God the Father: Emily Dickinson, Psychoanalysis and the Paternal Relationship

The legacy of eccentricity that nineteenth century poet Emily Dickinson left for the rest of us to unravel after her death in 1886 has proven highly marketable – or, that is, the stuff that academic sleuthy dreams are made of: unrequited love affairs that can only be guessed at after 160-some-odd years; cryptic letters to an unknown recipient found in a desk, never sent; family secrets and animosities; bits and pieces of the past that Dickinsonians still debate as to what goes where on the puzzle board. A quick glance at the vast amount of commentary, criticism, biographical studies, and dramatic or musical interpretations of her life and poetry are a testament to the interest that her name is still able to conjure in academic and literary circles. Whether it is her affinity for the natural world seen in the rich flora and fauna of the Massachusetts landscape she employs for symbolic meaning in her poetry; the speculation over her love life and which lover she was addressing in the “Master” poems; her philosophical musings on immortality; a recurrent death imagery that at times seems to rival (or supersede) the dark Gothic elements of a Tim Burton film – her poems lend a plethora of available subjects through which to interpret Dickinson the woman.

One of the more complex themes of her poetry and life is her perception of religion, particularly her relationship with a deity figure that appears in many of her poems. Dickinson’s attitude towards organized religion is usually quite negative and there has been plenty of discussion as to why. If one takes a more psychoanalytic approach to this topic, however, a far different poet emerges, appearing not simply as a rebellious soul who wished to reject socially-acceptable means of worshiping God but as a woman who, because of a strained relationship with her human father, may have negatively associated the God of her Calvinist upbringing with an unconscious resentment towards the patriarchy her father stood for and the role (or lack thereof) he played in her life. Could Dickinson have unconsciously waged war against her own father that she twisted with her perception of the Christian God?

In Sigmund Freud’s “The Premisses [sic] and Technique of Interpretation”, the theory of dream analysis is explained as:

“[T]he supposition that dreams are psychical phenomena . . . they are products and utterances of the dreamer’s, but utterances that tell us nothing, which we do not understand. Well, what do you do if I make an unintelligible utterance to you? You question me . . . Why should we not do the same thing to the dreamer – question him as to what his dream means?”[i]

If applying this theory to the interpretation of literature, could we not substitute the words dreams and dreamer for the words poems and poet? Freud reasons that the “dreamer knows about his dream” and goes on explain how the individual should be able to eventually discover the meaning of the dream himself.[ii] In this sense, we may look at the work of a poet (dreamer) as waking dreams – the poet’s use of her poems to channel unconscious desires or fears. Still, from the scholar’s perspective, this leaves us with little choice but to essentially create the answer ourselves and question the poet by studying his or her work. We must likewise examine Dickinson’s poetry by asking what deeper, complex issues caused her to produce the themes that she composed. Only then might we “produce the solution” to the poet’s “riddles” if we wish to understand the real nature of Dickinson’s inner life by examining these waking dreams – or in this context, her poetry.[iii]

It is important to first bear in mind the extent to which the religious Puritan heritage of New England was present in the formative years of Dickinson’s development as a poet. Calvinism was a prominent, if not a central figure in Dickinson’s community of Amherst, with family attendance at the First Congregational Church being mandatory. Her father Edward, a famously stern man who took his Puritan philosophy with him into his work in Whig party politics, was highly involved in the administrative duties of the church and the family observed daily religious practices in the Dickinson home. Amherst was a typical small town of the mid-nineteenth century, wherein communities relied upon a common faith and a common building (the church) as a place of social gathering.

Despite Dickinson’s reclusiveness in her later years, as a young woman she was no exception to this standard. Up through her teens and twenties, Dickinson peppered her letters with references to various preachers who came and went in the time that she attended meetings. Whether critiquing a particular sermon as “excellent,” fully admitting that she “did not listen” to another because “I do not respect ‘doctrines’” or expressing her “irritation at ‘his earnest look and gesture, his calls of now today,’” Dickinson seemingly took an interest, even if strictly by familial obligation, in the regular ritual of Sundays, boldly scrutinizing the delivery style of the preacher or simply memorizing “the many Bible verses she remembered hearing at church” which she often modified in her letters, usually in a playful manner.[iv] At other times, she describes her congregational experiences like any irritable adolescent, complaining of coming home from church “very hot, and faded, having witnessed a couple of baptisms, three admissions to church, a Supper of the Lord, and some other minor transactions time fails me to record.”[v] This combination of admiration and disdain is a trademark of Dickinson’s attitudes towards organized worship and as we will see, appears frequently in her poetry in a different form: a desire for God mixed with antipathy.

As early as 1846, at the age of sixteen, Dickinson proclaimed herself as a decided outcast from a complete acceptance of Christianity, declaring that “I have not yet made my peace with God . . . I have perfect confidence in God & his promises & yet . . I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die.”[vi] Although she immediately follows this with a plea for a school friend to “[p]ray . . . that I may yet enter into the kingdom,” and she does convey a general belief in God, the poet’s skeptical demeanor is already becoming firmly established; considering the Puritan community in which she lived, coupled with her status as an unmarried young woman, her outspoken stance on religion is quite extraordinary.[vii] This statement, written in a tone of slight rebellion, and articulating a somewhat tepid conviction in God but still highlighting an ultimate decision of choosing not to give in is a major thematic element that runs through many of her poems:

I never felt at Home – Below –

And in the Handsome Skies

I shall not feel at Home – I know –

I don’t like Paradise –

. . .

If God could make a visit –

Or ever took a Nap –

So not to see us – but they say

Himself – a telescope

Perennial beholds us –

Myself would run away

From Him – and Holy Ghost – and All –

But there’s the “Judgment Day”! [viii]

Here Dickinson is telling us that if it were not for her apparent acknowledgement of an impending day of judgment, she would “run away” and throw off the burden of faith altogether, but due to God’s watchful “telescope” eye on human sin, she acknowledges that she again must stay put and continue to obey, if only out of worry for what would happen if she did not. The framework of this poem is not entirely remarkable and could be described as a forthright example of a young adult struggling with her beliefs and possibly with her identity, never feeling at home, either on earth or in the concept of heaven. Or it may be yet another instance of Dickinson’s sarcasm, an irreverent means of gently satirizing the believer’s anticipation of judgment. Many of Dickinson’s poems that focus on God, whether “questioning the efficacy of his guardianship,” or doubting the relevance of the Bible (“an antique Volume – /Written by faded Men /At the suggestion of Holy Spectres –”), take a derisive, but plainly spoken tone when addressing the legitimacy of the Christian God.[ix]

However, the speaker’s voice in this poem could be interpreted as being distinctly childlike – her simple, uncomplicated phrase “I don’t like Paradise,” and her assertion that she would “run away” from God if she could, seem immature and outrageously self-confident, much in the way a small child may reason away doing something they do not want to do. Dickinson could be reverting a childhood memory, stubbornly wanting to run away from home or “Paradise.” If this Heaven she speaks of is a stand-in for her home life, then who would be the authority there? Is this ever-watching God representative of a human Father?

The closer one reads these poems, the more a pattern begins to emerge. Her quasi-humorous, cynical tone on subjects of heaven and God oftentimes melts into a voice that is subtly vitriolic and other times vividly furious. In other poems, her commentary is more subdued and yet quietly irritated:

Over the fence –

Strawberries – grow –

Over the fence –

I could climb – if I tried, I know –

Berries are nice!

But – if I stained my Apron –

God would certainly scold!

Oh, dear, – I guess if He were a Boy –

He’d – climb – if He could![x]

God is the barrier, not the fence, between the pleasure of berries (or the freedom of personal experience) and herself. If one chooses not to view this poem in a feminist light as might typically be done, her frustration appears only directed at male society from the side; her chief resentment is aimed directly at God, whom she views as “constraining and judging.”[xi] The authoritarian presence that establishes the rules of what she can and cannot do is responsible for her own fear of being found out and scolded, however lightly it may be communicated. She must obey this Heavenly Father and admit to her inability to be free of this parental last word. Dickinson shrugs and accepts this with an “Oh, dear,” leaving the reader with the impression that she may not possess the power to change this situation. Still, one can also sense the internalized anger that is slowly beginning to simmer at the restrictiveness of God’s apparent rules and his denial to her of what she wants or desires.

Again, one can detect Emily Dickinson the child in the voice of the speaker, as opposed to the young woman who is writing these words in the 1850’s and 60’s. She talks of wanting to climb over a fence, something only the school-age Emily would be capable of doing and complains that a boy (not a young man or gentleman, for instance) would be more capable of this feat than herself. Her wishes are nonetheless dashed by God, who would “scold” her if she even attempted such an act as staining her apron in the process of gathering the fruit that lies over the fence. What we must ask ourselves is whether Dickinson is actually conjuring a childhood memory? Was her human father the real barrier here, keeping her back from a seemingly neutral childhood activity whilst her older brother Austin or other boys were allowed to do so? Or was her fear of her father so great that she could not let herself dare to do any kind of activity, however innocuous, that might have incurred his wrath? These poems begin to reveal a far more personalized voice that Dickinson uses to portray the speaker’s inner monologue – which is almost always assumed to be Dickinson herself.

The most intriguing emotional element that shows up repeatedly in these poems on the subject of God is the inevitability of His abandonment of her and a barely-suppressed rage at His withholding of the love that she expects to be paid:

Of Course – I prayed –

And did God care?

He cared as much as on the Air

A Bird – had stamped her foot –

And cried “Give me” –

. . .

‘Twere better Charity

To leave me in the Atom’s Tomb –

Merry, and Nought, and gay, and numb –

Than this smart Misery. [xii]

Dickinson’s ire is unmistakable, especially in analogizing herself in the bird’s place; a small, helpless creature with little defense who quietly – “as on the Air” – makes a gesture that is so minute and soundless that either this mighty power figure she is referencing cannot hear or deliberately chooses not to. Her detachment from God as a result of her prayers failing to be answered or her disappointment at failing to at least be noticed by Him is so profound that she wishes she had never been conceived, as it is better to be “numb” and senseless before the crafting of her eyes and ears in her mother’s womb than experience the “smart” pang of separation from a god whom she wordlessly suggests has betrayed her through a lack of sustenance through prayer. Her emotions are vivid and honest; it is immediately apparent that Dickinson will not hold back when lashing out at this Being who has so injured her emotional state.

However, what can also be seen here is a growing maturity in the speaker’s voice. No longer the child of the two previous poems, the speaker is now reminiscent of an adolescent, having hyperbolic reactions to emotional situations. To her, if would be better to have never been born than endure the hurt she is experiencing. Or could Dickinson be projecting herself onto the bird, stamping her foot in irritation and crying out “Give me!”? By using the analogy of the bird, Dickinson’s indirect message to God in this poem – “Who am I to you? Nothing,” – comes through quite vividly. What remains to be answered is why her feelings are so pronounced towards the God she said she could never fully believe in.

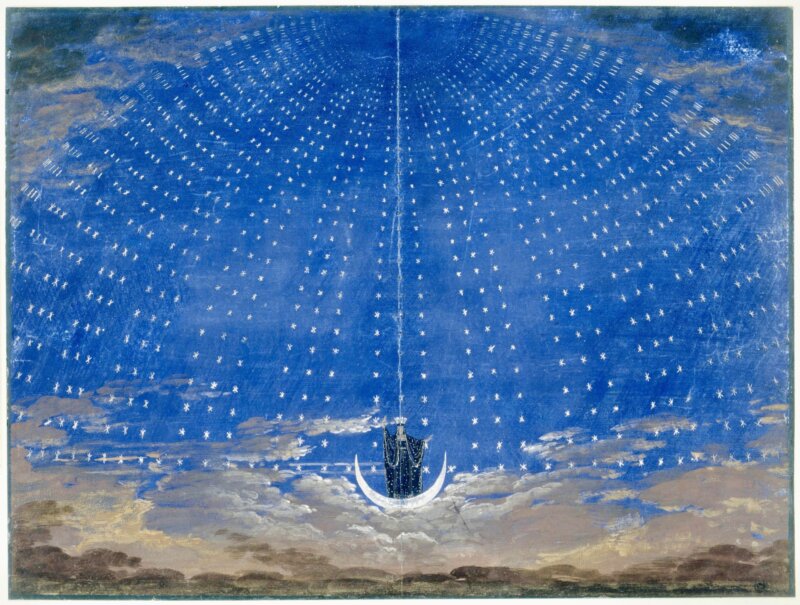

The outstanding quality of these poems is the highly personalized nature of the relationship she is describing, which is directly contrary to the usual blatant disregard she conveys in other poems when describing where exactly she stands in connection with God and her belief in an afterlife: “Is Heaven an exchequer?/They speak of what we owe;/But that negotiation/I’m not a party to.”[xiii] In place of the empty or “voidlike” God that she regards as a figment of humanity’s imagination (she once referred to her family’s morning prayer rituals as nothing more than addressing “an Eclipse . . . they call their ‘Father’”), what appears in select poems instead is a representation of an intentionally cruel “demonic father god” who comes across as being more like a tyrannical despot than anything.[xiv] He is far from being imaginary and indeed comes across as very real in the tone of her poems. This god is rarely, if ever, portrayed as a holy symbol of love and fulfillment or even wisdom; instead he is an emotionally absent, conniving authority figure who only inspires obedience out of sheer terror. He tortures in place of healing and banishes or ignores in place of rescuing.

Far from love the Heavenly Father

Leads the Chosen Child,

Oftener through Realm of Briar

Than the Meadow mild.

Oftener by the Claw of Dragon

Than the Hand of Friend

Guides the Little One predestined

To the Native Land. [xv]

The contrast between the “Little One,” at the center of the poem that conjures up images of a helpless small child and the fierce image of the “Claw of Dragon” is what is so striking when reading this poem. God is a father who takes the sharpest, most unpleasant route in leading the “Little One” towards faith or the promise of being with him in the “Native Land” of Paradise. Claws and thorns, both images suggesting affliction, which bring torment and pain upon the child in Dickinson’s imagination, are inescapable if one is to trust God as the leader, as the lesson in this poem seems to imply that with obedience comes pain.

Again, one may wish to look beyond the surface of the words and try to catch a glimpse of what Dickinson is telling us. Why, for instance, would a small child need to go to Heaven at such a young age? Could the “Native Land” in fact be a symbol for maturity and this parental figure is responsible for leading them there? Does Dickinson portray this rise to adulthood for the “predestined” child (for all must reach adulthood if they live beyond childhood) as a thorny path that is only negative because God (the father) wants it so? Is Dickinson actually mourning a lost childhood or is she regretting a rocky path to her own maturity and blaming a parental figure for this hard road, perhaps?

What exactly prompts Dickinson to use her art form as a cathartic instrument to vent her anger in a “tantrumlike rage” against God, whom she has previously stated she does not believe in?[xvi] If, as she confirms in other poems, her belief in the existence of God is at best shaky or skeptical, scanning “the skies/With a suspicious air” and having “grown shrewder” as the result of experiencing the disappointment of yet another rejection through unanswered prayer, what justifies her resentment that verges on hatred and her constant yearning for love from this spiritual paternal figure?[xvii]

The strained and emotionally distant relationship Dickinson had with her father Edward has been analyzed before in connection with her poetry, however the majority of these studies have mostly focused on oedipal qualities of “psychic incest” or understated, unconscious sexual longing for a detached father.[xviii] What has received less attention is the connection between the bitterness that Dickinson felt towards the figure of God and the mirror feelings that she may have unconsciously held towards her obsessive-compulsive father who represented both patriarchy and the corner stone of religion in her daily life. From an early age, her father had never let them “read anything but the Bible” and if he disapproved of a particular sermon or preacher, he would strictly forbid his children, although they were now young adults, from attending church. [xix]Her father ruled the household “with an autocratic hand,” causing his children to not only fear him in life but even after death, such as Emily’s sister Lavinia who claimed that she still did not marry later in life because “like Emily I feared displeasing father even after he was gone.”[xx] Edward Dickinson was a man not to be trifled with, a figure “whom a whole village feared, in whose appearance was that which terrified.”[xxi] In this way, Dickinson’s poems reveal a symbolic deity that functions as a possible celestial scapegoat for Dickinson’s unresolved emotions with an earthly father.

Within the framework of Freudian interpretation, one may say that Dickinson is actually using both condensation and displacement in these poems, if we are to take the connection to God and human father seriously. Here condensation refers to the merging of two or more elements from a dream into one, or a “situation in a dream” that “seems to be put together out of two or more impressions or experiences.”[xxii] Displacement is the projection of one element’s aspects on to another element or “(emotions) associated with threatening impulses are transferred elsewhere (displaced).”[xxiii] When we examine Dickinson’s poems where her perception of God is undeniably negative, and His actions are regarded as inherently authoritative, we are able to see her use of displacement in projecting her emotions about her father Edward onto God or her merging of her father and God into one symbol in her mind. If the mental image of God that Dickinson was raised with up through her adolescent years was one of remoteness or a figure of wrath that had to be obeyed to achieve positive results, it can then be understandable to see how Dickinson may have projected an aggressively over-bearing father onto this image. We may see Dickinson’s poems as her own waking dreams and whether she is acting upon this consciously or not, the possibility that she merged these two symbols of authority is credible, specifically when we look at the reputation her father held as a less than pleasant force of nature in her life.

Edward Dickinson’s authoritarian rule over his household may not have been atypical of mid-nineteenth century domestic values, but when briefly reviewing Emily’s own descriptions of everyday life with her father and her contemporaries’ observations of the family from an outside perspective, what emerges is an obsessively-controlled family dynamic, with a father at the helm who inspired obedience and loyalty from his children out of his “[o]verpowering . . . hypercritical” presence and his own need for meddling with the details of their lives.[xxiv] Other times, his irascibility caused Emily to be “frightened almost to death” and “‘terrified beyond measure’ at what he might do”, such as on one occasion when a neighbor came to call amidst one of her father’s dark moods – a very revealing statement on her home life.[xxv] Given that Edward Dickinson was characterized as “the absolute embodiment of sedate public authority,” both by his own family and others, it is difficult for us not to see the similarity between him and the God of Dickinson’s poems: highly engaged with his children strictly in terms of asserting a manipulation over their lives, emotionally restrained to the point of abuse, a supreme ruler of a universe, whether literal or figurative of the Dickinson household, and a presence of dominance that was an oxymoron in the sense that he was rarely at home.[xxvi] The poet may have been using the only means she had necessary – an ability to express through verse – to give ventilation to her own complicated feelings towards her father, even if she was unconscious of this.

By all accounts, the relationship between Edward and his daughter seemed respectful and cordial, especially in her later years. However, most of Dickinson’s commentaries or memories of her father reveal quite the opposite, specifically the apprehension and strictness under which she often lived. The fear her father inspired in her through his strong aura of authority is quite apparent from her personal accounts: “I never knew how to tell time by the clock till I was 15,” she recalls. “My father thought he had taught me but I did not understand & I was afraid to say I did not & afraid to ask anyone else lest he should know.”[xxvii] We see that Edward’s presence or demeanor had enough influence on his daughter to cause her to fear admitting fault or making nearly any kind of mistake. Similarly, we find that Dickinson portrays the God of her verse as the all-seeing eye that seems more inclined to scold or punish than forgive. Dickinson’s God does not comfort; he only criticizes. That feeling of rigidity continued into her adolescent years. After a “protracted stay” at a friend’s home one evening that apparently was longer than the usual social call, Dickinson arrived home to find “Father in great agitation…and Mother and [sister] Vinnie in tears, for fear that he would kill me.”[xxviii] While she writes this with yet another dose of subtly sly wit, it does not conceal her father’s evident strict need for control of his family unit, even if in the form of what could pass on the surface as parental worry for one’s children.

If one reads letters from Edward Dickinson to his children, the very exacting, micro-managing advice from this feared parental figure reads more like stage direction than a tender admonition for safety and seems strangely apprehensive, even for nineteenth century standards, and with a tinge of morbidity at that: “When you come home – be careful . . . don’t fall, [k]eep hold of something all the time, till you are safely off [the train] – lest it should start, & throw you down & run over you.”[xxix] Perhaps most telling of all is a message from Dickinson as a young girl to her father by way of a letter, in which her mother writes that Emily “speaks of her Father with much affection. She says she is tired of living without a Father.”[xxx] Edward Dickinson’s work in Congress and his job as a lawyer frequently kept him absent from the family home, as Dickinson claimed that he was “too busy with his Briefs – to notice what we do.”[xxxi] Not unlike the God of her poetry that is spiritually and emotionally absent from her life, Dickinson’s father remained a relatively austere figure who failed to provide his daughter with the warmth she no doubt was craving. Despite this, he certainly provided plenty of rules to adhere to in his absence.

Dickinson’s publisher Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who met her now elderly father in the early 1870’s, described him as “remote” and “speechless – I saw what her life has been,” making sure to take notice of the “excess of tension” that defined Emily’s persona.[xxxii] One wonders whether this anxiety was, as Higginson may have surmised, the result of years locked inside her father’s house and submitting to his authority, even if that choice, especially after she became reclusive in the 1860’s, may have been ultimately hers. Yet, how much of an influence did this supposed tension, possibly stemming from the suppressed feelings she had for her father in such a stifling environment of stress, have on these poems? It is easy to surmise that she may have projected the image of a mortal father on that of an immortal Heavenly Father, as both are figures of authority in the earthly and spiritual sense. Dickinson seemingly rejected one (God) and was called to obey the other (Edward Dickinson), if only out of the respect that was mandatory in that domestic setting.

However, what are we to make of a poet who perceived God as a mere figment, an eclipse, and yet placed such personal and emotional significance on this figment’s rejection or abandonment of her? That the relationship between God and the narrator of the poem is reflective of child/parental dynamics – a father who scolds and keeps watch for misbehavior, that weighs the life of the figurative child in the balance and holds the power of giving or not giving at all to that child – and that it emotionally belies her publicly-proclaimed dismissal of Christian belief in her letters is what brings this issue to the reader’s attention. Dickinson may have possessed enough “intellectual honesty” that “forbade” her from being as emotionally or even philosophically receptive to the Calvinist faith as the majority of her family and neighbors were, but her poetry reveals a darker psychological issue that is at stake, not simply a rational rejection of religious faith.[xxxiii] Dickinson does not so much acknowledge or even dismiss God’s presence as she projects her domestic disappointments and scarred emotions onto this image of God who becomes a stand-in for her own biological father, albeit in an exaggerated fashion.

One may be able to interpret a connection between the practical evidence of Dickinson’s seemingly harsh life with her father and her psychological process of placing her resulting tensions onto her conception of God. The question is whether this reading of her poems is an accurate assessment? Since the speaker in Dickinson’s poems is often interpreted as being her own voice, it is difficult to separate the poet as an individual from the personalized themes that are woven throughout her work. There is always the possibility, however, of misreading Dickinson. We may again turn to Freud for insight into the application of psychoanalytic theory to literature and once more replace “dreams” with “poetry”: “Even if the investigation should teach nothing of the nature of dreams, it may perhaps afford us, from this angle, a little insight into the nature of creative, literary production.”[xxxiv] He is referring here to “story-tellers” or authors who write their characters having dreams within the context of the story.[xxxv] In a similar way, we might see Dickinson as a composer of her own dreams and consider Freud’s words on the importance of the author to psychoanalysis: “Story-tellers are valuable allies, and their testimony is to be rated high, for they usually know many things between heaven and earth that our academic wisdom does not even dream of.”[xxxvi]

While one may not unlock the ultimate mystery of meaning behind her poetry, we may be able to admire Dickinson as a woman who utilized her talent as a means of communicating her inner life through the elegant combination of art and a kind of catharsis of her soul. It is only regrettable that, following this psychoanalytic assessment of her poems, her inability to find healing from her damaged paternal relationship eradicated the all-consuming trust and love she may have easily found in a spiritual relationship with a Heavenly Father who would never have failed her.

Notes

[i] Sigmund Freud, Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, trans. and ed. James Strachey (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989), 53.

[ii] Ibid., 56.

[iii] Ibid., 54.

[iv] Alfred Habegger, My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson (New York: Random House, 2001), 126-127, and

Emily Dickinson, “To Mrs. Joseph Haven”, in Emily Dickinson: Selected Letters, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986), 149.

[v] Dickinson, “To Austin Dickinson”, 51.

[vi] Dickinson, “To Abiah Root”, 9.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Emily Dickinson, “I never felt at Home – Below” No. 413 in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960).

[ix] Wendy Barker, “Emily Dickinson and Poetic Strategy” in The Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson, ed. Wendy Martin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), and

Dickinson, “The Bible is an antique Volume” No. 104.

[x] Dickinson, “Over the fence” No. 251.

[xi] Barker, 80.

[xii] Dickinson, “Of Course – I prayed” No. 376.

[xiii] Dickinson, “Is Heaven a physican?” No. 47

[xiv] Susan Kavaler-Adler, “Emily Dickinson and the Subject of Seclusion,” American Journal of Psychoanalysis 51 (March 1991), 30.

Dickinson, “To T. W. Higginson”, 173.

[xv] Dickinson, “Far from love the heavenly Father” No. 138.

[xvi] Kavaler-Adler, 30.

[xvii] Dickinson, “I meant to have but modest means” No. 476.

[xviii] Kavaler-Adler, 32.

[xix] T.W. Higginson in Emily Dickinson: Selected Letters, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986), 149, and

Habegger, 285.

[xx] Maryanne M. Garbowsky, The House without the Door: A Study of Emily Dickinson and the illness of Agoraphobia (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1989), 50.

[xxi] John Cody, After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson, (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), 58.

[xxii] Dino Felluga, “Modules on Freud: On Repression,” Purdue University, https://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/freud3.html

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Garbowsky, 50.

[xxv] Cody, 58.

[xxvi] Habegger, 257.

[xxvii] T.W. Higginson, 210

[xxviii] Dickinson, “To Austin Dickinson”, 47.

[xxix] Habegger, 176.

[xxx] Ibid., 116.

[xxxi] Dickinson, “To T.W. Higginson,” 173.

[xxxii] Habegger, 524.

[xxxiii] Helen Vendler, Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), 14.

[xxxiv] Sigmund Freud, Delusion and Dream, trans. Helen M. Downey (New York: Moffat, Yard & Co., 1917), Bartleby Books Online, http://www.bartleby.com/287/.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Ibid.