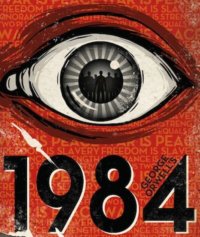

Language, Power, and the Reality of Truth in 1984

In the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four George Orwell presents us with a world where systemic thinking, a form of solipsism represented by the Party and embodied in O’Brien, has come to permeate and dominate all aspects of human living. This type of thinking, which adheres rigidly to its own logic, becomes a form of closed-mindedness that recognizes no perspective other than its own and has become, in the novel, a self-referential totalism that neither acknowledges nor sees the need for any external stimuli. As a consequence all alternative viewpoints are regarded as transgressions, deviations that must be corrected to preserve the integrity of the system in the absolutism of its “purity.” The principal possessors and guardians of this perfection are, of course, the Inner Party with their “special relationship” to the “Truth.” It is they who have created a world where two and two can equal five, where “Freedom equals Slavery” and so on; where anyone, such as Winston Smith or Julia, who challenges the oligarchy, must be, in the terms of its own all-pervading logic, regarded as “insane”: misguided blind fools who need to be “helped” to think in the correct Party-determined way. The Party’s method (before the apparently inevitable requirement for torture) for the imposition and maintenance of its “Truth” is the manipulation of language.

The Party has understood the central role that language plays in determining thought. Orwell, in presenting the Party in this way, seems to curiously anticipate certain trends in current post-modernist thinking. One of the aims of this article will be to examine this element further. I will also consider how Orwell presents the dynamic relationship between language and power and how this constitutes and determines what we sense as reality and thus our experience and perception of truth.

O’Brien and the Party will talk about the history of the past and about history’s relation to power; but it is the control over history in its synchronous mode, history as a dynamic activity here and now and in their control of interpretations of the future, that their domination and determination of the meanings of words gives them – their control of language itself – that is the essential basis of their ability to realize and impose their “Truth” to the exclusion of all others. O’Brien makes the centrality of present-control explicit when, in the Ministry of Love, he orders Winston to repeat the Party slogan, “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past” (Orwell, 1949/83, 232). This is precisely what Winston objects to; and he objects to it on the very ground most likely to offend the Party. Winston rejects this view because it is not true. Winston has already considered this slogan and concluded that “. . . the past, though of its nature alterable, never had been altered. Whatever was true now was true from everlasting to everlasting” (32). Winston, will insist that two plus two equals four, at least for a time – until his very ability to think at all is stamped out; until he cannot but believe the Party’s Truth that it equals five.

Orwell is careful to ensure that we do not lose our perspective. Although he describes at length Winston’s self-questioning as to the accuracy and veracity of his own memories, we are not to suppose that the events they describe never took place at all. Or that he does not remember their essential quality. When, for example, he recalls the final scene with his mother, and we hear him recall her remembered final words to him: “Come back! Give your sister back her chocolate!” (151) we do not doubt the essential reality and relevance of the scene even if we do not assume absolute accuracy in Winston’s recollection of his mother’s exact words. In the statement’s mixture of motherly authority, filial loyalty and the tinge of poignant sweetness leant by the memory of chocolate, Orwell ensures that we realize, with Winston, that the truth is not merely determined by the accuracy of verbal veracity. It is Winston’s sense of the importance of the event for him that is its truth: a combination of actual fact and factual relevance: an ultimately indeterminable ratio/relationship which is the inviolable actual truth for Winston. Arguably this is the most important sense in which the truth exists for us; and it is precisely the sense that in Nineteen Eighty-Four is seen as most subversive by the Party and thus constitutes Winston’s heresy.

This, I suggest, raises a question: why, if the relevance of truth must contain this element of individual experience to be felt as truth, can the Party apparently become so successful at imposing its “Truth” on people in the place of their own truths? The answer, I hope to demonstrate, lies in the effect that the Party’s control of language has on the ability that the population of Oceania has (or does not have) access to its own real experiences at an individual, as well as collective, level. This is where the Party’s power-source is to be found at its most effective and virulent: its ability to determine the nature of the perception of reality, effective reality, inducing a scotosis toward reality per se: the fullness of being. And it is in this control of reality through language that Orwell presents his most convincing and terrifying manifestation of the (mis)use of power.

But how, precisely, can the Party be so effective in this determination of reality? How is it that people can apparently be prepared and willing to accept a version of reality that seems so antithetical to so many of our basic human needs? Well, it would seem that reality is by no means as stable or certain – so concretely “out there” in a Cartesian sense – as our senses may suggest it is. Orwell, writing before post-modernist ideas become current, nevertheless, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, seems to focus on many key elements of a post-modernist understanding about the nature of reality even if, perhaps unsurprisingly, he cannot see beyond them.

Reality, some post-modern thinkers propose, is fundamentally ambiguous: it is not simply “out there.” And this is not in itself a point that I wish to challenge, although I will in turn propose a different version of this ambiguity. For Derrida, reality is a kind of “text” outside of which there is “nothing”; for Badiou it is “the event”; and, for Lacan, although the “Real” happens to us, it is, nevertheless, “impossible.” These are all positions which resonate in important ways in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Paraphrasing Lacan, Zupancic tells us that “the impossibility of the Real does not prevent it having an effect in the realm of the possible” (Zupancic, 2000, 235). Now this is a curious state of affairs; however it does immediately suggest how the nature of reality could be manipulated; and is by the Party in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

For Lacan “the Real” is precisely that which lies beyond language. In his view, language only describes itself, it is always (just) language. Reality – where we live – therefore becomes a kind of effect produced by language. If, for Lacan, the “Real” is beyond or outside of language, it is also presumably beyond human cognition. The result of this “impossibility of the Real” is that language and our use of it in all its historical and socio-cultural contexts becomes our reality. Only this must be a “pseudo-reality”; a product of language, a thing reifiable and thus controllable by language.

The Party controls language and thus it controls the socio-cultural matrix of Oceania, determining Oceania’s reality. Except, of course, because reality is not “Real,” it can be anything the Party wants it to be. This is practically an unchallengeable form of coercion. Newspeak is precisely this: the Dictionary of Newspeak is thus a weapon with its aim to prevent communication and ideas. As Syme assures Winston, ultimately the aim is that “there will be no thought, as we understand it now” (49). The antithesis of this, of course, is “the literature of the past” which Syme claims “will have been destroyed” (49). Humanity and the Party will become synonymous, as O’Brien tells Winston:

“We control life . . . at all its levels. You are imagining that there is something called human nature which will be outraged by what we do and will turn against us. But we create human nature. Men are infinitely malleable . . . Humanity is the Party. The others are outside – irrelevant” (252).

However, if this is the case, then the Party, through O’Brien, is revealing a flaw in its own manipulations. I suggest that those “outside” must be anything but “irrelevant”: it is they who are beyond the Party’s language and, to this extent, they function as an aspect of the “Real.” O’Brien may dismiss them as “proles” and call them “helpless, like animals” but they have functioned for Winston as the representatives of something certainly “outside,” yet certainly not “irrelevant.” Their own lack of consciousness of their relevance has no consequence for the structural and structuring effect the image and idea of them has for Winston. It is his access to the “Real,” like the photograph of Aaronson, Jones and Rutherford, the fact that he knows they exist (or even have existed) is what is important. It is because the other minor characters (Ampleforth, Syme et al) seem not to grasp this importance that their threat to the Party is so puny compared to Winston’s. They are one-dimensional; their human nature is controlled and effectively created by the Party. Regardless of what the Party thinks of them, they never seriously show any desire to challenge it.

The comparatively intelligent Ampleforth assumes his “apparent” guilt and even “works” at providing an explanation for its inevitability, “These things happen . . . I could not help it!” (216). He accepts responsibility for his guilt even as he acknowledges his culpability. In fact because Ampleforth’s and the others’ natures are a product of the Party’s linguistic manipulations, they are literally unable to challenge the Party. The Party’s reality is their reality: they are synonymous with it. To challenge the Party would be to question their very existence itself, even though this existence, from the reader’s perspective, is the obvious result of distortion. When the Party yes-man, Parsons, is thrown into a cell in the Ministry of Love, Winston can ask even him “Are you guilty?” and we are not surprised when the obviously innocent man exclaims, “Of course I’m guilty!”(218) because, of course, by all his Party-induced reference points he is guilty.

Neither Parsons nor the rest of the Outer Party members can relinquish their adherence to the Party. It has become the substance of their world-view. It is certain; to abandon it would be to abandon themselves, which would mean embracing an uncertainty perceived as more threatening than the fate awaiting them at the hands of the Party. It is, as Lonergan has insisted, difficult to resist “the flight into certainty” (see Appendix). We might add any certainty.

By the novel’s end Winston, too, has been forcefully indoctrinated to accept the Party’s reality, but before this happens Orwell affords us a glance at how another path leading to a different, realer, and even ultimate, reality could once have been taken. It is via. his relationship with Julia that Winston sees this. In Julia Winston finds someone with whom he can share not only his feelings about the distortions of the Party, but who, additionally, facilitates his access to his deepest experiential memories – the very events that constitute what is real and meaningful for him. Julia allows him to escape the deadening one-dimensionality of Party-reality. O’Brien, by contrast, remains a solitary figure locked up inside himself. He would even try to make his oneness into a form of pseudo-collectivity when he enthusiastically talks about “Collective solipsism” (249).

Through their relationship Winston and Julia experience the very duality of perspectives that produces a “both/and” quality which can allow access to the uncertainties of the past in a way that enables those very uncertainties to become a reflection of the potential openness and ongoingness of history in both public and private lives. When they are together they become fuller human beings, more complete and more open with both a past and (potentially) a future, thus they move closer to ultimate reality, the “fullness of being.” They are freed from the eternal dead present of the Party.

As Orwell tells us, the positive effects are comprehensive, both physical and mental, Winston had “. . .dropped his habit of drinking gin . . . He had grown fatter, his varicose ulcer had subsided . . . his fits of coughing . . . had stopped” (139). He sees goodness everywhere. Of the objectively ugly prole washer woman he can murmur, “She’s beautiful” while dismissing Julia’s observation that “She’s a meter across the hips” with the all-embracing, “That is her style of beauty” (205). Orwell signals this “realer” reality also in the objects around them, and again an image of sweetness is used to suggest authenticity. They make “real coffee” and Julia passes a curious “kind of heavy, sand-like stuff” to Winston. “It isn’t sugar?” he says. To which Julia replies, “Real sugar” (130). This symbolizes, I suggest, the reality that is constituted by their love for each other. Sweetly genuine, it is a reality based on actual experience and thus in itself authentic. It is in this sense that Alfred North Whitehead considers experience – for him this is the “event” – to be the “realest” reality – at least for living creatures.

Nevertheless I do not mean to propose that Orwell is telling us that this love is in any sense absolute (as the Party insists its “Truth” is) for all its authenticity. It resembles Lonergan’s concept of the “virtually unconditioned” – a conditioned whose conditions are fulfilled, a kind of reality which is relevant and true for the human being(s) experiencing it. In Lonergan’s view the “formally unconditioned,” that which is itself without any conditions whatsoever – the absolutely True – is beyond the scope of human beings. Although in Nineteen Eighty-Four it is this specifically “formally unconditioned” “Truth” of which the Party claims itself to be in possession. The problem for the Party, however, with virtually unconditioned truth would permit individual freedom and would be subject to chance. In short it is not entirely controllable.

This is why the Party cannot allow it to persist; which is why it must “help” Winston and Julia back into a “proper” perception of reality as the Party determines it. To this extent the Party is much like any actually-existing totalitarianism (and Orwell uses Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany as his models). What makes Oceania’s Party different, as O’Brien says, is that it “seeks power entirely for its own sake” (246); and to this extent the novel fulfills Orwell’s intention that it be a warning. However, while I do not propose to challenge the artistic integrity of what Orwell sets out to achieve, I do wish to suggest that Orwell does not have any alternative but to end the novel in the way that he does because he does not have a developed theory at his disposal that would enable him to construct a convincing argument to counter the effectiveness of the logical demands of the totalitarian nightmare he has constructed.

It is necessary then for Orwell’s didactic and artistic purposes that Winston and Julia meet the fate they do. Nevertheless I propose to consider what form an alternative fate for our unfortunate couple might have taken, while also venturing to hope that this will still accord both with Orwell’s didactic and artistic purposes. Orwell originally wanted to call the novel ‘The Last Man in Europe,” with Winston and Julia representing a “risky” hope in the sense of a “Renewal of Nature” such as Prigogine and Stengers talk of when they describe societies as:

“. . . complex systems involving a potentially enormous number of bifurcations exemplified by the variety of cultures that have evolved in the relatively short span of human history. We know that such systems are highly sensitive to fluctuations. This leads to both hope and a threat: hope, since even small fluctuations may grow and change the overall structure. As a result, individual activity is not doomed to insignificance” (Prigogine and Stengers, 1984, 313).

The “risk” is made clear when they go on to say:

“On the other hand, this is also a threat, since in our universe the security of stable, permanent rules seems gone forever. We are living in a dangerous and uncertain world that inspires no blind confidence . . . ” (ibid. 313).

It is not difficult to see how the individual action described here seems to tally with Winston and Julia’s perspective and actions, while the fear of the loss of “permanent rules” suggests the reactionary draconianisms of the Party. I should add that Prigogine’s and Stengers’ concept of the “order through fluctuations” that results from “complex systems” and leads to increasingly more “complex systems” implies an accommodating openness oriented to growth, development, and a radically different system than the Party’s closed-one. This then raises one further question: precisely what sort of scheme or theory would enable us to convincingly propose an escape from Orwell’s inevitably triumphant dystopia?

Well, let us return to the objectification of reality practiced by the Party, what could be called its reification of reality. For the Party, reality is an object, a product, a thing which they can manufacture and thus control. However, this is an erroneous perception of the true nature of things: an erroneousness that is as much a consequence of the deficiencies of our language use and our relationship to it as is the fate, at the hands of the Party, of Winston and Julia as a consequence of its language use. And these, in turn, are both consequences of an increasing general process of reification that has been proceeding since at least the Enlightenment and, as Adorno and Horkheimer have pointed out, an increasing acceleration in our own time – something that Orwell was surely aware of. But, as Eugene Webb, talking about the thought of Eric Voegelin, has pointed out:

“Reality, at its deepest level, is not a ‘thing’ or a ‘fact’, but an existential tension which is structured, through the poles of ‘world’ and ‘Beyond’, as a pull toward the perfect fullness and luminosity of being that is symbolized in the language of myth by the realm of the divine. The substance of reality, in other words, at least as far as it can be known by man in epistemic experience, is nothing other than the love of God. This is, again, to speak mythically; but to articulate in all of its experiential richness a philosophical penetration into the living depths of existence no other language can be fully effective. Existential reality is not known through an objectifying ‘look’ which could subject it to cognitive mastery in the philodoxic mode, but only through the involvement of the whole person surrendering, entrusting, and, committing himself to it.” (Webb, 1981, 126).

The most relevant aspect here is the point about myth; specifically, myth and its relation to language.

For Voegelin, the ability that we have via. language is to create myths, by which he means the attempt to explain in humanly comprehensible terms that which is, ultimately, beyond human understanding (the actual fullness of being). For example, the signifier “God” denotes an entity that, strictly speaking, must be beyond human understanding; however we can grasp the concept of God analogically, usually through some type of myth. Myth, in this sense, is a corresponding to Plato’s concept of Zetesi and Whitehead’s “lure.” To put it another way, our knowledge of God is virtually unconditioned, whereas God is formally unconditioned. We are limited in what we can know.

To this extent our language, rather like our lives, can express, and can only be expressed, in truths. The Truth would be an exclusive aspect of the formally unconditioned. When in Nineteen Eighty-Four the Party seeks to maintain and implement the “Truth,” it becomes the grossest and most pernicious distortion of it. As O’Brien assures Winston, “Never again will you be capable of love, or friendship, or joy of living, or laughter, or curiosity, or courage, or integrity. You will be hollow” (240). Reduced to such a hollowness Winston would be no more than a simulacrum, entirely controllable by the Party (246). The Party really does desire to fill “headpieces with straw.” Alas! And can we not imagine Orwell’s wry empathy as he recalls Eliot’s poem? When the Party has attained full control over everyone, when the world is finally “hollow,” then it will have achieved its goal. It will, of course, be a “hollow” victory. Once the world is hollowed, it is no longer our world.

It is against the drive of this nihilistic intent in the Party that Winston and Julia try to assert themselves and their experiences. Almost until the end Winston can see through O’Brien’s increasingly absurd claims. He cannot suppress his consciousness of their fundamental ridiculousness. His sense of reality persists in its resistance, it will, “. . . like a lump of submerged wreckage breaking the surface water . . . burst into his mind” (260). Winston, while he still has the ability to think for himself as an individual decisively rejects O’Brien’s assertion that, “Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else. Not in the individual mind . . . only in the mind of the Party” (233). Winston, even as he tries to push it under (to avoid imminent destruction), cannot deny his consciousness of an “other” world, the true world: “somewhere or other, outside oneself, there was a “real” world where “real” things happened” (260). This “real” world is the fusion of both outer and inner worlds, the realities of both perception and apperception. It is exemplified by Winston and Julia when they are together. In their selves, with each other, and with the world, a “whole” existence and newfound openness comes into being.

Thus, to be an individual oneself is to ultimately be able to fully acknowledge the individuality of an other while recognizing a shared humanity that would be antithetical to the false collectivity propounded by the Party. Winston and Julia represent the real world, the world that O’Brien and the Party will destroy. The Party can only recognize and therefore tolerate itself, which explains why it can inflict pain so readily and remorselessly. It cannot recognize the actual otherness that constitutes the humanity of the specific individual.

When O’Brien says he is helping Winston to “sanity,” he means it sincerely as it were. “Everyone is washed clean,” he says (239) and even Winston recognizes that “he is not a hypocrite; he believes every word he says” (239). This is the true horror, the real terror that Orwell wants us to feel and be aware of – the inhuman mindless destructiveness of exultant “lunatic enthusiasm” (239). Finally, it is the lunatic enthusiast’s “Truth,” the consequence of their systemic-thinking and its rigid adherence to its own solipsist logic, that Orwell is warning us against. It is a logic that, in O’Brien and the Party, transcends all dichotomies. Ultimately it considers itself beyond even all binaries (even the Party’s own binary – hate Goldstein; love Big Brother – would be finally transcended). Its “God is Power”: it is power and it is God. Only a lunatic believes he is God. God, as we said earlier, must remain a symbol of that which is (and must remain) Beyond: our “lure” that is to be reached for but not attained. Attainment would be a form of hypostasy.

However, it is in Winston and Julia and through their relationship that we see the consciousness of that which is beyond which is expressed and grasped analogically through mythologizing language. For example, the rhymes that Winston is so fond of are a case of a kind of mythologizing language. Their importance lies in their ability to connect Winston to an important aspect of his past experience; thus they function as a kind of portal to anamnesis: they bring the past alive and allow Winston a sense of its meaning and reality. The rhymes allow access to a form of “involuntary memory” of the forceful kind described by Bergson, that brings the past into the present in the same way that we, as individuals too, feel the past come alive.

For example, when we hear a tune or melody that meant something to us in an earlier time. Any sense can be stimulated so as to cause this effect. Proust’s madeleine dipped in tea opening up a panoramic, almost multi-dimensional access to his past experience as a fully consciously felt present experience being, perhaps, the most famous literary example. By contrast, whereas everything is produced, and thus felt, by O’Brien and the Party, is flat and one-dimensional. Nothing really exists in a meaninful way. Even Goldstein and Big Brother probably do not, and never have, existed. Goldstein’s book (the book) is unreal, a fake, as O’Brien tells Winston, “I wrote it. That is to say, I collaborated in writing it. No book is produced individually, as you know” (245). The sort of collaboration afforded by “collective solipsism” must be like a form of talking to oneself for oneself: a room (or a world) of people in this condition could never produce anything new.

Whereas, on the contrary, Winston and Julia’s talking is between two individuals communicating real memories and sharing real experiences and thus leading to new understandings. This is what I have elsewhere referred to as the “ontological necessity” of the human condition: simultaneously an acceptance of human limit and an opening up of human potential. In this sense even just two people can create a new reality, can “generate something” that adds to the world through the fertility of their dynamic inter-relationship, a complex system similar of the kind described by Prigogine and Stengers. The two-in-oneness of Winston and Julia is thus immeasurably greater than the “one-in-oneness” of the Party.

Curiously, perhaps, does Orwell himself seem to recognize a need for something like the concept of God, the Good, the beautiful or a summum bonum. When O’Brien asks of Winston, “Do you believe in God” (252) and to Winston’s negative reply, asks what could defeat the Party, even he knows that Winston’s “spirit of Man” will never be enough on its own. Even if Winston is not the “last man,” the concept of man is finally as “collectively solipsistic” as the solipsism of the Party. Man must reach beyond himself.

But why should the beautiful and the good be more real than its opposite? For philosophers from Plato and Aristotle to Augustine and Aquinas and, more recently, Voegelin, Whitehead and Lonergan, this resolves itself into a question of order. Order here equates with goodness: the harmonious, the intelligible, the God-like, and the summum bonum. For them, to put it simply, history or the meaning of human life are synonymous, a kind of process through which and in which meaning reveals itself as unfolding: a dialogue in which human beings reach (Zetesis) for and are drawn (Helkein) by that which is Beyond. It is a situation in which any and every human individual must acknowledge his or her essential limits, and the limits of the phenomenal universe of sense-perception.

For example, no one is responsible for their own creation; or, further, as Glenn Hughes has put it, “the entire universe of objects and relations in space and time is not a complete or sufficient explanation of its own existence” therefore, as he goes on to say, “existence presupposes prior causes” and “an infinite series of dependent causes does not answer the question, ‘Why does the universe exist?’” (Hughes, 2003, 19). Human individuals should also be aware, even feel drawn by, that which transcends those limits. Thus life can be seen as a form of “midwayness” (what Plato calls ‘metaxy’) – somewhere between the Depth (Apeiron – a kind of disorder or chaos) of the inorganic and the height of the Divine (Nous – at its simplest a highly organized type of order). This form of “midwayness/metaxy” resolves itself as a never-to-be-transcended-as-such tension (taxis), which recognizes itself as both limited to this and yet, at the same time, inextricably linked to its “Beyondness.” Any attempt to deny either the Beyond or the Depth, or to claim a special knowledge of either would be a type of reification that would lead to hypostasis. Just what, in fact, we see O’Brien doing, in the Party’s name for the “sanity” of Winston and Julia.

Oceania is not harmonious, or beautiful, or good, as Orwell makes clear; but it is certainly dedicated to the depths of disorder, and ultimately death, the final descent into the inorganic, and the rejection of life itself. In O’Brien’s words to Winston, we surely see manifested his utter repudiation and rejection of human life and all humanness, as well as any notion of fullness of being, when he asks, “What are you? A bag of filth . . . If you are human that is humanity” (255). Whereas for Winston, in absolute contrast, the prole woman is beautiful fundamentally, despite her physical “ugliness.” Ultimately it is only the good and the beautiful that is real, that has meaning, that is intelligible. It is more like the openness to growth of the “complex-systems” described by Prigogine and Stengers, that leads to the “Renewal of Nature” (Prigogine and Stengers, 1984, 312). The Party must lead to chaos/Depth/Apeiron; while Winston and Julia would lead to greater order/transcendence/Nous.

It would seem that it is a consciously analogical, mythologizing language, a dynamic “metaxic” form that is both real, in the sense of being experienced-based, and yet, at the same time, trans-historical and imaginary and symbolic. To quote Voegelin, it is a form of “consciousness of the Beyond of consciousness which constitutes consciousness by reaching into it [that] is the area of reality which articulates itself through the symbols of the mythic imagination” (Voegelin, 1990, 188) that seems to offer human beings their best chance to be and remain conscious of the summum bonum. Even if this being must be lived out in a contingent and ironic universe where human solidarity-in-openness is the most “certain” thing. This inherent imperfection in human knowledge, in the human condition itself, requires a kind of “faith” because, as Aquinas, utilizing Heb. 11.1, said, “imperfect knowledge belongs to the very notion of faith, for it is included in its definition, faith being defined as the substance of things to be hoped for, the evidence of things that appear not” (ST, Ia – IIae, q.67, 3).

Orwell has presented Winston and Julia as moving through three distinct phases. Initially they are both searching for something. Essentially they each have a need for contact and communication. Winston tries to believe, while writing in his notebook, that he is communicating in a way that can transcend his present. He tells us that the diary is “For the future, for the unborn” (6). Julia, too, wants a specific type of communication with someone who is not submerged in the “dead present” of the Party. She explains her attraction to Winston, “I’m good at spotting people who don’t belong. As soon as I saw you I knew you were against them (113). What they find in each other is the freedom to be for each other and for themselves.

The next phase that Orwell depicts them moving to is what I have described as their “metaxic” middle period, enjoying their mutual discovery that they each possess what Bergson calls “l’ame ouverte,” receptive, outward reaching, hopeful. As such Winston will feel a “mystical reverence” when he senses the immortality of the “valiant figure” of the prole washer woman and, through her, connects with a humanity “the same – everywhere, all over the world, hundreds of thousands of millions of people . . ignorant of one another’s existence” and yet they represent “the power that would one day overturn the world. If there was hope, it lay with the proles!”(205). Winston thus describes a sameness in difference, which is also a difference in sameness: a world made up of people who, like Winston and Julia at this moment, are both individuals and yet meaningfully connected, however unobjectively aware of this they may be.

The final phase of Winston and Julia, as individuals, and in their relationship with each other, comes after they have been “returned to sanity” at the hands of the Party in the Ministry of Love. When they meet for the last time, on a suitably “vile, biting day in March when the earth was like iron and all the grass was dead . . . ” (272) they can see each other, but they cannot now feel what they once had. All they are left with is the sense of their betrayal – of each other and themselves. They have become products of the Party; their souls have been “vaporized” even if their bodies haven’t. Julia’s “thickened, stiffened body . . no longer recognizable” disappears into the crowd, her individuality. The body that Winston knew, and all the shared experience of openness gone as well for both of them, is gone. Theirs has become perhaps the worst kind of existence: an entropy that will not run down. Winston returns to the Chestnut Tree Café and, in a final irony, embraces the only “love” now left for him: “He loved Big Brother” (279).

Orwell has shown us how the use and abuse of language can have potentially tragic consequences. He has also demonstrated how language, power and concepts of truth and reality are complexly interrelated. Nineteen Eighty-Four is particularly timely and relevant to our present world of virulent media where phrases like “alternative facts” and “post truth” are so readily used to destabilize any notions of what may actually correspond to them. If language is thus reduced to a sort of jockeying for position among points of view, then it is also reduced to a power struggle, and the truth becomes merely the dominant viewpoint.

Winston and Julia would have understood why they must accept truths even as they come to know they must reject the Party’s “Truth” for the Truth. Except in Nineteen Eighty-Four they are unable to, and this is what should fill us with horror and foreboding: they cannot; we can. To allow Orwell himself the final word: “Nineteen Eighty- Four could happen . . . The moral to be drawn from this dangerous nightmare situation is a simple one: Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.” This is Orwell’s warning. Luckily for us Nineteen Eighty-Four is still in the future. At least for the time being.

Appendix: Voegelin and the “Ultimate Good”

Voegelin considers the summum bonum to be, in the words, in an unpublished essay, of Elizabeth C. Corey, the “essential condition of rationality itself”, and that this “overarching and governing purpose” must always and everywhere be recognized. In Voegelin’s view, without this “purpose” as at least a structural principle of understanding, there could be no basis for what Oakeshott calls “having a feel” for things.

Unless experience is something, it is, logically enough, nothing. And how could one “feel” nothing? Experience, to speak syllogistically, either has a purpose, or it doesn’t. It is from the resolution of this ur-binary that the dynamic complexities and tensions of human experience evolves. If this ur-binary is resolved negatively, then everything that follows can only be the random groupings of chance or the immanently-curtailed and limited patterns of discrete entities brought together by human design. Their only meaning would certainly not extend any further than what could be deduced by propositional logic.

As Lonergan has pointed out, nothing is not intelligible, and the non-intelligible cannot be said to exist in the rational universe in a necessary or structuring way: it is random chance, statistically inevitable but ultimately meaningless in the sense that it communicates nothing but the fact of its own existence. Hence, subjectivity, if it could be said to exist at all, would be a kind of (meaningless) irrelevance, a random or chance phenomenon itself, and thus an uncontrollable element that could only de-stabilize the universe of discrete phenomena.This is why Oakeshott’s rationalists and Voegelin’s gnostics want to control everything by rules, regulations and ideological, political or religious dogma or ideology – the practical consequences of what Lonergan calls the “flight into certainty” (Lonergan, 1957/1992, 33).

But, if this was the case, how could we describe the “I” that experiences without succumbing to that very “flight into [false] certainty” that Lonergan perceives to be a pernicious loss of our humanness? What, then, is it that apprehends and/or creates the discrete phenomena initially? What, exactly, is having the objective experience? It would seem that there must be some kind of subject that experiences objects for there to be any objects at all! Thus the problem becomes the question of the relationship between both subject and object and object and subject. An apparently irreducible mystery is revealed by the attempt to explain this dynamic tension; and any explanation that fails to treat of both tensional elements qua tension will have to valorize either one or the other element. For Voegelin, a type of reification that leads to an unjustifiable hypostasis. This tendency to hypostasize would, in Voegelin’s view, collapse the tension thereby leading to an imbalance, such in the form of “rational” objectivity. The mystery here is revealed in the recognition that the tension can thus be seen as the “realest” reality. In essence reality could be described as this tension.

It is this in-between state, consisting as it does in the dynamic relationship between subject and object, that Voegelin describes as the metaxy: a form of (historical) process that only as a whole can begin to describe the nature of reality whilst avoiding the aporias of the immanentist hypostases. However if, as Voegelin says, “Man experiences himself as tending toward . . . perfection” (Voegelin,1966/2001,103-104), then the metaxy is not exactly neutral because, if the order of things and order in history is to unfold, it must be oriented toward the divine or Beyond as understood as an unattainable completeness. This is similar to Lonergan’s notion of the “formally unconditioned” as opposed to the “virtually unconditioned” which is available to human beings. The urgent task for human beings thus becomes a dual one: identification of historical structures of meaning that most accurately reflect the ontological necessity (and, logically enough, the identification of those that do not) and the ongoing development of structures that facilitate both human socio-cultural evolution and the continued differentiation of consciousness.

The work of Voegelin, Oakeshott, Lonergan and others would seem to fulfill these criteria. It would seem, perhaps paradoxically, that we come up against one further binary: either we recognize the (structural) necessity of the summum bonum and proceed accordingly or we find ourselves and our history continuing to lurch directionless and lachrymose in this all-too-real vale of tears, with us the ‘players’ on its “great stage of fools.” This must not be regarded as an attempt to deny the fact that events that are irrational or senseless exist per se as things that have happened and will continue to happen. That is to say the consequences of chance, both through human activity and via. natural disasters, accidents and so on apparently seen as “senseless.” This is not rational but it cannot be explained away, however great the temptation. The acceptance of the limit of humanity’s ability to explain is an essential element of the recognition of our condition as “virtually unconditioned.” A failure to acknowledge this limit would lead to gnostic forms of derailment. I would certainly agree this is not an entirely satisfying explanation, but the important point is that it is the only explanation. The randomness is a function in and of our condition (an aspect of what I have called the ontological necessity) even when recognizing this essential irrationality rationally must involve us in an acceptance that it is a condition of aporia; or, hopefully at least, metaxic aporia.

References

Hughes, Glenn (2003) Transcendence and History. The Search for Transcendence from Ancient Societies to Postmodernity. Columbia: University if Missouri Press.

Lonergan, Bernard (1957/1992) Insight: A Study of Human Understanding. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Oakeshott, Michael (1975) On Human Nature. Oxford: OUP.

Orwell, George (1949/1983) Nineteen Eighty-Four. Essex: Longmans.

Prigogine, Ilya and Stengers, Isabelle (1984) Order Out of Chaos (Man’s New Dialogue With Nature). London: Heineman.

Voegelin, Eric (1966/2001) Anamnesis. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Voegelin, Eric (1990) Published Essays 1966-1985, Complete Works Volume 12. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Webb, Eugene (1981) Eric Voegelin, Philosopher of History. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Zupancic, Alenka (2001) Ethics of the Real: Kant and Lacan. London: Verso.

Notes

1. This, I suggest, is a curious example of thought preceding language. What I mean is the frustration one feels at having to use the same signifier–system to signify two essentially different things. The nature of the simple closed-system of the Party (and for all its complexity “Doublethink” is fundamentally banal) is radically different to the nature of the complex open-system described by Prigogine and Stengers and represented by Winston and Julia. This problem would suggest a fundamental difficulty with the perspective on language taken by some post-modernist thinkers, in so far as there must be something beyond or outside of language that we certainly are aware of and can feel even as they await the evolution of signifiers that would enable us to fully describe this ongoing process of differentiation of our consciousness.

2. Not that we should necessarily assume that Orwell himself shares Winston’s optimism regarding revolution from the proles. The only thing we are certain of in Nineteen Eighty-Four is that the docility of the proles can apparently be relied upon. Their unconsciousness and their power presents their lack of self-organization into a threatening order and coherence as an underdeveloped phenomenon that could actually challenge the Party only in potentia. As the street-planners, police and politicians of our own time know, you only need to watch some of the people some of the time, and these are not necessarily going to be the criminal element who, in any case, are never organized enough to represent a threat to the incumbent power-structure of society. Rather it is the law-fearing, law-abiding citizen who, like the outer-Party member, must maintain and uphold – but not threaten - the power-structure, and therefore must be watched, by the inner-Party, whether through the meta-Benthamite telescreen or the remotely-controlled cameras of our own city streets. The Party machinery may change, as may its political persuasion, but this is an evolution-in-kind: it is still there.