Philosophy and Liberty in a Commercial Age

“Of all these [Gallic tribes], the Belgae are the strongest, because the provinces are farthest removed from culture and civilization, and not least because merchants often come to them and bring things that belong to the enervated minds, and they are nearest to the Germans, who live beyond the Rhine, with whom they are constantly at war.”[1]

So writes Caesar in the opening lines of his Bellum Gallicum. The Belgae proved the most resistant of the Gallic tribes because they retained a sort of savagery–a prejudice–which had been cultivated by their geographic and political position–their climate and terrain, mores and manners. Their spirit emerged from both the accidental qualities of their region and the constant state of war in which they found themselves. And perhaps just as importantly, their spirit was not stifled by dealings with foreigners in commerce and trade, which Caesar recognizes as enervating in their effect.[2]

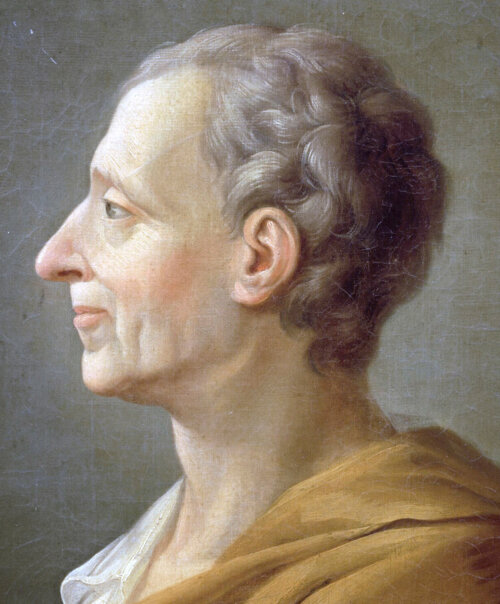

In Caesar’s terms, Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu’s political vision is one of universal enervation. Like Caesar, he is attuned to the political and psychological effects of commerce, but his response is at odds with Caesar’s. For he writes in a different age–a post-Christian age. Caesar’s Belgae did what they had to do in order to survive, to win. Montesquieu would have the national leaders of his time pursue the same end–victory–though the means are fundamentally different. Yet Montesquieu does not praise commerce so openly; indeed, he does not even approach the matter explicitly until over halfway through the substantial tome that is The Spirit of the Laws. Yet this moment should give the reader pause: for Montesquieu tells the reader in his preface that the work has an intentional design.

Commerce has three important effects on mankind: it alters the human psyche, it alters political life, and it causes the rapid development of technology, which accelerates the former two effects in turn. With respect to the first, Montesquieu argues that “commerce cures destructive prejudices,” going so far as to add that “everywhere there are gentle mores, there is commerce, and everywhere there is commerce, there are gentle mores.” And it is Montesquieu’s very project to cure men of harsh mores. At the outset of the Spirit of the Laws, he tells his reader: “I would consider myself the happiest of mortals if I could make it so that men were able to cure themselves of their prejudices.” Prejudice, in his view, is at the root of human delusion; for it is not simply a lack of awareness generally, but is precisely that which “makes one unaware of oneself.” Prejudice causes one to lack self-knowledge. It makes man unfree, opposed to the new conception of liberty. Commerce, then, is a means by which one might come to acquire self-knowledge; for it would drag one out of the darkness of savagery and into the light of freedom. Yet the curing of prejudices through commerce has come in a series of revolutions, which become more visible as political revolutions. Montesquieu therefore sees himself as a political philosopher par excellence, one who leads men to self-knowledge by setting down a model of government which will make man gentle and prepare him to “know his own nature when it is shown to him.” So, in his examination of climate, terrain, and commerce–which culminates in the exaltation of commerce as the new fundamental premise for which any legislator must account–Montesquieu reveals his two primary aims: to secure political liberty for the many, and philosophy for the few.

Commerce & Psychology

“Mores and manners,” Montesquieu tells us, “are usages that laws have not established, or that they have not been able, or have not wanted, to establish.” Lycurgus, Sparta’s famous lawgiver, wrongly treated mores and manners the same as he treated laws, believing that he could simply legislate them via the political art. Yet we are reassured that this mistake is very common: for “mores represent laws, and manners represent mores.” A legislator with true wisdom, on the other hand, would understand that mores and manners change rather slowly, and ought not to be radically altered by innovative laws that have no eye for the climate and terrain of a regime or the general spirit of a people. Yet a regime that aspires to success ought to make laws only after careful deliberation regarding the general spirit of a people. And for a post-Christian people, like those with whom Montesquieu believes he is dealing, commerce prepares certain individuals to best receive philosophy and others to achieve political liberty. It softens their political attachments and strengthens their proprietary attachments. Commerce is a means by which mores and manners might be altered.

Trade, in Montesquieu’s opinion, promotes harmony among nations, but it does not have precisely the same effect on individuals. Friendships become altered in some fundamental way. For, he writes, “there is traffic in all human activities and all moral virtues,” which “are done or given for money.” True friendship can hardly exist in such an environment; friendship of utility will thrive. Yet this is not a political problem; rather, it may actually promote peace. For commerce is the communication among people, and this communication corresponds with a reduction of barbarism, or blind attachment to one’s own. Friendships of the most loyal sort can lead to destructive prejudice or even war. Superstition and tribalism will thrive among people who do not partake in commercial life. Thus, loyalties will fall away and intense friendships cease, and men will instead have large networks of business partners–acquaintances with which one has similar interests.

The decline of Aristotle’s true friendship among individuals resulted from a new conception of justice among men. Justice will become calculative, “exact,” as Montesquieu calls it, directed towards self-interest and feeling no qualms about neglecting the interest of the other party. The result is what Rousseau would describe elsewhere as the bourgeois man. Yet alongside commerce comes increased communication: for “the more communicative peoples are, the more easily they change their manners, because each man is more a spectacle for another; one sees the singularities of individuals better.” Montesquieu takes up this theme later in the book, noting that “the history of commerce is that of communication among peoples.” For in communication lies self-knowledge; dialogue is possible only within the parameters of political life, and without dialogue, there can be no self-knowledge. With increased communication, despite the fact that much of it is instrumental, comes a greater opportunity for philosophy, as the philosopher will more easily discover nature–that which remains constant–by encountering the various ways of life.

And it is a new conception of justice based upon contractual obligation that leads to a political revolution. Justice is founded upon what was previously considered to be the cause of injustice: self-interest. By pursuing wealth within the purview of the established and moderate laws, one can contribute to the good of the whole–a better and more reliable mechanism for the pursuit of civic harmony than the ancient conception of the common good. This new political science is possible insofar as the power of man over nature has grown. No longer are men simply subject to the whims of climate and terrain. Nonetheless, one must never tamper too much with the natural spirit of a people. For “many things govern men: climate, religion, laws, the maxims of the government, examples of past things, mores, and manners; a general spirit is formed as a result.” The general spirit emerges from a wide array of variables, and cannot simply be scientifically managed or altered. But it can be tweaked: for Montesquieu writes that “nature and climate almost alone dominate savages; manners govern the Chinese; laws tyrannize Japan; in former times mores set the tone in Lacedaemonia; in Rome it was set by the maxims of government and the ancient mores.”

Further, following Mandeville, Montesquieu believes that the very success of the human race depends directly on the ability to channel human passions properly. “Society,” Rica tells the reader in the Persian Letters, “is founded on mutual advantage.” For this reason, Montesquieu rejects the notion that the average man is capable of understanding what is good and therefore of being good, at least insofar as Aristotle understood the good. Rather than aspire to excellence, men must aspire to political liberty. In the backdrop of all of Montesquieu’s thought lies his fundamentally modern view of the cosmic order: for “all men together…are only a tenuous and minute atom.” Yet ultimately commerce will demand a comparison of different ways of life, causing men to break out of their parochial manners and mores, destroying their prejudices and preparing them for enlightenment. Philosophy, then, is sustained by cosmopolitanism, and cosmopolitanism arises from commerce.

Commerce & Politics

“The great enterprises of the traders,” Montesquieu writes, “are always necessarily mixed with public business.” Commerce, therefore, has not only a transformative effect on the souls of men, but on their political regimes in concrete ways. The new regime must account for the new direction of the world, and it must understand the basic premise of the new political science. For Montesquieu, this means a principled rejection of monarchy as a viable form of government. No longer can we trust the virtue politics of Aristotle, what one might call a politics of being in the sense that one must actually be virtuous and a polity must be just. Rather, Montesquieu promotes a politics of seeming, of giving men a proper opinion of the prospects of their own prosperity, encouraging them by effect to “undertake everything” in the belief that “what one has acquired is secure.” The wise legislator will know that, in order to secure political liberty, he must shape the laws of the regime so as to promote commercial life within the bounds of the possible given the people and the land.

Politically, commerce promotes international concord and domestic liberty. Montesquieu writes that “the spirit of commerce unites nations” by softening the mores, as noted above, but also by giving all involved in contractual obligations a sort of common interest. The people of different nations will learn about each other through concord and travels abroad. Men will be enlightened by the spread of “knowledge of the mores of all nations everywhere.” The nature of commerce is to “lead to peace,” each nation having become “reciprocally dependent” on the other, binding together contractual unions by a mutual need.

As such the future is necessarily cosmopolitan, because it leads to the exchange of ideas on an international basis. Great business enterprises will replace great wars. Politically, this means that monarchy is no longer viable as a form of government. Monarchy, which is moved by honor and ties of personal loyalty, tends toward warfare, an expensive and prejudiced proposition. The expense of war burdens the people and will force the monarch to aggressively tax his people, damaging in effect their liberty. Therefore, “commercial enterprises are not for monarchies,” but are instead “for the government by many.”

Rather than monarchy, the best regime in what Montesquieu calls the post-Christian age is the commercial republic, supported by laws which give men the illusion of security. Whereas in a monarchy, certain classes of men are not permitted to engage in commerce, in a commercial republic, the possibility of prosperity is open to all. Montesquieu writes, “it is against the spirit of commerce for the nobility to engage in it in a monarchy” because it is considered dishonorable. In England, where the nobility had become commercial, the monarchy was severely weakened.

So Montesquieu makes commerce serve the dual ends of liberty and philosophy. The age of commercial republicanism has arrived; for such a regime will have a pliable nature–one which can adapt to the flux of the commercial world. Men will also accordingly be more fit for liberty. Since commerce cures men of their destructive prejudices that cloud their judgment and cause them to live in blindness, it frees them. Commerce, therefore, causes liberty, which pertains directly to following the laws–of which there are many in a commercial state. And as one learns of oneself by communication with others, so a people learns of itself by communication with other peoples. It follows, then, that the laws of a regime, insofar as the parameters of climate, terrain, and the general spirit of the people allow, ought to “put the fewest obstacles in the way of commerce” that can possibly be admitted.

Commerce & Technology

“The compass,” Montesquieu tells us “opened the universe, so to speak.” Montesquieu sees that the technological age is already upon the human race, which has been inspired to innovate by its very vanity. Science, that is, philosophy of a certain sort, has come to the aid of the many, turning from contemplation of the cosmos to the manipulation of man and the natural world. Distance has been conquered; man can, for the first time, see the entirety of the globe–the very map of which Montesquieu initially inserted between the central chapters of his magnum opus. The history of commerce reveals the development of technology towards the liberation and enlightenment of mankind.

Technology, Montesquieu argues, has created radical new political opportunities. It is even capable of reshaping the earth to better suit the demands of human life and the innovation of luxuries. According to Montesquieu, “men, by their care and their good laws, have made the earth more fit to be their home. We see rivers flowing where there were lakes and marshes; it is a good that nature did not make, but which is maintained by nature.” And though Montesquieu does not speak of the conquest of nature, it is notable that war is replaced by commerce, one form of conquest for another. The new form of conquest requires a new form of laws, what Montesquieu calls “a more extensive code of laws” tailored for “a people attached to commerce and the sea,” whose time to rule has come, rather than the people “satisfied to cultivate their land.” One sees in this statement a development of his earlier claim that laws

should be related to the physical aspect of the country; to the climate, be it freezing, torrid, or temperate; to the properties of the terrain, its location and extent; to the way of life of the peoples, be they plowmen, hunters, or herdsmen…

Quite notably, he makes no mention of commerce in the early part of the book, wherein one might come to believe that man lives merely under the sway of inherited customs, climate, and terrain. Montesquieu also appears to be remaining in the prior philosophical tradition while hiding away his own innovation in the center of his work. It is only following the world map that Montesquieu introduces commerce, and finally the triumph of the English people as the most moderate and commercially-oriented state.

Nonetheless, climate and terrain retain an essential place in Montesquieu’s understanding of political life. For, he tells us, the ancients knew only a few Mediterranean ports, all constricted to the same general region. There could be no exchange of things that could not be obtained from the same general climate. “Today,” however, “the commerce of Europe is principally carried on from north to south,” thereby spreading commodities that would not be available without the traveling of great distances. And so seafaring is the great technological development of Montesquieu’s time, and this significant fact is directly tied to the success of the English. Much to Machiavelli’s dismay, no longer will the nation of landholders rule, but a nation of merchants and artisans: liberty is maximized among those with no home. Men who do not cultivate the land “enjoy great liberty: for, as they do not cultivate the land, they are not attached to it.”

To be sure, farmers once formed the backbone of republics. Montesquieu notes as much in his account of Rome. But this was nothing more than an historical necessity. Through agriculture, money was introduced, forming the beginning of a fundamental dialectic between necessity and knowledge, each leading to the other in turn, causing numerous commercial revolutions throughout history. These revolutions move social conditions toward favoring men without homes–that is, merchants–can move themselves to a land where laws are fairer for money making and where they may secure the opinion of security.

Toward a Commercial Globe

Looking back on the decline of the ancient world the historian Ammianus Marcellinus saw his Rome collapsing under the weight of its own urbane decadence. The elite class, obsessed with cultivating for themselves the highest opinion in the eyes of others, forsook philosophy, thinking, valor, and austere virtue for the appearance of those things. In their place, one sees only banquets, vanity, moneymaking, and debauchery.

Yet for Montesquieu, Rome’s collapse cannot be assigned in principle to the reasons suggested by Marcellinus. If it were simply institutionally sound, the softening of mores might have indeed been turned to great use for the empire. The fall of Rome has more perhaps to do with an alteration of its general spirit by its own success. Yet no longer is the old warlike republicanism viable in Montesquieu’s view, even if it were possible to attain. He is not shy about the fact that “the Carthaginians, masters of commerce in gold and silver” would in his time defeat the Romans, “who cared only for land troops, whose spirit made them stand ever firm, fight in one place, and die there.” A new age calls for a political science altogether new. For “commerce… wanders across the earth,” reigning “where one used to see only deserted places, seas, and rocks; there where it used to reign are now only deserted places.” It can be stifled but never stopped, slowed but never conquered.