburg. It is just a winding gravel trail alongside the roads of the city, flanked by trees and the gentle rushing water of Mason Creek. Walking through the lush vegetation and singing birds with the occasional whoosh of a passing vehicle, to my surprise a poorly kept memorial placard along the trail informed me that two future Presidents from Ohio were Union officers during the engagement: Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley. Surprises like this make these moments special. I had no idea and wasn’t planning to do another 5 miles of walking after having just hiked 20 miles earlier in the day while waiting for a musical performance at a local brewery as the night sky approached.

Like many Americans who developed a fascination with history, the American Civil War was my first love and gateway into studying history. My father was a part-time reenactor during his spare time, and we attended those small and even large-scale reenactments when young and the replica musket that he used hangs on the fireplace mantle of his home back in Ohio. I was raised on Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary. There were some John Wayne movies sprinkled in too. Not to mention Gettysburg. Then there were the trips as a child to battlefields like Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. Somewhere in an attic in Cleveland, Ohio, there is a cardboard box of old polaroid photographs of me and my younger brother walking those sacred grounds somewhat oblivious to the sacred memory these parks were established to preserve and pass on to new generations.

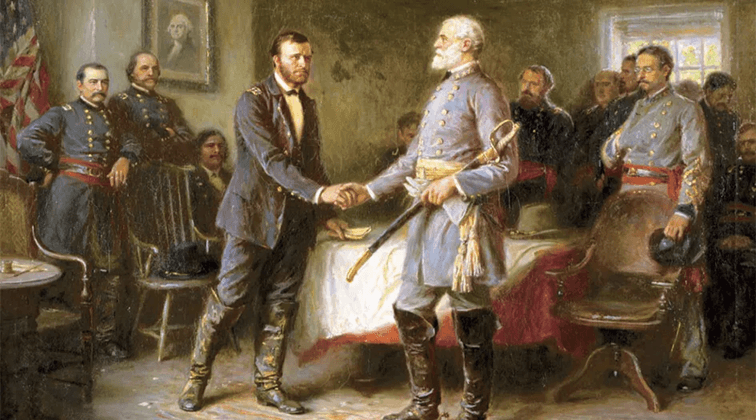

The Civil War is a contentious episode in American history. In part because of the extensive post-war mythology that was constructed in the reconciliation between the white north and white south, at the exclusion of black Americans. The mythology of the Lost Cause still runs deep, especially on social media, even though secession documents state very clearly the intent to preserve the institution of slavery as among the reasons of the southern states leaving the Union. We know the tempered Lost Cause mythology: The Civil War was tragic but both sides fought bravely, honorably, nobly; this stands in contrast to the more Unreconstructed Confederate mythology which portrays Lincoln and the Union as vile, vindicative, and militant tyrants who victimized a good, moral, and Christian southern people. Sometimes this Lost Cause mythology says it was a war that need not have been fought. But the war was fought. It was tragic, but the Union prevailed, and the United States came out a strong nation because of it and that unified United States of America would prove indispensable in the terrible and ferocious wars of the twentieth century which set a captive humanity free. We are all probably familiar with this tempered version of Civil War memory and legacy.

History is not merely facts as dilettante amateurs often claim on the Internet and the world of social media. History is really the collective memory and the stories from that collective memory of events that people tell. Stories glorify. Stories vilify. They use the same facts but the conceptual relationships that the storytellers have to those facts shape their telling of the stories. As an Ohioan by birth, one of the most important Union states during the war, I was raised with pride for the Union but a respect for the Confederacy: they were wrong but nevertheless fought bravely. Ohio was, after all, the state that gave the Union William Tecumseh Sherman – the general who made Georgia howl – and the aforementioned Hayes and McKinley who were memorialized in that plaque in a forest gravel trail in Roanoke, Virginia that I decided to walk waiting for a band to arrive and play music at a local brewery I was to spend the evening.