How I Got My Philosophic Theme

As far as I can recall, it was a specific event, leading to a particular experience, that gave me the defining theme of the work I’ve done since then in philosophy.

I’d gone uptown to Columbia University to hear a paper presented by a colleague of my late father. The speaker was a tall man, with a pleasing mane of white hair — an appearance that bespoke maturity and benignity. My father had been instrumental in bringing him to Hunter College of The City University of New York, aware that he wanted to get out of the rather narrowly snobbish, upstate college where he’d taught philosophy previously. Over the next few years, he and his wife had become family friends. They’d visited us in Maine. It never occurred to me not to trust him.

His talk, presented in a seminar setting, was well attended. I knew or recognized a number of the scholars, philosophers and religionists, seated around the long table. I no longer remember the title of his lecture, but I was looking forward to learning whatever he’d come there to teach his audience.

Slowly, as his talk unfolded and gathered steam, it became evident that it had one consistent message: the religion of Biblical Israel was bad and the Judaism based upon it is bad too.

I was quite amazed. In those days, you didn’t talk like that in the big city. Some of the attendees were Jewish scholars, who offered their sputteringly indignant counter-arguments. Their anger did not seem to affect the speaker at all. He maintained an aura of imperturbable and naïve simplicity. Since then, I’ve seen that aura on similar occasions. But that was the first time I saw it in an academic setting.

“Roy,” I finally said, “you knew my parents. You met and esteemed [art historian] Leo Bronstein, our longtime family friend. Leo used to say, ‘Purity is loyalty to origins.’ I feel that what you are saying affects my purity.”

The speaker didn’t seem particularly affected by my input. In fact, in the years that followed, Roy would go on to give more talks, along the same lines, all over town. He became known for it.

As the discussion at Columbia continued, privately I had another thought: You would never have dared to talk that way if my parents were still alive. The cat’s away, you think, so the mice can play. Although there were some follow-up communications between Roy and me, our friendship essentially ended that afternoon.

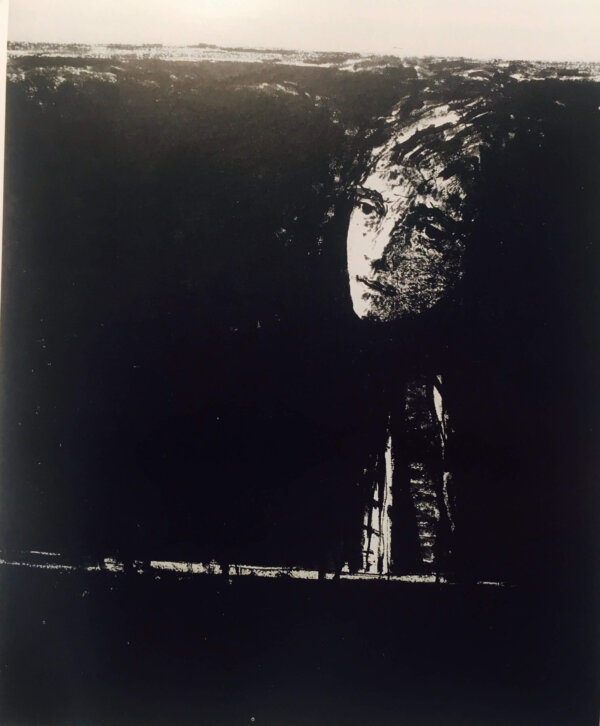

I rode the subway home. Midway, I stopped at one station to change to an eastside-going train. Standing on the dark platform, in the vast, cavernous shadows, I asked the following heartfelt question:

“Lord, what is a Jew?”

Here’s the thought (not one that had occurred to me before) that came to my mind, seemingly in answer:

A Jew is someone who has a passion for God.

“Lord, what is an anti-semite?”

What came into my mind was rather complicated. Not words. It was visual. On that dark subway platform, what I discerned had several features: first, a God situated above the human scene. Below that, the plane of human actors and their actions. The God of that scene was not any sort of impersonal, homogeneous substance. Not “the God of the philosophers.” As a Presence on this scene, God was a Person, or at least personal. The spatial distance between divinity and ourselves was essential to our relationship. The distance was precisely what enabled this God to see what was happening at our level.

To the God of Israel, we are visible.

Inwardly and outwardly.

Visible and accountable.

Here then was the answer to my last question.

An anti-semite is someone who hates the God of Israel.

What, in all our visible doings, particularly merits God’s attention? The answer came: we live stories. Not just shoot-em-up action flicks or soap operas juiced with back-fence gossip. That sort of thing is boring to God. Our serious stories concern the struggles we get in, where good is pitted against evil. Within ourselves, we struggle to discern the difference between the better and the worse alternatives. And, in our situations, it’s a struggle to get on the better side of our possibilities for action.

The life one lives is a true story.

A story with grip isn’t about accidental happenings.

It has a plotline.

It’s about the struggle between good and evil. That’s the plotline interesting to God.

You don’t want to bore God.

Of course, this wasn’t the sole motivator, but it would not surprise me if much that I’ve done since then in philosophy was inspired by that vision in the darkness of a New York subway station. For me, it was a primary datum of experience. It set a theme.

A theme-setting primary datum doesn’t replace the work of discovering where, in the relevant disciplines — philosophy? psychology? political theory? history? anthropology? theology? – the informed discussion stands now. It doesn’t dispose of the requirement to understand the competing views. One still must see whether one’s own view fits inside some extant view, or else modifies it. There is always the possibility that one’s own view must refute some or all of its rivals — or else be refuted by them.

The further task will be to discover which concrete cases are explainable by one’s own view, and where that explanation falls short. If it falls short, is it nevertheless better than its rivals? Or do its competitors shed more light than it does?

It may be that many seekers start with some primary datum of experience that informs their work as its motivating theme. The work cannot end there.

But that is where it starts.