Poe’s Psychic-Atomist Critique of Wayward Modernity

Many people know of the “Big Bang” or singularity theory of cosmic origin, but far fewer know that the author of the singularity theory was a Belgian scientist-priest, Georges Lemaître (1894 – 1966), who, in addition to his work in mathematics and physics, served as an artillery officer in the Belgian Army in World War I. The name Lemaître rarely crops up in textbook discussions of the singularity theory although it does appear in the Introduction to the Wikipedia article on that topic. The name of Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849) goes absent in the Wikipedia article about Lemaître, where it would in fact assume some relevance, an observation that one can extend to Lemaître’s own published writings. Lemaître enjoyed broad cultivation. A typical Jesuit, he knew the humanities and arts as well as the sciences. He could hardly have remained unaware of Poe’s self-described masterpiece, the “prose-poem” Eureka (1848), which Charles Baudelaire had translated into French in 1863. To Poe belongs the actual invention of what Lemaître would call, in a popularizing essay of that name, “The Primeval Atom” (1946). Even the details of “The Primeval Atom” find anticipation in Eureka, which formed the basis of lectures that Poe gave to bewildered audiences in the last year of his life. One wonders whether Lemaître’s omission of Poe’s name was calculatedly prudential. Disclosing the inspiration of Poe’s cosmology would no doubt have occasioned supercilious commentary. Better not to complicate the issue by tying the theory to a bizarre literary text by a known eccentric, full of heavy satire and laced throughout with manifold irony. Better not to adduce the author of “The Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Masque of Red Death.”

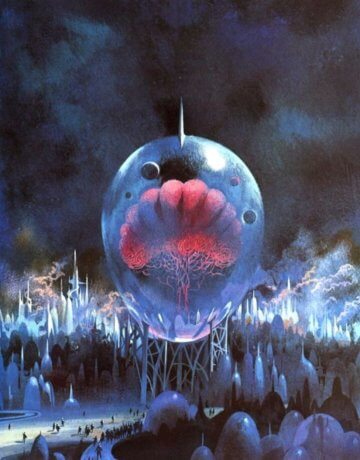

Richard M. Powers (1921 – 1996) – Untitled Abstraction (1979)

PART ONE. Eureka, whose second subtitle after “A Prose Poem” is “An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe,” has a retro-active relation to Poe’s other work although Poe composed it simultaneously with his late story “Mellonta Tauta,” in 1848. Eureka and “Mellonta Tauta” share a number of devices and themes: For example, transcribing a letter penned a full millennium in the future, in which the epistolarian satirizes the partiality of knowledge in a past and primitive age; and in which again he addresses, now with levity and now with gravity, matters of metaphysics, epistemology, and cosmology. Poe’s work being of a piece, however, the reader familiar with the totality of the Poe-esque authorship will readily perceive that the “prose poem” takes up threads first exposed in earlier entries of the Baltimorean’s oeuvre and completes them. While Eureka takes as its thesis “the Universe,” and thus qualifies itself mainly a cosmological disquisition, its range of topics stretches wide. “Mellonta Tauta” declares no topic, but rummages among a seemingly arbitrary congeries of topics, related only associatively, in the flighty mind of the letter-writer. In his temporal displacement, in both Eureka and “Mellonta Tauta,” Poe achieves symmetry in points of view. Modernity considers itself as the overcoming of medievality, which commences around the year 1000; but the year 2848 considers itself as belonging to an era that has recovered from the intellectual fallacies that disabled the mind during a period beginning a thousand years previously, the impression of which still tells. Eureka takes its title from Archimedes, the Syracusiac physicist who, when he suddenly intuited the principle of buoyancy from his bath, shouted, “I have found it,” but in Greek, thus uttering the titular tri-syllable that Poe borrows. Intuition figures prominently in both texts.

Poe begins Eureka with a confession of inadequacy: “It is with humility really unassumed – it is with a sentiment even of awe – that I pen the opening sentence of this work; for of all conceivable subjects I approach the reader with the most solemn – the most comprehensive – the most difficult – the most august.” When discoursing on matters “Physical, Metaphysical and Mathematical”; when directing his inquiry to “the Material and Spiritual Universe,” to “its Essence, its Origin, its Creation, its Present Condition and its Destiny” – this strikes Poe as indeed the only permissible attitude. In its blandness, what goes by the name of science fails to connect with the sublimity of nature, which is as much unseen as seen. Science accumulates facts and arranges them in neat tables. It reduces Nature to a description of phenomena. Science uses the word theory, but according to Poe, or rather to his future letter-writer, the meaning of theory remains foreign to contemporary or Nineteenth Century thought, but this is to leap ahead of Poe’s exposition. Poe writes: “And now, before proceeding to our subject proper, let me beg the reader’s attention to an extract or two from a somewhat remarkable letter, which appears to have been found corked in a bottle and floating on the Mare Tenebrarum – an ocean well described by the Nubian geographer, Ptolemy Hephestion, but little frequented in modern days unless by the Transcendentalists and some other divers for crotchets.” The sentence exemplifies the density of Poe’s prose, and the complexity of irony, satire, and critical acuity that dwells within his carefully crafted periods. Mare Tenebrarum, for example, an archaic denominator of the unexplored South Atlantic, constitutes a self-reference to “MS. Found in a Bottle” (1833) and The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838), two early publications by Poe that point ahead to Eureka and “Mellonta Tauta.” The reference to “the Transcendentalists” implicates not only the American school of thought of that name but also the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, whom the letter-writer invokes, if somewhat obliquely.

The Eureka letter concerns itself with the methods by which the moderns – or, to him, the ancients, the men of Poe’s Nineteenth Century – sought to arrive at truths metaphysical and thus to set the foundation for their world view. These men of a millennium ago inherited, from even earlier in history, two erroneous views. From “the night of Time” a “Turkish philosopher,” one “Aries… surnamed Tottle” or “the Ram,” postulated the dogma of “what was termed the deductive or à priori philosophy.” According to the Ram, the path to certain knowledge commenced “with what he maintained to be axioms, or self-evident truths.” For the letter-writer, Aristotle constructed a closed, a purely syllogistic game. Thus “his most illustrious disciples were one Tuclid, a geometrician… and one Kant, a Dutchman, the originator of that species of Transcendentalism which, with the change merely of a C for a K, now bears his peculiar name.” Then came “Hog” or “the Ettrick shepherd,” who insisted on “an entirely different system, which he called the à posteriori or inductive.” Whereas Aristotle founded the picture of nature on “noumena”; Hog (that is, Bacon) founded the same on “phenomena.” Hog at first displaced the Ram, but Hog’s immediate successors reconciled the two and put equal emphasis on deduction and induction, to the exclusion nevertheless of any third path. In the view of the letter-writer – which reflects the conviction of Poe – this exclusive alliance of deduction and induction “confined investigation to crawling” and to an endless accumulation of “facts” which could never actually consummate itself, or reach its goal. Mankind plodded along intellectually with the gait of a “tortoise.” What about the third path?

Alizey Khan (born 1988) – Crab Nebula (2012)

In Eureka and “Mellonta Tauta” the third path appears, not in codification but in praxis, in the achievement of Johannes Kepler, Poe’s scientific genius par excellence. After a complex traversal of the attitudes of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which the letter-writer, speaking no doubt for Poe, regards as stupefaction, the discussion comes around to the indices of Truth. “Is it not,” the missive asks, “an evidence of the mental slavery entailed upon those bigoted people by their Hogs and Rams, that in spite of the eternal prating of their savants about roads to Truth, none of them fell, even by accident, into what we now so distinctly perceive to be the broadest, the straightest and most available of all mere roads – the great thoroughfare – the majestic highway of the Consistent?” Indeed: “Is it not wonderful that they should have failed to deduce from the works of God the vitally momentous consideration that a perfect consistency can be nothing but an absolute truth?” To Kepler the enlightened owe their noetic liberation. Kepler, a great theoretician in the etymological meaning of the term, took cognizance of the whole rather than the parts. When he solved the problems afflicting the Copernican model of the universe, he did so through intuition: “Yes! –These vital laws Kepler guessed – that is to say, he imagined them.” If anyone had questioned Kepler how he arrived at his vision – that is, which route he had taken, Ramish or Hogish – his answer would have been: “I know nothing about routes – but I do know the machinery of the Universe… I grasped it with my soul – I reached it through mere dint of intuition.”

Having bushwhacked through Poe’s lapidary prose thus far, the reader will now be able to make sense of a bizarre figure in the opening paragraphs of Eureka before the quotation of the Mare Tenebrarum letter. How might the tourist, standing on the lip of Aetna, properly appreciate the wholeness of the scene? The answer – by spinning rapidly about on the pivot of his heel! Poe acknowledges the danger. The spinner could very easily precipitate himself into the caldera. Assuming good balance, however, the gyrating onlooker would have grasped Aetna and its surroundings as a panoramic totality, with his visionary self as the theatrical concentrum. Poe writes, apropos of epistemology, “We require something like a mental gyration on the heel.” Only by such could men make the minutiae of our cluttered worldview “vanish” and thereby have access to “the imperishable and priceless secrets of the Universe.” Mankind would rise, through such access, to the “cosmical family of Intelligences”; whereas mankind remains a diffident and tortoise-slow gatherer of facts and details. Poe judges the situation as not only intellectually, but also as morally deficient. In “Mellonta Tauta,” the correspondent assesses how, “It cannot be maintained… that by the crawling system the greatest amount of truth would be attained in any long series of ages, for the repression of imagination was an evil not to be compensated for by any superior certainty in the ancient modes of investigation.” People whose mental habit signals itself by “their eternal prattling about roads to Truth” are, in fact, “bigoted people” who “have failed to deduce from the works of God the vital fact that a perfect consistency must be an absolute truth!” Notice that, in adulation of “crawling,” men turn away from the divine principle. In Eureka, with these preliminaries out of the way, Poe launches his exposition of how the universe springs from a primordial Unity; how it consists of atoms and the void; and how, when repulsion exhausts itself, the cosmos will return, by attraction, to its hyper-mono-atomic form – only to begin again.

The discussion will return to relevant passages from Eureka as necessary, but for now those items of Poe’s authorship that articulate explicitly his little-appreciated critique of modernity will occupy the focus of attention. The explicit minded atomism of Eureka will prove itself to have functioned as an implicit basis for Poe’s analysis of things physical, metaphysical, political, cultural, and sociological from as early as the 1830s. Two classical sources, contradictory in themselves, serve Poe as models of the cosmological-psychological-sociological or psychic-atomist critique: The Timaeus of Plato and the Rerum Naturae of Lucretius. Both exemplify intellectual qualities that Poe admires, foremostly Imagination and Intuition. Poe will borrow from Plato the literary-dialogue model and the presumption of a minded cosmos that originates in the intention of a benevolent Creator; he will borrow from Lucretius the literary device of a first-person didactic exposition addressed to a specific but fictitious person and the regular recursion to a singular intuitive idea – the atomic substratum of everything that exists. Poe stands yet closer to Plato than to Lucretius, who rejected the minded cosmos hypothesis in favor of a materialist causality. “Mellonta Tauta,” so bound up with Eureka, will provide a good starting-point in the survey of Poe’s fiction. Poe endows on his epistolary narrative a Greek title. The two words mean, “These Things Shall Be,” and the story (or discourse – there is not much of a story) thus partakes in eschatology. The topic of “Last Things” circulates widely in Poe’s authorship from its commencement.

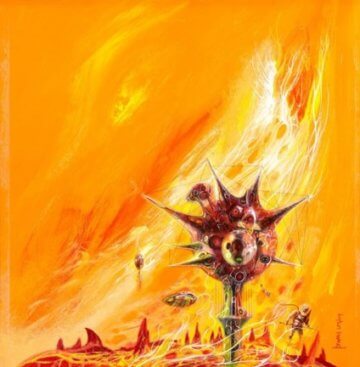

Paul Lehr (1930 – 1998) – Untitled (1978)

“Mellonta Tauta” depicts a dystopian future. Mankind has made the discovery of the epistemological third path, it is true, but this remains known only among an esoteric coterie. The year 2848 also exhibits malign traits that trace their origins to Poe’s time. Readers learn that massive overpopulation has thronged the world, leading to a diminished appreciation for the individual person. “Pundita,” Poe’s letter-writer, remarks how, traveling by balloon over the ocean, she witnessed a drag-rope knock a man from the deck of an overcrowded barge: “The man, of course, was not permitted to get on board again, and was soon out of sight, he and his life-preserver.” She then further describes the sacrificial principle of the socialism under which the global humanity exists. “I rejoice,” as she writes, no doubt with irony, “that we live in an age so enlightened that no such a thing as an individual is supposed to exist”; rather, “it is the mass for which the true Humanity cares.” These conditions began a thousand years ago, with the American or “Amriccan” Republic. Pundita might well be commenting on 2020 rather than 1848: “They started with the queerest idea conceivable… that all men are born free and equal – this in the very teeth of the laws of gradation so visibly impressed upon all things both in the moral and physical universe.” In the Amriccan Republic, “universal suffrage gave opportunity for fraudulent schemes, by means of which any desired number of votes might at any time be polled, without the possibility of prevention or even detection, by any party which should be merely villainous enough not to be ashamed of the fraud.”

Elsewhere in “Mellonta Tauta,” Poe has Pundita address the sins of the ancient tribe of “Knickerbockers.” The annals of the Knickerbockers tell of a giant named “Mob.” This Brobdingnagian “was… insolent, rapacious, [and] filthy”; he “had the gall of a bullock with the heart of a hyena and the brains of a peacock.” He ran wild, made much destruction, until he petered out, as mobs do. “Nevertheless, he had his uses, as everything has, however vile, and taught mankind a lesson which to this day it is in no danger of forgetting – never to run directly contrary to the natural analogies.” Analogy operates in “Mellonta Tauta” as it does in Platonic lore: Order finds its pattern in the celestial movements and in nature in general. Whatever flouts the pattern of order dooms itself to extinction. Pundita writes: “As for Republicanism no analogy could be found for it upon the face of the earth – unless we except the case of the ‘prairie dogs,’ an exception which seems to demonstrate, if anything, that democracy is a very admirable form of government – for dogs.” The satire must be understood in context and by analogy. When in Eureka Poe adduces the qualities of the primordial atom, he asserts that it has none, for “Unity is Nothingness.” Only in radial dispersion, prompted by the “Volition of God,” does the cosmos acquire qualities, including that of mind. The mob, which heeds solely the unifying promptitude of its feelings, conspicuously lacks the quality of mind. Pundita testifies, by the way, inconsistently. The barge incident gives evidence of a mob-like presence in 2848. Despite Pundita’s claim, then, the masses of the future “run directly contrary to the natural analogies.”

“The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” (1839), “The Colloquy of Monos and Una” (1841), “The Power of Words” (1845), and “Mesmeric Revelation” (1844) should be considered in close association to one another, not least because the first three make a noticeable sequence. “Mesmeric Revelation” for its part links the three Pseudo-Platonic dialogues to atomistic universe of Eureka. The dialogic sequence puts itself at odds with “Mellonta Tauta” in that “Eiros and Charmion” tells of the destruction of humanity; and “Monos and Una” suggests a date for that event about five centuries hence, thus cancelling the year 2848. “Eiros and Charmion” also invokes a realm of spirit, the setting again of “Monos and Una” and “The Power of Words,” that proves itself impervious to accidents of gross matter, and to which consciousness migrates when released from the body by death. “Mesmeric Revelation” purports to be an interview between “P,” a Mesmerist, and one Mr. Van Kirk, who, on the brink of death from a heart infection, seeks asylum in the hypnotic trance. He speaks from his reverie of occult lore. He lectures “P” about the gradations inherent to the cosmos that Poe will invoke four years later in Eureka and “Mellonta Tauta”: “There are gradations of matter of which man knows nothing”; and these “increase in rarity or fineness, until we arrive at a matter unparticled – without particles – indivisible – one.” This foreshadowing of quantum foam “is God,” and “what men attempt to embody in the word ‘thought,’ is this matter in motion.” Consciousness, for Poe, is continuous with matter but at the same time it transcends matter.

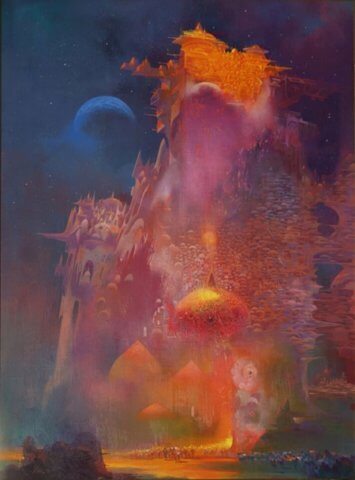

Joseph Mallord Turner (1775 – 1851) – Burning of the Houses of Parliament (1834)

PART TWO. The worldwide, instantaneous ekpyrosis of “Eiros and Charmion” illustrates Poe’s thesis dramatically. In “Eiros and Charmion” Poe wrote the first cosmic-collision story, to be followed fifty years later by H. G. Wells in “The Star,” and popular ever since. Cosmic-collision stories tend to be end-of-the-world stories, a pattern set by Poe’s dialogue. Earth passes through the tail of a large comet, the chemistry of which draws the nitrogen from the atmosphere, leaving only the oxygen, at which point everything combustible, including the human body, bursts into flame. Eiros, who died in the extinction-event, narrates the last moments of life to Charmion, who had graduated to “Aidenn” by ordinary death prior to the cataclysm: “For a moment there was a wild lurid light alone, visiting and penetrating all things”; then – “the whole incumbent mass of ether in which we existed, burst at once into a species of intense flame, for whose surpassing brilliancy and all-fervid heat even the angels in the high Heaven of pure knowledge have no name.” Eiros quotes the Apocalypse of St. John and remarks on the hauteur with which the humanity of the time dismisses the ancient lore of comets. In those passages subsists the criticism of wayward modernity: The mentality of the End-Times adhered only to “science” and rejected its connection to the cosmos – to God. Comets once signified, but they have become mere phenomena, “divested of the terrors of flame.” The awe that people once felt in respect of cosmic manifestations the final generation will need to re-learn in the moments before its demise.

Richard M. Powers (1921 – 1996) – Mountains of the Sun (1974)

The worldwide human combustion turns out to be more a shift to a higher realm, or what “Mesmeric Revelation” calls “metamorphosis,” than destruction. Another fitting word, initiation, names a quality that the future society, dedicated to an etiolated self and never-ending diversion, conspicuously lacks. Anthropology recognizes the importance of symbolic death in rituals of promotion; the initiand must always die in order to be reborn, that is, to proceed from a lower to a higher level. These same motifs pervade “Monos and Una” although Poe articulates his judgment of trends in the 1841 dialogue more explicitly than in the 1839 dialogue. The phrase mellonta tauta, which Poe extracts from Sophocles’ Antigone, serves for the epigraph of “Monos and Una” and thus glances ahead to the two items from 1848. Una plays the role assigned to Eiros in the previous installment of the dialogic sequence – the last of the two to die. Her question as she opens her eyes in Aidenn is, “Born again?” Monos affirms that Una is indeed born again and helps her to orient herself in the new-to-her environment of the unparticled ether. He remarks in addition that, “Unquestionably, it was in the Earth’s dotage that I died,” and logically then so too Una. The idea of “Earth’s dotage” accords itself with the social and cultural deformations of Poe’s fictional future, that decadence being the ultimate result of trends already in evidence in Poe’s own mid-Nineteenth Century.

Monos rehearses the crisis of his and Una’s time, more for the reader than for Una: “You will remember that one or two of the wise among our forefathers – wise in fact, although not in the world’s esteem – had ventured to doubt the propriety of the term ‘improvement,’ as applied to the progress of our civilization. There were periods in each of the five or six centuries immediately preceding our dissolution, when arose some vigorous intellect, boldly contending for those principles whose truth appears now, to our disenfranchised reason, so utterly obvious – principles which should have taught our race to submit to the guidance of the natural laws, rather than attempt their control.” Monos dismisses the “utilitarian” mentality as retrogradation, but he praises “the poetic intellect,” extolling it as the approach to reality “which we now feel to have been the most exalted of all.” Only the “poetic intellect” could achieve, by its investigative subtlety, “that analogy which speaks in proof tones to the imagination alone and to the unaided reason bears no weight.” The word analogy in “Monos and Una” looks forward to the word intuition in “Mellonta Tauta.” Intuition and analogy belong not to standard logic; that is to say, they belong not to the restrictions on thought imposed by the reigning pseudo-philosophical schools, Utilitarianism being exemplary. The earlier reference to “natural laws” defines a quality of depth in cosmic reality that “unaided reason” cannot reach and in which it arrogantly and volubly disbelieves.

Monos continues: “The great ‘movement’ – that was the cant term – went on… a diseased commotion, moral and physical. Art – the Arts – arose supreme, and, once enthroned, cast chains upon the intellect which had elevated them to power.” By “arts,” Poe means industry. He writes in Blakean images of “huge smoking cities… innumerable”; and of how “green leaves shrank before the hot breath of furnaces.” Humanity sickened itself with “system” and “abstraction.” Ignoring the hierarchic principle in the cosmic structure, “wild attempts at an omni-prevalent Democracy were made,” and “among other odd ideas, that of universal equality gained ground.” Contributing to the plague of cultural degeneration was “the perversion of our taste, or rather in the blind neglect of its culture in the schools.” Monos argues that “taste alone could have led us gently back to Beauty, to Nature, and to Life.” He ends his peroration by calling on “the pure contemplative spirit and the majestic intuition of Plato.” Presumably the conditions in Aidenn validate Plato’s insights. Ascending from Earth to Aidenn, one climbs out of the shadowy Cave and into the sunlight. Poe read Edmund Burke and draws some of his socio-political analysis from that source. Poe had probably not read Joseph de Maistre, but he echoes the Savoyard theorist nevertheless. What impresses the reader, however, is Poe’s forecast of those reactionary critics of the first half of the Twentieth Century such as René Guénon and Julius Evola, who might well have been familiar with his work.

Asher Durand (1796 – 1886) – God’s Judgment on Gog (1852)

In The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Time (1945), in the chapter on “The Postulates of Rationalism,” Guénon writes: “The moderns claim to exclude all ‘mystery’ from the world as they see it, in the name of science and a philosophy characterized as ‘rational,’ and it might well be said in addition that the more narrowly limited a conception becomes the more it is looked upon as strictly rational.” Guénon adds that, “Since the time of [the] encyclopaedists of the eighteenth century, the most fanatical deniers of all supra-sensible reality have been particularly fond of invoking ‘reason’ on all occasions, and of proclaiming themselves to be ‘rationalists.’” According to Guénon, the modern mentality restricts itself by denying the existence of the unobvious. By so doing, it deprives itself of the organ of theory, a designator which by its etymology suggests the apperceptual penetration beyond phenomenality into the deeper structures of cosmic reality. Guénon’s “mystery” names the cosmic liminality which makes itself available neither to direct sensory perception nor to logical deduction, but which language can capture in figure and story, as in Plato’s “true myths.” When Poe invokes “the poetic intellect,” he names the same thing. When Guénon condemns modernity as reducing everything to quantity, he reproduces Poe’s criticism of democracy and industrialism, both of which demote the human being from a person to a unit, whether in the voting mass or on the factory work-floor.

In Ride the Tiger (1961), in the chapter on “The Procedures of Modern Science,” Evola writes: “One of the principal justifications for Western civilization believing itself, since the nineteenth century, to be the civilization par excellence is natural science. Based on the myth of this science, preceding civilizations were judged to be obscurantist and infantile; prey to superstitions and to metaphysical and religious whims.” Evola adds that, “None of modern science has the slightest value as knowledge; rather, it bases itself on a formal renunciation of knowledge in the true sense.” For Evola as for Poe, knowledge implies a degree, at least, of participation. There is moreover in Evola’s view a ladder of knowledge that one ascends by initiation, as in Plato. Evola like Guénon wrote books on initiation, which he observed to be strikingly absent from the modern social fabric. Modernity replaces initiation with public education, so-called. Modernity indoctrinates rather than teaches; it actively suppresses curiosity and favors the inculcation of an impoverished mental conformity based wholly on denial of the transcendent. At the same time it stokes its own pride in its spiritual paltriness. Poe’s rapier-like satiric jibes in “Mellonta Tauta” demonstrate his irate opinion in respect of parochialism and abstraction in the modern outlook. Poe equates stupidity with a lack of taste and a failure to recognize beauty. “Taste alone” might have forestalled the decadence of the nations that both Monos and Una experienced in their earthly lives, where “taste” is the attunement to beauty. The homage to Plato in “Monos and Una” shows that Poe took seriously the philosopher’s claim that the search for wisdom is also the search for beauty – that it is the beauty of wisdom that exerts its erotic effect in drawing the spirit upward.

The third and shortest installment of Poe’s “Aidenn” sequence takes the name “The Power of Words,” and it gives to its colloquists the monikers of “Oinos” and “Agathos.” In this dialogue Poe brings his initiatic theme to the fore. He also attaches his psychic-atomist theory of the minded cosmos to tradition of the Logos-Philosophy, as the title might suggest. “Oinos,” the more recent death, awakes in the angelic domain with an utterance that attests a need for immediate instruction: “Pardon, Agathos, the weakness of a spirit new-fledged with immortality!” Oinos – who despite the name appears to have been female in her earthly sojourn – acknowledges herself as having assumed the role of initiand, with Agathos as her initiator. Oinos had expected that, translated to a post-mortem life, she “should be at once cognizant of all things, and thus at once be happy in being cognizant of all,” but Agathos corrects her. He says: “Ah, not in knowledge is happiness, but in the acquisition of knowledge! In forever knowing, we are forever blessed; but to know all were the curse of a fiend.” Not from knowledge, but from discovery as when Archimedes shouted “Eureka,” comes the boon of happiness, yet only fleetingly. The sustenance of happiness consists in a quest never completed. But what of the final clause? It points to the hubris of pretended knowledge and to the conceit of the modern mind, which thinks itself omniscient. The modern truncated mind well deserves the satanic epithet of “fiend.”

Paul Lehr (1930 – 1998) – Parapet in Golden Light (1975)

As Agathos leads Oinos “step by step” toward familiarity with her vita nuova, readers learn along with her. The universe, Agathos explains to Oinos, is a secondary creation. Oinos asks, “Do you mean to say that the Creator is not God?” Agathos responds how: “In the beginning only, he created.” In Eureka, Poe employs many times the phrase “the Volition of God,” which God imparted to the singularity in order to call forth the universe in the radial dispersion of the atoms. Thus, “The seeming creatures which are now, throughout the universe, so perpetually springing into being, can only be considered as the mediate or indirect, not as the direct or immediate results of the Divine creative power.” The date of “The Power of Words,” 1845, places it chronologically close enough to Eureka to make plausible that what obtains in the later text obtains in the earlier one. The reader may therefore presume that in “The Power of Words” the Divine Principle inheres in thought, just as it does in Eureka. In “The Power of Words” thought, itself, inherits the creative impulse of “the Volition of God.” Agathos leads Oinos through space to show her a newly born sun that leapt into being from the loving ardor of their earthly attraction. “This wild star,” says Agathos – “it is now three centuries since, with clasped hands, and with streaming eyes, at the feet of my beloved – I spoke it – with a few passionate sentences – into birth.” The proclamation of Agathos amalgamates Thought and Word, Nous and Logos, and lets the alloy of them permeate the cosmos as an underlying vital tissue.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God,” writes John in his Gospel. According to Poe, as he phrases it in the concluding paragraph of Eureka, everything in the universe possesses by its nature a suspicion of partaking in the universal vitality. The “Intelligences” that populate the cosmos are “conscious, first, of a proper identity,” and “conscious, secondly and by faint indeterminate glimpses, of an identity with the Divine Being of whom we speak – of an identity with God.” Not to enjoy this hunch requires the assumption of a prideful repudiating stance in regard to the sublimity of Creation. Modernity’s quintessence is to view the cosmos as a dead object to which it has nothing but a manipulative relation. Modernity holds this view in the mode of bad faith. It must constantly suppress the suggestions of order and meaning in phenomena while at the same time denying to itself that it undertakes such suppression. Modernity therefore consists, in part, of an attack against language – against the Logos. Poe’s usage of the word cant speaks to his awareness of modernity’s determination to evacuate language so as to make it purely instrumental, a tool for barking orders. In one syllable, cant assembles the anti-qualities of an age and a mentality drunk on themselves: The hypocrisy, sanctimony, pietism, covetousness, and vulgarity of a new, materialist Puritanism that thirsts after power. In his satirical “How to Write a Blackwoods Article” (1838), Poe notes that the meaning of cant has undergone a modern appropriation-reversal: “No profundity, no reading, no metaphysics – nothing which the learned call spirituality, and which the unlearned choose to stigmatize as cant.” That describes the linguistic environment of journalism in Poe’s day. Poe should get some of the credit that goes to George Orwell for his “Newspeak,” the principle of which Poe grasped one hundred years prior to the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

A Note on the Gallery. Joseph Mallord Turner (1775 – 1851) became increasingly interested in the last two decades of his life in light effects. Through Thomas Cole (1801 – 1848), Turner influenced the “Luminist” offshoot of the Hudson Valley School, as visible in the work of George Inness (1825 – 1894), Thomas Moran (1837- 1926), and Frederick Edwin Church (1826 – 1900). Turner, under the influence of Goethe’s color theory, explored in his oils-on-canvas and his watercolor sketches the character of light under diffusion and refraction in the atmosphere – most famously, perhaps, in his breakthrough painting Rain, Steam, and Speed (1840). The treatment of light in Turner’s work and in that of the Hudson Valley School shows a parallelism with Poe’s atomist cosmology. In a canvas like Turner’s Light and Color or Rockets and Blue Lights (both 1840), the painter equates the diffusion of the solar rays with the pervasion of spirit in a minded cosmos; the directionless bright glare resembles what Poe in Eureka describes as the unparticled matter, and which he identifies with mind, spirit, life, and God. A Similar effect appears, to name but one example, in the canvas Sunset in the Yosemite Valley (1868) by Alfred Bierstadt (1830 – 1902), where the sublimity of the immense palisades seems to draw in the light, as if by a living affinity. In her study of George Inness and the Visionary Landscape (2003), Adrienne Baxter Bell writes: “With little sign of an artistic presence, of a mortal architect originating and engineering the representation, we begin to attribute the Luminist’s fixation on order and structure, not to the artist’s own unique, potentially capricious temperament but rather to the implied presence of a more powerful organizing force operating above and through the artist, operating through and in concert with nature herself.”

Albert Bierstadt (1830 – 1902) – Sunset in the Yosemite Valley (1868)

The Hudson Valley School oriented itself to Ralph Waldo Emerson and Transcendentalism. Poe’s Eureka, however, is very much a response to Emerson’s Nature, written by a tougher and more acerbic mind than Emerson’s, to be sure, but not without continuity with the precursor text. It should be remembered, moreover, that Emerson too was in some ways a critic of modernity. In typical romantic fashion, he characterized the existing civilization as something of a dead weight and he remarked the uglification that went along with spread of industry. The great vital intellects belonged to the past; they had expressed themselves in figurative language incomprehensible to the contemporary, badly schooled mentality and they participated in the cosmos rather than standing back from it in hopes of manipulating phenomena for profit. Emerson held Plato in high esteem, as did Poe; and he drew on Immanuel Swedenborg, as did Poe. Poe therefore seems to be wrapped up in the spiritual art of the American school of painters as much as Emerson. Emerson and Poe both show traits of pantheism. The pervasion of light in the works of Cole, Inness, and Asher Durand (1796 – 1886) has a similar pantheistic implication. In Durand’s Judgment on Gog (1851), the jurisprudence comes not only from God the Orator, standing on the slab and looking out over the nation, but even more so from the manifestations of nature, including the light that He draws from the sky and fills with oracular birds. In Revelations, Gog is a reference to the satanic mob that will challenge the Reign of Christ. The Biblical Gog and Poe’s “Mob” in “Mellonta Tauta” are one in the same.

To illustrate Poe’s dialogue sequence – “Eiros and Charmion,” “Monos and Una,” and “The Power of Words,” I have selected one of Turner’s depictions of the great fire that consumed the Houses of Parliament in London in 1834 and a selection of Twentieth Century illustrations produced by artists associated with science fiction. (The invention of science fiction has, in fact, been attributed to Poe.) Richard M. Powers (1921 – 1998), in his semi-abstract Mountains of the Sun (1974), recreates the special optical effects of Turner’s study in a Twentieth-Century, science-fictional style. His painting could well have taken its inspiration from “Eiros and Charmion.” A kind of cosmic fire seems to be consuming a world. Power’s abstract figures provide a commentary on contemporary civilization: Man has become abstract through the pervasion of his own abstractions; he has become device-like and expressionless. Paul Lehr (1930 – 1998) also paints in a semi-abstract style although his images are more decipherable to the viewer than those of Powers. His Parapet in Golden Light (1975) strikes me as a glimpse into Poe’s “Aidenn,” the Spiritual Realm in which the dialogue sequence takes place. Something of Luminism inhabits Lehr’s forms: The light in the grand architecture seems organic, as if it were indeed spiritually sourced illumination. Both Powers and Lehr achieve a mythopoeic iconism in their illustrations of fantastic texts. In Poe, the loss of contact with mythopoeia weakens humanity in that it restricts the access to meaning in the cosmic structure. Science fiction, when it functions at its highest level, tends to be, not only mythopoeic, but also eschatological. There is no real tension in placing Durand and Lehr side by side (so to speak) as graphic material relevant to the exotic prose of E. A. Poe.