On Myth

With our unrestricted desire to make sense of experience, we humans—bodily, situated, spiritual—find ourselves presented with a staggering challenge: figure out what this cosmos is that we are involved in. Or rather, figure out as much of it as we can. And why we are participating in it. And what we are supposed to do, for heaven’s sake, on the basis of what we come to know.

And—do all this honestly: that is, with as little self-deception as possible, and with a readiness to correct judgments that we learn to have been mistakes.

To take up this task in our peculiar individual ways, whoever we are and however we’ve been situated, we have to gather what’s up from all the clues that the cosmos has on offer. Those clues include, not so incidentally, what has been done and spoken and written by persons as a result of extraordinary experiences of identity and communion with the ground of being in which we participate: actions and sayings and writings viewed as “inspired” or “revelatory.” How can we bring the meaning of those kinds of clues into our embrace?

Perhaps, initially, by viewing our human situation through “ancient” eyes—imagining how matters looked to early humans.

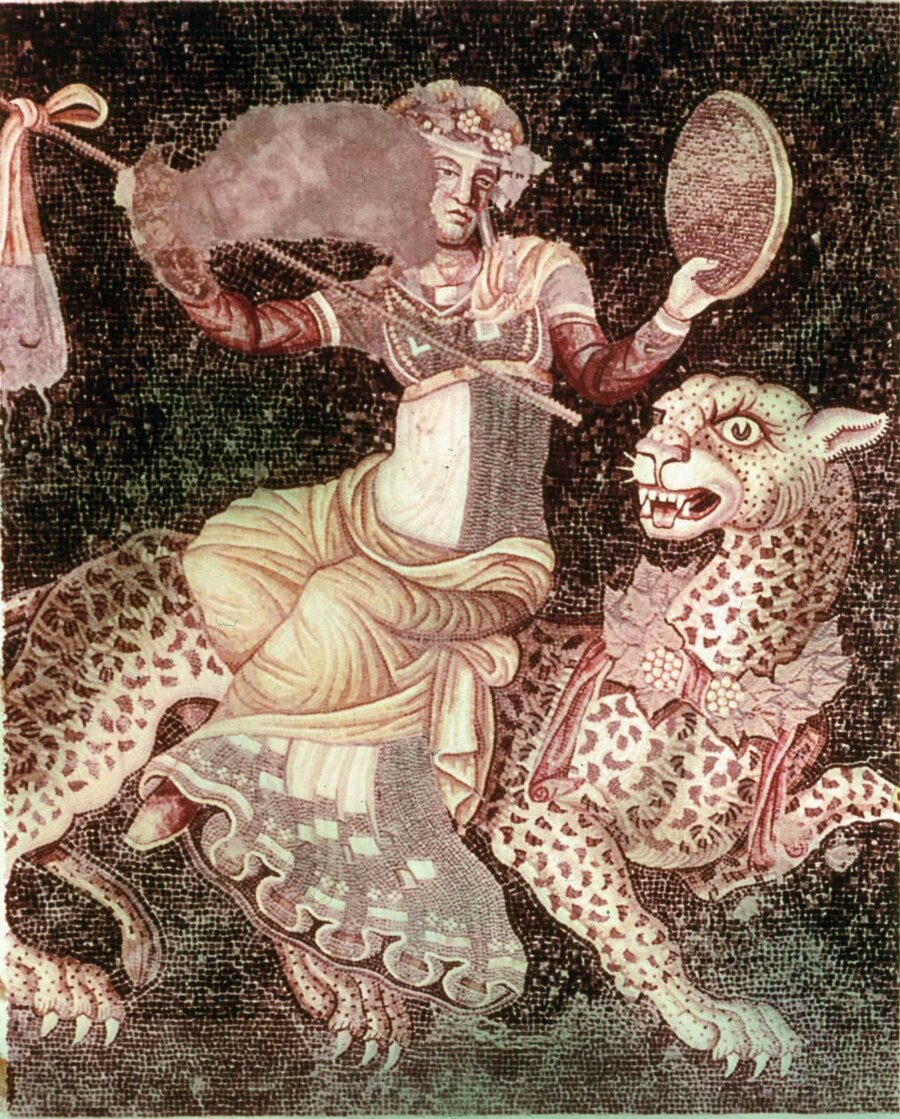

First, imagining our perspectives and our understanding of things primally, there is the obvious fact that everything that is, is (by definition) a part of the Whole of reality: all things are bound up with all other things. Which means that the beyond-human, “sacred” powers that move the heavenly objects, turn the seasons, drive plant life (“The force that through the green fuse drives the flower”), animal actions, fertility cycles—and that cause such startling events as earthquakes and rainbows and volcanic explosions and eclipses—are, in some way, involved with, one with, observable things, live in them, show themselves through them, originate them, and accompany them in disease, disaster, and death.

Why—it was asked by all ancients—are things the way they are? Why does the sun rise & move across the sky? How does rain make plants grow? What is the source of a toothache? The answers must lie most basically, it seemed obvious, in those powers beyond us (after all, we didn’t set these matters in motion) that are ultimately responsible for the order of things, and which are regarded as sacred for just that reason: gods and goddesses, and everything else that is a source of sacred power and intent. And it would be natural to think: we’d better align ourselves with these powers. Not just so as not to suffer from “the displeasure of the gods,” but above all for society and human activity to be in harmony with the way the cosmos is—to be attuned with the powers revealed in, and as, the cosmos.

Now, our human desire to understand allows us—requires us—to feel and think and express ourselves and communicate to others, about these matters in which we are intimately involved. And the basic language of such expression is symbols: enacted and portrayed complexes of expressive images that well up from the depths of our rootedness in the cosmos, images haunted by emotion, which are retained and accumulated and venerated because they are convincing in their expression about what it means to exist in the cosmic process.

So, we gesture or dance or daub or construct or speak or sing these symbols, again and again. Symbols of song and dance and picture eventually become elaborate tales. And tales are gathered so as to construct inspiring and comforting shelters of culture. They satisfy our felt understanding (such as it is) as to what this awesome, terrifying, joyful, sorrowful journey of participating in the cosmos actually appears to be about.

Elemental cosmic symbols and tales are all related to each other, since each is felt to have sprung necessarily from the sacred depths of the cosmos itself (from the “community of being” that is the mutual involvement of all things). These make up for different societies the crucial, cosmos-interpreting myths.

Because such myths weave, out of innumerable fibers, fabrics that overarchingly mediate the meaning and order of the cosmos for human groups, and let their members find meaning-making adjustment within it, they make up together a foundational “style of truth” (Voegelin). Ancient myths (sometimes called cosmological myths) reveal the truth of the human situation.

Ancient or cosmological myth proves, however, to be an inherently vulnerable and unstable style of truth—an odd thing to say, it would seem, about the manner in which humans from original times made the cosmos understandable to themselves. But in fact, as history has shown, ancient myth was susceptible to being undermined, eroded, and finally dismissed as the “style of truth” that is most convincing as a way for people to recognize and communicate the order of the cosmos, together with the purposes of their situation in it.

What was it that finally touched the vulnerabilities of the ancient myth, weakening their power to convince and console?

It was the ongoing discoveries on the part of human inquiry which in various civilizations identified the sacred ground of reality as transcendent—as non-imaginable, beyond language, beyond symbolic representation. These discoveries—in the West and in the East—introduced an imaginal and conceptual differentiation between the transcendent ground of being (the Tao, Brahman, the Form of the Good, Jehovah, God the Father), on the one hand, and the “world” (that is, everything not transcendent), on the other.

This “differentiating” between “world-transcending-ground-of-being” and “world-of-things-in-space-and-time” unfolded over centuries, beginning during the first millennium BCE, in diverse cultures, distinct languages, and differing manners. But everywhere it spread—and it did so with varying degrees of rapidity and thoroughness—it was antagonistic to and destructive of the “truth” of ancient, cosmological myth. Because now, divine or sacred ultimacy—the essence of all “beyond-human powers”—had been found to be other than worldly processes, celestial objects, forces, places, animals, kings. The disempowering of gods and goddesses had begun. They remained as potencies in the sacred imaginations and religious practices of peoples; but increasingly, they became recognized to be merely transparencies for the invisible, transcendent ground of being lying “beyond” the world and all its elements.

(This grove of trees, this desert canyon, can feel sacred to you. But if so, the degree of immediate sacred fullness felt by ancient peoples is still not yours; because your mind has been made aware, like it or not, of the fact that ultimate sacred being is utterly placeless and timeless.)

The reality of transcendence, once revealed, disturbed everything. The ancient myths that once was the cosmos telling the truth of itself became mere legends, paintings, figures, dreams—and finally, tourism for those wanting to feel connection with a ruptured or recondite enchantment.

The erosion of the power of cosmological myth did not, however, signal the obsolescence of “myth” (understood as “symbols and tales that truly mediate the meaning of the sacred”).

Myth remained crucial: because human beings always need feeling-symbols, and evocative tales, that illuminate and guide our connection with the transcendent Mystery in whose power we originated and with whose perfection and radiating meaning we still long to be in harmony. Thus the drawn-out experiences wherein transcendent reality was discovered and revealed gave birth to new kinds of myth, myths that tell stories about the soul that explicitly participates in transcendence: a story of personhood that describes a sharing in a “beyond” of world. (Reincarnation? Resurrection?)

The differentiated myths that are intrinsic elements of Hinduism, of Buddhism, of Judaism, of Christianity, of Islam—all are understood within each tradition, of course, to be grounded in extraordinary personal experiences of identity and communion with the ground of being in which humans participate. That is, transcendent being itself is understood to speak in and through them.

But if post-differentiation myth has, for many, turned to ashes—what then?