On the Purity of Music

Music is often claimed to be—and valued as—a “pure” art, one detached from the referents to the external world that we find in painting or literature. Music is thought to be abstract, dealing in patterns of sound that have a meaning independent of the meanings of verbal language.

True, when music is married to a text, the music is assumed to express and enhance the meaning of the text (how, exactly, it does this might again be hard to specify). But when it comes to instrumental music, and particularly instrumental music that has no “program” or descriptive intent, one can rarely if ever assign to it an exact meaning. There may be clues in the expressive or rhetorical shape of the music—everyone can tell that the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth is a drama, for instance—but these are no more than general emotional or psychological states that may be suggested by the notes. Music, at heart, deals in indefinable moods and states of the soul. Music’s “vagueness” and subjectivity are its very strength, allowing the listener to interpret or react to it as he wishes.

Being mysterious and hard to pin down, music is typically left alone by writers who deal in the “world of ideas”—general or intellectual history, sociopolitical matters, and the like. They find easier fodder in visual art and literature because those arts deal more or less with concrete things in the world. As a result, music is perhaps less filled with commentary and verbal clutter than other areas of intellectual life, and that is all to the better.

The idea that music is “pure” or “absolute” was stressed in the nineteenth century. “Music for its own sake” (like “art for art’s sake”) was a popular concept with musical aestheticians such as the critic Eduard Hanslick, one of Brahms’ admirers. The idea was that music was not (or should not be) dependent on anything extrinsic to it, did not exist for the sake of anything else, and was its own end.

To be sure, music has been used for ends outside of itself, including ideological ones. One thinks of “Soviet realist” music in communist Russia, or the Nazis’ appropriation of Wagner. The serious music lover, one who loves the art for its own sake, will regard these instances as a misuse or perversion of music. One still finds instances of music being harnessed to other ends. There used to be a fad for parents to play Mozart for their infants under the assumption that it would make them smart. Conservative journalist Jay Nordlinger writes of the contemporary trend for what he calls “green pieces,” or pieces of music tied to an environmentalist message.

Much pop music of recent times has less to do with the serious appreciation of music in its various dimensions—melody, harmony, rhythm—than with the manipulation of human emotions and instincts for commercial ends. By contrast, the closer music comes to existing for its own sake and for the sake of an appreciation of purely musical qualities—and the expression of human emotions through musical means—the more it can be said to be serious or artistic music. Hence, the more it approaches perfection as music.

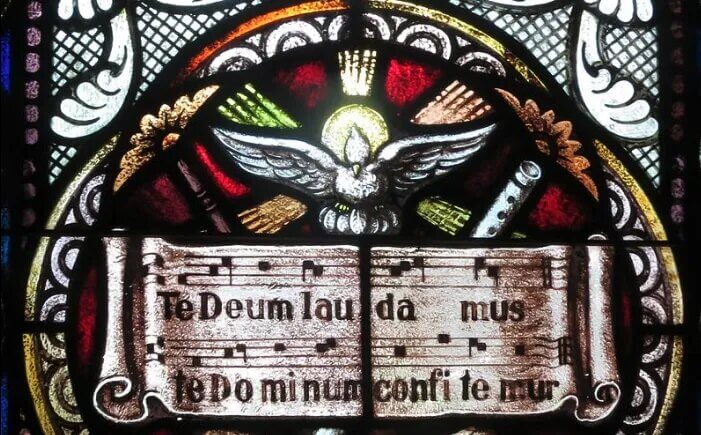

Granted, a lot of music is for voices and comes with a text, and some of this repertoire is more about the text than about the music. Hymns and liturgical song have their reason for being in the words. The purpose of the music is to carry and intensify the words so that the song becomes an intensified prayer. What we are talking about in this essay, however, is what might be called purely artistic music, which exists for the sake of aesthetic enjoyment and contemplation.

Even in the case of some texted music, one can mentally separate the music from the words and evaluate it on its own terms. The melody of a hymn can be considered in its inherent aesthetic qualities, and many a composer has quoted a chorale tune or Gregorian chant in the absence of the words.

We are still left with the fact that music, considered purely as music, is absolute (“being fully or perfectly as indicated; complete; perfect”) and not tied to anything else, in the way that figurative art or literature are tied to subject matter. Music is not inherently involved or interpenetrated with anything in the immediate everyday world. The “subject matter” of a musical piece is the musical themes, the harmony, the melody, the rhythm, and all the other musical elements that the composer organizes and develops. This even applies in cases of program music, where the composer has written an instrumental piece around a storyline or series of images. The music is still simply music, in a sense that we cannot say of a painting of still life that it is “simply” daubs of paint on canvas. (“Abstract” art is of course a different story.)

Although music is a “pure” art, this is not to say that it is, or should be, a mathematical abstraction devoid of emotional significance—as, for example, serialist composers in the 20th century tended to treat it. Music certainly has powerful emotional qualities, qualities rooted in its very acoustic structure which relates to our souls and bodies. Philosophers going back to Plato have known and written about this, and it cannot well be denied. Even so, one can at the same time affirm that music has expressive content and that it is not stringently tied to anything concrete or extra-musical. It exists in its own world and is subject to its own rules and laws, which are not the rules and laws of literature or philosophy.

Further, the fact that music is “pure” or “serious” or “artistic” does not say anything about its particular emotional character. It does not exclude the possibility of its being lighthearted, entertaining, amusing, or diverting. Far from it. These are aesthetic qualities that any form of art may project. Art is for enjoyment. It should foster pleasure and beauty, even in the midst of expressing sorrow, anger, or tragic emotions.

Nor am I suggesting that music can’t be profitably related to other areas of human life—to history, to religion, to the other arts. On the contrary, I welcome such interdisciplinary efforts. I would only suggest that analogies between music and other human affairs go only so far. For example, many discussions of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony center on the personality and activities of Napoleon and the influence these might have had on the composer. But an understanding of Napoleon will not get you straight to an appreciation of the symphony, which exists in its own realm apart from the material-historical-political world which may have conditioned it.

Least of all am I suggesting that music is detached from life but somehow floats above it as some Platonic ideal. On the contrary, music is and should be interwoven with everyday life. Music after all is made from the stuff of matter and physical science, from sound waves to wood and brass.

My idea is simply that music is, intrinsically and primarily, itself, and that it is singular among the arts. Music exists apart from other areas of human endeavor owing to its nonverbal, non-dialectical character and immaterial essence. In the words of musicologist Jan Swafford, music is “a language of the spirit beyond words.” Words are much too specific for what music expresses. Music can be said to have its own inner “logic” and to make statements, but such statements are entirely outside the world of verbal language.

Music’s purity and detachment from other fields of activity means that it is has a purifying effect on the soul. It frees us from captivity to the world of things and from history, ideology, and politics, and raises us to an experience of pure emotional and spiritual states. Artistic music is not a means to an end, but something we enjoy for its own sake.

Perhaps this is the sense in which music can be called a liberal (free, not tied to any practical purpose) art. With its strong theoretical backbone, its rootedness in science and acoustics, it deserves to be called a liberal art. It is undoubtedly an object of the intellect, and the elements that make it up can be studied in the abstract.

Yet in its fully realized state, music is a practical art. The notes on the page are only potential music; they do not become actual until they are sounded. So it is that music performance, on all the instruments and the human voice, is the subject of academic courses of study. Any working musician will tell you that music is physical labor demanding energy and bodily stamina. And yet the “hard work” of music is for the sake of an activity of pure “uselessness,” leisure, and contemplation. Music is ultimately mysterious and inexplicable, and thus a signal activity for free human beings.