Kant’s Enlightenment

*Note: This was originally a paper presented at the 2023 APSA

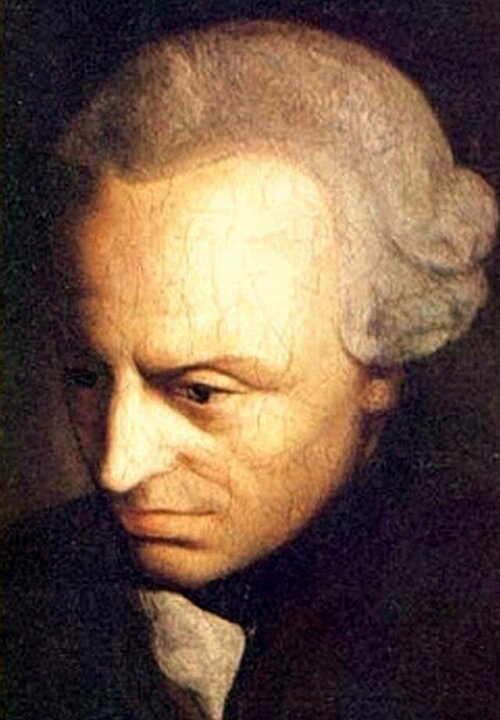

Immanuel Kant is associated with the Enlightenment.[1] Moreover, he self-identified with the Enlightenment and answered the question, “What is Enlightenment?” Kant said it is “man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity,”[2] suggesting he agreed with the Enlightenment’s more full-throated spokesmen who maintained the Enlightenment represented a new beginning for mankind, marked by a radical rejection of what had gone before, namely, classical philosophy and Judeo-Christian revelation—which had formed Western civilization up until Kant in the eighteenth-century— but had become moribund, before the eighteenth-century, to the point of coming under the public attack to which they are still subject.

As in all radical revolutions, primarily intellectual ones, the revolutionaries of the Enlightenment were giddy at the prospects opening up before them as they threw off the ancient constricting faiths in favor of an instrumental rationality which promised to control a reality— Reason replacing God and now enlisted in the service of power rather than truth— that no longer was willing to contemplate it. They drove religious influences from their public squares, quite literally in the French Enlightenment, they embraced the genuine advances being made in the hard sciences and believed the same advances could be made in the human sciences as well, and they placed their hopes in historical progress, not religious salvation. Kant often embraced the hope for continuing historical progress in the moral sense.[3] The modern figure of a rebel– a character who questions all authority and tradition, who seeks, in politics, to constantly radically transform whatever is– emerged from the Enlightenment. The French Revolution, the first of the great modern political revolutions, grew out of the Enlightenment. Recall in 1793, Robespierre turned Notre Dame into the Temple of Reason, an example of how the world became “disenchanted.” Thus, as Gerhart Niemeyer put it, “any thought of mystery was disallowed; there were only things already known and things that eventually would be known.”[4]

The legacy of the Enlightenment was at least ambiguous and much criticism has been leveled at it.[5] The French Revolution itself, in which Kant placed great hope and interest, issued in terror and blood, to his great consternation.

Even apart from his identification with the Enlightenment, Kant is usually thought of, by those who have not read him in any depth and/or may only have heard of his

“reputation,” as a modern philosopher that concerned himself almost exclusively with epistemology. Kant exploded all of the proofs for the existence of God, leaving us with, if anything, only deism, created a very strict ethics based only on duties and rules and denying to man the happiness he craves, and insisted religion be restricted by reason, conceived in the narrowest possible sense.

I want to argue, however, the picture of Kant as an Enlightenment thinker, as otherwise so narrowly drawn, is simply incorrect. In reading Kant, or at least in making that difficult effort, readers realize they are in the presence of perhaps the greatest mind of the last few centuries, and his mind is roiled at the prospect of opening up what will later become known as “modernity.” David Walsh puts it in his ground-breaking treatment of Kant as an existentialist:

. . . Kant was intensely aware of the sense of crisis created by the modern world. Instrumental rationality had begun to devastate the moral landscape. Unlike so many of his contemporaries, however, Kant did not seek refuge in some primal innocence of nature or dream of a lost Arcadia. He remained within the classical and Christian traditions, glimpsing the possibility of carrying them to a higher level of moral truth. This is why his arguments have proved so powerful and so durable in the modern world. Far from departing from Western history, he carried it to a higher level by compelling it to confront its own inner logic.[6]

Kant should not be thought of as an emblematic Enlightenment thinker, rather as the thinker who saved Western civilization from the worst aspects of the Enlightenment by elevating practice over theory in a way that perhaps no thinker— before him— had done. We might say Kant made a double movement relative to the Enlightenment; he embraced its most positive aspects: its emphasis on the importance of human freedom, human rights, personhood, and the corresponding concept of human dignity. Kant reached back before the dawn of the Enlightenment to recapture Western civilization’s ancient emphasis on the moral as the pivot around which everything must turn— ethics thus preceding epistemology, metaphysics, and ontology. As Walsh put it, Kant demonstrates that “Our deepest access to being . . . lies through the moral life. The implication, as Kant saw, is that practical reason illuminates more than theoretical.”[7] If Isaac Newton and the modern scientific revolution convinced us the world of nature, bound by the iron laws of cause and effect, was all that there was, human freedom did not exist– a belief still embedded in twenty-first century culture, but Kant found a way out of that conundrum in proclaiming autonomy as the heart of human dignity.[8]

Kant struggled with, and against, the thought of many of the luminaries of his age. Kant was influenced by Newton, whose new science had eliminated Aristotelian final causality, yet he found a way, in his Third Critique– Critique of Judgment– to reestablish teleology on a modern footing. And Kant was, as he said, “awakened from [his] dogmatic slumber” by David Hume, the great epistemological and moral skeptic of the eighteenth-century, yet he found a way to overcome Humean skepticism in both fields.

Even beyond all of this, one has the sense in reading Kant that one is in the presence of a soul possessed, from the first, by a God whom he cannot know, who he must insist is there, by whom he manages to somehow derive the meaning of it all, the “highest good,” and a God who, above all, even in revelation, insists we all do our duty.

Kant may not be thought of as a theologian, but his work is clearly a philosophical approach to theology. Kant, who penetrated as no one else, had the mysteries of human cognition, ultimately found the most important things shrouded in mystery, as had all the greatest philosophers before him, and extolled faith over knowledge. His absorption in nature, in cause and effect, yielded to the experiences of morality, beauty, the sublime, purpose, and even the possibility of grace. This thirst for knowledge, at last, led Kant to talk about love.

Kant himself is not entirely above critique. In his thought, much is gained and much is recovered, but some important things are also lost. For example:

(1) The term “virtue,” in the classical sense in which we find it in Aristotle and Aquinas, loses its meaning in Kant’s deontological ethics, even though he uses the same term and pens “The Doctrine of Virtue” in The Metaphysics of Morals. Thus, Kant formulates the second of his three fundamental questions in Critique of Pure Reason as “What ought I to do?” (A 805, B 833), rather than, as classical ethicists would have formulated it, “What character ought I to develop?” or “What sort of person should I become?” Kant’s virtuous person is not virtuous in Aristotle’s sense, only continent.

Having said that, I note Kant’s moral philosophy does, in its own way, evidence a concern for the development of character. Furthermore, in beginning Kant’s Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, his first exclusively moral work, he asserts “There is no possibility of thinking of anything at all in the world, or even out of it, which can be regarded as good without qualification, except a good will” (393).[9] Kant acknowledged, at least implicitly, his debt to St. Paul and St. Augustine. And we can say, after all, virtuous and vicious persons are relatively rare, compared to the continent and incontinent categories into which most of us fall.

More on Kant’s moral philosophy later.[10]

(2) Comparing Kant and Aristotle again, we recall Aristotle’s political science consisted primarily of his Ethics and Politics, the former preceding the latter; the relationship between ethics and politics— that we find in Aristotle’s political science— is severed, or at least attenuated, in Kant. In “The Doctrine of Right,” Kant’s principle political work, which appears as the first Part of The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant, one of the developers of modern liberalism and whose thought was to so greatly influence John Rawls two centuries later, stressed freedom, not character development.

Kant defines the “doctrine of right” as “The sum of those laws for which an external law giving is possible” (6:229).[11] The universal principle of right is “any action is right if it can coexist with everyone’s freedom in accordance with a universal law, or if on its maxim the freedom of choice of each can coexist with everyone’s freedom in accordance with a universal law.” (6:230)[12] And the universal law of right is “. . . so act externally [ a categorical imperative] that the free use of your choice can coexist with the freedom of everyone in accordance with a universal law.” (6:231)[13] There is only one “innate right,” and it is the right to freedom. (6:237-238)[14] In contrast, Kant says, “The supreme principle of the doctrine of virtue [which is a categorical imperative] is: act in accordance with a maxim of ends that it can be a universal law for everyone to have.” (6: 395)[15]

Kant drew on the political philosophy of the other great modern liberal philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau to formulate his own. Judging only from his political work, Kant’s philosophical anthropology owed the most to Hobbes, and this kept Kant very sober in his estimation of human nature and his demand for the rule of law. The emphasis in Kant’s politics is on law, which can only govern external actions through external laws, not internal dispositions (those are the subject of virtue). Thus, Kant’s politics is limited primarily to sorting out the concepts of “mine” and “thine.”

While Kant did not say with Aristotle that man is a political animal, he did say that persons have a moral obligation to leave the state of nature (in Kant, an imaginary rather than an historical construct, only an idea of reason) and agree to form the juridical state. Man is political not by nature but by choice. Kant also thought the positive laws to be formulated by that state would have to begin with and be based upon the “natural law” in Kant’s sense of that term, a subject would take a Paper of its own. Positive law in the juridical state is the natural law as positivized, and law consists entirely of a priori principles.[16]

And while one is left at the end of “The Doctrine of Right” wondering how virtue, even in Kant’s attenuated sense, will find its way into his juridical state apart from the natural law hopefully instantiated in the positive laws, one finds an answer in Book Three of Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone. Here, Kant suggests it will be through the influence of religious teaching conveyed by the churches. The public square is not naked in Kant. In fact, in Religion, Kant posits four “polities”:

The juridical state of nature, lending to the juridical-civil state; and

The ethical state of nature, leading to the ethical-civil state.

The ethical-civil state may, and Kant believed should, exist within the juridical-civil state.[17]

The following quotation from Religion reveals Kant’s insistence that the ethical penetrate the political:

As far as we can see . . . the sovereignty of the good principle is attainable, so far as men can work toward it, only through the establishment and spread of a society in accordance with, and for the sake of, the laws of virtue, a society whose task and duty it is rationally to impress these laws in all their scope upon the entire human race. For only thus can we hope for a victory of the good over the evil principle. In addition to prescribing laws to each individual, morally legislative reason also unfurls a banner of virtue as a rallying point for all who love the good, that they may gather beneath it and thus at the very start gain the upper hand over the evil which is attacking them without rest.[18]

Furthermore, recall Kant’s “Doctrine of Right” is itself a moral doctrine, even if it differs from virtue, appearing as it does in The Metaphysics of Morals. Right, in other words, falls under morals and law.

So perhaps Kant’s politics is not that far from Aristotle’s politics after all.

In any event, Kant does give us his own unique way in which to conceive of political liberalism, a liberalism we can certainly recognize in our own country.[19]

(3) Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone is one of Kant’s most fascinating works. In it we find, perhaps to our surprise, Kant was a great student of and much influenced by the New Testament.[20] We also find an inversion of the relationship between nature and grace. Kant cannot seem to bring himself to believe that grace comes before and makes genuine moral action possible. Thus, Christ is not just the archetype of the moral life, but the person who, through his act of atonement, overcomes evil, thereby enacting a “new birth” of the moral life.

(4) It is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine Kant gaining the insights Plato gained in his acceptance of the gifts bestowed through “Divine Madness.”[21] Kant either seems to leave room open for a type of “knowledge” that may come through mystical experience. We are, after all, often more moved by what happens to us, by pathos, than by the conclusions we can arrive at through the use of reason.

I have come primarily to praise Kant, so let me return to the main road.

I wanted to present the story of Kant—something of a drama, really—by focusing not on the Enlightenment but on Kant himself, recognizing that certain contrasts would thereby appear. I had hoped to consider, in summary, each of the principal works of Kant in the chronological order in which they were published: Critique of Pure Reason (1781–1st Ed. and 1787–2nd Ed.), Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Critique of Practical Reason (1788), Critique of Judgment (1790), Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone (1793—1st Ed. and 1794–2nd Ed.), and The Metaphysics of Morals (1797). Alas, that project was misconceived from the start. It would be very difficult, if not impossible, to adequately “summarize” any of Kant’s principle works, much less all of them. In the event, I began with the first, Critique of Pure Reason, but I never got beyond this one work, summarizing it only inadequately.

Fortunately, it is with this work that any study of Kant must begin, and it was— in that work— that Kant anticipated virtually all of his subsequent projects. Critique of Pure Reason is much more than a work of epistemology, and in it, time after time, Kant makes the point I most wish to highlight: in the study of our reason, we may find limits, but these limits are also pointers. And then come the poignant questions, both implicit and explicit in Kant’s work: Why are we pointed beyond our limits, towards what are we pointed, how is it that what we most long to know is what we cannot know, and why are we– in all of nature– the oddest of creatures, possessing this thing called reason, which seems to be both a blessing and a curse?

Eric Voegelin said the classical experience of reason as differentiated in Plato and Aristotle was as “the sensorium of transcendence.”[22] And so the tension of human existence experienced by everyone is reason’s tension toward transcendence. That sense of reason does appear, as we will see, in Kant. Perhaps the tension of human existence is revealed most clearly in Kant in the pairs of categories that structure all of his thought like

Phenomena — Noumena

Nature — Freedom

Knowledge — Faith

a posteriori — a priori

Mechanical laws — Moral laws

Mechanism — Teleology

Positive laws — Natural laws

Science — Religion

Sensible/empirical world — Intelligible world

Physical faculty — Moral faculty

Happiness/inclinations — Duty

Heteronomy — Autonomy

Heteronomous imperatives — Categorical imperatives

No one thinks of Kant as a “mystery writer,” but the most compelling thing about Kant’s writing– and I am not now referring to the well-recognized impenetrability of much of it– is the way in which the mystery of things is revealed in his work, perhaps sometimes with Kant himself being unaware of it. I do not claim to have read all of Kant, be a Kantian scholar, or even have penetrated all of the depths of Critique of Pure Reason, but I merely have become excited by and have formed certain impressions in struggling through Kant’s principle works.[23] And so I turn to the first of them.

CRITIQUE OF PURE REASON

In Kant’s First Critique, or Critique of Pure Reason (1781 (1st ed.) and 1787 (2nd ed.)), Kant makes reason itself the subject of his study, putting reason under the microscope of reason.[24]

What is so striking about Critique– even more than its length, depth, and complexity– is Kant’s radically new epistemology; he tells us how we may obtain knowledge of the phenomena of objects in the realm of nature, or another part of his metaphysics, which also concerns our attempts to know, in which, time and again, how he both approaches and recedes from what we most want to know in the realm of ideas though cannot ever know. Ideas are special concepts that arise out of our knowledge of the realm of nature and the sensible, empirical world, yet seem to point beyond nature to some transcendent realm.[25] The metaphysical ideas of God, human freedom, and the immortality of the soul are the paramount examples. Even if we cannot have knowledge of the objects of such ideas—because these objects are not sensible—the undeniable fact that we all have such ideas must itself be accounted a form of “knowledge,” even if not knowledge in the more proper sense in which Kant uses the term. After all, a directional marker such as a highway sign telling us it is 60 miles to Los Angeles on Interstate Route 10 is no proof that Los Angeles exists, but it is at least highly suggestive.

It is obvious Kant is captivated by the fact that creatures– such as we– should mostly want to know what we cannot know. Lesser so-called philosophers simply claim ideas point to no reality at all, and so become materialists, skeptics, or nihilists. They are, perhaps, afraid of the great mystery our all-too-human lives present us with. Kant, on the other hand, tells us simply that “I . . . had to annul knowledge in order to make room for faith.” (B xxx) Kant thus rejects the atheism and antitheism of the Enlightenment in order to make room for a quite different sort of enlightenment. If the faith that had sustained Western civilization for hundreds of years before the Enlightenment had atrophied to the point where it had come under public attack in the Enlightenment, Kant sought to restore that very same faith, albeit sometimes in rather unorthodox ways. It is something of a paradox that perhaps the greatest philosopher of human knowledge should have been so caught up in the mystery.

Consider in the very last words of the First Critique when Kant refers to human reason’s “desire to know” in the context of his hope “to bring human reason to complete satisfaction in what has always—although thus far in vain—engaged its desire to know.” (A 856, B 884) While, even on his own principles, Kant was wrong to claim human reason could ever be brought to “complete satisfaction.” Sub specie aeternitatis, or the last words of Kant’s First Critique, bring to mind the very first words of Aristotle’s Metaphysics: “All men by nature desire to know.” Philosophy, in its greatest practitioners, transcends the centuries to speak to the most fundamental of human questions. What is it, ultimately, that all of us desire to know? In both Aristotle and Kant, although arriving at the answer to that question in their rather different ways, the answer is the same: All persons desire to know being even unto its divine ground.

My discussion of Critique of Pure Reason below is primarily limited to the topic thus suggested.

Preface to the First Edition

I begin with comments on the Prefaces to the First and Second Editions of Critique. As David Walsh said, “The two prefaces constitute a rich set of reflections on the great work.”[26]

In the very beginning of his Preface to Critique’s First Edition (1781), we find Kant noting there is something mysterious about human reason in that it compels us to confront questions it cannot answer: “Human reason has a peculiar fate in one kind of its cognitions: it is troubled by questions that it cannot dismiss, because they are posed to it by the nature of reason itself, but that it also cannot answer, because they surpass reason’s very ability.” (A vii) Reason, Kant continues, cannot be blamed for this, for it “starts from principles that it cannot avoid using in the course of experience, and that this experience at the same time sufficiently justifies it in using;” however, it “ascends ever higher, to more remote conditions.” (A vii-viii) In this way, reason “becomes aware that . . . since the questions never cease, its task remains forever incomplete.” (Ibid.) Finally, reason, untethered to experience, “plunges into darkness and contradictions,” and enters “The combat arena of these endless conflicts” called “metaphysics.” (Ibid.)

Kant’s project in the First Critique will accordingly be to separate what we can know through our reason from what we cannot know. Thus, it is to overcome both the dogmatists and the skeptics, and, more importantly, the “weariness and utter indifferentism, which is the mother of chaos and night,” resulting from the “endless conflicts.” (A x) “For,” Kant maintains, “it is futile to try to feign indifference concerning inquiries whose object cannot be indifferent to human nature.” (Ibid.) Kant will, as he puts it, answer the “call to reason to take on once again the most difficult of all its tasks—viz., that of self-cognition—and to set up a tribunal that will make reason secure in its rightful claims and will dismiss all baseless pretensions, not by fiat but in accordance with reason’s eternal and immutable laws. This tribunal is none other than the critique of reason itself: the critique of pure reason.” (A xi-xii) Reason, as Kant indicates, calls to itself, and we are forced, through reason, to respond to this call.

As for the results of his efforts, Kant makes the audacious claim “that there should not be a single metaphysical problem that has not been solved here, or for whose solution the key has not at least been provided.” (A xiii) This claim, however, whatever its merits, should not blind us to the great modesty of Kant’s “solution” itself. Recall that the Enlightenment tended to place Reason on the throne formerly occupied by God. Advances in modern science, especially those made by Isaac Newton (1642-1726/27) and others in the Scientific Revolution that preceded and sparked the Enlightenment, seemed to promise infinite progress in the human condition, a conclusion that Auguste Comte (1798-1857) would draw out in the nineteenth-century. Reason, in this sense, would come to seek power rather than truth. Kant’s critique of reason demonstrated, more than anything else, its limits, and thereby also the limits of the Enlightenment.

Preface to the Second Edition

In Kant’s Preface to the Second Edition of Critique (1787), Kant refers to the “Copernican Revolution” in his epistemology; Kant turns from a previous view that all our cognition must conform to objects to his own view that objects must conform to our cognition. (B xvi et seq.) This Revolution, affected by Kant, will, he believes, prove the existence of a real world of nature against the idealists and the skeptics, a world apprehended through the combination of intuition and the understanding, which is the domain of the synthetic a priori categories and concepts that make the cognition of objects possible. Much of the First Critique is given over to an explanation of how cognition in this sense occurs and of how we can have genuine knowledge of objects in the world as phenomena, even though a knowledge of noumena is denied to us. One catches Kant’s own excitement at his discovery in his assertion “that metaphysics will be on the secure path of a science in its first part, viz., the part where it deals with those a priori concepts for which corresponding objects adequate to these concept can be given in experience. For on the changed way of thinking we can quite readily explain how a priori cognition is possible; what is more, we can provide satisfactory proofs for the laws that lie a priori at the basis of nature considered as the sum of objects of experience. Neither of these accomplishments was possible on the kind of procedure used thus far [that is, in classical and medieval epistemology].” (B viii-xix)

Note Kant’s reference here to the “first part” of the science of metaphysics, which is his epistemology directed at the sensible world, or the world we can possess knowledge. There is a “second part” of Kant’s science of “metaphysics.” This is the part that deals with beyond the sensible and our knowledge, and Kant’s respective discussions of the two “parts” may be said to structure the entire First Critique.[27] Kant may have “solved” the problem to the first part of metaphysics, that is, by demonstrating we can have knowledge of the appearances of objects presented to us in intuition and how such knowledge is possible. However, that solution itself demonstrates the “second part” of metaphysics, which, we sense, Kant regards as the more interesting “part” (which cannot be “solved” as much as we would like to see it solved), because it presents matters that transcends an experience we cannot partake in due to limited knowledge that exceed our experience. The second part of metaphysics might also be regarded as an epistemology, albeit one that does not issue in knowledge but in a “rational faith.”

Kant here introduces two concepts that will structure all of his thought: phenomena— the appearances of objects in the sensible, empirical world of which alone we can have knowledge— and noumena— things-in-themselves in the intellectual world that lay behind appearances we can never have knowledge of. Kant says:

On the other hand [that is, in connection with the “second part”], this deduction—provided in the first part of metaphysics—of our power to cognize a priori produces a disturbing result that seems highly detrimental to the whole purpose of metaphysics as dealt with in the second part: viz., that with this power to cognize a priori we shall never be able to go beyond the boundary of possible experience, even though doing so is precisely the most essential concern of this science. Yet this very [situation permits] the experiment that will countercheck the truth of the result that we obtained from the first assessment of our a priori rational cognition: viz., that our rational cognition applies only to appearances, and leaves the thing in itself unrecognized by us, even though inherently actual. For what necessarily impels us to go beyond the boundary of experience and of all appearances is the unconditioned that reason demands in things in themselves; reason—necessarily and quite rightfully—demands this unconditioned for everything conditioned, thus demanding that the series of conditions be completed by means of that unconditioned. (B xix-xx)

This “second part” of metaphysics, about which we cannot have knowledge, concerns what Kant in various places calls the “unconditioned,” “suprasensible,” “supersensible,” or “supernatural.” Kant will later say this is the realm of freedom, of God, and of the immortality of the soul. Kant is led by reason itself, as Aristotle was, to search for the ground of the sensible being of which we can have knowledge in the suprasensible, of which human beings cannot have knowledge. This is, as Kant says, “disturbing.” Being “disturbed,” we long for knowledge— especially— of that which we cannot know, and often, says Kant, try to exceed the boundaries of our possible knowledge (often with bad results).

Kant’s limited concept of reason put him in this dilemma. The dilemma was overcome by the classical and medieval philosophers who took a broader view of reason, who saw reason, as Eric Voegelin characterized it as “the sensorium of transcendence,” an evocative formulation suggesting a form of knowledge in the longing itself. Kant did not give up hope of acquaintance with the suprasensible, the transcendent, escaping the dilemma through a different, his own, route:

Now, once we have denied that speculative reason can make any progress in that realm of the suprasensible, we still have an option available to us. We can try to discover whether perhaps in reason’s practical cognition data can be found that would allow us to determine reason’s transcendent concept of the unconditioned. Perhaps in this way our a priori cognition, though one that is possible only from a practical point of view, would still allow us to get beyond the boundary of all possible experience, as is the wish of metaphysics. Moreover, when we follow this kind of procedure [i.e., the use of practical rather than speculative reason], still speculative reason has at least provided us with room for such an expansion [of our cognition], even if it had to leave that room empty. And hence there is as yet nothing to keep us from filling in that room, if we can, with practical data of reason; indeed, reason summons us to do so. ((B xxi-xxii)

Pure theoretical / speculative reason may not be able to access the suprasensible, but it somehow points us toward it; pure practical reason actually does provide us with an access to it, with a “rational faith” in it even though without a knowledge of it.

Speculative metaphysics thus benefits us negatively “by instructing us that in [using] speculative reason we must never venture beyond the boundary of experience; this instruction is indeed its primary benefit.” (B xxiv) But the benefit becomes positive as well by removing any threat that speculative reason will “venture beyond the boundary of experience . . . [and] displace the pure (practical) use of reason. . . . a use of pure reason which is practical and absolutely necessary (viz., its moral use).” The use that, as we will see, moved Kant to his core. Indeed, we might even say that while Kant worked many years on his First Critique, Critique of Pure Reason, and while Critique is usually considered to be his most important work, he was most interested in it as clearing the ground and paving the way for his moral philosophy that followed its completion. For without the distinction between phenomena and noumena, Kant acknowledges he would not have been able to derive human freedom, requisite for morality, rescuing it from the mechanical laws of cause and effect in nature and leading to the postulates of God and immortality. (B xxv-xxx) As the Third Antinomy of Pure Reason will show (A 444-451, B 472-479), freedom and natural science can both exist side-by-side.

Referring now more explicitly to the moral and the theological opened up by his epistemology, Kant says:

I cannot even assume God, freedom, and immortality, [as I must] for the sake of the necessary practical use of my reason, if I do not at the same time deprive speculative reason of its pretensions to transcendent insight. For in order to reach God, freedom, and immortality, speculative reason must use principles that in fact extend merely to objects of possible experience; and when these principles are nonetheless applied to something that cannot be an object of experience, they actually do always transform it into an appearance, and thus they declare all practical expansion of reason to be impossible. I therefore had to annul knowledge in order to make room for faith. And the true source of all the lack of faith which conflicts with morality—and is always highly dogmatic—is dogmatism in metaphysics, i.e., the prejudice according to which we can make progress in metaphysics without a [prior] critique of pure reason. (B xxix-xxx)

Kant’s famous saying, that he had to annul knowledge in order to make room for faith, may be taken as simply an epigram from the great modern philosopher of the human mind. But any reading of Kant’s principle works will indicate the seriousness of the statement. It might even be said to summarize Kant’s works, especially Critique of Pure Reason. As Kant goes on to say in this Preface, the value of his metaphysics is in “the inestimable advantage of putting an end, for all future time, to all objections against morality and religion. . . . Hence the primary and most important concern of philosophy is to deprive metaphysics, once and for all, of its detrimental influence, by obstructing the source of its errors.” (B xxxi) And here we also think of the third and final questions Kant said united all of his reason’s interest, speculative as well as practical, namely, “What may I hope?” (A 805, B 833) Kant’s hope rested on faith, a “rational faith,” and in some respects, at least, an unorthodox faith.

While pure theoretical / speculative reason can go only so far in its pursuit of knowledge, Kant maintains the limit he has assigned to it affects “only the monopoly of the schools; in no way does it affect the interests of the people.” (B xxxii) The public—for Kant, a most important audience–has never been influenced by what earlier metaphysicians had taken—wrongly, according to Kant—to be their dogmatic “proofs” for the immortality of the soul, the freedom of the will, or the existence of God:

I take it that these proofs have never reached the public and influenced it in that way; nor can they ever be expected to do so, because the common human understanding is unfit for such subtle speculation. Rather, the conviction spreading to the public, insofar as it rests on rational grounds, has had to arise from quite different causes. As regards the soul’s continuance after death, the hope for a future life arose solely from a predisposition discernible to every human being in his [own] nature, viz., the inability ever to be satisfied by what is temporal (and thus is inadequate for the predispositions of his whole vocation). As regards the freedom of the will, the consciousness of freedom arose from nothing but the clear exhibition of duties in their opposition to all claims of the inclinations. Finally, as regards the existence of God, the faith in [the existence of] a wise and great author of the world arose solely from the splendid order, beauty, and provisions manifested everywhere in nature. . . . [While] the arrogant claims of the schools [are thus denied] . . . On the other hand, a more legitimate claim of the speculative philosopher is nonetheless being taken care of here. He remains always the exclusive trustee of a science that is useful to the public without its knowing this: viz., the critique of reason. For that critique can never become popular; nor does it need to be. . . . Solely by means of critique can we cut off, at the very root, materialism, fatalism, atheism, freethinking, lack of faith, fanaticism, and superstition, which can become harmful universally; and finally, also idealism and skepticism, which are dangerous mainly to the schools and cannot easily cross over to the public. If governments do indeed think it proper to occupy themselves with the concerns of scholars, they should promote the freedom for such critique, by which alone the works of reason can be put on a firm footing. (B xxxii-xxxv)

From this long quotation, several observations suggest themselves:

First, as he will stress in his subsequent works of moral philosophy, Kant maintains genuine philosophy first reflects then explains in a deeply penetrating way, beyond the ken of most of us, the common sense of things, what he calls here “the common human understanding.” The youngest child fighting against his inclinations in order to do the right thing is in the grip of the Categorical Imperative. Kant may have been influenced by Thomas Reid, the founder of the “Scottish School of Common Sense” and fierce opponent of Hume, a prominent figure in the “Scottish Enlightenment” (a quite different “Enlightenment” than, for example, the French). Most people are not, thank God, philosophers. Yet the philosopher goes wrong when beginning with anything other than what Kant calls “the common human understanding,” which Kant never belittles. In this sense, Kant’s methodology is the same as Aristotle’s. And Kant is especially hard on thinkers who claim to be philosophers and whose work is intended to undermine “the common human understanding,” especially of the most important things, including those thinkers who traffic in ideas beyond what can be known. This number of which has, if anything, grown exponentially in the centuries since Kant wrote. Whenever Kant might be seen to undermine that understanding, as by his insistence on the limits of what we can know, he is apologetic, explaining his position in such a way that “the common human understanding” is preserved on higher ground. Those familiar with Kant only as an alleged “modern philosopher” may be surprised, even shocked, to see his explicit opposition to an entire range of ideas that bedevil modernity, materialism, fatalism, atheism, freethinking, lack of faith, fanaticism, superstition, and idealism and skepticism that have, long before now, “cross[ed] over to the public.”

Second, in referring to the common “hope for a future life” as having arisen “solely from a predisposition discernible to every human being in his [own] nature, viz., the inability ever to be satisfied by what is temporal (and thus is inadequate for the predispositions of his whole vocation),” Kant reminds us of St. Augustine’s “You made us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.” This is similar to Voegelin’s concept of reason as “the sensorium of the transcendence” noted above, and it is at the core of the thought of the twentieth- century Catholic theologian, Henri de Lubac. It may be the best “proof” for the existence of God there is. It is too bad Kant did not follow up on this, but his concept of reason did not permit it. At least here Kant does not again say it.

Third, Kant here introduces the concept of the human “vocation,” a concept that will appear throughout his work, especially in his moral and religious works. For now, we note the significance of the fact that Kant affirms that each human person has a “vocation,” or to which he or she is in effect “called.” It is a vocation that gives meaning to human life and differentiates it from all other forms of life. To put it in very shorthand, our vocation is to do our duty. Kant’s “vocation” reminds us of Heidegger’s “care.”

Fourth, in referring to “the freedom of the will,” and asserting that “the consciousness of freedom arose from nothing but the clear exhibition of duties in their opposition to all claims of the inclinations,” Kant in effect summarizes his moral philosophy, the principal works of which will follow his First Critique.

Fifth, in referring to the common faith in the existence of God as “a wise and great author of the world” as having arisen “solely from the splendid order, beauty, and provisions manifested everywhere in nature,” Kant already anticipates his Third Critique, Critique of Judgment, in which he explores in depth pleasure and displeasure, beauty and the sublime in nature, and purposiveness in nature. (Indeed, Kant seems to have anticipated all of his future work in the Critique of Pure Reason, which he refers to at one point as a “propaedeutic” (B xliii).)

Sixth, and relative to Kant’s political concerns, which unfortunately have not received the same attention given to the other areas of his thought, Kant here suggests, in a way different from Plato and certainly from Machiavelli, the importance of genuine philosophers to good government. Kant’s Critique is intended to advance “a more legitimate claim of the speculative philosopher,” and we assume Kant is referring to himself. The genuine speculative philosopher “remains always the exclusive trustee of a science that is useful to the public without its knowing this: viz., the critique of reason.” And it is “Solely by means of [this] critique [that we] can . . . cut off, at the very root” the many false ideas and ideologies otherwise brewing in what will become known as “modernity” of “which can become harmful universally” and can become harmful by “crossing over” into public consciousness. Kant says, “If governments do indeed think it proper to occupy themselves with the concerns of scholars, they should promote the freedom for such critique, by which alone the works of reason can be put on a firm footing.” While, as we will see when we consider “The Doctrine of Right” in The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant is a founder of modern liberalism; he is not unconcerned with the relationship among morals, politics, and law, and he voices that concern even in his First Critique. His implicit request made to governments to “promote the freedom for such critique” because it is only thereby that “the works of reason can be put on a firm footing,” was prophetic in much of history subsequent to Kant can be read as the failure to heed that request.

Returning now to the remainder of the Preface to the Second Edition– I note only the importance of footnote 144, in which Kant says that an addition in his Second Edition of the First Critique

. . . consists . . . in a new refutation of psychological idealism, and a strict proof (also, I believe, the only possible proof) of the objective reality of outer intuition. However innocuous idealism may be considered to be (without in fact being so) as regards the essential purposes of metaphysics, there always remains this scandal for philosophy and human reason in general [if we accept idealism]: that we have to accept merely on faith the existence of things outside us (even though they provide us with all the material we have for cognitions, even for those of our inner sense); and that, if it occurs to someone to doubt their existence, we have no satisfactory proof with which to oppose him.

These are problems of idealism and skepticism. If we cannot anchor our reason in which is outside of us, what can we anchor it in?

Kant’s concern was “some obscurity in the expressions I used in that proof” in the First Edition of Critique, and he amends it in the Second Edition. He concludes, “I am conscious with just as much certainty that there are things outside me that have reference to my sense, as I am conscious that I myself exist as determined in time.”

Thus, it is clear Kant’s position is there is a real world of objects outside of us, of the appearances of which we can have knowledge through the combination of our intuition and understanding. Those who might reject Dr. Johnson’s refutation of Berkeley as not “sophisticated” enough—Johnson struck his foot against a large stone, crying, “I refute [Berkeley] thus”—may be more satisfied with Kant’s. Kant’s argument goes beyond merely refuting Berkeley.

What We Can Know; What We Cannot Know

As I mentioned above, Kant’s project in Critique of Pure Reason is to separate what we can know through our pure theoretical / speculative reason from what we cannot know. My principle interest in this Paper is with what we cannot know, but it is necessary to say something first about what we can know in order to make the distinction clear.

What and How We Can Know

We can know the sensible, the empirical, and the realm of nature, and Kant tells us how in the first parts of the First Critique.[28]

Rejecting both the rationalism of Leibniz and the empiricism of Hume but combining aspects of each, Kant tells us we can have knowledge of phenomena, of the appearances of objects, through a combination of our “intuition;” Kant means our sensibility that which “presents” such appearances to us for cognition,[29] with our “understanding.” The understanding is the contribution to knowledge made by our pure theoretical / speculative reason— without which knowledge would not be possible. It also represents what Kant called his “Copernican Revolution.” As Copernicus replaced the earth by the sun as the center of the universe, so Kant replaced the idea that our cognition must conform to objects with the idea that objects must conform to our cognition. Our participation in the acquisition of knowledge is active, not passive. Understanding is part of our pure reason, rational faculty or power, and it is concerned with actively producing knowledge by means of “concepts.” It is the realm of our pure reason in which such concepts exist and through which they operate upon intuition to produce knowledge.

Kant lists the concepts under four “Categories:” quantity, quality, relation, and modality. Three concepts appear under each Category. (A 80, B 106). Kant maintains, “This, then, is the list of all the original pure concepts of synthesis that the understanding contains a priori.” (A 80, B 106) The concepts are the synthetic a priori rules that we ourselves bring to the act of cognition by which we are enabled to understand the manifold of experiences presented to us in intuition, which, without the concepts, would be mere chaos. Only understanding, combined with intuition, makes knowledge possible. For example, Hume argued that we could derive no concept of causation from seeing that one event followed another. In response, Kant maintained that causation is a pure synthetic a priori concept, appearing under the Category of relation. It was Kant’s “discovery” that there could be synthetic, not just analytic, a priori concepts that made his epistemology possible.

Kant thus establishes there is a sensible world we have access to, we can have knowledge of it, and we can think about it.

What We Long to Know, But Cannot Ever Know

We can know phenomena, the appearances of objects we encounter in experience, but we cannot know noumena, the reality “behind” the appearances of objects. Noumena is, however, a broader term– it is not just what is “behind” the appearances of objects we cannot know. We cannot know, as much as we want to do so, what Kant (or his translators) variously refer to as the “suprasensible,” the “supersensible,” the “supernatural,” or the “hyperphysical.” It is in this realm we encounter the “ideas” pure reason itself presents us with like God, freedom, and immortality, but we cannot “know” these concepts, including those we can understand, since they are not objects in the sensible world.

By drawing the distinction between what we can know and what we cannot know, Kant hopes to protect—really, to save—epistemology, metaphysics, and ontology, ultimately validating the knowledge produced by natural science and, in Kant’s own way, the “reality” of what we cannot know. If the two realms are confused, as Kant claims they often have been in the history of philosophy, great damage can be done to both realms.

In any event, the recognition of both uses of reason– to obtain or to attempt to obtain knowledge, one successful and one a failure– overcomes idealism, skepticism, rationalism, and empiricism, “cut[ing] off, at the very root,” the parade of horribles listed in the Preface to the Second Edition.

Table of Contents

As indicated, my principal interest in the body of Critique of Pure Reason are in the parts of it Kant discusses what we long– but cannot– know. There is a great “Why?” question behind this phenomenon: Why should creatures/humans have a desire for a knowledge we cannot have? If Kant’s metaphysics diverges from Aristotle’s, still each can be said to be activated by this question.

In the inevitable struggle involved in wading through the First Critique, frequent repair to a Table of Contents is often necessary. And so below is a Table of Contents, drafted with the principal interest of this Paper in mind.

At the end of the Introduction to the Second Edition, Kant tells us his “science” will be divided into (1) a doctrine of elements, and (2) a doctrine of method, of pure reason. (A 15, B 29) While this is the division of the entire work, the former takes up its greatest bulk.

Transcendental Doctrine of Elements:

Part I. of the “Transcendental Doctrine of Elements” is the “Transcendental Aesthetic,” the subject of which is intuition, the presentation to us of the appearances of objects in the sensible, empirical world of nature, including the two forms of sensible intuition which are synthetic a priori principles of cognition: space and time.

Part II. of the “Transcendental Doctrine of Elements” is the “Transcendental Logic;” its principal division is between Division I., the “Transcendental Analytic,” and Division II., the “Transcendental Dialectic.” Broadly speaking, we can say Kant’s explanation of what we (can) know and how we (can) know it is contained in the “Transcendental Aesthetic” and the “Transcendental Analytic.,” while Kant’s discussion of what we cannot know is contained in the “Transcendental Dialectic.”

Transcendental Doctrine of Method:

This relatively short Section contains four Chapters, “The Discipline of Pure Reason,” “The Canon of Pure Reason,” “The Architectonic of Pure Reason,” and “The History of Pure Reason.”

Introduction

Following the Prefaces, Critique opens with Introductions to both the First and Second Editions.

Kant begins the Introduction to the Second Edition by saying, “There can be no doubt that all our cognition begins with experience.” (B 1) Objects present themselves to us through intuition, and our understanding processes the raw material of these sense impressions into a cognition of objects that is called experience. The understanding can do this because, as we have seen, it is the domain of the synthetic a priori concepts that, combined with intuition, make cognition possible. The concepts in our understanding structure intuitions in such a way that we can obtain knowledge of the manifold of objects (their appearances) presented to us by the world of sense, the empirical world. The “understanding” is Kant’s term for use of pure theoretical / speculative reason that gives us as much knowledge of objects as we can have.

But there is another use of pure theoretical / speculative reason– it is the use that always wants to go beyond the knowledge we can have through the combination of intuition and understanding. Kant refers to it also at the beginning of the Introduction by saying: “Much more significant yet than all the preceding [discussion of the first use of pure reason] is the fact that there are certain cognitions that [not only extend to but] even leave the realm of all possible experiences. These cognitions, by means of concepts to which no corresponding object can be given in experience at all, appear to expand the range of our judgments beyond all bounds of experience.” (A 2-3, B 6) It is these cognitions

which go beyond the world of sense, where experience cannot provide us with any guide or correction, [in which] reside our reason’s inquiries. We regard these inquiries as far superior in importance, and their final aim as much more sublime, than anything that our understanding can learn in the realm of appearances. Indeed, we would sooner dare anything, even at the risk of error, than give up such treasured inquiries [into the unavoidable problems of reason], whether on the ground that they are precarious somehow, or from disdain and indifference. These unavoidable problems of reason themselves are God, freedom, and immortality. But the science whose final aim, involving the science’s entire apparatus, is in fact directed solely at solving these problems is called metaphysics. Initially, the procedure of metaphysics is dogmatic; i.e., [metaphysics], without first examining whether reason is capable or incapable of so great an enterprise, confidently undertakes to carry it out. (A 3, B 6-7)

Here, Kant appears to limit “metaphysics” to this second use of pure theoretical / speculative reason, and we see Kant, whose usual writing style is metaphysically dry, can be eloquent when he wants to be. Again we note the similarity of Kant’s concept of metaphysics to Aristotle’s, and while Kant does not use the word “wonder,” as Aristotle did, he might have. We note as well that Kant, in the very Introduction to his First Critique, refers to the subjects that will occupy virtually all of his work subsequent to the First Critique– God, freedom, and immortality.

Only the first use of pure theoretical / speculative reason, in which we find such reason in the synthetic a priori concepts of the understanding, can issue in knowledge (when combined with intuition). The second use of pure theoretical / speculative reason cannot issue in knowledge, and Kant will go on to harshly criticize those “dogmatic” metaphysicians who think it can[30] and find “proof” of God, freedom, and immortality are not in pure theoretical / speculative reason but are found only in pure practical reason. As Kant will show, synthetic a priori judgments that go beyond all possible experience cannot be justified theoretically / speculatively at all, though they may still be justified in the practical / moral realm.

The “pure reason” Kant has in mind in his Critique of this subject is the realm of the synthetic a priori concepts, rules, principles, and ideas existing in our minds of which themselves Kant wants to have knowledge.

In Chapter V. of the Introduction to the Second Edition, Kant maintained that all theoretical sciences of reason contain synthetic a priori judgments as principles, including “Mathematical judgment are one and all synthetic” (B 14), “Natural science (physica) contains synthetic a priori judgments as principles” (B 17), and “Metaphysics is to contain synthetic a priori cognitions” (B 18)– note the present tense relative to mathematics and natural science, and the future tense relative to metaphysics. Kant’s discussion of metaphysics here is confusing, as best, but he appears to be using metaphysics to mean the science of the supersensible, and to suggest that, through his work, metaphysics will attain the same status as mathematics and natural science relative to the possession of synthetic a priori cognitions.

In Chapter VI. of the same Introduction, entitled “The General Problem of Pure Reason,” Kant, in attempting to “bring a multitude of inquiries under the formula of a single problem,” says, “Now the proper problem of pure reason is contained in this question: “How are synthetic judgments possible a priori?” (B 19). Kant argues that metaphysics, to date, has “remained in such a shaky state of uncertainty and contradictions” because “this problem, and perhaps even the distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments, has not previously occurred to anyone. Whether metaphysics stands or falls depends on the solution of this problem, or on an adequate proof that the possibility which metaphysics demands to see explained does not exist at all.” (Ibid.) Kant will conclude that metaphysics stands because his “Copernican Revolution” revealed that and how synthetic a priori judgments are possible.

Hearkening back to Chapter V., Kant raises the related questions of “How is pure mathematics possible?,” and “How is pure natural science possible?” (B 20) He answers by saying that in solving the problem of “How are synthetic judgments possible a priori?,” he has answered these questions as well. (B 20-21) That leaves, we recall from Chapter V., the question, “How is pure metaphysics possible?” But Kant, who continues to use “metaphysics” to refer to the suprasensible realm now, does not ask this question.

As he indicated in his discussions in Chapter V. of the theoretical sciences of mathematics, natural science, and metaphysics. Metaphysics is different from mathematics, because it presents us with entirely pure concepts; natural science presents us with objects we can cognize through the combination of intuition and understanding. As he further indicated in Chapter V., in contrast with mathematics and natural science, metaphysics is to contain synthetic a priori cognitions, that is, it does not contain them now, given that we are only at the Introduction to Kant’s great work. Continuing to contrast metaphysics with mathematics and natural science, Kant says:

As regards metaphysics, however, there are grounds on which everyone must doubt its possibility: its progress thus far has been poor; and thus far not a single metaphysics has been put forth of which we can say, as far as the essential purpose of metaphysics is concerned, that it is actually at hand.

Yet in a certain sense this kind of cognition must likewise be regarded as given; and although metaphysics is not actual as a science, yet it is actual as a natural predisposition (i.e., as a metaphysica naturalis). For human reason, impelled by its own need rather than moved by the mere vanity of gaining a lot of knowledge, proceeds irresistibly to such questions as cannot be answered by any experiential use of reason and any principles taken from such use. And thus all human beings, once their reason has expanded to [the point where it can] speculate, actually have always had in them, and always will have in them, some metaphysics. (B 21)

And so we hear again, over the centuries, the voice of Aristotle raised at the very beginning of Western metaphysics: “All men,” not just philosophers, “by nature desire to know.” We are all, from the loftiest college philosophy professor to the lowliest so-called “street person,” by nature, metaphysicians, to greater or lesser extents. Nature, with an irresistible force, predisposes us thus. And we are left again with wonder that we are such creatures that can have such a desire, a wonder that perhaps can only be resolved by revelation, by the Biblical assertion that we are all made in the image and likeness of God in that we have reason and free will. Genesis 1:26.

Instead of asking the question, “How is pure metaphysics possible?,” Kant asks the question, “How is metaphysics as a natural predisposition possible?, i.e., how, from the nature of universal human reason, do the questions arise that pure reason poses to itself and is impelled, by its own need, to answer as best it can?” (B21-22)

However, given that “Thus far . . . all attempts to answer these natural questions—e.g., whether the world has a beginning or has been there from eternity, etc.—have met with unavoidable contradictions” (B 22), we must go beyond our “natural predisposition,” and Kant’s vocation is to show us the way. “Hence,” he says,

we cannot settle for our mere natural predisposition for metaphysics, i.e., our pure power of reason itself, even though some metaphysics or other (whichever it might be) always arises from it. Rather, it must be possible, by means of this predisposition, to attain certainty either concerning our knowledge or lack of knowledge of the objects [of metaphysics], i.e., either concerning a decision about the objects that its questions deal with, or certainty concerning the ability or inability of reason to make judgments about these objects. In other words, it must be possible to expand our pure reason in a reliable way, or to set for it limits that are determinate and safe. (Ibid.)

“This last question,” Kant goes on, which flows from the problem as to how, in general, synthetic judgments are possible a priori, “may rightly be stated thus: How is metaphysics as science possible?” (Ibid.) Again, we may have been expecting the questions, “How is pure metaphysics possible?,” but Kant does not ask it. Perhaps in the case of metaphysics the questions, “How is metaphysics as science possible?” and “How is pure metaphysics possible?” are the same question, and they are resolved in the proposition left open in Chapter V. by completing it as follows: “Metaphysics does contain synthetic a priori cognitions.” After all, Kant does go on to assert metaphysics, as science, is possible, and to demonstrate it is possible as science, and as pure, because it contains synthetic a priori cognitions. And we might say the rest of Critique of Pure Reason is devoted to that demonstration. Further, it seems to me that, in that work, Kant both expands pure reason in a reliable way and sets for it limits that are determinate and safe, in effect doing the one by also doing the other, but I am not sure about that.

In any event, following the question, “How is metaphysics as science possible?,” Kant continues:

Ultimately, therefore, critique of pure reason leads necessarily to science; the dogmatic use of pure reason without critique, on the other hand, to baseless assertions that can always be opposed by others that seem equally plausible, and hence to skepticism.

This science, moreover, cannot be overly, forbiddingly voluminous. For it deals not with objects of reason, which are infinitely diverse, but merely with [reason] itself. [Here reason] deals with problems that issue entirely from its own womb; they are posed to it not by the nature of things distinct from it, but by its own nature. And thus, once it has become completely acquainted with its own ability regarding the objects that it may encounter in experience, reason must find it easy to determine, completely and safely, the range and the bounds of its use [when] attempted beyond all bounds of experience. (B 22-23)

Kant’s great worry, that dogmatism in metaphysics leads only to skepticism, that is, to the denial of any reality behind the ideas of God, freedom, and immortality, and so ultimately away from “rational belief,” is suggested in the beginning of the next paragraph, which completes Chapter VI. of the Introduction:

Hence all attempts that have been made thus far to bring a metaphysics about dogmatically can and must be regarded as if they had never occurred. For whatever is analytic in one metaphysics or another, i.e., is mere dissection of the concepts residing a priori in our reason, is only a prearrangement for metaphysics proper, and is not yet its purpose at all. That purpose is to expand our a priori cognition synthetically, and for this purpose the dissection of reason’s a priori concepts is useless. For it shows merely what is contained in these concepts; it does not show how we arrive at such concepts a priori, so that we could then also determine the valid use of such concepts in regard to the objects of all cognition generally. Nor do we need much self-denial to give up all these claims [of dogmatic metaphysics]; for every metaphysics put forth thus far [including Aristotle’s?] has long since been deprived of its reputation by the fact that it gave rise to undeniable, and in the dogmatic procedure indeed unavoidable, contradictions of reason with itself. A different treatment, completely opposite to the one used thus far, must be given to metaphysics–a science, indispensable to human reason, whose every new shoot can indeed be lopped off but whose root cannot be eradicated. We shall need more perseverance in order to keep from being deterred–either from within by the difficulty of this science or from without by people’s resistance to it–from thus finally bringing it to a prosperous and fruitful growth. (B 23-24)

Kant, like Voegelin and other philosophers of consciousness after Kant, thus focused his principal attack on dogmatism, which had led in the realm of metaphysics, as it leads in other realms, including the spiritual, to skepticism, in the throes of which reason may completely slipped its moorings and issue in all sorts of things having little or no relationship to reality at all. One thinks here of the mass political ideologies arising in the centuries after Kant might have been prevented by careful attention to Kant.

At the beginning of Chapter VII., the last Chapter of the Introduction, Kant says: “From all of the above we arrive at the idea of a special science that may be called the critique of pure reason. For reason is the power that provides us with the principles of a priori cognition. Hence pure reason is reason that contains the principles for cognizing something absolutely a priori.” (A 10-11, B 24-25) A critique of pure reason, which must limit itself to the study of reason, is really only a propaedeutic to the system of pure reason. “For such a critique would serve only to purify our reason, not to expand it, and would keep our reason free from errors, which is a very great gain already. I call transcendental all cognition that deals not so much with objects as rather with our way of cognizing objects in general insofar as that way of cognizing is to be possible a priori. A system of such concepts would be called transcendental philosophy.” (A 11-12, B 25)

Kant distinguishes a critique of pure reason and a transcendental philosophy. The former is limited to a consideration of synthetic a priori cognition, and the latter also includes analytic a priori cognition.[31] Kant will limit himself to the former. And he has a “foremost goal” in dividing the science he is proposing:

no concepts whatever containing anything empirical must enter into this science; or, differently put, the goal is that the a priori cognition in it be completely pure.[32] Hence, although the supreme principles and basic concepts of morality are a priori cognitions, they still do not belong in transcendental philosophy. For they do of necessity also bring [empirical concepts] into the formulation of the system of pure morality: viz., the concepts of pleasure and displeasure, of desires and inclinations, etc., all of which are of empirical origin. Although the supreme principles and basic concepts of morality do not lay these empirical concepts themselves at the basis of their precepts, they must still bring in such pleasure and displeasure, desires and inclinations, etc. in [formulating] the concept of duty: viz., as an obstacle to be overcome, or as a stimulus that is not to be turned into a motive. Hence transcendental philosophy is a philosophy of merely speculative pure reason. For everything practical, insofar as it contains incentives, refers to feelings, and these belong to the empirical sources of cognition. (A 14-15, B 28-29)

The critique of pure theoretical / speculative reason is devoted to an analysis of the synthetic a priori concepts of the understanding, by which we cognize objects in nature presented to us in intuition. Pure practical reason, the realm of Kant’s moral philosophy, and of God, freedom, and immortality, which has its own synthetic a priori concepts, and which is the subject of Kant’s Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, the Critique of Practical Reason, and The Metaphysics of Morals, is rather sharply distinguished from pure theoretical / speculative reason, which is the subject of the Critique of Pure Reason.

In proposing to divide the science he is setting forth in terms of the general viewpoint of a system as such into a doctrine of elements and a doctrine of method, of pure reason. Each of which will be further subdivided, and Kant concludes the Introduction as follows:

Each of these two main parts would be subdivided; but the bases on which that subdivision would be made cannot yet be set forth here. Only this much seems to be needed here by way of introduction or advance notice: Human cognition has two stems, viz., sensibility and understanding, which perhaps spring from a common root, though one unknown to us. Through sensibility objects are given to us; through understanding they are thought. Now if sensibility were to contain a priori presentations constituting the condition under which objects are given to us, it would to that extent belong to transcendental philosophy. And since the conditions under which alone the objects of human cognition are given to us precede the conditions under which these objects are thought, the transcendental doctrine of sense would have to belong to the first part of the science of elements. (A 15-16, B 29-30)

“Transcendental Aesthetic”

And so Kant begins the “Transcendental Doctrine of Elements” with Part I., the “Transcendental Aesthetic,” which concerns intuition, and it’s a priori presentations of space and time. We will not consider it here.

“Transcendental Logic”—“Introduction”

Part II. of the “Transcendental Doctrine of Elements” is the “Transcendental Logic.” It contains two “Divisions:” Division I., the “Transcendental Analytic,” and Division II., the “Transcendental Dialectic.” Broadly speaking, the “Transcendental Analytic” is about understanding, and the “Transcendental Dialectic” is about “reason.”

In the “Introduction” to the “Transcendental Logic,” entitled “Idea of a Transcendental Logic,” Kant famously says,

Without sensibility no object would be given to us; and without understanding no object would be thought. Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind. Hence it is just as necessary that we make our concepts sensible (i.e., that we add the object to them in intuition) as it is necessary that we make our intuitions understandable (i.e., that we bring them under concepts). Moreover, this capacity and this ability cannot exchange their functions. The understanding cannot intuit anything, and the senses cannot think anything. Only from their union can cognition arise. (A 51-52, B 75-76)

Knowledge depends on the full cooperation of sensibility (or intuition) and understanding– therefore what is beyond sensibility is beyond knowledge.

The science of the rules of sensibility as such is aesthetic,[33] and the science of the rules of the understanding as such is logic. (A 52, B 76) Of the various kinds of logic, “Transcendental Logic” is the logic that “deals merely with the laws of understanding and of reason [hence the two Divisions]; it does so only insofar as this logic is referred a priori to objects—unlike general logic, which is referred indiscriminately to empirical as well as pure rational cognitions.” (A 57, B 81-82) In the “Transcendental Aesthetic,” Kant isolated sensibility for examination, and in the “Transcendental Logic,” he isolates the understanding and reason for examination.

Kant calls the “Transcendental Analytic” “a logic of truth” (A 62-63, B 87), and the “Transcendental Dialectic” “the logic of illusion” (A 61, B 85-86). Relative to this distinction, Kant warns us of

great enticement and temptation to employ these pure cognitions of understanding and these principles by themselves, and to do so even beyond the bounds of experience, even though only experience can provide us with the matter (objects) to which those pure concepts of understanding can be applied. As a consequence, the understanding runs the risk that, by idly engaging in subtle reasoning, it will put the merely formal principles of pure understanding to a material use, and will make judgments indiscriminately even about objects that are not given, or indeed about objects that perhaps cannot be given in any way at all. Properly, then, transcendental analytic should be only a canon for judging the empirical use. Hence we misuse transcendental analytic if we accept it as the organon of a universal and unlimited use, and if with pure understanding alone we venture to judge, assert, and decide anything synthetically about objects as such. Hence the use of pure understanding would then be dialectical. Therefore the second part of transcendental logic must be a critique of this dialectical illusion, and is called transcendental dialectic. It is to be regarded not as an art of dogmatically creating such illusion (an art that is unfortunately quite prevalent in diverse cases of metaphysical jugglery), but as a critique of understanding and reason as regards their hyperphysical use. We need such a critique in order to uncover the deceptive illusion in the baseless pretensions of understanding and reason; and we need it in order to downgrade reason’s claim that it discovers and expands [cognition]—which it supposedly accomplishes by merely using transcendental principles—[to the claim that it] merely judges pure understanding and guards it against sophistical deceptions. (A 63-64, B 87-88)

In our passionate seeking to cognize the non-material, purely intellectual “ideas” that “reason” inevitably presents us with, such as God, freedom, and immortality of the soul, which “entice and tempt” us far beyond the objects presented to us in intuition, we are tempted to use the “concepts” of the “understanding” which do, in combination with intuition, permit cognition of the “objects” of the empirical, sensible world, forgetting that cognition of such “ideas” is not possible through the use of pure theoretical / speculative reason. We cannot go beyond the bounds of experience in this way, in effect forgetting or failing or refusing to realize that “only experience can provide us with the matter (objects) to which those pure concepts of understanding can be applied.” If we try to do that, as so many metaphysicians have in the past, we risk establishing a dogmatism which, because it is based on a logical fallacy, will undermine all possible cognition. As we will see in the “Transcendental Dialectic,” we are not without a way to cognize the “ideas” of “reason,” and that way is through pure reason, but only of the “practical” variety. And so, while Kant properly says here that his critique is “need[ed] . . . in order to downgrade reason’s claim that it discovers and expands [cognition] . . . [to the claim that it] merely judges pure understanding and guards it against sophistical deceptions,” that is not the end of reason’s story.

“Transcendental Logic”—Division I. The “Transcendental Analytic”

We will not consider the “Transcendental Analytic,” which concerns the synthetic a priori concepts of the understanding, here. Instead we will move on to consider the “Transcendental Dialectic,” having been warned by Kant it can be the source of metaphysical error. What we will also find in it is the luminosity of the ideas thrown to us by pure reason.

“Transcendental Logic”—Division II. The “Transcendental Dialectic”

Division II. of the “Transcendental Logic” is the “Transcendental Dialectic.” Following an “Introduction” and a Book I., “On the Concepts of Pure Reason,” Book II. contains three Chapters entitled “On the Paralogisms of Pure Reason,” “The Antinomy of Pure Reason,” and “The Ideal of Pure Reason.”

Introduction

As indicated, while the “Transcendental Analytic” focused on the understanding and its concepts which, together with intuition, make cognition of the objects of the empirical, sensible world possible, the “Transcendental Dialectic” focuses on reason and its ideas, and warns against all attempts to cognize such ideas through the methodology set out in the “Transcendental Analytic.” In the “Transcendental Dialectic” Kant will show, in Paralogisms, Antinomies, and the Ideal of Pure Reason, how reason may overstep its boundaries in attempting to free the understanding from the limit it has to experience, leading to what Kant calls “dogmatism”[34] and “Transcendental Illusion.”[35]

The “Transcendental Dialectic” offers a justified discipline to reason, and considerations of it often stop there. “Transcendental Dialectic” is one of the most important parts of Critique of Pure Reason, because there Kant discusses in a thorough-going way the “ideas” of “reason,” which we cannot cognize through the understanding. As he indicates several times in Critique, it captures our interest much more than do the “objects” we can actually cognize through the “understanding.” How remarkable it is that creatures such as ourselves should even seek to know, above all other possible matters, what we cannot ever know, that we cannot avoid the “transcendental illusion” (A 297, B 353-354)! At the end of Chapter I, “On Transcendental Illusion,” of the “Introduction” to the “Transcendental Dialectic,” Kant stresses the staying power of the “Transcendental Illusion”:

Hence the transcendental dialectic will settle for uncovering the illusion of transcendent judgments, and for simultaneously keeping it from deceiving us. But that illusion should even vanish as well (as does logical illusion) and cease to be an illusion–this the transcendental dialectic can never accomplish. For here we are dealing with a natural and unavoidable illusion that itself rests on subjective principles and foists them on us as objective ones, whereas a logical dialectic in resolving fallacious inferences deals only with a mistake in the compliance with principles, or with an artificial illusion created in imitating such inferences. Hence there is a natural and unavoidable dialectic of pure reason. This dialectic is not one in which a bungler might become entangled on his own through lack of knowledge, or one that some sophist has devised artificially in order to confuse reasonable people. It is, rather, a dialectic that attaches to human reason unpreventably and that, even after we have uncovered this deception, still will not stop hoodwinking and thrusting reason incessantly into momentary aberrations that always need to be removed. (A 297-298, B 354-355)