Existential Shakenness and Transcendence

Those committed to inherent human dignity and rights may, or may not, focus attention on the transcendence of the “absolute” that validates them.

If they do, they may decide that it is fruitless to ponder this transcendence—since, well, it “transcends” our ability to know anything substantive about it. So what would be best to do, they may decide, is acknowledge it to oneself (perhaps avoiding, as the UDHR does, any overt metaphysical or religious elaborating), and then turn attention to the social and political work of securing or shoring up recognition of dignity and rights.

In this way people can affirm that there is a transcendent reality without this acknowledgment becoming for them in any way an existential difficulty.

But it may be argued—as Kierkegaard is famous for doing—that if this transcendent absolute is not a difficulty for one, then one is not really “affirming transcendence.” For, Kierkegaard would say, as soon as transcendence has become “just another fact,” it has lost its living truth.

This is because the essence of a relationship with transcendent reality is uncertainty: uncertainty about its meaning as the ground of the cosmos; uncertainty, consequently, about why there is a cosmos of which it is the ground; and finally, uncertainty about the ultimate purpose of one’s own existence, since existence is one’s participation in the cosmos and its ground.

If this is the case, then arriving at a truly personal, truly inward affirmation of transcendence involves a certain kind of existential drama.

The twentieth-century Czech philosopher Jan Patočka has described the drama in this fashion.

Everyday existence, he says, typically takes refuge in embracing life in the world as essentially non-problematic. That is, people normally accept some foundational truths about the meaning of existence ass given and certain. All sorts of problems of existential importance have to be dealt with in life, of course, starting with whether or not to take life seriously. But rarely do people question matters all the way down to first principles, to the point that the why and wherefore of the cosmic ground itself comes into question and is allowed to become problematic.

If a person radically questions “received givens and certitudes” about the cosmic ground, there follows a certain liberation from “accepted and ordinary” routines of existential perception. But! This is achieved only through the more or less anxious discovery that the essence of such “open” existence—existence in relation to a problematic cosmic ground—is what Patočka calls an unsettling “spirit of free meaning bestowal.”

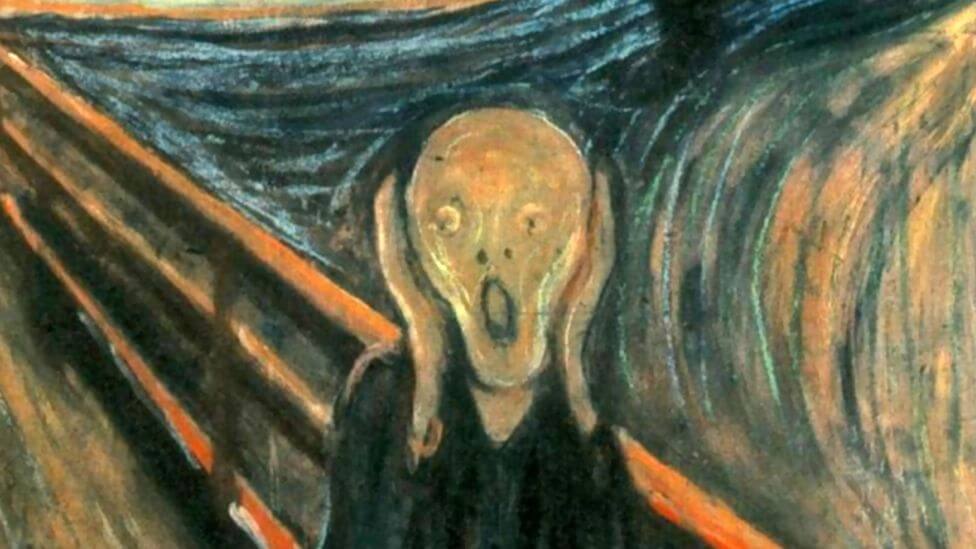

This phrase, “free meaning bestowal,” should not be understood as suggesting that a person, through such openness, discovers that “meaning” is merely a human invention, or that “reality” is whatever a person decides it to be. Rather, Patočka is alluding to an experience in which culturally absorbed pre-given certitudes about the ground of the cosmos (certitudes such as: “the ground of reality is the gods and goddesses we have worshipped for as long as we can remember,” or “the ground of reality is whatever ‘energy’ turns out to be when, finally, it is understood mathematically”) are disrupted—so that life and its answers undergo what he calls an elementary “shaking”—a “shaking of life.”

In such experience, radical questioning dissolves not only all “known,” but (and this is key) all knowable answers about the ground of the cosmos. It discloses the ground of being to be an eternal mystery—a Beyond that is truly transcendent, epistemologically and ontologically—to which the “shaken” soul must remain, if authentically affirming it, in a relation of perpetual questioning. In such a “shaken but undaunted” posture of inquiry, a person comes to realize (here meaning both “to recognize” and “to make real for oneself”) three things:

1) that the ground of reality is meaning that is an abyss of mystery;

2) that the source of human freedom—of the ability of personal freedom to bestow as-yet-only-possible meanings, as it navigates existence—is the dizzying “no-thing” of transcendent freedom; and

3) that participatory freedom in this abyss of mystery is human existence.

Obviously, not everyone is willing to sustain the recurrent existential openness to ultimate uncertainties involved in such a “shaking.”

So, in Patočka’s view, it is not to be expected that what Václav Havel called the “general human experience of the absolute” will produce in many people—much less universally—a grasp of the fact that words so unthreatening as “the unconditioned,” and “the transcendent” are actually, in their historical and existential origins, intimately related to shaken experiences of a cosmic abyss of mystery.

Yet these are the experiential origins of living notions of transcendence, as testified to by countless mystics, philosophers, prophets, artists, and saints, East and West, over the course of millennia.

(This, just to be clear, is an “existential shakenness,” not a kind of emotional distress. It does not make it difficult to eat breakfast, or to do one’s job.)

When a person recognizes the validity of such experiences, it becomes impossible to avoid becoming aware that in the human understanding of reality there lies a core of both existential ignorance and of linguistic incapacity. To appreciate that we are participants in a transcendent abyss of mystery means grasping, first, that this mystery “incomprehensibly lies beyond all that we experience of it in participation”; and second, that it can be spoken of, or artistically represented, “only by characterizing it as reaching beyond all symbolic language” (Voegelin).

(To state this in positive terms: a person knows that humans participate in a ground of reality that can never be adequately understood, and knows that the content of the ground can never be adequately represented in speech, music, art, etc.)

“Shaken openness to transcendence” thus alters the conscious negotiating of our being-in-the-world. As indicated, it entails relinquishing a presumption of cognitive mastery over the ground of meaning—a presumption we never consciously decided upon, but rather absorbed unconsciously as we imbibed cultural givens regarding “reality.” (How could it be otherwise than that, when very young, each of us found elementary existential balance by unthinkingly accepting basic assumptions regarding the Whole and its ground?)

But also, such openness and shakenness alters the character of our relationships with other people.

For when I discover that the essence of my own existence is participation in the infinite value of a transcendent absolute, I see also, on the basis of how I now relate to this and that person who has become (in Buber’s language) a Thou for me, that all persons are participants in the infinite value of the absolute, and so infinitely precious, and constantly vulnerable—which means that my responsibility to each person is also “infinite,” which is to say: unconditional.

What is an “unconditional responsibility”? A responsibility that has no boundaries, no limits, and no excuses. And though it is impossible for me to live up to such a responsibility (see Dostoevsky on the matter), I acknowledge it.

Finally, this “shaking of life” reveals to me that others have undergone a similar experience of disruption, and have remained open to repeated disruption through holding onto uncertainties about the ground of being. (Most of these I meet in the pages of books, or through art; some I meet face to face.) Thus a community of the “shaken but undaunted” comes into view, a community established (as Patočka states) on a unique solidarity: “the solidarity of the shaken.”

Members of this community are drawn naturally toward commitment to the principle of universal inherent dignity because they share witness to the transcendent absolute that is the ground of inherent dignity and rights.

How odd: that revelation, in shakenness, of the abyssal mystery of the ground of existence is one of the means by which respect for universal dignity is strengthened and maintained.