Kill Ill: Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit

Friedrich Dürrenmatt, wrote The Visit[1] (Der Besuch der alten Dame) in 1956. Dürrenmatt is a twentieth century Swiss playwright (1921-1990) who gets mentioned alongside Beckett, Camus, Sartre, and Brecht. Like them, he is interested in examining moral dilemmas with wider social import, bearing a tendency toward the nihilistic, and a “you just can’t win” attitude, such as can be seen in Sartre’s Men Without Shadows (Morts sans Sépultures), No Exit (Huis Clos), and Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. The Visit is overtly “philosophical” in the manner of existentialism: a despairing morality play.[2]

In The Visit, Claire Zachanassian has been wronged by the town of Guellen (Liquid manure town) located “somewhere in Central Europe,” and Alfred Ill, and she has returned forty-five years later to exact her revenge.[3] Claire and Ill were lovers. Claire became pregnant but Ill wanted to marry someone else who had a shop and money. He bribed two witnesses to say that they had also slept with Claire. Claire’s paternity suit is thrown out and the town sniggers as she is forced to leave town for the life of a prostitute. In this capacity, she meets and marries a billionaire and a succession of other husbands until she is the richest woman in the world. In her capacity as such, she represents an all-powerful monster capable of bending the world to her wishes. A grotesque figure, two of her limbs have been replaced by protheses; an ivory arm and a leg. At one point Ill asks, “Claire, is everything about you artificial?” She uses a lorgnette. These spectacles with a handle held away from the face, suggests she has her own very particular outlook on things and creates a distance between her and the people she observes. Claire has returned to Guellen with a macabre retinue who include the false witnesses whom she has castrated and blinded, the judge who presided over her case and who is now her butler, a black panther, two bodyguards, her husband number VII, and a coffin.

Claire’s offer to the townspeople of Guellen, to give them a billion[4] if someone kills Ill, is initially met with horror and is rejected. But, the townspeople are tempted by the billion and this temptation is made stronger by the fact that Claire has economically destroyed the town by buying and then closing its factories. The rest of the play involves the town’s moral corruption, and Ill’s attempts to find a defender and to escape his fate. As a store owner, Ill sees the townsfolk begin to buy more and more expensive things; placing them all on credit. It becomes obvious that their only way of paying for these items will be to accept Claire’s offer and to kill Ill.

Claire Zachanassian resembles Medea, one of the most terrifying and morally reprehensible characters from Greek tragedy, who murdered her children when Jason, the father, abandons her for another woman for political purposes: a vengeful woman who takes extreme actions to punish her lover. But mostly, Claire represents unstoppable Fate; personifying the social forces that grind up the sacrificial victim. The Three Fates were all female; Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. She who spun the thread of life: she who determined one’s lot in life: and she who decided when to end one’s life, cutting the thread with her golden sheers. Schoolmaster says she is “like one of the Fates; she made me think of an avenging Greek goddess. Her name shouldn’t be Claire, it should be Clotho. I could suspect her of spinning destiny’s web herself.”[5] Her semi-divine status is reinforced by the fact that she is “unkillable.”[6] Scapegoats are accused of causing utter social disintegration; something of which no individual acting alone can achieve. Guellen is in ruin. Claire is represented as a superhuman force responsible for this, and Ill is blamed as the cause of Claire’s, and thus Fate’s, selection of Guellen to destroy. Her existence represents the temptation for Guellen to solve their problem through immolation. The people to whom Ill appeals for help all use nauseating and morally obtuse and hypocritical rationales for why his concerns amount to nothing and should be rejected, expressed in indignant tones. Mayor says “If you’re unable to place any trust in our community, I regret it for your sake. I didn’t expect such a nihilistic attitude from you. After all, we live under the rule of law.”[7] Mayor is about to use the community fashioned into a mob to kill Ill; he does so in a morally bankrupt manner, and he is prepared to violate the rule of law. When Ill points out that the coffin prepared for him is being adorned with flowers as they speak, Mayor responds, “You ought to be thankful we’re spreading a cloak of forgetfulness over the whole nasty business.”[8] Since Ill is trying to do precisely the opposite – to expose this nasty business, Ill ought not to be feeling grateful in the slightest. A new typewriter is brought in as they speak. The mayor has his gun and yellow shoes, smokes fancy cigarettes, and has a new silk tie. The construction plans for new developments in the city are definitive evidence of the mayor’s complicity, just as the peal of new bells indicates the corruption of the priest. Ill has nowhere to turn.

The blinded and castrated false witnesses, Koby and Loby, Claire has brought with her, mindlessly repeat each other’s rather feeble statements: “We’re in Guellen. We can smell it, we can smell it, we can smell it in the Guellen air.” And, “We belong to the old lady, we belong to the old lady”[9] as though they contain the seeds of mimetic contagion. These seeds germinate in Act Two when the townspeople start copying each other’s statements in the same manner. One character will speak and “All” will repeat what they say twice. For instance, when the mob menacingly corners Ill when he tries to leave town. The false witness is a key feature of scapegoating. Satan is the accuser who arbitrarily designates the innocent victim to be sacrificed as a scandal. The true Satan throws out the false Satan. It is not the victim who is genuinely satanic, but the one doing the pointing. The Paraclete, by contrast, is the defender; the name for the Holy Spirit in Christianity. Another development in Act Two, is that Claire sits above the action on a balcony and the play alternates between her utterances and commands given to her subordinates from her lofty position and the activities and discussions of the Guelleners, emphasizing her role as marionettist and quasi-divinity.

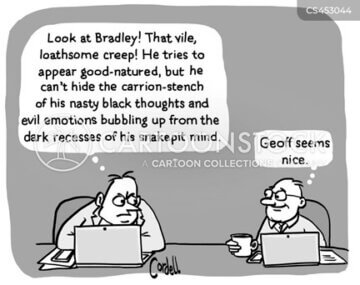

There are few things harder than trying to persuade someone who has a vested interest in not understanding your argument; a point made by Upton Sinclair, H. L. Mencken and others. Imagine trying to help Richard Dawkins find God. His public career would be over. Doctors might have a vested interest in sick people existing, but they can develop no good reputation if they never cure anyone. Fixing or calming race relations, however, does not benefit a race agitator in any way. If people are not riled up, they have failed. Each public university now has a Chief Diversity Officer, or similar title, making on average $209,784.[10] ($252,400 in New York with a high of $364,734)).[11] He needs to both make sure there are “problems” that he is uniquely able to address, and also, that they are never permanently solved, in case his office is disbanded and all that filthy lucre disappears. He has to persecute and scapegoat. If, for instance, he started defending white faculty or students, he would effectively have changed sides. Similarly, all of Ill’s arguments will fall on deaf ears.

Ill has falsely denied paternity and he has bribed witnesses to perjure themselves. This is small potatoes. There is nothing condign[12] about the death penalty for this. In Oedipus Rex, Oedipus both saves Thebes, and endangers it. He solves the riddle of the Sphinx, rescuing Thebes, and unknowingly marries his mother as part of his reward. The Sphinx is otherwise unstoppable and it was she causing the destruction. When Oedipus unwittingly kills his father, it is Apollo who punishes Thebes with a plague and claims that to stop the spread of the disease Thebes needs ritual purification by identifying and punishing the killer. Scapegoating stories need actual gods, or their equivalent, to justify themselves. It does not seem to occur to anyone to blame Apollo or the Sphinx instead, possibly because they are Fate personified, rather than individuals with moral responsibility. Claire has done much worse things than Ill and is now persecuting an entire town on a Biblical scale resembling a plague, famine, flood, or swarm of locusts. Rationally, the town should be angry at her, not Ill. They are not, because Claire is an amalgam of disjoint entities assembled by an economic crisis, not a normal person. She drives the formation of the mob that immolates the victim, only to dissipate once its goal has been achieved. Claire’s existence is fantastical in nature. Yet, the impersonal forces: the mimetic contagion that generates the lynch mob, is all too real; though based on a delusion.

Dürrenmatt’s The Physicists also has an all-powerful woman step in at the end to ensure an unhappy outcome. Inmates at an asylum represent two famous physicists, Newton and Einstein, and the mathematician, Moebius. Moebius has made fundamental new discoveries and “Newton” and “Einstein” have been sent to spy on him and pretend to be mad to get admitted to the asylum. Moebius too has been pretending to be mad in order to avoid having his discoveries used for destructive purposes. Moebius discovers what Newton and Einstein are trying to do and gets them to agree to abandon their goal. Moebius tells them that he has destroyed his notes anyway, for the good of mankind. Dürrenmatt has in mind the Manhattan Project overseen by physicists and other potentially devasting inventions. But, it turns out, that a woman has copied all Moebius’ notes and intends to use them to become the most powerful woman in the world and there is nothing the rest of them can do to stop her. So, after Moebius’ successful attempts at promulgating a peaceful outcome, someone personifying Fate has come along to spoil it all. In fact, no agreement for an eirenic solution for this problem can last because power belongs to he who chooses to break that agreement. Likewise, though countries might agree not to use viruses in biological warfare, they use these viruses to try to generate vaccines just in case some country decides to break the agreement. This seems to have been what the Wuhan Lab was doing, with American funding, having weaponized a virus otherwise harmless to humans, and to have engineered it to be maximally contagious; both called “gain of function.” At the moment, it looks like, with the escape of the virus, distrust concerning biological warfare generated the very problem they were hoping to avoid.

When Claire makes her offer of money for the murder of Ill, Mayor responds in a presumably shocked voice: “Madame Zachanassian: you forget, this is Europe. You forget we are not heathens…I reject [your offer] in the name of humanity. We would rather have poverty than blood on our hands.”[13] A little earlier in the play, the high culture of Germany is also invoked in the form of Goethe and Brahms. “Goethe spent a night here,” “Brahms composed a quartet here.”[14] Though, the reference to Bertold Schwarz as the inventor of gunpowder[15] connects all this advancement with death and destruction too. Just as Germany could indeed engage in brutal, immoral behavior, despite Europe and Goethe, so too will the Guelleners. The connection between Guellen and WWII Germany is also supported by the name of the Mayor’s granddaughter, Adolfina – in a play where all the names are important.[16] The train Claire brings with her contains a coffin to transport Ill’s body once he is killed. This “death train,” in this context, has some distant overtones of the cattle cars used to take Jews to the concentration camps.

Ill becomes increasingly distressed as he sees more and more customers buying on credit, including his own family. Ill notices that the people who have begun to put themselves in debt in a big way all wear yellow shoes. The shoes become the sign that the person has in effect elected to persecute Ill. The yellow shoes figure as a kind of inverted yellow Star of David that the Nazis used to identify Jews. Instead of signaling victim status, yellow shoes here denote a willingness to persecute. In German culture, yellow is the symbol of betrayal, associated with Judas at the Last Supper, and Claire makes her offer of a billion to kill Ill at a banquet held in her honor and the last one where all the town participates. Ill betrayed her all those years ago, and Claire will get the members of the town to break faith with Ill. The yellow shoes also bring out the mimetic aspect of Ill’s persecution as is mentioned by Price in The Political Economy.[17] The persecutors are copying each other’s behavior which, without Ill’s death, will lead to a chaos of unpaid debts and bankruptcies. With Claire’s suggested course of action, the final turn in the mimeticism will be the lynch mob. Towards the end of the play, Ill comments that “Everything’s yellow.”[18] Symbolically, the contagion of mimeticism has reached its apogee.

Hitler, like Claire, offered economic betterment to those willing to vote for and support him. Guellen has been brought to its knees economically by Claire, and this economic incentive proves too much for the townspeople and they become willing scapegoaters. Germany was in the middle of one million percent inflation and economic catastrophe in the 1930s. This seems to have made Hitler much more attractive to the German population. Such a crisis, threatening social cohesion, can be solved by ganging up on a person or minority in shared hatred. This explains why the Holocaust, which took up money and resources, and deprived the Third Reich of some of its potentially useful members, such as doctors and scientists, was not merely inexplicable. It did serve an evil purpose. The Guellener’s pact with the devil mirrors Germany’s embrace of Hitler.

Anthropologically, Ill needs to be found guilty of something before he can be killed. Killing an innocent person has no bonding function. The fact that he is guilty of acting badly towards Claire becomes the convenient excuse to kill him and collect the money. The self-righteousness of the lynchers is an attempt to smother from awareness their own culpability for their immoral actions. The hope that they might recognize this lies in the crucifixion of Christ: the most famously innocent scapegoat. A key moment in the play, from a Girardian perspective, occurs when Ill tries to escape the mob by leaving town on a train – with some vague aspiration to get to Australia, though he has not the money to do so. The plotting Guelleners catch up to him and, while stating that they are all for his trip and will not stop him, surround him and prevent Ill from boarding the train. Their menacing moblike demeanor is exacerbated by their newfound speech habits. Ill comments that he wrote to the Chief Constable of Kaffigen but his letter was clearly not delivered. The people deny that the Postmaster could possibly be involved since he is “an honorable man,” first stated by Schoolmaster and repeated twice by All, and accuse Ill of being incomprehensibly suspicious. Mayor: “No one wants to kill you.” All: “No one. No one.” These are examples of the trance-like dialogical repetition found in Act II first seen with Koby and Loby in Act I. Additionally, the German word used in the original text is actually “niemand,” “nobody.” This evokes Odysseus telling Polyphemus, the giant cyclops in the Odyssey, that his name is “Nobody,” so when Odysseus blinds him in order to escape being cannibalistically eaten, Polyphemus calls out to his fellow cyclops, “Help me. Help me. Nobody has blinded me.” Of course, no one comes to his assistance. Similarly, niemand wants to kill Ill; meaning, everyone wants to kill him. Ill then says: “Look at this poster. ‘Travel South.’” Doctor: “What about it?” Ill: “Visit the Passion play of Oberammergau.” Playing obtuse Schoolmaster asks: “What about it?” Ill comments, “They’re building. Mayor: “What about it?” Ill: “And you’re all wearing new trousers.” “You’re all getting richer and you own more.” The bell rings at that moment, evoking Christian funeral bells. Dürrenmatt has Ill point to the poster of the Passion play with the expectation that the Guelleners will understand the reference; that they ought not to repeat the injustice of the crucifixion. When they fail to get the point, quite on purpose, Ill resorts to providing more evidence that they are clearly planning to unjustly murder him in the manner of Jesus’ lynching. A further pointed reference to Christ and eschatology occurs when Claire first arrives and Ticket Master says “They say the Cathedral portals are well worth a look. Gothic. With the Last Judgment.”[19] Claire responds, appropriately enough, “Get the hell out of here.” The Last Judgment sees the return of Christ.

Arguably, the most beautiful and profound paean to love ever written was Saint Paul’s letter to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians, 13). It puts absolutely everything – faith, hope, charity, philosophical knowledge and insight – everything below the level of love and states that without love, none of these things have value. It is both chastening for philosophers, theologians, and the like, and undoubtedly true. The first paragraph is “If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. 2 If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. 3 If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.” People can either join together as a hateful mob, or they find common cause in love. Dürrenmatt writes that First Corinthians, 13 has just been read at Claire’s latest wedding.[20] When Mayor says that the millionairess is their only hope, Priest comments “Apart from God.” Schoolmaster responds, “But God can’t pay.”[21] Other Christian references appear almost immediately in the play with, for instance, the name of the local hotel, The Golden Apostle.

Girard points out that narratives can be divided into the sacrificial and the revelatory. Thomas F. Bertonneau adds to this that there are scapegoats in films and plays, and the scapegoats of the film or play. In sacrificial stories, the bad guy scapegoats the good guy, and we, the audience, hate him for it. But, this turns the bad guy into our scapegoat. We, the audience, bond in shared hatred and look forward to his punishment. Death or exile. Dürrenmatt is trying to make his play revelatory of the scapegoat mechanism. To do that, he explicitly writes that he wishes the Guelleners not to be presented as entirely unsympathetic. If they are, then the audience can simply write them off as evil people and they become the scapegoat of the play, just as Ill is the scapegoat in the play. Dürrenmatt says in his postscript to the play “The Guelleners who swarm round the hero are people like the rest of us. They must not, emphatically not, be portrayed as wicked.”[22]

This direction is somewhat fraught, because they are in fact being evil – it is just an evil in which we all participate, and their manner of speaking in self-righteous tones, while planning murder, provides an extra-dimension of moral revoltingness. They like to mind-read, engage in Catch-22s, and invoke psychological diagnoses in their interactions with Ill. A description of someone trying to leave an evil cult that once existed in Auckland, New Zealand included the statement made by a nurse, “Your request to leave [the cult] signals that you have a problem with authority. Why don’t you sit down so we can discuss that and get to the heart of the problem?” This smarmy condescending response is a sure sign of a wretched moral delinquency on the part of the nurse and seeming sociopathy. The Catch-22 is that any request to leave the cult makes it extra important that the prisoner stays to “sort it out.” It also means the cult member can only be making his request because of a psychological problem – i.e., you’re crazy if you want to leave. This is also mind-reading; I know the real reason for your request, whatever you might say.

In the group of texts in Matthew and Luke called “Curses against the Scribes and Pharisees” Jesus complains that “I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you kill and crucify, and some you will scourge in your synagogues and persecute from town to town…”[23] Girard says “Jesus is very well aware that the Pharisees have not themselves killed the prophets. . . .”[24] They are the sons of the killers. “This is not to say that there is a hereditary transmission of guilt, but rather an intellectual and spiritual solidarity that is achieved by means of a resounding repudiation. [25] The sons believe they can express their independence of the fathers by condemning them, that is, by claiming to have no part in the murder. But by virtue of this very fact, they unconsciously imitate and repeat the acts of their fathers.” From this point of view, it is important that we accept a common community with the Guelleners. To simply condemn them as wicked is likely to continue to blind us to the tendency to scapegoat endemic to all human culture, and most specifically, to us personally.

Ill goes to see the Priest in The Visit when he realizes that the Guelleners buying on credit means they will need to kill him to pay their debts. The Priest comments: “…you think you know people, but in the end one only knows oneself. Because you once betrayed a young girl for money, many years ago, do you believe the people will betray you now for money? You impute your own nature to others. All too naturally. The cause of our fear and our sin lies in our own hearts.”[26] This speech makes no literal sense because if one “only knows oneself,” the Priest cannot claim to know what Ill is “really” doing. By being the first to accuse Ill of projecting, the Priest appears to hope to avoid also being accused of projecting his guilt for scapegoating Ill onto Ill himself. In projecting, we recognize someone’s guilt or hypocrisy precisely because we suffer from the same defects. Someone self-conscious that they were hired to teach at a university, against the university’s rule against hiring its own graduates, will be particularly sensitive to this eventuality when it comes to hiring someone in his turn. (This situation actually occurred, and the job applicant was vetoed by him.) Or, someone on a college promotion committee might object that the candidate has published in no reputable venues, precisely because this is his situation and he has not forgotten it. (This tenured person had published in a vanity press only). These people were keen to persecute others precisely because these others suffered from the same defect. These defects are wounds which make us particularly sensitive to them. It is only if this is not understood that this behavior seems bizarre. If Ill accuses the Priest of projecting in turn, Ill is more likely to seem to be trying to deflect attention from himself. The Priest’s accusation concerning Ill demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the ways we deceive ourselves, only to be actively attempting to deceive himself and Ill. We see here what appears to be a cynical abuse of insights that should be illuminating, but are instead used to disguise and misdirect. The Mayor projects when he accuses Ill of nihilism, losing faith in the community, and rejecting the rule of law. The Priest betrays his own bad conscience shortly after this speech, when he begs Ill to flee.

The contrast between how the Guelleners should be acting within a genuine Christian context, and their actual behavior, can be seen in the mock prayer at the end of the Golden Apostle Hotel assembly attended by reporters. The prayer, led by the Mayor, sounds vaguely authentic, if wickedly hypocritical, until the Mayor and the citizens pray that their “sacred possessions” be preserved.[27] Their new possessions, far from being sacred, are about to lead to the murder of Ill. Ill’s first response to this, “Mein Gott,” mirrors Jesus’ final words on the Cross, as E.S. Dick comments,[28] though minus “Forgive them for they know not what they do.” The prayer is repeated at the end of the play. [29] In this context, the mock congregation repeating the words of the prayer is yet another sign of rampant mimeticism.

The contrast between how the Guelleners should be acting within a genuine Christian context, and their actual behavior, can be seen in the mock prayer at the end of the Golden Apostle Hotel assembly attended by reporters. The prayer, led by the Mayor, sounds vaguely authentic, if wickedly hypocritical, until the Mayor and the citizens pray that their “sacred possessions” be preserved.[27] Their new possessions, far from being sacred, are about to lead to the murder of Ill. Ill’s first response to this, “Mein Gott,” mirrors Jesus’ final words on the Cross, as E.S. Dick comments,[28] though minus “Forgive them for they know not what they do.” The prayer is repeated at the end of the play. [29] In this context, the mock congregation repeating the words of the prayer is yet another sign of rampant mimeticism.

The scene in the Golden Apostle also has overtones of the visit by the Red Cross to Theresienstadt concentration camp in the nineteen forties.[30] Permitting the Red Cross to film a visit to a prettified concentration camp, the inhabitants of which were later sent off to be killed, represents an amazing display of gall by the Nazis. Similar audacity is displayed when the fictional Guelleners invite journalists to the Golden Apostle to film the final decision to illegally execute Ill. The Red Cross film was used as propaganda for the German wartime newsreels called Die Deutsche Wochenschau – the latter being the same word Dürrenmatt uses in connection with the filming of Ill’s death sentence.[31] The Guelleners, like the Nazis, rely on the visitors (mis)interpreting the events through the hermeneutic lens the former provide. With the Mayor’s prayer mentioned above, Dürrenmatt has the Guellen “congregation” repeating word for word what the Mayor intones. This repetition evokes the Red Cross and the Guellen journalists repeating what they have been told to think. We are lead away from taking the prayer simply at face value because the content of the prayer is so outrageous.

Towards the end of the play, Claire and Ill sit in Konrad’s Village Wood. Along with Peterson’s Barn, Konrad’s Village Wood was one of two main trysting spots for Claire and Ill in their youth. Now the Wood is more of a symbol for the death of love and is especially associated with Claire since she now owns it. Claire’s husband has been sent to inspect some ruins so Claire and Ill can talk privately. When the husband is asked what he makes of the ruins, he says “Early Christian. Sacked by the Huns.”[32] The Gospels are certainly early Christian, and the word “Hunnen” in German doubles as a generic name for barbarians. This gives us a Christian/barbarian contrast that Girard would like. Claire’s husband’s comment applies not only to the ruins nearby, but to the whole of Guellen because Guellen too is referred to as a ruin in the stage directions at the beginning of the play. The fact that the vote to kill Ill takes place at the “Golden Apostle” also indicates a betrayal of what ought to be Christian ideals. The contrast between the way Claire and Ill used to meet and their current maudlin association highlights the way in which the death of love has inexorably led to the victimization of Ill the scapegoat.

Ill’s attempts to wake up the town to their impending moral disintegration give way to his acceptance of his guilt. His lies and betrayal of Claire forty-five years ago are responsible for a great deal of harm to her and now, indirectly, to the economic well-being of the town. Of course, the town of Guellen participated in the victimization of Claire, leading to her leaving Guellen. That is why all scapegoat victims are innocent of what they are accused. They cannot do much harm in isolation. The Guelleners are almost as guilty as Ill for the mistreatment of Claire. Thus, Guellen is included in Claire’s plans for revenge. The town is in debt and this link between guilt and debt seems to be linked to the similarity between the German words for debt schulden, and schuld, which means guilt. The other part of Claire’s revenge is to turn them all into murderers. The town failed to deliver justice in court, and jeered at her status as a supposedly promiscuous woman, forcing her into prostitution. Ill achieves a certain moral status by accepting his guilt and makes peace with his unavoidable murder by coming to view it as retribution for his sins. The Guelleners do no such thing.

It should be noted, however, that it is common for scapegoats to at least begin to agree with their persecutors. Bullies can be quite good at getting their victims to feel bad about themselves – assuming the negative opinion that the bullies have of them. There are plenty of psychological experiments proving the extreme difficulty of challenging absolute unanimity on the part of others. Where we stand alone; where friends and family all concur with the negative judgment against us, it is very hard not to agree with them. “Idios” in Greek indicates the particularity of a person. A person who lives in a world of his own invention rather than the common reality shared by the rest of us. Standing alone is to be an idiot – a madman. Being unfairly fired from a job and feeling bad about it, is partly about coming to share your former employer’s opinion of you. You can seem a loser and ne’er-do-well even in your own eyes.

Those Guelleners most supposed to represent law, order and moral rectitude, policeman, Mayor, and Priest, are revealed to be completely corrupt. Ill appeals to them for help. But all turn out to be participants in mimetic convergence and all are wearing yellow shoes. They also all have loaded guns which Ill correctly perceives as a threat. The guns are to kill the black panther which represents Ill, since “Black Panther” was Claire’s pet name for Ill in their youth. Instead of safeguarding the town, the authorities have joined the lynch mob, buying on credit items they cannot afford without Ill’s murder. Policeman has revealed his willingness to be corrupted before Claire’s offer is even made, suggesting that he would be willing to “get up and dance”[33] for the steak and ham the eunuchs get every night. He also expresses to Claire a willingness to turn a blind eye when necessary.[34] Later, Policeman follows a disingenuous logic, saying “this proposal [to kill Ill] cannot be meant seriously because one billion is an exorbitant price…People offer a hundred, or maybe two hundred, for a job like that.”[35] Ill notes that by the time Policeman says that he has a new expensive gold tooth, is drinking fancy beer, and has yellow shoes. This moral vacuum at the core of society is reminiscent of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, where the hardboiled detective discovers that the evidence of crookedness he has uncovered has no remedy because seemingly everyone everywhere is also corrupt. The fact that Polanski has yet to go to trial after accusations of drugging and raping a fourteen-year-old, indicates that Polanski might not personally be so unhappy about the ineffectuality of the authorities to exact justice

In all this moral morass, Ill comes out of it fairly well. He has indeed behaved despicably in the past, but has now fully accepted his guilt, and even the excessive punishment. Thus, he is not in the kind of hell in which Kafka’s characters find themselves, when they stand accused of something, but do not know of what (The Trial, The Metamorphosis). Accepting his guilt means, for Ill, giving meaning to the town’s intention to kill him. He will die as payment for his former behavior towards Claire. He is not dying to save the town from poverty because it would not make sense to save them from being poor, only to leave them to a worse fate – turning them into murderers.

Morally, only Ill gains any benefit from his impending death. He overcomes his fear of death, accepts his guilt and punishment, and becomes a new man. Ill says:

Mister Mayor! I have been through a Hell. I’ve watched you all getting into debt, and I’ve felt death creeping towards me, nearer and nearer with every sign of prosperity. If you had spared me that anguish, that gruesome terror, it might all have been different, this discussion might have been different, and I might have taken the gun. For all your sakes. Instead, I shut myself in. I conquered fear. Alone…You must judge me, now. I shall accept your judgment, whatever it may be. For me, it will be justice; what it will be for you, I do not know. God grant you find your judgment justified. You may kill me, I will not complain and I will not protest, nor will I defend myself. But I cannot spare you the task of the trial.[36]

The Guelleners start spending money and getting into debt prior to their conviction that there is any justification for killing Ill, and yet killing Ill is their only way out of debt. So, we know that Ill’s murder was not predicated on his guilt for any crime. Nor do Ill’s crimes actually warrant the death penalty. The final reason Ill cannot be legitimately killed is that, as the Priest says, “The death sentence has been abolished in this country, Madam.”[37]

If Ill killed himself, which the Mayor wanted him to do, it would not bring about the social cohesion that is needed. Stoning is the immolation method par excellence, because all participate and no one can later claim innocence, breaking the unity of conviction of the mob. Social media methods of scapegoating reproduce this “all against one” method of lynching. They even use the term “piling on,” just as stoning would create little pyramids underneath which the victim lay crushed.

By choosing to be the willing victim, with caveats, the story of Ill’s immolation follows the age-old pattern of the innocent person murdered (thyein) who is later credited with self-sacrifice, accepting his fate, and dying to save us, renouncing life (askesis). The mob, initially filled with murderous hatred, are later grateful to the victim for bringing them all together and temporarily solving their problems. Sometimes, a statue is erected to the victim. In The Visit, a painting has been painted to hang on the bedroom wall so his wife might better remember him in gratitude.[38] How nice!

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my wife, Professor of German, SUNY Oswego, Dr. Ana Djukić-Cocks, for introducing me to the play, helping me with the German text, offering corrections and other assistance, including several points of substance.

Notes

[1] Friedrich Dürrenmatt, The Visit, trans. Patrick Bowles (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1962).

[2] This link takes you to the search page where the PDF for The Visit can be found. https://www.google.com/search?q=the+visit+durrenmatt+pdf&client=firefox-b-1-d&sxsrf=ALeKk00suiGAUEgm1JvOoXXxCcmCF027ag%3A1626880842493&ei=Sjv4YNyrHZWNwbkPtt2C0AU&oq=the+visit+durrenmatt&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAEYADIHCAAQsAMQQzIHCAAQsAMQQzIFCAAQsAMyCQgAELADEAcQHjIFCAAQsAMyBQgAELADMgUIABCwAzIHCAAQsAMQHjIHCAAQsAMQHjIKCC4QsAMQyAMQQzIICC4QsAMQyAMyCAguELADEMgDSgUIOBIBMUoECEEYAVAAWABggCRoAXAAeACAAVeIAVeSAQExmAEAqgEHZ3dzLXdpesgBDMABAQ&sclient=gws-wiz

[3] The forty-five years Claire has been away connects her visit with 1945, the end of WWII.

[4] Although we are using Patrick Bowles’ translation, we will be using some alternative translations for some words. Bowles translates “Milliarde” as a million. We will be referring to the ‘billion’ that Claire offers, since this is closer to the meaning of ‘Milliarde,’ and because in none of today’s currencies would a ‘million’ achieve Claire’s objectives.

[5] Dürrenmatt, 26.

[6] Ibid, 31.

[7] Ibid,54

[8] Ibid,56

[9] Ibid, 24 and 25

[10] https://www.salary.com/research/salary/alternate/chief-diversity-officer-salary

[11] https://www.salary.com/research/salary/alternate/chief-diversity-officer-salary/new-york-ny

[12] Punishment for a crime of the appropriate severity.

[13] Dürrenmatt 39. Bowles’ translation of “Heiden” is “savages.” We are choosing to translate “Heiden” with “heathens.”

[14] Ibid 12.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ill’s name may seem significant to an English speaker, but in German the word ‘ill’ does not carry any negative meanings or connotations. Ill is not ill auf Deutsch.

[17] Price, David W. “The Political Economy of Sacrifice in Dürrenmatt’s The Visit.” Southern Humanities Review 35.2 (2001): 109-27. p. 119.

[18] The German means literally “gold-plated,” and is a reference to the autumn landscape.

[19] Dürrenmatt 19

[20] Ibid, 64.

[21] Ibid, 14

[22] Ibid 107.

[23] René Girard. The Girard Reader. Ed. James G. Williams. New York: Crossroad, 1996, p. 158.

[24] Ibid, 159.

[25] Ibid, 159-160.

[26] Dürrenmatt 57.

[27] Ibid 95.

[28] This point, made by E. S. Dick in “Dürrenmatt’s Der Besuch der alten Dame: Welttheater und Ritualspiel,” Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie, 87.4 (1968), 498-509 is referenced in Dufresne’s Violent Homecoming.

[29] Dürrenmatt 102.

[30] In June 1944, the Nazis permitted an International Red Cross team to inspect the Theresienstadt ghetto in the former Czechoslovakia. In preparation for the visit, the ghetto underwent a beautification program. In the wake of the inspection, the Nazis produced a film using ghetto residents to show the benevolent treatment Jews supposedly received in Theresienstadt. When the film was completed, almost the entire “cast” was deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp. (Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/index.php?ModuleId=10005424 ).

[31] Dürrenmatt 31.

[32] Ibid, 89.

[33] Ibid, 25.

[34] Ibid, 22.

[35] Ibid, 48.

[36] Ibid, 81.

[37] Ibid, 23.

[38] The painting gets smashed, but Ill suggests painting a new one.