Getting “Woke” with Socrates

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

–Maya Angelou

The term “woke” is associated with increasingly widespread efforts to diversify faculty and to “decolonize” pedagogy along with curricula. Classics, a field centered on millennia-old European languages, texts, and history, provides a tempting target.

The New York Times, in addition to highlighting controversies about Howard University’s recent termination of its Classics Department, also published a massive profile of Princeton classicist Dan-el Padilla Peralta. According to Peralta, one could not surpass classics as “a discipline whose institutional organs and gatekeeping protocols were explicitly aimed at disavowing the legitimate status of scholars of color.” Peralta elsewhere exhorts professors to ask themselves this question: “What steps am I taking to ensure that students from underrepresented backgrounds see themselves in Classics and its sister disciplines?” The remainder of my article explores how Plato can be used to help university students from such backgrounds—and many others—find themselves validated and enriched by his dialogues. I shall focus on the Apology of Socrates, a short dialogue that is probably the most widely read text from ancient Greece or Rome. Although it does not discuss race, it provides powerful tools for antiracism.

Some of the Apology’s most famous lines link it to “woke” ideals such as enlightenment, transformation, justice and critical thinking. In his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King, Jr., draws on it to extol “nonviolent gadflies” who “help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism.” Athens, Socrates famously asserted, resembles a large and “rather sluggish” horse that needs to be “awakened” by the “gadfly” (30e), and he proceeded to proclaim that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (38a).[1]

Contemporary readers can also relish the subtle brilliance with which the Apology illuminates the situation of minorities confronted by biased and potentially murderous majorities. As Joshua Adams elaborates, “woke” was introduced by African Americans, who for centuries were impelled to name “systems of oppression in order to avoid, subvert and eventually dismantle them”; to “navigate” perilous social conditions, they need “deep understanding” along with “vigilance.”

The detailed portrayals of Socrates issued by individuals who knew him—Aristophanes, Plato, and Xenophon—all trumpet his eccentricities and the fragility that his deep “difference” entailed. Millennia later, Nietzsche described him as “the single turning-point and vortex” of world history (The Birth of Tragedy, §15). Plato’s Apology, however, also renders him an unforgettable everyman.

Few readers conclude that the Apology and other dialogues convey transcripts of things the historical Socrates said, and I’ll follow the majority of scholars by discussing the version of Socrates that Plato labored so hard to immortalize.

THE DEFENSE COMMENCES

The duality between difference and conformity surfaces in the very title. Despite Socrates’ prominence in other Platonic dialogues, only the Apology of Socrates includes his name in the title. And it presents him as an individual defending himself against the collective (“apology” transliterates the ancient Greek term for a trial defense). Here are the opening words:

How you, men of Athens, have been affected by my accusers, I do not know. For my part, even I nearly forgot myself because of them, so persuasively did they speak. And yet they have said, so to speak, nothing true (17a).

The accusers, per standard procedure, spoke first at the actual trial. Although Plato doesn’t convey their attack, Socrates’s opening highlights the impact accusations can have on victims; the impact is particularly salient for the innumerable readers who already know that Socrates was condemned and executed. There stands Socrates, claiming that his accusers have lied pervasively—but so potently that he “nearly” believed their devastating portrait.

Socrates will proceed to play the underdog card on multiple occasions. The opening, however, exaggerates so manifestly that it practically begs readers to refrain from absorbing his claims in an “unexamined” manner. The “so to speak” is a hint, and he also invites scrutiny a bit later when he asserts that the accusers had said “little or nothing” true (17b). Like the rest of us, it seems, Socrates is willing to exaggerate. And insofar as the opening conspicuously refrains from acknowledging whatever truths the accusers had conveyed, we are invited to hypothesize that Socrates will sometimes exaggerate more than a “little.”

Socrates immediately adds that his speech will deliver “the whole truth” about himself (17b). How could Socrates—or any 70-year old—deliver such an account within a few hours, especially when speaking unamplified to 500 jurors (supplemented by the “men of Athens” who were observing the trial)? Although Plato’s dialogues have been “canonical” for millennia, they routinely invite us to question them relentlessly. The Apology’s opening soon adds another implausible promise: that Socrates will proceed to speak “at random” in whatever words he “happen[s] upon” (17c).

Here again, I would argue, the text invites an “inclusive” pedagogy. I typically invite my students to conduct small-group discussions (e.g., Think – Pair – Share) about the following question: Based on the opening, how eager would you be to have Socrates as a professor? The diversity, creativity, and humor of the answers always bring Socrates to life. They also give me tips about how to be a better instructor.

Teaching familiar materials, many professors struggle to slow down their delivery, and the small-group format allows every student to respond at a comfortable pace. By encouraging students to judge the text, furthermore, such exercises reduce the intimidating presence of professorial authority and can encourage them to challenge the priorities that infuse the syllabus. Anyone teaching controversial materials, e.g., critical race theory, can proceed similarly. I regularly invite my students to question the relevance of old books and to introduce contemporary developments that illuminate something in the text.

However bizarre the “at random” promise is, it suggests another pedagogically fertile theme that pervades the dialogue. Socrates will obey the law (19a), and he regularly accommodates expectations that were deeply rooted in Athens. But he will never forget himself, and his defense speech repeatedly confronts the powers-that-be with his idiosyncrasies. Even individuals who today swim in “privilege” cannot live without conforming to an array of potent norms and expectations. My students regularly invoke phrases that capture this. Regarding jobs as well as relationships, people need to “choose their battles”—e.g., “what hill to die on”—and to deliberate about “pushing the envelope” or “rocking the boat.”

The dialogue’s title highlights Socrates while placing him in a legal/political cage, but the gadfly keeps flying toward the slats. As the opening unfolds, indeed, Socrates asks the audience not to “make a disturbance” if he speaks in his customary manner; being “foreign” to the judicial “manner of speech,” he is basically an outsider with whom they would “sympathize” by tolerating “the dialect and way in which [he] was raised” (17c).

THE FIRST ACCUSERS

The dialogue pivots as Socrates introduces and elaborates “the first accusers”: Aristophanes and others who long ago persuaded “the men of Athens” that Socrates was “a wise man” who investigated “the things aloft” (along with “all things under the earth”) and who “makes the weaker speech the stronger.” This long section (18a – 20c) poses obvious challenges to every contemporary reader; among other things, we encounter two different versions of the first charges, and the second also accuses Socrates of “teaching others” (19c). Regarding the science-tinged charges, Socrates does assist the audience (and readers) by tracing the grave danger these charges allegedly posed because the Athenians attributed atheism to such investigators (18c).

My students readily appreciate the challenges of religious toleration. With an eye to antiracism and inclusive pedagogy, I stress the threats that prejudice has always posed. Socrates emphasizes that “the first accusers” addressed his audience “at the age when you were most trusting, when some of you were children and youth.” His plight was heightened because “no one spoke in my defense” and because (apart from Aristophanes) he was unable even to “know and say” the accusers’ names (18c-d). Students from marginalized groups can easily relate to this, and I doubt that anyone gets through life without confronting “envy” or “slander” (18d) that other people learned as children.

Socrates proceeds to liken the challenge to “fighting with shadows” (18d), a compelling metaphor. Prejudice can be summoned by an array of conspicuous traits, including sex, gender, race, age, height, weight, attractiveness, musculature, hairstyle and disability, not to mention attire and accent. We can rarely be certain that people we meet don’t judge us immediately with suspicion, fear, or hostility; for many groups, so-called microaggressions provide repeated reminders of widespread biases that contribute to subordination and mistreatment.

When Socrates finishes responding to the first accusers, he seems to realize he has created a puzzle. Modelling a technique that everyone sometimes employs, he raises a question on behalf of a listener: “Well, Socrates, what is your affair?” (20c). Many first-time readers, likewise, have wondered why Socrates, who had just differentiated himself vigorously from the atheistic scientists—and from the money-seeking sophists (19d-20c) who taught amoral techniques of persuasion—is even on trial. To address this, Socrates shares a famous story that highlights his uniqueness: how the oracle of Delphi’s clam that “no one was wiser” (21a) launched his life of unrelenting questioning and arguing.

“WHAT RIDDLE IS HE POSING?” (21b)

The Delphi section of the Apology (20c – 24b) displays peaks of both accommodation and confrontation. The accommodation dominates insofar as Socrates presents his unique and deeply rooted philosophical identity as a mission for the god Apollo (the oracle of Delphi); we find out later that impiety is a key charge in the actual trial (24b). The deference in the Delphi section is accentuated by the confrontation Socrates implies subsequently when he condemns “the unexamined life”: if such a life is simply “not worth living,” Socrates would presumably have philosophized without any spur from an oracle. Socrates’ account of this spur, moreover, provides a dense mixture of defiance and deference.

The deference assumes these forms, among others: the “witness” of Socrates’ wisdom is “the god in Delphi” (20e); his friend who trudged there to ask the priestess about Socrates was Chaerephon, a “comrade of your multitude”; Chaerephon also shared in the “recent exile” of democracy-loving Athenians who had fled the city after the victorious Spartans (in 404 BC) imposed an oligarchy (the so-called Thirty Tyrants) on Athens; Socrates doesn’t mention his former associates, Critias and Charmides, who belonged to that oligarchy; Socrates claims that he endured poverty and ridicule because of his pious mission for “the god,” who made him a messenger to demonstrate that human wisdom is “worth little or nothing” (23a); while listing politicians, poets, and artisans as the targets of his ongoing questioning, Socrates omits sophists, with whom he converses at length in dialogues such as Gorgias, Protagoras, and Euthydemus.[2]

The defiance within the Delphi section is manifest primarily in Socrates’ relentless attack on human competence, starting with the politician who was Socrates’ first victim. This politician “seemed to be wise, both to many human beings and most of all to himself” (21c), but he probably knew nothing “noble and good” (21d). The poets, meanwhile, allegedly knew “nothing of what they speak” (22c).

Socrates concedes that the artisans he examined, although they erred by presuming that they grasped “the greatest things” (22d), did display formidable knowledge of their crafts (22d); to use contemporary terminology, Socrates here “owns” his privilege as an intellectual who benefits from the expertise and effort of artisans. He proceeds to highlight the economic sacrifices caused by his life-consuming questioning: he lived in “ten-thousandfold poverty” because of his “devotion to the god” (23c). Although Socrates routinely speaks about artisans and their crafts (e.g., carpentry, shoemaking, and weaving) in Plato’s other dialogues, however, he never speaks with them.

The disruptive and corrupting impact of these encounters was amplified by their public character. Socrates boldly asserts that certain youth—the “sons of the wealthiest,” who “have the most leisure”—follow him around and enjoy witnessing his examinations. In addition, “they themselves often imitate” him and unmask numerous individuals who “pretend to know, but know nothing.” To salvage their reputations, the latter proceed to repeat “the things that are ready at hand against all who philosophize” (23c-d), in effect allying with the first accusers. Hearing about the affluent youth who constituted Socrates’ entourage, some listeners would doubtless have been reminded of Critias and Charmides.

“MELETUS, THE ‘GOOD AND PATRIOTIC’” (24b – 28b)

Although Socrates quoted from Aristophanes’ Clouds to illustrate how the jury’s minds were poisoned against him, he provided no other evidence to document the hatred that the first accusers allegedly spawned. When Socrates finally gets around to confronting the charges for which he is actually on trial, Plato provides a first-hand portrait of Meletus, one of the three current accusers. This section of the Apology highlights both the combative Socrates and the conciliatory one, but the former dominates. Socrates also provides poignant illustrations of the temptation to scapegoat, which remains an obvious threat to innumerable people today.

Socrates caters to general expectations along with the trial’s legal constraints when he specifies the actual charges, which are interrelated: “corrupting the young”; and believing in “novel” daimonia (see below) rather than in “the gods in whom the city believes” (the Greek verb for believing, nomizein, encompasses observances along with beliefs). Even here, however, Socrates breaks from the cage by introducing imprecision. He prefaces the elaboration with the words “something like this” (24b), and he follows it with the phrase, “of this sort” (24c). Apart from reminding everyone of his ineffable uniqueness—while subtly deprecating the authoritative stature of Athens and its courts—Socrates here is also undermining himself as an authority by inviting listeners and readers to assume a skeptical posture. As several of my students have suggested, he might even be hinting at martyrdom: Is he courting conviction and execution in order to reduce the prospects that future patriots like Meletus will constrain investigators like Socrates? Few readers, indeed, are persuaded by the summary Socrates provides at the end of this section: that the indictment against him “does not seem . . . to require much of a defense speech” (28a).

“Critical thinking” invites us to notice that, as he proceeds to outwit and flagrantly insult Meletus, Socrates adds plausibility to something he had merely asserted in the Delphi section: that no one could stand up to his questioning. Without delving into an array of important details and speculations, I’ll proceed to share several points that students usually relish in this section.

Regarding corruption, Socrates offers two main themes. First, he maneuvers Meletus into asserting that everyone in Athens but Socrates is good for the youth (25a). Socrates thus seems to warn us about the urge to scapegoat, which remains a plague on every continent. He begins by noting that someone who can identify “the one who corrupts” should also be able to identify who “makes them [the youth] better” (24d). When pressed on this, Meletus is initially reduced to silence, and readers are invited to question the patriotic arrogance Meletus manifests by trying to execute a dissident. And perhaps individuals who are eager to “cancel” Critical Race Theory—not to mention dead white males such as Plato, Shakespeare, David Hume, and Dr. Seuss—should generally be less confident they can distinguish what corrupts from what improves.

Socrates’ second main theme is this: because corrupted citizens are dangerous, no one would voluntarily corrupt, so Athens can simply educate Socrates rather than punish him (26a). Although this line of argument echoes the “virtue is knowledge” hypothesis from other dialogues,[3] it includes obvious absurdity; students quickly grasp how the evils eagerly inflicted by rapists, murderers, and meth dealers illustrate Socrates’ exaggeration. The punishment vs. rehabilitation issue remains profound, however, and my progressive students relish the implications for restorative justice, drug courts, and other alternatives to incarceration.

Regarding the gods, Socrates induces Meletus to blunder seriously in a very different manner. Responding to Socrates’ request that he elaborate the charge, Meletus insists that Socrates is not merely a theological innovator: he is an atheist who “declares that the sun is stone and the moon is earth” (26d).

In responding, Socrates conspicuously downplays his nonconformity by suggesting that he, like “other human beings,” divinizes the “sun and moon.” When he then suggests that Meletus has confused him with Anaxagoras (26d), an earlier philosopher who fled Athens after being accused of impiety, Socrates in effect placates the community by scapegoating Anaxagoras; he says nothing here to acknowledge that late philosopher’s profound impact on the young Socrates (Phaedo, 97b-98b). And a surprising twist comes when he points out that Anaxagoras’s books are readily available in the market (26d-e). Although the Apology gave Athens a bad rap, Socrates here and elsewhere (e.g., Republic, 557b-e) acknowledges its remarkable intellectual and cultural blessings.

Once Meletus accuses him of atheism, Socrates can easily humiliate him by invoking the official charge about novel “daimonia.” Socrates provides a detailed proof that no atheist could believe in daimonia (26e-27e). These lines reinforce Socrates’ refusal to defend atheism. Careful readers, however, should perceive how defiant Socrates is by evading the question of whether he believes in the gods of Athens.

“A JUST SPEECH” (28b-34b)

The next section is so rich and provocative that even an hour-long class can barely plumb its depths. I shall again cut corners.

This section launches with another hypothetical question: “Then are you not ashamed, Socrates, of having followed the sort of pursuit from which you now run the risk of dying?” The questioner, we might infer, feels incompetent to refute the proofs Socrates just offered, but anticipates the trial’s outcome; the questioner also highlights the shame people associate with deviance. In what follows, Socrates dances both delicately and vigorously between accommodation and confrontation.

In the memorable opening, Socrates likens himself to Achilles, who knew that avenging his friend Patroclus would precipitate his own death. Socrates here indulges the Greek exaltation of Achilles, and even describes the latter’s mother (Thetis) as a goddess. Socrates proceeds to add a patriotic pitch—one is obliged to remain, despite the danger of dying, wherever one was “stationed by a ruler” (28d)—and he mentions three battles where he risked his life for Athens (28e). Accentuating the skepticism he earlier proclaimed regarding “the greatest things” (22d), he adds that “no one knows” whether death isn’t “the greatest of all goods” (29a).

Although such skepticism supports the battlefield courage that most societies celebrate, its nonchalance about death accentuates Socrates’ status as an outlier. Students, moreover, readily perceive the distorted defiance the 70-year old egghead conveys by likening himself to the legendary 20-something warrior. Between the lines, furthermore, readers are invited to recall the sequence of events that ultimately killed Patroclus; Achilles, motivated by wounded pride, had disobeyed his commander (Agamemnon) by withdrawing from the Trojan War.

Giving his audience the benefit of the doubt, Socrates proceeds to suggest a compromise some of them might welcome. Would he agree to stop philosophizing if they acquit him? His response reaches new peaks of both combativeness and ingratiation. Having received such a hypothetical offer, Socrates says, he would speak these words:

I, men of Athens, salute you and love you, but I will obey the god rather than you; and as long as I breathe and am able to, I will certainly not stop philosophizing. . . . (29d)

The “certainly not” clause conveys resolute insubordination, but that is softened dramatically by the “salute,” the “love,” and the appeal to “the god.” Socrates does not appeal to his identity, his rights, or his conscience. There is subtle but significant defiance, however, when Socrates presumes that Chaerephon’s report of the priestess’s ancient assertion (“no one was wiser” than Socrates [21a]) converted his philosophizing into something that “the god orders” (30a), a claim to divine guidance Socrates will elevate a few pages later (33c). On the flip side, Socrates proceeds to imply that he routinely lauded Athens as “the city that is greatest and best reputed for wisdom and strength” (29d).

The plot thickens further as Socrates gives a new—and far less skeptical—account of what his philosophizing entailed. Socrates earlier identified his wisdom with humility, with the universal human ignorance regarding “the greatest things.” Now, however, Socrates maintains that he’d basically been a preacher, exhorting everyone to realign their values: to care less for money, reputation, honor, and bodies but more for “the things worth the most” (30a), i.e., prudence, truth, soul, and virtue. Although the earlier skepticism would strike most Athenians—and millions of people today—as corrosive or corrupting, this new type of confrontation has a conspicuously moral tone. So perhaps Socrates wanted it to soften the defiance he had just conveyed. He proceeds to describe himself as “the gift of the god to you”; he is the unique gadfly responsible for awakening the horse-like “city” (30e) by “going to each of you privately” and “persuading you to care for virtue” (31b).

From here, Socrates delivers another batch of captivating elaborations. Implying that the listeners might now wonder why this “busybody,” so forthcoming “in private,” never sought to engage “your multitude” and “counsel the city” (31c), Socrates invokes his remarkable daimon. The daimon is a “voice”—or “sort of voice”—that “always turns me away from whatever I am about to do, but never turns me forward” (31d). By vetoing “political activity,” the daimon kept him from dying prematurely. With an implied nod toward his earlier belittling of death (29a), he adds that a dead Socrates “would have benefited neither you nor myself” (31d). Socrates then returns to rebuking: “there is no human being who will preserve his life if he genuinely opposes either you or any other multitude and prevents many unjust and unlawful things from happening in the city” (31e). This statement begs for a Think-Pair-Share discussion, which could be launched by diverse questions. To what degree—or in what places and circumstances—do Social Justice Warriors need to heed the warning? Which is generally worse: the threat the “multitude” (plêthos) poses to a handful of idealistic dissidents or the threat that the wealthy and powerful pose to ordinary people? To what extent is the “multitude” more destructive than plutocrats, demagogues, fanatics, psychopaths or tyrants?

Anticipating that his audience might dismiss lofty rhetoric as insincere, Socrates now offers evidence based in “what you honor, deeds” (32a). He sketches two situations where he was apparently compelled to engage in political activity (recall his service as a soldier and the compliance he has displayed regarding judicial proceedings). In both, he opposed injustice and thereby incurred danger.

The first example would have seemed particularly provocative because it develops his anti-democratic critique of the “multitude.” When certain judicial responsibilities were imposed on him via ordinary procedures (including a lottery), Socrates appealed to the law when arguing that a group of ten naval generals should be tried individually. The city was then “under the democracy,” and Socrates’ wording greatly personalizes the clash: “although the orators were ready to indict me and arrest me, and you were ordering and shouting,” I sided with “the law and the just rather than side with you out of fear of prison or death when you were counseling unjust things” (36b-c; emphases added).

The second example painfully reminds his audience about the brief reign of the Thirty Tyrants, installed by Sparta after Athens had lost the huge conflict (the Peloponnesian War) during which the generals were tried. The government ordered Socrates and four other men to round up Leon the Salamanian, an innocent wealthy man whom the oligarchs proceeded to kill and expropriate. Unlike the other four, Socrates risked death by disobeying.

If nothing else, the addition of this example to the democratic one suggests that Socrates—and perhaps all genuine philosophers—would detect flaws in any real-world government, and his defiance of the oligarchy gains salience because of Critias and Charmides. There are additional circumstances in this deftly composed segment that soften the anti-democratic implications of the first example, not to mention Socrates’ disparagements of “the many” (25b, 28a, 36b). Regarding the generals, Socrates added that “all of you” eventually realized that the group trial was illegal (32b). When describing the Thirty Tyrants, by contrast, Socrates never hints that any of them came to regret any of the evils they had inflicted, and he amplifies their cynicism by sketching the reasons they commanded ordinary citizens to arrest Leon: “they ordered many others to do many things of this sort, wishing that as many as possible would be implicated in the responsibility” (32c). But Socrates relays a final challenge to the democratic jury by providing a bland rendering of how he disobeyed the Thirty: he simply “went home” (32d). Listening to this phrase, some jurors presumably wondered whether Socrates should have done more. He could have attempted to warn Leon, to join the exiled democrats, or to rebel against the oligarchs.

It takes time for students to absorb the associated historical details, including the body count—Leon was executed, as were the six generals who hadn’t previously fled or died—and the horrors Athens experienced by fighting and losing the Peloponnesian War. It is nonetheless easy for students to identify and reflect upon parallel situations in our century: e.g., the violence the U.S. inflicted abroad after the trauma of 9/11; the ruthless and sometimes genocidal cynicism of various world leaders; the temptation to cut corners when prosecuting criminals; the impulse to designate scapegoats while seeking fixes for serious problems.

In reckoning with the powers-that-be, Socrates was addressing Athenians who were exclusively male, and one can easily invoke feminist perspectives when discussing his plight. Men are not a majority, but their general edge in size, strength, and testosterone escalates the damage their irrationality does. In the play Ajax, for example, Sophocles memorably captured how female wisdom is obscured by toxic masculinity. The mighty warrior Ajax is about to leave his tent, in a delusional rage, to slaughter an array of herd animals that he mistook for Odysseus and other leaders who had dishonored him. When his concubine Tecmessa gently tries to talk him down, Ajax replies “curtly . . . in well-worn phrase” before proceeding to inflict the mayhem: “Woman, Silence is the grace of woman.”

“WHATEVER AM I WORTHY OF?” (35d-38b)

This section begins after the jurors took the vote that found Socrates guilty. Because the laws about corruption and impiety didn’t specify a punishment, the jury had to choose between the execution Meletus had proposed and an alternative proffered by Socrates.

Socrates ended up proposing a fine of 30 minae. He could scrape together “say, a mina of silver,” but four of his friends (including Plato and Crito) “bid” him to propose 30 times that amount as “they will stand as guarantors” (38b). The jury chose the death penalty. If, as a prominent ancient source (Diogenes Laertius, 42) indicates, the second vote was more one-sided than the first, the Apology seems to explain why.

This section includes one of the dialogue’s most inflammatory passages, in which Socrates argues that the city should grant him a lifetime of free meals in the Prytaneum (36d-37a), the sacred hearth of Athens. According to historians, this is the way that Athens honored and rewarded its greatest heroes. Playing on the legal language for punishment—what the convicted defendant should receive as his “desert”—Socrates speculates about what he is truly “worthy of” as a “poor man” who had been engaging “privately” with everyone to “perform the greatest benefaction” (36b). Having just reminded the jurors of his mission as gadfly, he reiterates his idiosyncratic persona with these words: “I did not keep quiet during my life and did not care for the things that the many do,” including “moneymaking” and politics (36b). He proceeds to deliver the most confrontational sentence in the Apology:

So if I must propose what I am worthy of in accordance with the just, I propose this: to be given my meals in the Prytaneum.

I always launch an extended small-group discussion here, posing the following question: How admirable—or how wise—does Socrates seem in the above-summarized deliberation (36b-37a)? My students have generated all sorts of illuminating assessments. On the one hand, Socrates is conspicuously defiant and reckless, as if the men who voted to convict him of corruption and impiety are so corrupt and ignorant that their judgments are utterly inconsequential. Socrates, moreover, brazenly mocks the legal system and culture of Athens by asking to receive the maximum public reward as the alternative to the maximum public penalty (execution). Many students nonetheless admire the way that Socrates allows neither the verdict nor the prospect of execution to derail the rigorous deliberative thinking to which he devoted his life. He refuses to cower or bow before the state, despite its multigenerational heritage and the deadly force it is always ready to deploy. Many students perceive something comparably noble: that here, as earlier, Socrates might be courting martyrdom to empower future gadflies. With assistance from Plato and others, Socratic education has continued for millennia on multiple continents.

Socrates does not pause to allow a vote after the “meals in the Prytaneum” line, however, and he in effect continues to think out loud before he officially proposes the fine. In this segment, Socrates is more deferential, but he continues to provide major spurs to our wakefulness.

After reminding everyone that he doesn’t know whether death is “good or bad,” he considers three alternatives—prison, fine, exile—before settling on the fine. He discusses prison very briefly, simply lamenting that he would be living in jail, “enslaved to the authority that is regularly established there” (37b-c). People who distrust authority can easily applaud, and there is a subtle implication that tempers Socrates’ arrogance. Prison—like the Prytaneum—would provide him with shelter, food, and endless time to think (perhaps he could even bring along the books of Anaxagoras). The isolation, however, would basically extinguish the opportunities to learn in person from other people. Granted, Plato elsewhere highlights the loner side of Socrates (Symposium, 174d-175c).

Socrates’ commitment to conversation is highlighted in his much longer assessment of exile. This assessment extends several olive branches. First, Socrates suggests that the jury would grant him exile as the alternative to execution. Second, he doesn’t expect that he’ll be better received anywhere abroad than he had been received by his “fellow citizens.” Third, it would be grim for an old man to live out his days “exchanging one city for another, always being driven out” (37d). For the last time, moreover, Socrates suggests a reasonable hypothetical response and then supplies a captivating reply:

Perhaps, then, someone might say, “By being silent and keeping silent, Socrates, won’t you be able to live in exile for us?”

The warmth and calmness of these words is even more striking because the guilty verdict has been rendered and execution is looming ever closer. Emphasizing how hard it would be to persuade certain people about why silent exile is not an option, Socrates first says “you will not be persuaded” if he answers that he’d thereby be “disobey[ing] the god” (37e-38a). His second explanation centers on the famous claim that “the unexamined life” is simply “not worth living for a human being.” This explanation, he concludes, would be “still less” persuasive (38a). We now have additional reasons to think that the Delphi-based account of his mission was partly an accommodation to the religiosity of ordinary Athenians.

“TO DELIVER ORACLES” (38c-42a)

After the jury votes for execution, the official procedures are completed. But few readers are surprised that Socrates has more to say. And insofar as Socrates was, all along, concerned more to improve the future than to extend his life, we would expect his wisdom to shine brightly in his last words.

The martyrdom thesis receives additional support as Socrates finally highlights that his “age is already . . . close to death” (38c). He directs that remark particularly to “those who voted to condemn me to death” (38d). Socrates continues to address them for several pages, mostly in scold mode. At one point, indeed, he seems to lash out with rage:

I desire to deliver oracles to you, O you who voted to condemn me. For in fact I am now where human beings particularly deliver oracles: when they are about to die. I affirm, you men who condemned me to death, that vengeance will come upon you right after my death, and much harsher, by Zeus, than the sort you give me by killing me (39c).

Unless the class is farther behind than usual, I stop here to engage in an unusual exercise. I first ask everyone to scrutinize the passage while thinking about how Socrates would have delivered these words. Then I ask for at least two “readings,” one with intense calm, the other with intense anger.

This exercise requires every student to think energetically about how emotional Socrates would have been—and about what goals, long-term as well as short-term, he would now be trying to promote. The exercise also encourages students to contemplate the differences between reading and listening. By varying volume and pacing, the students can offer dozens of plausible renditions of 39c. In all of his dialogues, I maintain, Plato invites the serious reader to assume a comparably active posture.

Having finished the theatrical renditions, we return to the text, where the next few lines establish that Socrates’ rage was merely feigned—and that the “by Zeus” was an oath, not a prediction that Zeus will lash out. What vengeance awaits the enemies of Socrates? Escalated nitpicking, it seems. There will be “more who will refute you, whom I have now been holding back,” refuters who will be younger and therefore “harsher” (39d). Before the first vote, Socrates had emphasized his uniqueness (30e), as if he were tempting the jury to swat him. Student protesters, in any case, might claim that they are picking up his refutation baton.

Before shifting to address his friends, Socrates concludes the scolding and delivers another surprising takeaway: “So, having divined these things for you who voted against me, I am released” (39d).

I ask students about what “released” could mean here, and they always rise to the occasion. Socrates is released, it seems, from the burdensome confrontation with the powers-that-be, from the rigid legal constraints of a trial, and from the rage-filled conflict that politics regularly generates. He is also released from the need to confront widespread anger and suspicion, a blessing that members of every group today—even straight white males?—may regularly crave. The ultra-mellow tone Socrates immediately presents to his friends, furthermore, strongly suggests that his “vengeance” riff—like everything Plato presents in the Apology?—was completely calculated.[4] And insofar as Socrates’ remarks were intended to deter his friends from conspiring, rioting, or rebelling, they represent a huge accommodation with the drowsy horse (30e).

Socrates initially reassures his friends by invoking his daimon. Although it intervened “always very frequently in all former times” (note the redundancy), warning him “even in quite small matters” when he was “about to do something incorrectly,” the daimon never intervened in any “deed or speech” related to the trial (40a-b). Socrates develops the reassurance by dramatically diminishing the horror of death, an eventuality that remains salient 2400 years later.

He begins by making death into a binary: it is either “like being nothing,” or, “in accordance with the things that are said,” it is some sort of “change and migration of the soul” (40c). Socrates first develops the analogy between death and long dreamless sleep, which would render death “a wondrous gain” (40d). Socrates is still more enthusiastic about the migration alternative. If “all the dead” are present in Hades, “what greater good could there be than this?” (40e). Socrates proceeds to mention 13 individuals—including Minos, Homer, Odysseus, Ajax and Sisyphus, but not Achilles or any Athenian—with whom he would eagerly “associate” (41a-c). The “greatest” benefit, which would bring him “inconceivable happiness,” is this: “I would pass my time examining and searching out among those there—just as I do to those here—who among them is wise, and who supposes he is, but is not” (41b). Tempering the elitism he conveyed by lauding the 13 individuals, Socrates suggests that a “thousand others” are worth mentioning, “both men and women” (41c).

Aspects of Athenian patriarchy surface elsewhere in the Apology, and Socrates seemed to casually convey misogyny at 35b, before the jurors took the first vote. Now that Socrates is “released” from the constraints I suggested above, the “and women” addition is momentous despite its brevity. Female wisdom is still more conspicuous in the Symposium, the Menexenus, and the Republic. When it comes to what makes life worth living, societies impoverish and even cripple themselves if women’s voices are excluded.

The optimism about dying reiterates Socrates’ earlier suggestions that only the ignorant “fear death” (29a). That optimism, alas, is tempered by the obvious exaggeration he conveys about eternal nothingness; recall the urgency of awakening (30e), the urgency of examining (38a), and the daimon’s commitment to keeping Socrates alive (31d). The exhilarating Hades alternative, furthermore, emerges merely from “the things that are said” (40c, 40e) and (unlike the sleep analogy) would have much less credibility in other times and places.[5]

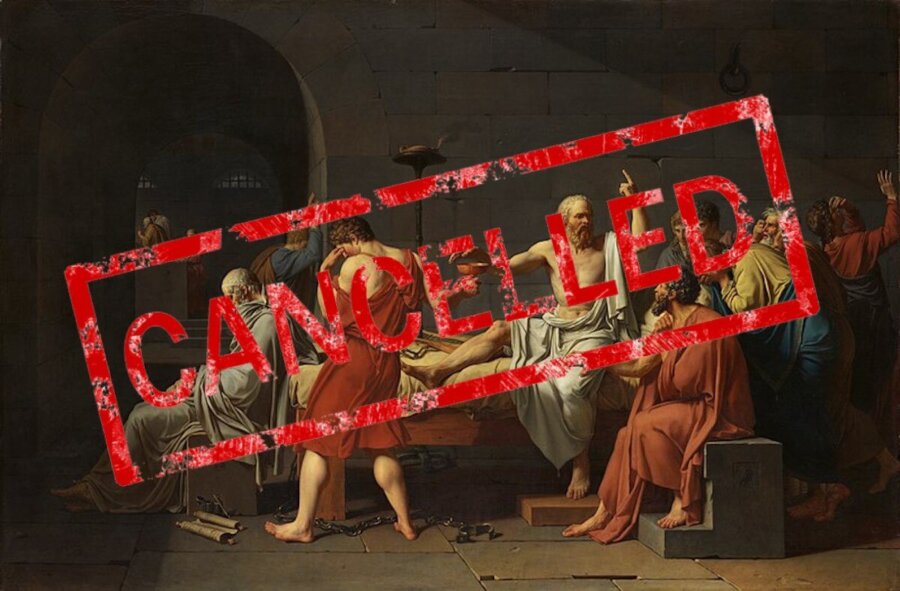

By removing the prospect of afterlife torment, both Apology alternatives can calm fears that remain acute in the 21st century. Socrates’ elation about eternal investigation, moreover, supplies several wholesome lessons. Apart from the thoroughly “inclusive” suggestion that we can learn from every human being, it reiterates the urgency of cherishing processes and journeys as well as results and destinations. In the blissful and danger-free Hades, furthermore, philosophers who quest relentlessly for truth wouldn’t need to “make[s] the weaker speech the stronger” (18b-c) or to concoct noble lies. And even though everyone would be “immortal”—in particular, “those there surely do not kill” examiners (41c)—this Hades retains an element of competitive excitement: regarding the “greatest thing” Socrates would joyfully experience, he would be “examining and searching out” anyone who “supposes” s/he is wise but actually “is not” (41b). Hades would also be a Cancel-Free Zone.

After directing another dramatic pitch for optimism to his friends—“that there is nothing bad for a good man, whether living or dead, and that the gods are not without care for his troubles”—(41c-d), Socrates pivots back to his enemies. Echoing his soothing words about death, Socrates says that he is “not at all angry at those who voted to condemn me and at my accusers,” though they are nonetheless “worthy of blame” for attempting to harm him (41d). In the final amazing twist, Socrates “beg[s]” them to “punish” and “pain” his sons in “the very same way in which I pained you” (41e). Pain, it seems, is essential to life. Here, in any case, Socrates expresses a titanic accommodation by reconciling himself, along with his soon-to-be-fatherless sons, to the community that decided to execute him.

With his very last words, Socrates again situates human ignorance in a religious setting. It is now “time to go away,” him to die and others to live: “Which of us goes to a better thing is unclear to everyone except to the god” (42a).

CONCLUSION: AWAKENINGS, ANCIENT AND MODERN

“Woke” today is one side of a stark binary, and its celebrants are sometimes accused of cultishness. James A. Lindsay pulls no punches: fearing that wokeness is a “totalizing and totalitarian worldview” that could be “installed as the de facto state religion,” Lindsay speculates about using the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses to combat it.[6] Even Aja Romano, a sympathetic and sober analyst, maintains that “woke” has “evolved into a single-word summation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice politics and critical race theory.”

In the Apology Socrates presents multiple binaries: e.g., pathologically lying accusers vs. “the whole truth,” gadfly vs. horse, virtue vs. wealth and reputation,[7] examined vs. unexamined lives, and the two options for death. As I have attempted to sketch, however, the text sometimes subverts them. Most Platonic dialogues combine binaries with forays that muddy the waters. Addressing the differences—including the sometimes dramatic contradictions—among the 30+ dialogues could fill a seven-decade life. And the cacophony mushrooms for anyone who dives into the competing interpretations of Plato that stretch through millennia. Even in the five classroom hours I typically devote to the Apology in my introductory political-philosophy course, we explore more issues than I have addressed above, and we’re always behind even though I regularly cut corners. Although I have taught the Apology in over fifty different quarters, finally, I still learn from my students in every session.

Major interpretive challenges also await someone who dives into any of the following authors: Homer, Hesiod, Herodotus, Sophocles, Thucydides, Aristophanes, Xenophon, Aristotle, Polybius, Cicero, Lucretius, Virgil, Livy, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Augustine, to mention merely the other Greek or Latin authors whom I have scrutinized. Professor Peralta would presumably acknowledge that such authors can be studied productively by people of every nationality, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religion and political ideology.

Even if you deny that some or all of these authors were geniuses whose literary masterpieces illuminate issues that remain salient, you might welcome how they can augment diversity by counteracting “presentism.” The ancient societies, after all, operated for centuries without spawning many of the human-generated menaces we face today, from nuclear weapons, ICBMs, sarin, and mass shootings to Nazism, ISIS, methamphetamines, plastic-infested oceans, the Holocene extinction, and global warming. Although the ancients did not address these challenges, they can help us contemplate the trade-offs that remedies might entail. Regarding authorial diversity, of course, there are troves of women—and non-European men—who are eminently worth reading. Socrates in Hades would doubtless track them down.

There is a binary Socratic version of “Woke” that is urgently needed today—and relatively hard to abuse. No one can deny that, across a huge diversity of circumstances, it is essential that we acknowledge the complexities that surround us—or inhabit our bodies—during each minute we’re alive. Most of them—e.g., stars, planets, and a spectacular array of earthly creatures, from bacteria to blue whales—developed long before our ancestors descended from the trees. Many, however, were created by human beings, e.g., languages and iPhones. Because racists, sexists, and every type of bigot are blind to significant truths, finally, the Socratic woke and the progressive woke can easily unite against them.

In the Apology (and elsewhere) Socrates says many things that appear exaggerated or even doctrinaire, and one could complain similarly about the unnamed philosophers who dominate discussion within Plato’s Laws, Statesman, and Sophist. To appropriate Plato’s most famous allegory, every human society resembles a cave (Republic, 514a – 518b) in which the vast majority of inhabitants are manipulated into accepting views that are profoundly incomplete or distorted. If such blinders are inevitable, every community must regularly draw questioning to a close—and cannot function without slogans, cheerleading, talking points, and inspirational leadership. When implementing a decision, furthermore, we often need to shut down debate as we plow ahead. Our predictive knowledge is rarely certain.

Socratic teaching, with open-ended small-group exercises that encourage students to render judgments and develop comparisons, can combat dogmatism in many different disciplines, and it may be invaluable for studying Plato. Does anyone who assigns the Republic want students to consider expelling everyone older than ten (540e-541a) while launching a radically communist society in which philosopher kings wield absolute power? If nothing else, professors can acknowledge how sharply divided Plato interpreters are on an array of central issues. According to Karl Popper, Myles Burnyeat, Christopher Bobonich, and many other scholars, for example, the Republic elaborates a societal blueprint that Plato hoped would someday be realized. At the other extreme lie scholars such as Allan Bloom, who called it “the greatest critique of political idealism ever written.”[8]

It may be impossible to do justice to the complexity of things, but it is one of the noblest goals anyone can pursue, and intellectual humility will always be invaluable. Few would suggest that contemporary leaders generally exude it, and many worry that it is withering in American higher education. Like the rest of us, including every adult who was ever abused or unjustly maligned, Socrates knew all sorts of important things. But it was never enough.

Notes

[1] Here, and throughout, I am quoting the translation supplied by Thomas G. West and Grace Starry West in Four Texts on Socrates, Revised Edition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press [1988]); the line numbers and letters, developed by Henri Estienne (a.k.a. Stephanus) during the Renaissance, have long been ubiquitous. For comments, suggestions, and corrections regarding my article, I am indebted to William Altman, Zack Blumenfeld, Gabriel Brahm, Murray Dry, James Guest, and Jim Stoner.

[2] Even in the Apology, however, Socrates conveys his interest. Addressing the first-accusers’ charge about “teaching others” (19c), Socrates names Gorgias and two other foreign sophists, who were “able to educate human beings” (19e). He then highlights his curiosity about Evenus of Paros, a sophist who had recently arrived in Athens, though Socrates also conveys doubts about his efficacy. The plot thickens further when Socrates suggests that the expertise needed to educate “human beings” dwarfs what is needed for “colts or calves.” Is there anyone, indeed, who fathoms the “virtue” of “human being and citizen?” (20a-c).

[3] For example, Laches, 194d; Gorgias, 509e; Meno, 77a-78b, 87c-89d; Protagoras, 345d-e, 352c-d, 357d-e, 358b-c, 361b.

[4] Socrates seemed to exaggerate provocatively when asserting that he would speak “at random” in whatever words he “happen[s] upon” (17c). On a regular basis, however, he invites us to assume that he is improvising. After invoking Gorgias et al. (19e) during his lengthy account of the first accusers, for example, he introduces his weighty digression about Evenus with phrasing that is conspicuously casual: “And as for that, there is another man here, from Paros, a wise man, who I perceived was in town; for I happened to meet a man who had paid more money to sophists than all the others, Callias, the son of Hipponicus. . . .” (20a). To students bombarded with tangents by their teachers, Socrates can be highly “relatable.”

[5] In Republic, Gorgias, and Phaedo, Socrates hews more closely to Greek beliefs by including punishment and reward within the afterlife.

[6] To sample my worries about contemporary racial dogmatism, see “How to Be a Better—and Less Fragile—Antiracist.”

[7] Regarding wealth and reputation, consider the concessions at Apology 30b and 35a-b.

[8] The Republic of Plato, Translated, with an Interpretive Essay, by Allan Bloom, Second Edition (New York: Basic Books, 1991), 410. In “Teaching Utopia in Troubled Times,” I invoke the Republic to illuminate Thomas More’s multilayered posture toward communism.