My First Teaching Non-Anxiety Dream

I don’t know how many academics and former academics have teaching anxiety dreams, but mine followed me even after stepping down from active faculty status. You can take the girl out of the classroom but you can’t take the classroom out of the girl. Particularly late at night when she’s asleep.

As soon as that kind of dream begins, I recognize its well-worn form. Either I can’t find the building or the classroom or my notes and it’s past the hour. The dreams recur — always desperate, harrowing and unforgiving.

So imagine my surprise the other night when, in the midst of a teaching dream, this is what happened. I was comfortably on time in the classroom. Every seat was filled. The lesson had to do with a philosopher who showed the influence of Plato. Accordingly, I pitched into an explanation of Plato, quoting A. N. Whitehead’s claim that all of Western philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato!

Turning to the blackboard, I wrote “Plato” at the left end and began, with fervent enthusiasm, to draw the timeline on which Plato’s influence had played out across the centuries. What I drew looked like a diagrammed sentence, with a straight line across the blackboard between subject at one end and predicate at the other, while dependent clauses and subclauses showed the lineage of influence in all its complexity.

Meanwhile, a couple of girls stood up to tell me that they had to leave. It was four o’clock on Friday and they needed to start getting ready for Shabbat (the Jewish sabbath).

Instantly I said that this was more important than their premature preparations for Shabbat and they should sit down again. They did. Without protest or back talk.

Returning to Plato and his impact on philosophy, I began to wax more and more eloquent as I unfolded its intricacies. Lines of influence that might have appeared too obscure to cite, or blocked by distractions, became a transparent, flowing stream, gaining momentum and breadth as I spoke.

There was a second interruption. A man in workman’s overalls stood up and said he had to leave because he was due to drill some steel girders.

“No!” I said instantly. “Plato is more important than steel girders.” Several students stood up and spoke in support and appreciation of this classroom hour. The alarm rang at last, bringing to a close my most (my only) successful teaching dream.

It was Saturday morning. Time to get up for Bible study, of the Torah or Pentateuch. Jews all over the world study the same Torah verses at the same time of the Jewish calendar year. Today it would be the verses in Numbers 16 through 18, which describe a series of popular rebellions against the leadership of Moses and his brother Aaron. I had a pretty clear idea of what I would have to say, if I said anything, when it came my turn in the discussion, as well as a sense that I’d be going against the consensus.

We are a Reform congregation. That’s the most liberal of the denominations, so discussions of the Bible often draw on examples from psychology, sociology, group dynamics, management skills and so forth. Since Hebrew scripture puts a lot of that kind of material in front of the reader, it is feasible to read it entirely in terms of such on-the-ground, empirical categories.

I don’t read it that way. I try to take it on its own terms, as a book that reports the doings of human beings in actual historical settings as they live out their ongoing relationship to a real God who created the world and cares what they do. Whether or not the events reported actually happened is an empirical question, hard to settle from 3,000 years down the road. But the events are reported as if they happened. These are not stories about gods and heroes, like Homer’s Iliad or India’s Mahabarata. Of all the sacred scriptures I know, this is the one most explicitly historical. To my mind, you can learn more if you read it as it was intended to be read.

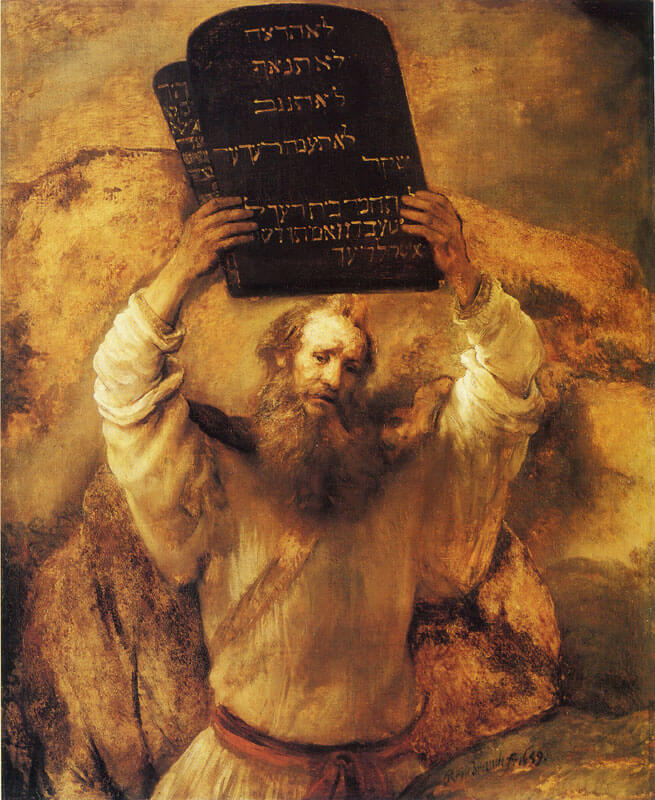

In the verses we were to discuss, a series of rebellions confronts Moses and his brother Aaron. This is the leadership that has already guided the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt, taken them through a body of water that parted before them but drowned the Egyptians coming after them, fed them in the wilderness, given them the ten commandments as well as a body of laws sufficient to hold them together in the Land Promised to them at the end of their journey. By divine intervention — visible, audible and palpable to all who were involved — this has been made feasible, with Moses acting as mediator between the Israelites and the God who has singled them out for His purposes.

These events form the shared experience of thousands of people whose incessant groaning discomfort and despair is minutely recorded – not redacted to produce a patriotic epic.

The rebellions reported in Numbers 16 to 18 take place after these and more providential interventions have occurred for all to see. The rebels are destroyed in ways that no ordinary man or woman could bring about, nor is theirs a natural death. In the face of unmistakable evidence of divine intervention, the people blame Moses for the death of the rebels. In terms of the story as told, it’s a lie — an obvious lie.

Why do they do it? Why not just give up, shut up, get into line behind the leader God has obviously singled out for the job? They don’t – because what they are suffering from is not ordinary wounded pride or frustrated ambition. From what, then?

Spiritual envy.

It’s a malady not classified in our contemporary psychologies. Yet, from the beginning of Biblical history, it motivates the first fratricide and much else recorded in that book. History spiritually considered (which is how the Bible looks at history) is pocked with incidents of spiritual envy.

This was roughly what I said when it came my turn to pitch in at our zoom Torah study. It seemed to make less-than-zero impression. People continued with their social and psycho-political analogies to the end of the hour. Did I go on too long? Just to retell the whole story (longer than what I’ve cited here) under this lens allowed no time for any tactful softenings. But clearly, I hadn’t been persuasive.

I remembered my pre-dawn dream where I had stood fast for the overwhelming gift of Plato, refusing to be distracted by those who made as if to leave. In the dream, the effect had been a wholly persuasive immersion.

It was like a happy ending that came before the actual event – while the actual event lacked any sign of effectiveness or resolution. And yet in real life, I had told the truth about the text just as, in the dream, about a different text.

Truth is one thing. Persuasiveness is quite another.

But in the dream

They were the same thing.