Lockheed Martin, Senator Grassley, and the Aerosolized PR-148

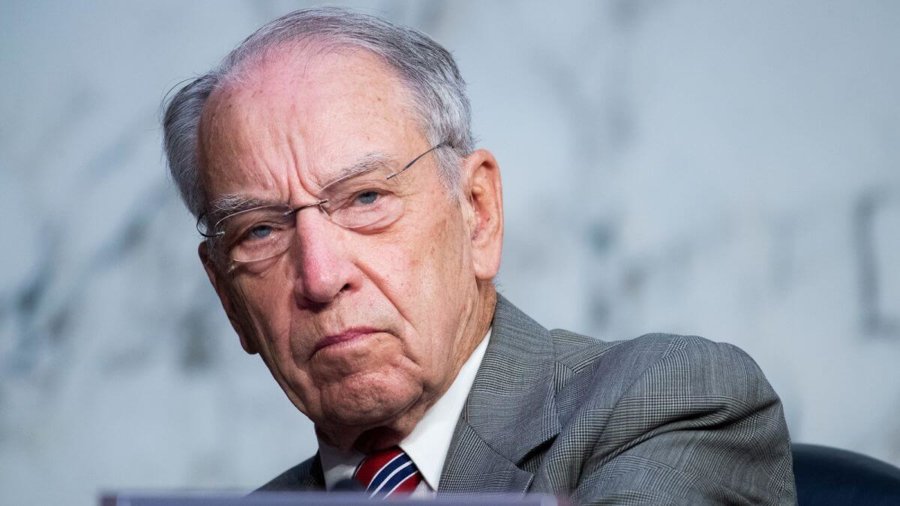

Senator Grassley’s Letter

In late January, 2020, Senator Charles Grassley (Republican, Iowa) sent a letter to the Department of Defense’s (DoD) Office of the Inspector General (OIG). This complaint related to the manufacturing practices of Lockheed Martin, one of the largest defense contractors in the United States. The letter began:

A whistleblower contacted my office with allegations that, until recently, Lockheed Martin (Lockheed) was manufacturing integral fuel tanks for the C-130J cargo plane in a potentially unsafe and hazardous manner. The whistleblower further alleges that DoD’s Contracting Officer Representatives (COR), a government contract specialist charged with ensuring that Lockheed adheres to all contract specifications, failed to address the problem for years. These allegations raise questions about DoD’s ability to conduct oversight of its contractors and a potential culture of coziness between defense contractors and those at DoD charged with overseeing them (Grassley, 2020a).

The letter continues with mention of several other whistleblowers who described just how Lockheed’s manufacturing practices were unsafe, as well as the company’s dismissive reaction to internal complaints, in “ignoring” and “pushing aside” those with concerns about potential health issues caused by unapproved aerosol application of adhesive chemicals. Apparently, DoD took “many years” to begin investigation of the matter, and even dropped their case summarily when Lockheed notified them of intent to rectify their practices.

For Senator Grassley, this raises questions about the DoD’s culture and attention to responsibility which cannot safely be ignored. Grassley believes, and has believed since 1983 or earlier, that the attitude of DoD auditors towards the contractors they are meant to keep in check is too friendly and has “inherent weakness” in that it fosters a view that the contractor is the auditor’s “client” (Committee on the Judiciary, 1983).

There are several groups which are important to this incident as described in Grassley’s letter. These include Lockheed officials, DoD COR and OIG, Grassley himself, and the whistleblowers bringing concerns to him. Other groups could be discussed, and more careful delineation could be made, but for the sake of concision, this document will limit its scope so.

Senator Grassley’s whistleblower accuses Lockheed’s officials of what is, in summary, negligence of regulations and safety recommendations so that adhesives could be provided in aerosol What’s more, only after many years did DoD elements begin to investigate these claims, only to apparently drop the issue altogether when Lockheed sent DoD notice of their intention, via a corrective action report, to stop applying the chemical in aerosol form (Grassley, 2020a).form (PPG Aerospace, 2019; Grassley, 2020a). Presumably, this decision was made because this method of application takes less time, and thus is less expensive, than the professionally recommended brush application of the chemical (PPG Aerospace, 2010).

Grassley also accuses Lockheed officials of pushing aside employees’ concerns and complaints regarding the health and safety implications of this method of application (Grassley, 2020), perhaps failing to satisfy a social or literal contract to honor the voices of employees (McManus, Ward, and Perry, 2018, pp. 166-190).

Despite what one might expect based on the direct impetus for his complaint, Senator Grassley’s primary focus does not seem to be upon this specific issue with Lockheed’s practices in manufacturing the C-130J. Rather, Grassley spends much of his time and many of his sharpest words in criticism of the DoD’s process of auditing military contractors such as Lockheed, even citing a Senate Judiciary hearing and an expert witness as indicating that the DoD’s procedure of giving each COR auditor a long-term assignment to one and only one contractor has an “inherent weakness” (Grassley, 2020a; Committee on the Judiciary, 1983).

Furthermore, in light of the whistleblower’s statement that the DoD “failed to address the problem for years,” Grassley wrote:

“What’s more, only after many years did DoD elements begin to investigate these claims, only to apparently drop the issue altogether when Lockheed sent DoD notice of their intention, via a corrective action report, to stop applying the chemical in aerosol form”(Grassley, 2020a).

Grassley ends his letter by requesting that the office of the DoD Inspector General begin an investigation into the specific case of aerosolized PR-148 in the construction of the C-130J, but also into the matter of “how relationships between contractors and Department oversight personnel may generally affect oversight of government contracts,” and even requests an unclassified report with recommendations for “appropriate remedies and reforms” (Grassley, 2020a).

As a Senator of the United States, Charles Grassley is responsible for representing the people of his state in Congress. One must imagine, therefore, that Grassley has filed this complaint with the DoD OIG because he believes that the people of Iowa are suffering unduly as a result of administrative negligence or even greed within Lockheed, and that the DoD COR has not lived up to their responsibilities to the laborers affected.

The whistleblowers whom Senator Grassley references are most likely private individuals working for Lockheed. These could be people with manual labor jobs assembling the C-130J, or these could be middle-management who feel that the wrong decision has been made, but do not have the internal power to effect change. Regardless, these are private individuals, presumably employed by Lockheed, who feel that the health risks posed by the use of PR-148 in aerosol form are significant.

Aside from Grassley’s letter to the DoD OIG, there are several other pieces of evidence which need to be considered in order to answer the questions raised about this incident, particularly as involve Lockheed and DoD COR.

While one might reasonably question if the COR could possibly be responsible for enforcing health and safety concerns within the workplace of contractors, Grassley provides a very clear statement on this matter. According to his www.senate.gov web-page, “Defense Department officials responsible for this contract are charged with overseeing its compliance with labor and safety standards provided in statute” (Grassley, 2020b).

If not for this statement from Grassley’s office, one might imagine that Lockheed was privately responsible for the safety of its laborers, subject to oversight by OSHA. However, given Grassley’s words, the DoD COR does indeed belong in these considerations.

According to Defense News, Lockheed Martin released a statement in response to Grassley’s accusation. This statement included:

“In regard to the application of a sealant used in the C-130J tank production process, we conducted both internal and external investigations and it was determined that employees were operating within occupational safety standards for production processes including this sealant application process. A team from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration validated these findings” (Insinna, 2020).

With this new information, some of our questions about Lockheed are answered. It seems that Lockheed did make all of the necessary checks to ensure that their employees would not be exposed to unreasonable hazards to their health or safety in the course of their duties to the company. Even aside from direct claims made by Lockheed and Senator Grassley, there are more factual conclusions that can be drawn before we begin analysis, involve safety concerns around PR-148 adhesive promoter and Lockheed’s motives in the use of the product as an aerosol. Based on the information in a PPG Aerospace Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) (PPG Aerospace, 2019), it can be determined just how Lockheed’s claim to fall within safety parameters could be valid despite Grassley’s alarming complaints.

Of the four hazardous components, three are comparable to isopropyl alcohol, with one being that identically. This allows safe human exposure of at least eight hours in concentrations of less than 200 parts per million. The fourth component, a compound of titanium, is considered an irritant (NIH PubChem, n.d.), and makes up a very small portion of the product, between 1% and 5%. One thing not considered by Grassley is the explosive potentiality of PR-148. According to the PPG Aerospace MSDS, the component with the highest vaporous explosive range is isopropyl alcohol; this can easily be managed, so long as the concentration of the aerosol remains below 2%.

With all this in mind, it is easily conceivable that Lockheed management could have done all of the necessary research to determine the details of this material with certainty and ensure that the working environment is sufficiently ventilated to mitigate the risks of poisoning, explosion, and even of irritation. There is one most apparent motivation for the aerosolization of PR-148 adhesive promoter. Just as one might prefer the application of paint via a can of aerosol spray paint over application via brush, one may similarly prefer the aerosol application of an adhesive promoter. This technique allows for quicker saturation, a more even coat, and less variance due to varying skills of workers. Ultimately, this quick and sure application translates into lower labor costs and higher-quality, more regular products. Lockheed, as all others, would love lower labor costs, and in the military market it is particularly important to maintain the quality of a product. This seems to constitute the most likely motivation of Lockheed for the use of PR-148 as an aerosol.

Ethical Analysis

Now that we have established the factual matters of the situation, it is time to begin work towards a determination of the ethical realities. Has there been an ethical or moral lapse? If so, who is responsible, to what degree, and why? These are the questions we must answer in the coming pages using a diverse set of ethical schemas and theories. Before that begins, however, we will briefly examine the immediate message of Grassley’s letter and address some misconceptions.

If Grassley’s letter were to be read and readily trusted by the reader, and no further research done, then the ethical deliberation would be straightforward, brief, and boring. We would conclude that Lockheed management was both negligent and greedy, and that DoD’s auditing structure was totally insufficient to handle the problem of bad actors within a military contract. We would decide, ultimately, that both Lockheed and DoD had failed to satisfy their duties to each other, to their employees, and to the American people. However, thorough research shows that some of the claims and assumptions made in Grassley’s letter are not totally reasonable. The assertion by Grassley and his whistleblowers that these working conditions are potentially hazardous is contradicted by Lockheed’s statement, OSHA’s verification, and a brief independent consideration of the viability of using PR-148 safely as an aerosol (Insinna, 2020). This puts the entirety of Grassley’s case on shaky ground, and we are left with doubts about whatever of it remains.

Given that all parties involved operate primarily or solely in the United States, it is tempting to begin the analysis of this subject with an ethical theory in harmony with the American ideals of capitalistic trade. For that reason, the theory of Ethical Egoism has been chosen. Ethical Egoism is an ethical theory based in the assumption that an action is ethical provided that it is reasonably believed to be in the best interests of the actor performing it (McManus, Ward, and Perry, 2018, pp. 84-103). Initially, this sounds harmful and shortsighted, as it would seem to suggest a selfish and shallow manner of interacting with the world and with other people. McManus, Ward, and Perry illustrate, however, that this selfish way of thinking need not be shallow at all (85): it can rather stem from a good understanding of game theory and the attempt to allocate one’s resources as well as possible to improve one’s long-term outcome.

While this does not result in altruism, it does result in helping others for the sake of virtue signaling, future favors, earning gratitude, etc. It results in obedience to laws, as the punishments are, ideally, proportional to the crime in such a way as to discourage commission in the first place. Furthermore, the American economic philosophy of capitalism is based upon the theory that an amalgam of self-interests throughout a population will balance against one another, and the property of societal good will emerge. This has, more or less, proved correct, insofar as currency can measure societal and individual good.

One schema that is useful in the moderation of ethical egoism is that justified decisions will generally be accepted, regardless of future knowledge, idealism, or actual outcomes. Therefore, it is wise to ensure that all of one’s self-interested decisions as an individual or as a corporation like Lockheed are retroactively justifiable. In essence, this is an effort to guarantee as well as possible that all of one’s decisions support one’s self-interests in the long term rather than merely in the short term.

It seems that Lockheed Martin has done all of the necessary work to justify its decision to use PR-148 in aerosol form, and that this has been vetted by OSHA. It seems that it is in Lockheed’s interest to use PR-148 as an aerosol because it will result in more regular products and lower labor costs. Furthermore, it can be assumed that this is in the interest of the American military and the American people, as these more regular and less expensive C-130J Hercules planes will serve the U.S. in critical missions. Therefore, as a retroactively justifiable decision which reasonably serves the interests of Lockheed, it is reasonable for PR-148 to be aerosolized.

As a side note stemming from discussion of balanced self-interests in a capitalistic society, it seems that Grassley’s statement that the structure of one contractor per COR is ”inherently weak” (Grassley, 2020) could be interpreted in this fashion. This close and long-term relationship between a COR and management of a contractor could, hypothetically, result in a perversion of interests, indicating a failure of the auditor to distantiate himself successfully from the situation at hand, allowing sympathies to come into play (Bennett, 1974; Harter, 2017).

The COR is financially incentivized (and contractually obligated) to represent the interests of the U.S. government to the company to which he has been assigned. If this remains in his best interest, he will carry out his duty. It is, however, in the interests of the contractor to make the COR to some extent sympathetic with them. If this perversion of the COR’s interests can be accomplished, if his judgment can be so undermined, then the COR will now have conflicting interests and incentives, making it less likely that he will effectively represent the U.S. government. This is the “culture of coziness” (Grassley, 2020).

Additionally, one imagines that assigning a COR to multiple contractors over the course of his career would provide him with more information and context, allowing him to make better decisions. Just as the free market must be based on free information for healthy competition, so must the regulated market of contracting have some mobility of information to incentivize competition through products and through internal policies and ethics. If a COR moves from contractor A to contractor B and finds that B makes significantly more internal mistakes than A, the COR may be able to lodge complaints justifiably that otherwise he may not even recognize.

Another ethical theory which bears close resemblance to the customs of the United States is Social Contract Theory. This theory states that behavior is ethical if and only if it is within the bounds of a contract, implicit or explicit, agreed upon by the general population of a society. In the U.S, this means that actions are ethical if they are within the bounds of the law, of social norms, and of actual contracts struck between parties. Additionally, this means that subcultures and organizations have some autonomy of their own to determine an internal balance and set of laws, provided this is not in violation of the overarching social contract.

In most corporate environments, there are explicit and unspoken contracts between management and workers. Management relies upon a certain quality of labor, fine behavior, and adherence to policy. In turn, workers can expect fair treatment, decent salary, and internal representation. This exchange is just an example, but these are fairly common basic guidelines of the contracts in a corporate space.

There are two basic ways to consider the PR-148 situation in terms of the social contract. The most obvious is to consider what the employer owes to the employees in a reasonable corporate relationship, see that the workers are not satisfied with their working conditions, and conclude that there is a discrepancy. It seems, from the story Grassley tells, that the workers began by taking the issue to their supervisors, who responded by “pushing [them] aside.” This sounds damning, but that is only Grassley’s phrase indicating that Lockheed management did not believe there to be a real safety concern.

Of course, when the two parties of the contract disagree, it is acceptable for the party which believes itself aggrieved to appeal to a higher contract for guidance and oversight. In this case, that means that the workers appealed to the DoD and then to Grassley, who represents both his constituents and the overarching social contract. However, while it is Grassley’s job to handle this case at a Federal level, I have taken it upon myself to consider these matters in light of a factual context which I have researched, and I disagree with Grassley’s argument that Lockheed and DoD are at fault for a grave misdeed.

The Complaints

I have no real reason to believe that Lockheed has put its workers in danger or failed to satisfy any constraint of U.S. law in this incident. Rather, I see that they have done all due diligence to the issue, confirmed the safety of their working environment with OSHA, and, I can only assume, made the state of affairs plain to the laborers responsible for manufacturing these fuel tanks. Despite this, it seems that some workers are discontent to the degree that they should literally make a federal case of the matter. While this is of course not a criminal deed, and whistleblowers are (and must be) protected closely by law, I do not believe that the complaints here are justified.

Although Lockheed leadership has seemingly committed no crime or gross ethical violation, it still should not be said that they are to be held entirely blameless for the consequences of the situation which arose in their plant. That is to say that beyond ethics and law, the field of leadership studies tells us that in many cases, the responsibility of defining, declaring, and communicating policies falls to the leader. This is especially true in places of business, where such policies affect not only the health and safety of laborers, but also the bottom line of the firm instituting policy. A manager or overseer is responsible for the productivity, as well as the safety, of the workers overseen, and can commit an error harming the company without risking the safety of the workers.

In this case, it appears that the policies governing the application of PR-148 in the plant were misunderstood by some portion of the workers at this Lockheed plant. Initially, that may be the fault of a worker having failed to read an MSDS or standard operating procedure (SOP), but once this concern was raised with management, leaders at the plant ought to have taken it upon themselves to settle the issue quickly and decisively. By what mechanism precisely leadership personnel handled the dispute we may never know, but the outcome clearly left workers feeling that their complaints had been dismissed without due consideration. A negative appearance developed around the issue, and some of the laborers got to thinking that they deserved better. Eventually, this led to one employee going public with the complaint, and to politicians and media outlets flocking to the issue in an attempt to bring justice, to earn votes, and to claim advertising money.

With all of this information and consideration taken in hand, it seems that the error committed here is one of communication between leaders and followers in a high-importance workplace. Without knowing the details of the discussions had between Lockheed managers and workers, the author argues that this break likely took the form of insular leadership in the style of Barbara Kellerman’s description (Kellerman, 2004): leadership appears to have mentally separated their interests from the interests of the employees, and in so doing crippled the important lines of communication over which information was exchanged in the daily operation of the plant. Lockheed ought to understand what a “public relations disaster” means and how to avoid one — and in all likelihood, they do. This may well have been a one-time issue caused not systemically, but by a disinterested and distant leader in plant management or human resources at the facility in question.

One can picture the jobs being lost over this, and not just on the part of the whistleblower. A firm as big as Lockheed is not too big to fail, but rather too big to take risks. If they were able to determine the root if this incident, they will have rectified it. Ultimately, the case against Lockheed and DoD is boiled away by significant evidence suggesting that there is no danger, no guarantee that facts were hidden from workers, and no concrete reason to believe that Lockheed or DoD has mismanaged anything. One supposes a case could be made against the whistleblowers themselves, based upon their unjustified complaints, but this would have to remain a moral and social case, as a whistleblower should rightfully not suffer for an error in judgment such as this. Additionally, there is some significant responsibility of leadership personnel not just to avoid obfuscation, but actually to communicate explicitly the priorities and purposes of company policies to employees. This shifts some portion of the blame back on to Lockheed leadership again. On the whole, however, this situation seems to be characterized by a series of moral overreactions.

References

Bennett, J. (1974). The Conscience of Huckleberry Finn. Philosophy, 49 (188), 123–134.

Grassley, C. E. (2020a, January 22). [open letter]. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://www.grassley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01-22%20CEG%20to%20DOD %20OIG%20%28C-130J%29.pdf.

Grassley, C. E. (2020b, January 23). Grassley Seeks Investigation of Lockheed Manufacturing Contract, Worker Health Complaints. Retrieved March 4, 2020, from https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-seeks-investigation-lockheed- manufacturing-contract-worker-health.

Harter, N. (2017). No One, Everyone, Anyone. Leadership and the Humanities, 5 (1), 41–50.

Insinna, V. (2020, January 23). Senator calls for investigation after whistleblowers raise concerns about c-130 production practices. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2020/01/24/senator-calls-for-investigation-after- whistleblowers-raise-concerns-about-c-130-production-practices/.

Kellerman, B. (2004). Bad leadership. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

McManus, R. M., Ward, S. J., & Perry, A. K. (2018). Ethical leadership. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.

NIH PubChem. (n.d.). Titanium tetrakis(2-ethylhexanolate) (compound). Retrieved March4, 2020, from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Titanium-tetrakis_2-ethylhexanolate

PPG Aerospace. (2010, June). PR-148 Adhesion Promoter Technical Data. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from http://www.ppgaerospace.com/getmedia/c177f8b9-ef14-48bc-87d7-b0ce3949ad6f/pr_148.pdf?ext=.pdf

PPG Aerospace. (2019, June 18). Safety data Sheet: PR 148 AF. Retrieved February 19,2020, from https://buyat.ppg.com/EHSDocumentManagerPublic/pdf_main.aspx? StreamId=5d09683cf698cbe80000&id=5d09683ef6afd4930001