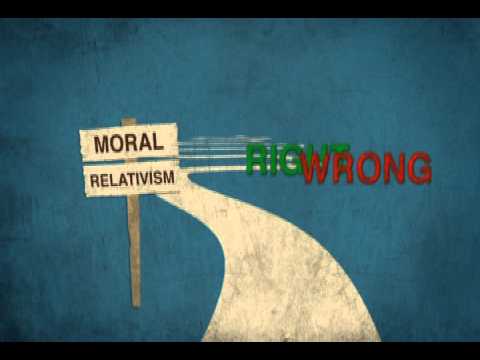

Moral Relativism and Moral Realism

Moral relativists, also known as moral “subjectivists,” believe that all moral perspectives are equal. Thus, we should be tolerant of other people’s moral views even when they disagree with us. Since all moral perspectives are equal it is wrong to rank moral perspectives as better and worse. All value judgments involve ranking attitudes, actions, feelings, perspectives, etc., as better and worse, more and less valuable.

The first problem with moral relativism is that it is self-contradictory and is therefore false. In the very act of asserting the truth of moral relativism you are denying the truth of this assertion.

- First, if all moral perspectives are equal, then moral relativism, being a moral perspective, is no better than the alternatives. If you believe moral relativism is true and therefore the best moral position, then you are committed to saying that it is no better than any other theories because all moral perspectives are equal. You cannot advocate moral relativism without contradicting the assertion of moral relativism that all moral perspectives are equal.

- Secondly, moral relativism claims that all moral perspectives are equal, therefore, it is wrong to rank one moral theory as superior to another. In other words, not to rank is better and superior to ranking. But this means you are ranking not ranking as better than ranking, which is ranking. The more you hate ranking, the more you are committed to saying that ranking is morally wrong and involves making a moral mistake, the more you rank; ranking not ranking as better than ranking. Thus, ranking is unavoidable and you are back to having to decide which moral perspectives are better than others.

- Thirdly, if you a moral relativist because you are in favor of tolerance, then you rank tolerance as superior to intolerance, thereby contradicting your position.

There is no such thing as true contradictions. The law of non-contradiction is a pre-condition for rational discussion. If your parents say – if you are good, you will get a bike for Christmas. You have been good. But you are not getting a bike for Christmas, they are contradicting themselves. The premises cannot be true and the conclusion false. Assuming the truth of the premises, one cannot deny the truth of the conclusion. If you do, you are contradicting yourself and further discussion is pointless because what you are saying is unintelligible, unintelligent and irrational.

Reductio ad absurdum arguments are arguments showing that the logical implications of an argument contradict propositions you know to be true. If an argument implies or entails that the sky is not blue on Earth on a cloudless day then the argument must contain at least one false premise. You know the sky is blue. Any argument contradicting this fact must be unsound. A sound argument is one that is both valid and the premises are true.

A reductio ad absurdum argument shows that adopting a particular belief leads to absurd consequences; namely that a particular assertion directly contradicts something else that you think you know to be true.

If I try to persuade you that taking heroin is a really good thing to do; that although you may enjoy coffee in the morning or a Red Bull, taking heroin is so much better. In fact, taking heroin is so much fun that typically the heroin addict loses all desire for romantic relationships, for sex, for friendship, for family relationships, for leaving the house, for work, for fulfilling interests and goals. In fact, heroin addicts are often willing to rip off family members and friends, to steal and mug other people, just to feed their habit. They will even risk death from overdose because the purity of heroin is unregulated and the amount that is pleasurable one time can kill you the next. That’s how good heroin is. You are typically willing to sacrifice everything else of value in your life. Their addiction becomes the most overriding interest in their existence. Then you should respond that taking heroin would contradict your ideas about what constitutes a good life. You have no intention of abandoning all the things just mentioned because you consider them all part of a good, meaningful life and giving up all those things would be to contradict your goal of having a happy, fulfilling life.

The belief that taking heroin is good contradicts a large set of other beliefs about the kind of life you want. Your beliefs about living a good life are inconsistent with the claim that it would be good idea to take heroin. In order to avoid contradicting yourself you will need to either abandon all your ideas about what you want from life, or the idea that it would be good to take heroin. They cannot both be true.

So, reductio ad absurdum arguments are trying to persuade someone that an assertion he has made is inconsistent with something else he believes. One way the argument can become unpersuasive is if the person you are trying to persuade just accepts the logical implications of his initial assertion and replies, following the above example, “I guess I do not want to live a long life where I am not addicted to heroin and I have changed my mind and now agree that I do not care about the consequences for my family, friends, and work life.”

A more prosaic example would be a kid saying “I don’t want to take my jacket.” The parent says “Do you want to get cold or wet?” The child says, “No.” Parent: “Then take your jacket.” The child’s idea that he does not want to take his jacket is inconsistent with his desire not to get cold or wet. Logically, the child could renounce his desire not to get cold and wet, in which case he need not take his coat. But, usually he will not, and the parent’s argument will be persuasive.

Coming back to morality, if moral relativism is true then Hitler’s moral perspective must be morally equivalent to Jesus’s moral perspective. But this is absurd. You don’t believe this. You know that Jesus’ moral perspective is superior to Hitler’s. Moral relativism has a logical implication that you know to be false. If in fact Jesus’ moral perspective is no better than Hitler’s, then this makes nonsense of any notion of “good” or “bad.” Moral relativism would be indistinguishable from moral nihilism.

In fact, this is the case. Moral relativism leads directly to moral nihilism. Moral nihilism is the belief that moral goodness and moral badness do not actually exist. They are mere fictions. If all moral perspectives are equal, this can only be because there is no truth to the matter. Good and bad are whatever you say they are and are therefore arbitrary. If you can’t be wrong it is because you can’t be right either.

In practice, nobody is a moral nihilist. All moral nihilists are hypocrites. They do not believe their own avowed position. If you were to pound on their car with a sledgehammer, or to cover them in lighter fluid and threaten to set them on fire, they would be powerless to stop you. They could not say “what have I done to you to deserve this?” since they do not believe in justice. Nor could they appeal to kindness, the goodness of mercy, the right to own property, appeal to your “better” nature or use phrases like “don’t be mean.” They could not call the police without contradicting their supposed convictions since the criminal law presupposes moral truths.

Even Adolf Hitler was not a moral nihilist. He just had incorrect moral beliefs, such as the belief that Jews, homosexuals, gypsies, communists, Slavs, and anyone who opposed him, ought to be put to death.

Being Tolerant

Moral relativism probably was taught in order to promote tolerance. Just as there are definitely tall people and rich people, it is hard to say exactly when someone starts being tall or rich. There are borderline cases that are hard to decide. The same is true in morality. Helping a little old lady across the street, when she wants to be helped, is good. Intentionally running her over in your car is bad. Most of the criminal code correctly identifies evil things like murder, rape, assault, theft, fraud, breaking and entering, arson, car jacking, etc..

However, you should never tolerate actually evil things. That was not the original intention or moral relativism. Some students think that in order to be really morally good, they should learn to tolerate slavery and the Holocaust.

Do not confuse tolerate disagreement when there are borderline cases that are genuinely hard to decide, and “tolerating” outright evil things like murder, rape, etc..

Moral Realism

The alternative to moral subjectivism or relativism, is moral realism. Moral realism is the notion that good and evil actually exist. They are not matters of opinion. If two people disagree about a moral issue, they cannot both be right. If one person is in favor of barbecuing living human beings with a flame thrower and another person disagrees, one of those two people is wrong.

Barbecuing people with flame throwers is immoral because it violates “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” This is a suggestion that is based on justice, fairness and reciprocity. If I do not want to be engulfed in flames and be burnt alive, then I should not do that to someone else. That is only fair.

If I do something nice for you, you should do something nice for me. At the very least, you should not return something nice for a positive harm. If I spend the day helping you move and you punch me in the face, then that is not fair. If I share my food with you, then you should share your food with me. Even chimpanzees do that.

No human being, other than psychopaths, doubts that fairness is just and that it is true. Someone who thinks that if someone buys you a cup of coffee you should be mean to them is just wrong and we all know that.

How do we know that fairness is true? It is hard to say. It is even a bit of a mystery, but we do know it. This can be compared to the fact that one day old babies prefer beautiful faces to plain ones. How does the baby even know what beauty is? We do not know. But it does know it.

Moral realism can then be combined with “epistemic fallibilism.” This is the notion that we do not always know which is which – what is right and what is wrong. We are fallible. Usually we do, but sometimes we get confused and then we have to ask our friends and relatives what they think we should do. Under such conditions, reasonable people can disagree and then we agree to disagree if necessary.