Evolution’s Mistress: Darwinian Evolutionary Theory and Its Discontents

“Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist; he cannot live without her but he’s unwilling to be seen with her in public.” —J.B.S. Haldane[1]

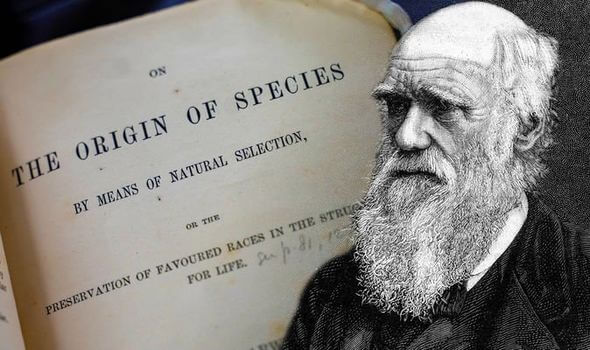

Charles Darwin is hailed today, together with the likes of Galileo and Newton, as one of the patriarchs of our modern scientific worldview. Countless scientists have sung the praises of the evolutionary theory that Darwin set forth in the latter half of the nineteenth century, beginning the the meteoric On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life in 1859 and continuing with The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1868 and The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871. The first of these works laid out his “theory of evolution through natural selection,” as it is called.[2]

The second explored the manifest ability of human selection in more or less controlled environments to alter the features of animals and plants and argued that an analogous process was operative in nature albeit without the foresight and intention provided by human selection. The third of these works applied the theory of natural selection to the human being, arguing that the same processes by which sphagnum moss and paramecia happened to emerge also led, by chance, to the existence of humanity. Interestingly, Darwin also proposed another parallel process of selection in this work, called “sexual selection,” that is generally regarded as peripheral to evolutionary theory but which entails a very different conception of the origin of species than the ordinary view of the so called “Neo-Darwinian synthesis,” which merely indicates the interweaving of Darwin’s theory with Mendelian genetics. I will find occasion to elaborate on this point later in the course of this exploration. Suffice it here to observe that Darwin’s theory is generally hailed as one of the great advances in scientific history and its author has entered into the quasi-mythic company of other great figures science’s long march of progress. Stephen Jay Gould called Darwin’s theory “one of the half-dozen shattering ideas that science has developed to overturn past hopes and assumptions, and to enlighten our current thoughts.”[3]

Ernst Mayr left no room for equivocation about the place he awarded to it among the history of ideas when he declared that “The theory of evolution is quite rightly called the greatest unifying theory in biology.”[4]

Peter Medawar granted no quarter to its detractors when he opined that, “For a biologist, the alternative to thinking in evolutionary terms is not to think at all.”[5]

Indeed, Darwinian evolutionary theory is generally taken to be a settled datum vis-á-vis the origin of lifeforms on the Earth, and if you ask a member of polite society today, he will proceed as though the matter had been settled long ago and could countenance no further objections.[6]

In other words, he regards the theory as an observable fact and imagines that only pseudoscientists and religious fanatics would have anything further to say on the subject.

But anyone who attempts to employ a theory in the manner that is only appropriate to observations made in light of that theory has already departed from the path of science, properly so-called. As the master himself observed, “All observation must be for or against a point of view.”[7]

It will immediately be objected that “scientists use theory in a manner that is more sophisticated than laypeople and hence I am playing on an equivocation of the term to cast aspersions on the legitimacy of the science.” But the manner in which scientists employ the term is not really more sophisticated than the manner by which it is employed in common parlance. It is not uncommon for particular fields to develop technical and often idiosyncratic meanings for words and the use of the term “theory” in many of the sciences is an example of this. A theory is, in the most essential sense, a way of seeing.[8]

A theory is not only intended to explain what can be readily observed without the said theory. Instead, the function of a theory is to disclose a phenomenon to begin with. A great deal more could be said on this point, and I will have occasion to return to it again at a later time. Here, this brief comment alone was warranted in order to preempt a common misunderstanding vis-á-vis theory: to wit, that it can be conceived as merely as a datum of perception rather than the condition and capacity by which observation and perception may proceed and without which they cannot. If it were possible to “extract” a theory from a phenomenon of perception, the perception of the phenomenon would go along with it.

As a rule, proponents of the Darwinian theory in a manner that would only make sense to treating a finding made in light of that theory. In other words, they do not consider the manner by which a theory does not pertain to the category of scientific fact. Instead, a theory embodies a whole way of seeing, or world-view. In this manner, all scientific facts and observations are transcendentally beholden to their correlative theories. For instance, when the philosopher Daniel Dennett, who has taken up the mantle once bestowed on Thomas Huxley as “Darwin’s bulldog,” makes a statement like the following:

Love it or hate it, phenomena like this exhibit the heart of the power of the Darwinian idea. An impersonal, unreflective, robotic, mindless little scrap of molecular machinery is the ultimate basis of all the agency, and hence meaning, and hence consciousness, in the universe.[9]9

It is necessary to consider the theory tacitly operative and subtending the supposed observation of “mindless scraps of molecular machinery.” Obviously, “mindlessness” is not perceptible to sensory observation and neither is it directly measurable by scientific analysis. Instead, it is necessary to possess a “theory of mind” or a “theory of agency” as a condition to observe eventual instances of these phenomena when they do appear. Lacking a theory of mind, no instance of mind will be accessible to perception any more than a person who had never heard of chess could perceive a chessboard were it presented to him. It is an axiom of Darwinian evolutionary theory to discount the existence and hence operation of mind in nature except vis-à-vis instinctual activity directly indexed to survival and reproductive fitness of an organism. That is the reason for the conflict between the Darwinian theory of evolution and any theory of “intelligent design.” The Darwinian paradigm proposes intelligence, and life, for that matter, as a sort of cosmic accident that was purely the result of random events. Tautologically, something must avoid non-existence if it is to propagate through time. Hence, that intelligence and life eventually arrived on the scene, so it is supposed, is the result of “intelligence-like” and “life-like” phenomena that immediately preceded them, which were in turn preceded by “intelligence-like-like” and “life-like-like” phenomena and so on back to the Original Mystery. Obviously, whatever is said about the nature of the universe before our arrival on it, one thing for certain is that it is the kind of universe in which the potential for life was present from the origin. Coming to grips with this point already entails loosening one’s grip upon the Darwinian paradigm.[10]

But let us grant the hypothetical series of events that accidentally consummated in intelligence and life as the Darwinist imagines it—hypothetical given that it defies observation in principle because the sensory organs that we find ourselves equipped withal required the entirety of that very evolution to appear and hence could not have furnished us or anyone else with observations at the times in question—it must be acknowledged that the same series of events could have just as well been the result of an intelligent orchestration and design. Indeed, speaking on an evidentiary basis, neither the fossil record, nor the observable behavior of organisms, would need to be any different to accommodate one of these views over the other, let alone the speculative histories that the scientific imagination is compelled to weave. The only difference is, when presented with the evidence in question, the Darwinist would merely explain its emergence on the basis of his own preferred theory. Namely, that all life is the result of evolution through blind instinctive processes, happenstance, and natural “selection.” This judgement is axiomatic under the Darwinian paradigm and hence it holds irrespective of what that evidence in question happened to be—whether it be the eye of an orca, a chloroplast, a feather in the tail of a peacock,[11] or the fact that the likes of Darwin, Dennett, and Dawkins bother to compose their copious texts arguing in support of Darwinian evolutionary theory.

But there is a further concern with the Darwinian evolutionary theory aside from its ineluctably conjectural nature and the fact that it may not pass the “falsifiability” criterion that Karl Popper advanced as a sine-que-non of scientific theory.[12]

Consider Richard Dawkins’ definitive statement on the subject:

Wherever in nature there is a sufficiently powerful illusion of good design for some purpose, natural selection is the only known mechanism that can account for it.[13]

Whereas to the naïve observer, the passage above could only be explained on the basis of the argument that its author intended to advance, by the logic of that very argument, the ultimate reason for its composition can be nothing of the sort. Instead, it must be axiomatically traced back to the genetic fitness that similar activities conferred on their distant ancestors, which natural “selection” identified and preserved through the chaos of generations. In the same way, all organisms in nature, together with every feature of every organism may seem to evince the presence of intelligence by its design, but would belie its true origin. Dawkins elaborates on this view:

Natural selection, the blind, unconscious, automatic process which Darwin discovered, and which we now know is the explanation for the existence and apparently purposeful form of life, has no purpose in mind. It has no mind and no mind’s eye. It does not plan for the future. It has no vision, no foresight, no sight at all.[14]

Hence, the appearance of purpose in nature is, in a certain sense, an elaborate hoax. And of course, so too is the appearance of purpose “outside” of nature or inside of us. I realize the formulation is awkward but let the reader see past my clumsy articulation to grasp the point that I am attempting to elucidate. Namely, that Darwin began by proposing the purposelessness of nature by arguing that blind, natural “selection” could accomplish a task in every way comparable to artificial selection by human purpose. This argumentative arc is captured in his follow-up to On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life in 1859 with his The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1968. Consider then, as manifest in the third epochal publication in this series, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871, where this logic must lead. The selection that appeared to be purposeful in nature, and comparable to manifestly purposeful selection in the case of human breeders, was shown to be blind. But then human beings themselves were shown to be an outcome of this same process. In other words, Darwin’s approach to explain the existence of purpose was ultimately to show that it does not exist.

In most company, it is considered bad form to explain a thing by claiming that the thing wanting of an explanation is not really there. But Dennett has built his career on advancing an argument in every way comparable to this in the context of philosophy of mind and the so-called “hard problem of consciousness.”[15]

“The existence of consciousness and first-person experience appears enigmatic and redundant in the context of physicalist accounts of nature and, Q.E.D., consciousness and first-person experience do not exist,” is approximately the logic deployed by thinkers of this persuasion. Dennett, for instance, repeatedly refers to consciousness as a “user-illusion.”[16]16

Of course, the existence of these things is just as difficult to explain if they are an illusions as if they are real, and, a fortiori, it’s not clear how one would imagine one could get a start at an explanation if what one were proposing—that consciousness did not exist—were true. But it is not the idiosyncratic theories of consciousness and neuroscience that Dennett and other similar thinkers have advanced that are on trial in the present essay, but the Darwinian evolutionary theory.

And yet, the two issues are not really two. After all, mind is an intensification of life, and not something disjunctive with it. Darwin’s theory of evolution was by no means the first theory of evolution. Lamarck, von Humboldt, Goethe, and even Immanuel Kant, had all advanced views of evolution before Darwin came on the scene. Darwin’s theory differed only in that it promised an explanation of life without mind by appealing instead to “the blind, unconscious, automatic process” in Dawkins eloquent paraphrase for “natural selection.” As intimated above, the explanation is proffered in bad faith because “selection” entails a teleological disposition whereas the latter is precisely what the Darwinian theory attempted to extirpate from other evolutionary theories. Lamarck, for instance, notoriously postulated that the neck of a giraffe elongated as a result of its constant striving for leaves on the uppermost boughs. That the emerging science of epigenetics is retroactively vindicating Lamarck to a great extent is an import point that I will find occasion to return to later. Darwin, however, attempted to explain the length of a giraffes neck in abstraction from the intentions and mind of the giraffe. Instead, nature was “selecting” for longer necks by arranging environmental influences such that giraffes with longer necks attained competitive reproductive advantage until, over vast spans of time, the grotesque proportions that we know and love had been attained. Of course, the fact that natural selection working over eons of time could explain the appearance of teleology in the structure and behavior of the giraffe begs the question at issue because lacking the teleology inherent in the instinct inherent in virtually all life to survive and propagate its kind, the presumed mechanism of evolution would not be present to begin with. In other words, the mechanism of evolution depends for its function and existence on something manifestly not mechanical but intentional, even if not consciously so. In other words, natural selection can only explain teleology by presupposing it.[17]

But something further must be noted in respect to the question of evolutionary trajectory. Why, it must be wondered, did Adam the giraffe not go the route of a zebra and thereby spare his progeny to trouble of thousands of years of evolution? Darwinian theory can never answer this question. It can, of course, offer post hoc rationalizations of given changes. But a theory that makes no viable predictions—in this case, vis-à-vis, future speciation events—fails to fulfill one of the essential criteria of scientific theory altogether.[18]

But even granting evolutionary theory is a viable scientific theory, to conceive of environmental influences driving natural selection still presents two significant problems. First, the organism-environment dichotomy is a false one. Every organism’s environment is comprised of every other organism, and in turn, contributes to comprise the environment of each of those others. “Environment” is, hence, a relative term, comparable to directions like “left” and “right” and not to cardinal directions. Yet the Darwinian theory is only coherent if “environment” is treated as an absolute designation. It makes no sense to say “the environment is exerting some influence on a creature who is itself blindly subject to this influence” when that creature itself is part of the environment. Moreover, organisms are continually shaping and influencing their surroundings. Cyanobacteria created the oxygen bloom that wiped out most of the life on Earth in that time, beavers build dams that divert waterways, and the transformative prowess of homo sapiens is notorious, “replenish the earth,” God said, “and subdue it” (Gen. 1:28).

But the above difficulties are comparatively trivial when set against the fundamental oxymoron entailed in employing the term “selection” to designate the “the blind, unconscious, automatic process” that is being imagined. Either selection is taking place or a “blind, unconscious, automatic process,” but it can’t be both. In the second case, the outcome is due to chance. But “chance” is not an explanation for something, but a tacit admission that an explanation is still wanting. To explain something as random is not necessarily false, but it is to defer having explained it. It is not unlike the old German saw that says “if the cock crows atop the manure pile, then either it will rain or it will not.” Everything seems like it is happening by chance until it is understood. Cold is not a kind of heat, but the privation of it and chance is not an explanation but an indication that an explanation has yet to emerge.

Again, proponents of the theory of natural selection will object that their view is substantiated on the basis of evidence. But I tried to show how the evidence for such a claim, while appearing to ratify the theory at issue, actually presupposes it as a condition to make the observations necessary to substantiate it. It is impossible to gather observational evidence in support of the Darwinian view of life unless one has first come to see the purposeful activity of living things as illusory. However, seeing the purposeful activity of organisms as an illusion was never self-evident. Instead, it was a function of the very theory one is purporting to ratify through the observations.

A still further problem arises in respect to the semantic content of the theory itself. We must ask ourselves how the scientific method could possibly establish that life “has no vision, no foresight, no sight at all” when any evidence for such a claim must already, by its very existence, entail the very intentionality that it purports to deny. After all, neither scientific theories nor evidence for them just falls from trees. Dennett declares that “apparently purposeful life has no purpose in mind.”[19]

But where is the scientist in his theory? One of the fundamental tenets of Darwinian evolutionary theory is the common origin of all life, including scientists and philosophers. Once you have rejected the existence of something like purpose or foresight, and supposed to have gathered observational evidence for its non-existence, you can never be certain that a further observation will not disclose the very thing you had resolved to deny, thus upending the entire theory.[20]

Similarly, identifying “chance” as the cause of an event is tantamount to conceding that the cause remains unknown because there is not way to distinguish the perception of randomness from mere lack of apprehension.

But in fact, the reasons to be skeptical of the Darwinian theory and its proponents are much more severe than they may at first appear. To illustrate this point, let us imagine that the theory is entirely correct, together with the natural corollary that all of our mental and emotional functions also derive from adaptive and reproductive advantage they conferred on our forbears—a view known under the rubric of “evolutionary psychology.” It would entail that Darwin, Dennett, Dawkins, and the like, by the logic of their own theory, are arguing for it on the basis of adaptive and reproductive advantage, and not on the basis of truth. The only possible criterion for “truth,” in the Darwinian universe, is “fitness.” On this view, all science and philosophy would necessarily be reduced to bullshit, in the technical sense[21] because what had professed to be an instance of reasoned dialectic and argumentation surrounding first principles and experimental method was, in fact, an elaborate mating ritual and survival strategy. If the Darwinian theory were true, we would not be capable of knowing it because our minds, axiomatically, evolved to survive and reproduce and not to discover the truth of things. If they managed to hit upon the truth of things, it would be by accident and hence could not really be known, for can someone who doesn’t know whether a thing is the truth really be said to know the truth? A theory transcendentally beholden to premises that it negates is a theory in need of improvement.

Before concluding, I would like to venture a few remarks on the significance of epigenetics and Darwin’s theory of “sexual selection” to the reigning paradigm of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis. Both of these elements challenge the conventional view of “the blind, unconscious, automatic process which Darwin discovered” as the explanation for life’s diversity. Instead, epigenetics and sexual selection re-introduce the phenomenon of purpose, agency, and more generally, teleology as such back into evolutionary theory from the inside, which is where they belong to begin with.

It is a premise of the Darwinian view that the genome of an organism is conserved through its interaction with its environment. The epigenome—that is, not the genome per se but the relative expression or suppression of different genes—can undergo substantial changes brought about directly by that organism’s action and interaction with(in) the environment. This is a straightforward and uncontroversial characterisation of these terms. To this can be added the observation that the given potentialities for behaviour, or affordances, that any organism possesses will determine its “fitness” in respect to a given environment. “Adapt and breed, or die and perish,” as the Darwinian axiom goes. Again, this principle of “natural selection” is understood to be the primary factor responsible for evolution of that organism’s genome according to the paradigm of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis. In other words, if we ask where the genome comes from, the answer is that it is the heritage from the reproductively successful members of the prior generation. Again, the reproductively successful members of a given generation, from which the genome of the next generation are inherited, are those members which are assumed to have been able to draw on potentialities of behaviour best-suited to their environment, broadly construed. And yet, at the same time, the epigenome—operating within the comparatively broad constraints of the given genome—is the primary factor responsible for the given potentialities of behaviour that that organism possesses. Genes only code for proteins if they are active and the genome does not code for activity of itself. Instead the epigenome serves this role of determining the activity or latency of given genes. This suggests a reciprocal interaction of the genome and epigenome. Behavior shapes the epigenome which modulates the genome which determines form and potentialities of behavior for that organism. Notice this series ends where it begins. This connection reveals the active role that an organism contributes in shaping the evolution of its own species, which evolution can no longer be ascribed merely to “the blind, unconscious, automatic process which Darwin discovered.”

Darwin’s theory of sexual selection, if it had been adequately incorporated into the general Darwinian paradigm, would have similarly begun to overturn it for the same reason. In brief, after having presumed to have explained the origin of species through natural “selection,” which was held to function merely on the basis of reproductive fitness and without any appeal to purpose or intention on behalf of organisms, Darwin realized that his theory of natural “selection” in fact entailed the very thing it was celebrated for having circumvented. To wit, organisms actually do select their mates. As a rule, it is often the females of a species that are the more selective and, ipso facto, intentionally participate in the evolution of their species. That is an example bona fide selection and hence I did not place it in quotation marks.

NOTES:

[1] Quoted in Hull, D. (1973). Philosophy of Biological Science. Prentice-Hall.

[2] The five parts of Darwin’s Theory are: 1. Evolution and not static types (Evolutionism); 2. The lineage of all organisms from common ancestors through genealogy (Realgenese); 3. The appearance of new species while retaining the original species (The Principle of Divergence); 4. Evolutionary changes in small steps (Gradualism); 5. The survival of adapted genetic variations and the natural decline of those that are less adaptable (Natural Selection)

[3] S.J. Gould, The Flamingo’s Smile: Reflections in Natural History, 1985.

[4] E. Mayr, Populations, Species and Evolution, 1970.

[5] P. Medawar, The Life Science, 1977.

[6] If this were the case, it would not be the first time that the boot was, in fact, on the other leg in respect to the most fundamental issues, and the person most complacently self-assured of his apprehension of the truth in these affairs were in fact the one least possessed of it. In a recent essay, I treated a comparable issue under the rubric of “wisdom” rather than “truth.” Self-evidently, the concepts bear an intimate relation. Wisdom is, in a general sense, condition and manner by which truth manifests in consciousness.

[7] Charles Darwin, The autobiography of Charles Darwin: 1809–1882, New York: W. W. Norton, 1861, 161.

[8] Our English term stems, as will be familiar to many, from the Greek word theoria, composed of the Greek roots θεωρία, thea “a view, a sight” + horan “to see”).

[9] D. Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, 1995, 202–3.

[10] Statistician William M. Briggs lays out the reason why we ought to summarily reject outright the dismissal of design on a purportedly scientific basis:

What about the rest of (if you will) creation [beyond man]? That must have been designed, too, in the following analogical sense (if I’m going to be misquoted, it’s going to be here).

You’re asked to design a carnival game for kids, a sort of junior wooden pachinko device. Ball goes in at the top, rolls down a board hitting posts along the way, bouncing to and fro, finally coming to rest in one of four slots at the bottom, A, B, C, and D, which, although it’s not part of the analogy, correspond to certain prizes.

Before the ball is dropped nobody really knows which of the slots will have the ball. All sorts of things will cause the ball to land where it does, from the friction of the ball, board, and posts, the bounciness of and wear on the ball itself, the humidity and temperature of the air, even the gravitational field; and many more things comprising the Way Things Are operating on All There Is (the machine and its environment).

Nobody can track all these causes, yet they must be there, because otherwise how would the ball get where it’s going? One thing is clear, the ball can only land A, B, C or D. It cannot land E nor F nor any other letter because these slots do not exist by design.

Evolution is just like that. However changes occur to an organism, whatever mechanism causes genes to shift, the eventual organism must “land” in, and be caused to land in, some slot, or biological niche if you like. Viable organisms are like the slots of the pachinko game, and non-viable ones—the beasts that cannot live because their genes will not produce a living being in a particular environment—are like the slots that aren’t there.

No scientist knows, and more importantly no scientist can know, that the slots we see weren’t designed, weren’t planned for. And the same is true for the slots we don’t see. The reason is simple: whether the slots were designed is not a scientific question, but a philosophical one. Science can tell us what we’ll see given a set of rules (the Way Things Are), but science, as we learned, must be mute on the big question: why these rules?