Music and the Enlightenment

Some of the most profound changes ever to befall Western art music happened in the middle of the 18th century, around the time of the death of Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frederick Handel, the two greatest composers of what we now call the High Baroque period. With hindsight we can see these changes as effecting the transition from the Baroque musical world of Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi to the Classical one of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven—and thereby facilitating the subsequent turn to Romanticism and thus affecting music for generations to come. But the changes in musical style in the mid-18th century were accompanied and influenced by a great many changes in society and thought too.

Donald Jay Grout in his History of Western Music draws attention to the stark contrast in statements about the meaning and purpose of music as expressed by a writer of the late 17th century, Andreas Werckmeister, and one of the late 18th, Dr. Charles Burney. For Werckmeister, music was “a gift of God, to be used only in His honor”; writing in 1776, Burney (one of the first music historians and an acquaintance of Dr. Samuel Johnson) opined that “music is an innocent luxury, unnecessary, indeed, to our existence, but a great improvement and gratification of the sense of hearing.”

Although we should bear in mind that these are the statements of two individuals, reflecting their respective temperaments and outlooks, it would be foolish to deny that they represent a change in the general drift of thought during the century that separated the two writers. What happened, corresponding to the shift from what music historians discern as the Baroque to the Classical era, was the intellectual and cultural movement known (for better or worse) as the Enlightenment. The fact is that the body of Western art music that is most highly praised and most widely performed and listened to today coincides pretty neatly with this historical period called the Enlightenment. What does this mean?

The Enlightenment meant many things for music. Speaking broadly, these things could be expressed by such terms as popularization, simplification, democratization, and secularization. Enlightenment thinkers believed that music should be accessible to all, reflect what was “reasonable,” and express the ordinary sentiments shared by all of humanity. The democratization of music had far-reaching effects; it is the reason why we are able to enjoy great music in such widely diffused forms today. Broadly speaking, the late 18th century saw the shift from an “aristocratic” expression and understanding of music to a “democratic” vision that would set the stage for the “individually expressive” model of Romanticism.

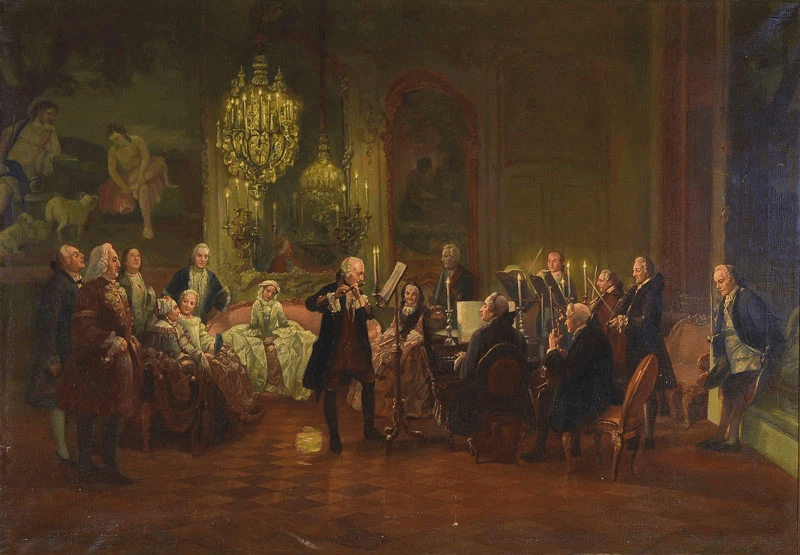

In the era in which the Baroque composers Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi were born, art music was cultivated and patronized within the church and the houses of the aristocracy. When musicians got together to make music, it was either a service of divine worship, or an informal session of secular music purely for the pleasure of the participants, or a private event in the courts of the nobility. Most of the patronage for musicians and composers was provided either by members of the church hierarchy or by wealthy aristocrats, who often employed a staff or entourage of musicians to give private performances and provide music for all sorts of social functions.

With the growth of the middle class, public concerts were born, drawing larger and larger audiences for music, which now became a performance given before a paying public. As democratic ideals swept the Western world in the mid-to-late 18th century, music was one of the arts most affected. No longer was serious art music to be the special preserve of aristocrats and connoisseurs but could and should be enjoyed by all. Thus, Mozart’s piano concertos and Beethoven’s symphonies were premiered in public concerts at various theaters in Vienna, led by the composers themselves. This popularization of music involved a substantial change in musical style, which explains why the music of Beethoven sounds so different from the music of Bach; we will get to this later.

For now, let us note that the secular spirit of the Enlightenment also began to affect music. Of course, sacred and secular music had always coexisted in the Western tradition. But whereas the church had been perhaps the dominant source of the performance of music and the patronage of musical talent since the Renaissance, this dominance began to weaken as the 18th century progressed. To be sure, a composer’s patron was often the local archbishop, and liturgies still demanded new music—witness the many Masses and other liturgical music written by Haydn and Mozart—but in time this type of music came to take up a much smaller proportion of composers’ work. Compare the amount of sacred music written by Mozart, and its proportion within his total output, with the amount of sacred music written by Beethoven, which amounts to a handful of works.

One should not mistake quantity for quality here. While it’s true that Beethoven wrote only a few sacred works, one of these is the massive Missa solemnis, one of the finest works of religious music ever composed. Perhaps the pattern can be interpreted in this way: religious works became fewer in number, but arguably grander and more important in character. Whereas the typical 18th-century court composer churned out Masses as a matter of course, the 19th-century composer wrote religious works as a deliberate choice and as a significant event in his output.

All these changes were, in part, a result of the breakup of the patronage system. In the past a composer relied on a powerful patron, who gave him specific projects for specific occasions. From now on composers would become freelancers who wrote music on their own impulse or for commissions and occasions as they arose. The business of creating music would become less ruthlessly practical, more poetic and individualistic—in a word, more Romantic. Mozart and Beethoven both embody the shift to the freelance lifestyle that would characterize the Romantic artist.

With the emergence of the public concert, the musical genres which composers wrote in and audiences wanted to hear also shifted. Audiences paying to hear music wanted it to be different from the music they made at home, and so chamber music and orchestral music became sharply differentiated. One of the results was the emergence of the symphony, which would be the emblematic musical genre for generations to come. In the field of chamber music, such genres as the string quartet and other formations with the newly popular piano came to the fore.

Where actual musical style is concerned, Enlightenment ideals had a profound effect. The High Baroque style in general is characterized by rich counterpoint, dynamic movement, and a monumental grandeur in the musical architecture. It is music to give glory to God or to impress and please listeners truly wise in the ways of music. This changed with the growth of democratic ideals that stressed the needs of the “common man.” Since the new middle class had little knowledge of musical complexities, they demanded music that was simpler and easier to comprehend than, say, the learned fugues of Bach. A new emphasis on the ability of music to express sentiment and “natural” feelings led to a drastic simplification of the musical texture. Instead of complex polyphony, composers after 1750 began to emphasize a single melody line, tuneful and “singable,” supported by a simple bass line, with harmonic filler in the middle. Music was almost always in major keys now, suiting the prevailing mood of cheerful optimism; the emotional complexity and subtlety of the minor mode was avoided. The resulting style, ready to please and entertain, was known as style galant (gallant style) or rococo (from a French term denoting elegant ornamentation in home décor).

This was of course the era of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the social philosopher who was also a theorist of music and an amateur composer. Rousseau’s definition of music—“the art of pleasing by the succession and combination of agreeable sounds”—pretty well sums up the sound and style of music in the three or so decades after the death of Bach, music that aimed to charm and please but little more. For an example of the shift, compare one of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos with a symphony by Stamitz.

Bach himself was aware of the changes in musical fashion in the later part of his life and resisted them, resolutely composing in the lofty High Baroque manner until the day he died. His sons followed the new trends; but they also ended up saving music from the narrow side of Enlightenment musical taste that was, arguably, just bourgeois mediocrity and a straitjacket on music’s full expressive potential. In doing so, they opened up the horizon for Western music’s future.

Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach, Johann Sebastian’s second surviving son, added emotional depth to the lightweight rococo manner by developing the Empfindsamer Stil, or sensitive style, based on wistful “sighs” and mercurial changes of mood. Contrary to rococo fashion, he did not limit himself to major keys but exploited the stormy moods and deeper emotional resonance of the minor. From Johann Christian Bach, the young Wolfgang Mozart learned the art of composition; J.C. also passed along to him the glory of the music of the greatest Bach, his father, Johann Sebastian, which had become deeply unfashionable. When Mozart wrote his most mature works, such as the unfinished Requiem, the contrapuntal gravitas of Bach became one of his key ingredients. The Baroque style enriched the late music of Haydn and the music of Beethoven as well, such as the Missa solemnis.

The mature music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven—the Viennese Classical composers—reflects the best ideals of the Enlightenment in that it embodies rational clarity and order and makes a direct appeal to the listener without undue obscurity. At the same time, their music does not reflect the narrow vision that would confine music’s purpose to the immediately pleasing and entertaining, ignoring the art’s capacity for the transcendent. At their greatest, all three composers would reach far higher than what the canons of “reasonableness” and immediate pleasure demanded. What they produced—along with the best of the High Baroque—forms the backbone of a repertoire of music that is recognized and celebrated as some of the greatest ever written.

By the end of the 18th century, things had come full circle. Western music’s regression into childhood after the death of Bach was, thankfully, a stage that was soon outgrown, a fallow period that would give way to a new musical harvest. Through it all, the best musical traditions were sustained by the sons of J.S. Bach, carrying on the spirit of their father while synthesizing his achievements with the best of newer trends—keeping what was good, discarding what was trivial. As with many changes in society or art, some old things were lost, yet the best of the past was reincorporated into something new and grand and enduring.