Reviving the Teaching Office: Moses, Paul, Wesley, and Reverend Wallace

You call me Teacher and Lord–and you are right, for that is what I am. So if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set an example, that you should do as I have done to you.

– John 13:13-15[1]

A Personal Introduction

The impetus for this essay arose out of our desire to understand our own unique educational predicament as it was related to the Christian ministry. The teaching and virtue of the Gospels came home to us; while moral virtue could be learned in the school, only the acquisition of enduring moral habits, obtained through one’s association with exemplars–teachers of Christian virtue by example–could be lasting. We realized at an early point in our ministry that our moral and spiritual reinvigoration came as the result of an effort to order our own soul. And the greatest sources of this spiritual renewal–the Church, the family, and moral exemplars–have continued to guide us after many years of ministry. These experiences provided the basis for our insuperable dedication to the rising generation.

Through the Incarnation we assume a position of dignity in a fallen world. God was able to take on human form only due to the fact that humankind is made in God’s image. The ability to choose between the higher and the lower potentialities of life, and the gift of critical reflection mark the central gifts of Christian life and are only possible, we believe, because of humankind’s likeness to God. As one progressed toward such an understanding, one could also be allowed to experience a Zetema, a period of significant self-illumination, that would allow one to accept the centrality of the Incarnation.

Even amidst the current crises in American Protestantism, we affirm that the Christian pastor must assume the role of teacher if the knowledge is to be transmitted. Lesslie Newbigin has described the process as intra-generational dialogue:

“The conversation between the present and the past must go on, and will go on, until the end of the world, and the perception of the first witnesses must have the premier role in the conversation.”[2]

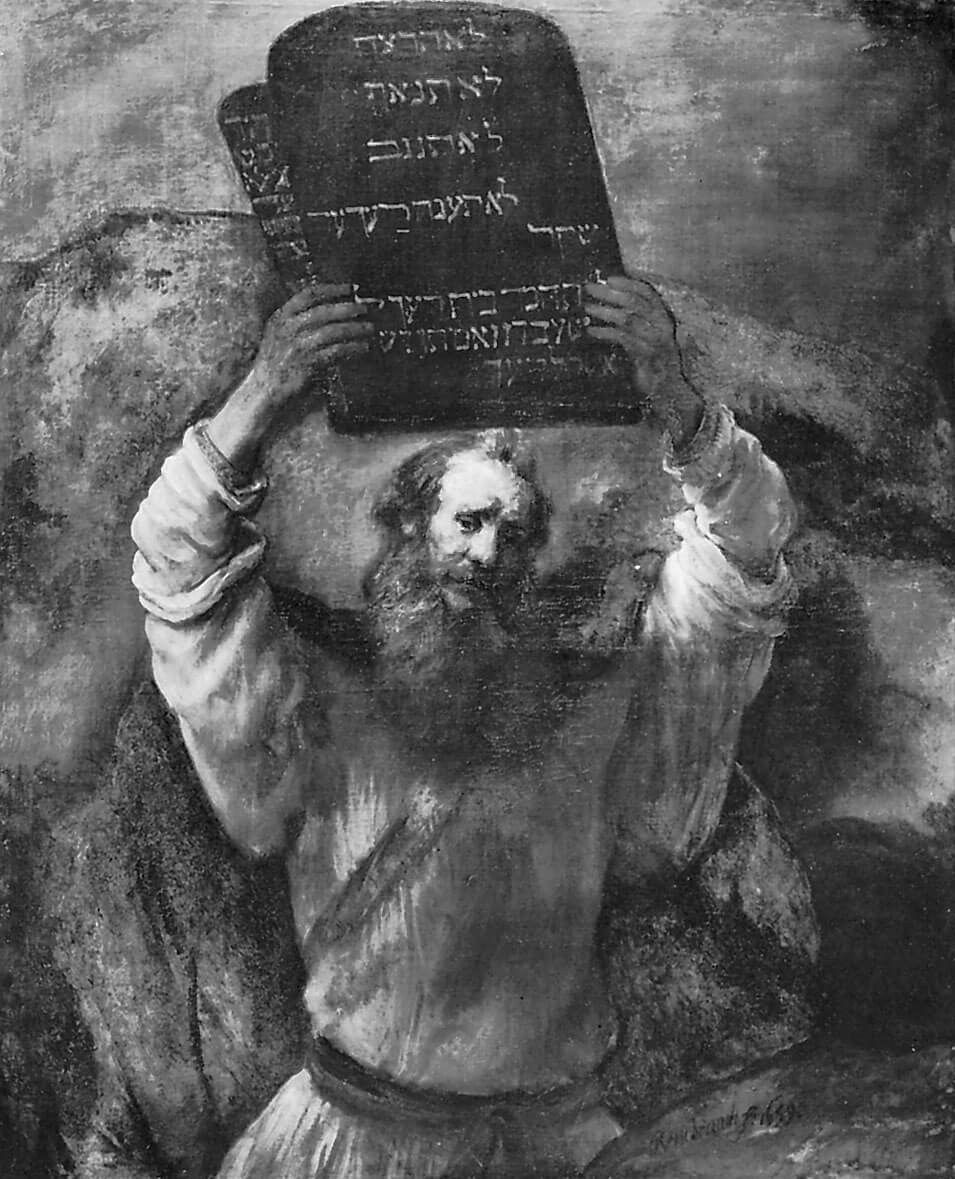

Throughout this essay we approach this problem of conversation from an historical vantage point, relying heavily on an overview of the contributions of three figures as models, as well as the underappreciated story of a contemporary practitioner of the teaching ministry. The first figure examined is Moses, the leader of the Hebrews. He, unlike any other leader of the Jews, possessed the unique theophanic experience that guided his teaching. Secondly, Paul the leader of the Early Church serves as an example of a man who while sharing the experience of direct revelation, was nevertheless required to present his “vision” to a new community of faith in turmoil and confronted with many limitations. The final exemplar to be encountered is John Wesley, the father of Methodism. Wesley, more than any other reformer with the possible exclusion of John Calvin, realized the importance of the teaching office and the education of laity clergy. The achievement of Wesley as an example for the contemporary church will be stressed.

The Hebrew Prophet as Teacher: Moses

Moses is a transitional figure, connecting the relatively compact world of Memphite theology to Christianity. This new differentiated field of experience is the most important break with the older order, but the role of Moses, as Eric Voegelin suggests, is even more epochal:

“The unique position of Moses has resisted classification by type concepts, as well as articulation through the symbols of the Biblical tradition. He moves in a peculiar empty space between the old Pharonic and the new collective sons of God, between the Egyptian empire and the Israelite theopolity. On the obscurities surrounding the position of Moses now falls a flood rather than a ray of light, if we recognize in him the man who, in the order of revelation, prefigured, but did not figurate himself, the Son of God.”[3]

This symbolization could be understood as an effort to “overcome” the compactness of the Egyptian order and the movement towards the more highly developed Christian period. Through Moses and the messianic symbolism attached to him, we have the beginning of the “divine order” that results in Jesus. Moses embodies the characteristics of the “Son of God,” although he is reluctant to accept the challenge of the charge. The “Son of God” is more than the figure of Moses, it must include the movement from Egypt, which Moses leads. Moses must also organize and guide a group of people who have refrained from making the necessary sacrifices and commitments for the sojourn out of Egypt. At one juncture his followers accuse Moses of attempting to kill them on the journey and ask him to return to Egypt.[4] Moses perseveres and regains his control of a skeptical lot. So we find in Moses, the teacher and seeker of order, the basis for a transformation of a clan of Hebrews into the divinely-inspired nation. Moses can undertake such a mission precisely because he experienced the theophanic reality, and Israel as the “Son of God” could have never existed had it not been for Moses.

As Voegelin notes: “There never would have been a first-born son of Yahweh if the God had had to rely on the people alone;…it had its origin in Moses.”[5] The creation of Israel is the experience of Moses’ “leap in being,” his extraordinary advancement in perception that he shares with the Israelites. This presence allowed the people of Israel to understand the human condition much more thoroughly than any previous civilization had been able to understand it; in this sense, Moses translates and fulfills the requirement placed upon him by the Divine that remains valid for Christian ministry-present God’s message accurately and as completely as one possible can to the people of God.[6] The demand on the disciple remains intact, regardless of circumstances. Our late professor, David Steinmetz, described Carl Michalson’s translation of this idea for a Christian cleric: “…preach the faith of the Church even if they could not claim the whole of that faith for themselves. The Church, he said, lives from the word of God; it cannot live from heresy.”[7]

The expatriation of the Israelites marks the decline of the Pharaonic order. Egypt is no longer the most favored empire and it must surrender its status in the world. Yahweh forces the Pharaoh to relinquish his title of the “Son of God” and it is assumed by Israel; therefore, it is no longer bestowed on a single individual. Egypt can never again exert the control it possessed in the past; the Pharaoh, in an effort to save his kingdom, appeals to Moses and Aaron to depart quickly and promises not to attempt to follow the emigres.[8] The post-exodus Egypt will not be the same as before, for now a greater power than the Pharaonic will have been recognized and it is Moses as teacher who presents this community and message to the world.

The new “Son of God” is a coherent social movement, but the group is again unable to provide the necessary leadership to make the departure from Egypt. It is at this point we notice a more differentiated symbolism making its appearance: the revelation to Moses in Exodus 2 and 3. In Exodus 2:15-25 the Pharaoh dies and people of Israel remain in bondage and continue to pray for deliverance. Moses has fled Egypt and is in the land of Midian. In Midian the God of the Fathers reveals himself and tells Moses he will serve as the leader for the removal of the people of Israel from Egypt. In verse 25 the condition of the people of Israel is acknowledged by God as a reaffirmation of the Mosaic call. Voegelin argues Yahweh was already a recognized deity, thereby affirming a procession of symbols that were in the process of change. Yahweh’s entrusting of the fate of Israel to Moses indicates the importance of the revelation. The procession of tension through Exodus 2 marks the awakening of Moses to his competition with the Egyptian regime. He has no alternative except to assume the mantel of leadership and suffer the consequences of his decision. The divinity expresses himself through his actions and these events are evidenced by the instances where we are told “God knew” of the situation of the Israelites. God is presented as always participating in human history and maintaining a desire to improve the lot of humanity, albeit he does not always take an active role in these activities.

The revelatory acts are the most prominent example of the continuation of the Berith that can be found in the Old Testament. The covenant is renewed and ratified by the thornbush experience of Exodus 3:14; the “mutual presence of God and Moses in the thornbush dialogue will then have expanded into the mutual presence of God and his people.”[9] A troublesome aspect of the encounter neglected by Voegelin is the manifestation of the divine to Moses–it is ehyeh, not Yahweh. When Moses returns to the Israelites, he tells his people “Ehyeh has sent me.” The patrimony of the Yahweh’s name is not a major concern of this paper, but it explains why one can be inconclusive about the different representations of the divine in the thornbush pericope. The most important consideration is the outburst, which indicates it is not an unintelligible act, but a remnant of the compactness of the older order. The hidden God in the thornbrush reveals the connection of God, through Moses, and the new constitution of being. The people and the divine can no longer be separated and their historical constitution is revived through this event.

Above all, a certain sense of balance prevails and the continuity advances our understanding of the figure of Moses as teacher. The new order is of the people of God and the revelatory act involving Moses is now shared with his people. Moses’ struggles are the struggles of the people of Israel.

Moses is not the historian of Deuteronomy, but he is a spiritual teacher. Most profoundly, Moses serves as the nabi, the man in whose heart and mind the “leap of being” occurs. He is no longer, Voegelin notes, a messenger of the Berith, but the medium for the message. Moses is the stimulus for the sign of the divine as he unites the order of the people in the present with the divine rhythm of existence. Humankind must continue to profess his devotion to the divine to preserve his relationship and through Moses the presentation of this reverence is permitted.

Moses as teacher shares a legislative quality as well.[10] He frequently presents decisions for the welfare his people and through personal persuasion demonstrates a propensity for solving disputes. Moses serves as an arbitrator, attempting to reconcile factors unwilling to settle quarrels within the people of Israel. Moses is depicted within the Old Testament as the recorder of memorable events, but not as the historian of his people.[11] He is also liberator. He brought his people out of a state of slavery into a condition of political freedom. Moses must be distinguished from the modern proponents of liberation theology who seek to expand the political and limit the role of the sacred in political life. Voegelin’s limited “liberator” is a reformer, although he possesses an element of restraint. He is also able to translate the transcendental tension in the life of the nation of Israel into a triumph in this world in the form of a kingdom in Canaan. Moses’s soul has been awakened to the pneumatic differentiation, and it is Moses the teacher and proclaimer who is able to discern the emerging transcendent element between the divine and the earthly realms.[12]

St. Paul and the Teacher in Early Christianity

The letters and ministry of Paul represent the most accessible account the Christian as teacher of the faith as it is related to the historical and spiritual tension in early Christianity. Nowhere are these tensions more obvious than in the Letter to the Romans. In the letter Paul addresses his flock in Rome in the following fashion: “To all God’s beloved in Rome, who are called to be saints: Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.”[13] The reader can understand Paul’s impetus for writing at this point, at least on a superficial level, as being motivated by his love for his fellow communicants. The letter, now canonized as the sixth book of the New Testament, is the longest letter written by Paul; it contains the most elaborate discussions of the Christian “life” to be found in the Pauline letters.[14] The letter to the Romans is, therefore, one of the most important documents of the Christian faith–it has been called “the theological epistle par excellence.”[15] While the study of this letter is essential to an understanding of the Christian logos, one cannot enter into such a study in a half-hearted way. This is especially true when one is attempting to exegete Paul’s view of Christian freedom, civil responsibility and divine revelation in accordance with the changing demands of early Christian society.[16]

As William Thompson has noted, the concentration on the theme of a vision as the uniting textual theme of Paul’s writings, and Romans in particular, would find much support among contemporary Pauline scholars.[17] Romans 12:1-15:13–the “obedience of faith” division, has been generally affirmed as a coherent separation.[18] Additional documentation for this view is provided by Origen and its importance is also stressed by other Church Fathers.[19]

The pedagogical legacy, or the ramifications of the Pauline vision as it is presented in his letters, is of great concern to the contemporary Christian. The explication of Paul’s vision is a Pandora’s box, full of potentially troublesome problems. Paul’s experience served as an opportunity for the revival of the Platonic spirit of an ordered cosmos, a defined reality encompassing the full spectrums of tensions, and including the divine and the earthly presented in its “classic form” throughout the Epistles (for example, Romans 8:18-25); in the aftermath of the great breakdown in Eden, the Pauline version of history commits man to a state dominated by a condition based on a feeling of the “senseless of existence.” The world is left waiting for the new force of redemption, the source of eternal salvation. This redemption will at least set our bodies free to enter a state of total freedom. The challenge for the Christian teacher is a double-edged sword–the prospects for a “distortion” are indeed great, but it is only through this unrealistic transformation that we can approach the deeper meaning of the event. Paul is proposing a view of man as a “relational self,” and his efforts and ministry are intensified by his personal relationship to God and his sense of mission. The ontological origins of this position are a defense of the self as part of a relational universe. William Thompson suggests that this relational self can be subdivided into horizontal and vertical dimensions.[20]

The Pauline “difference,” according to Thompson, is Paul’s stress on the fate of perishing. In the Pauline Letters one finds a serious break with the Platonic view of the existential order: the exodus of man is not separated from the removal of suffering in the world.[21] Man as a creature is changed by the experience of a singularly oriented consciousness. Paul, like John, perceives the Parousia as a “means to continue the event of divine presence in society and history.”[22] This Pauline preoccupation with the manifestation of the divine obscures Paul from coming to an adequate view of the world. Pauline knowledge is a greater awareness of the “pull,” the search for the metaxy as the quest for personal involvement in being, as the essential act of man’s intellectual faculty.

Paul presents himself as an impatient man.[23] Paul, in the barest sense, devoted his total self to the observation of the “divine irruption” in the life of the Christian community.[24] It is in this intense process that Paul’s differentiation of consciousness peaks, and he separates himself and his ministry even further from the classical tradition. Ultimately, the differentiation of these separate theophanies–with Paul’s disregard for the classical symbols, provides the ground for the break.

Paul’s message was to raise the reality of the Father and preach a message of righteousness. For Paul the “vision of the Resurrected” was more than a manifestation of the Divine, it was the reformulation of the absolute transcendent. And as a more practical concern, Paul is simply fulfilling the requirements of this by preaching and proclaiming a regime more strict than the law of the Jews. Paul was preaching a more austere and demanding message, while much of the old world was falling into disorder. This worldview does not have to be read as a gnostic or utopian exertion, it may have been the work of a man that was given a proclamation, the greatest ever pronounced, and recognized it demanded articulation. The teacher becomes a teaching church. David L. Bartlett has summarized the themes of this turgid and overly philosophical argument by stressing four functions of Paul’s teaching church[25]:

1) Tradition must be used to the Church’s advantage. As Bartlett suggests: “The fact that Jesus died and rose again does not change; the ways of appropriating those facts to our own faith may change.”[26]

2) The role of proclamation is central to the Pauline “plan” for a teaching ministry.

3) Exhortation as a guide to moral decision-making is an essential task of an Christian pastor.

4) Imitation as “practicing what one preaches” could serve as the most effective tool for the Christian minister. As we imitate Christ in the course of our lives, we come closer to becoming a more complete and accurate teacher.

The message of Paul can now also be articulated in a more practical sense. The importance of the pastor as the sharer, proclaimer, and witness of the good news allows the reader to comprehend to continuity of the post of pastor and teacher to the Church. Perhaps Robert Eno most aptly summarizes the movement involved in refining the teaching office in the early Church when he quotes Augustine’s basis for defending the Trinity and other sacred elements of the faith with a recapitulation of the Corinthian dictum: “We believe and so we speak.”[27] To understand the modern situation, we must turn to the man who is largely responsible for the modern revival of Christianity in the West, John Wesley.

Wesley, the Teaching Office, and the Methodist Educational Tradition

As Joseph Seaborn has argued, Wesley stressed the “the importance of as close a marriage as possible between faith and learning.”[28] Ted Campbell has detailed the relationship between Wesley’s affinity for the “manners of Ancient Christians” as a means of understanding and defending the Christian tradition.[29] For our purposes, we can authentically consider Wesley as part of an older, almost medieval tradition in religious life, who was forced to clarify his approaches to the education of clergy of the authority of the Church for an age dominated by a different, more discriminating temperament. Through his rearticulation of clerical holiness, Wesley is challenging the social contractarian view of religious life; he also raises the possibility that theological atomism could prevail if such a departure from normative ethos was implanted. Humankind for Wesley was a social and political being connected to community and if the connectiveness of the community was disrupted, the social order that had prevailed could falter. We are not examining an artifact in this section, but the work of a perspicacious student of life engaged in an effort to recover the lost soul of English evangelism amidst the temptations of the French Revolution.

For Wesley the question of teaching authority was essential for the preservation of the faith. In the course of his own life, he composed numerous works aimed at fulfilling such an purpose. Wesley’s Sermons, Sunday Service various letters are prominent reminders of this practice that appears to be neglected by contemporary Methodists. This “vital link” between the Church’s past and its authority as most readily examined through a conversational process; specifically, as Dennis M. Campbell demonstrates, the early conferences were to ask explain their courses of action through an examination of three fundamental questions:

- What to teach? (substance of the gospel)

- How to teach? (the proclamation of the gospel)

- What to do? (the gospel in action)[30]

Here, in sublime fashion, we a find the Mosaic, Pauline and Early Church understanding expressed for the modern mind. Wesley’s program was in an essential sense, a pragmatic program for church renewal. The organization of societies exhibited such concern. John Simon’s[31] early scholarship on Wesleyan societies suggests that Wesley believed a group should only be established if the members were willing to submit to the rigors of a disciplined course of study, demonstrating advancement in the Christian life that was “continuous and under constant watch.”[32] The leader of what became the “class meeting” served as a spiritual and personal mentor, and performed as the liaison between the communicants and the itinerant pastors.

The source of the teaching authority for the early Methodist movement was its communitarian connections; Thomas Langford has defined the relationship in this way:

“In John Wesley’s time, annual conference meetings served as the magisterium of the Methodist Church. This represented a conciliarist understanding, namely, theological judgments require the consensus of the community through its representatives. The role of Wesley was paramount…”[33]

The General Conference, of course, serves this function today. Langford proceeds to recount how the modern General Conference serves as the “interpretive authority” for the Methodist Church.[34] Bishops assist in this process by issuing doctrinal statements, although these offerings do not exert the same authority as General Conference decisions. The Methodist pastor can find solace in the fact the teaching office is explicitly presented in United Methodist Book of Discipline.

The quandary faced by the contemporary pastor cannot be the patrimony of his or her authority, which is affirmed by a strong confluence of notables, as we have attempted to demonstrate in this essay. The crux of the dilemma rests in the perceived lack of viable examples. Within the Methodism, for example, in the postwar period, one could present many paradigmatic expressions of the combination of clerical refinement and academic excellence that served to promote the cause of the Church universal in the modern world. In the remainder of this paper we shall encounter a figure who epitomizes the tradition of the theological rhetor, able to “rise above” the limitations and distractions of current debates, to see the critical concerns of his or her religious community and able to posit a message that is true to the requirements of the Gospels.

Reverend Jack D. Wallace, Jr.

While Moses, Paul, and Wesley provide an overwhelming spiritual and intellectual evidence of the need and vitality of the teaching office, we now turn to a contemporary example of a pastor-teacher who can also help guide the church and seekers of higher learning to understand and confront the modern world; however, his contribution has been ignored by contemporary pastors, scholars, and even his denominational authorities. The Reverend Jack D. Wallace, Jr., was deeply influenced by the scholarship of his theological and philosophical mentor, Thomas Oden. It was Oden’s attempt to renew the notion of humanism with the Wesleyan theological community that most interested the young pastor, who was deeply embroiled in the religious debates of the 1990s and 2000s. Wallace was attracted to the balance of sympathy and selection and recovery in Oden’s presentation and recognized the importance of the teaching office to the church at an early point in his ministry.[35]

As a person who personified the constant mission of a teaching ministry from his early years, Wallace was renowned as a reader and advocate for understanding the classic works of Christianity even as a young man. Growing up in Tyro, North Carolina, a small, unincorporated hamlet in Davidson County, Wallace’s studiousness and diligent defense of historical Christianity attracted the attention of various Methodist officials, and he was encouraged to continue his preparation for ministry at Pfeiffer University, where as the result of his scholarly labors, he excelled in sharing theological and devotional tomes with the large number of his fellow students, and drawing the attention of his religion professors as a person deeply committed to recovering the intellectual foundations of the Church. Wallace graduated from Pfeiffer University in 1990. He was ordained into the Methodist ministry after his graduation from the Divinity School of Duke University and served pastorates throughout Western North Carolina, including Walkertown and Lexington.

In the early elucidation of his endorsement of the teaching pastor, the centrality of Saint Paul and the Pauline texts was always pre-eminent. St. Paul, more than any other historical figure for Wallace, possessed the ability to see the significant matters in “right relations.” Paul, through his letters, presented the most accessible account of the historical and spiritual tension in the early Church. People of faith must be able to extract from human experience something more than an abstraction, Wallace argued, if these individuals can ever hope to receive the “full message” of the humanistic cause and the divine imperative.

The most mature and encompassing presentation of Wallace’s view of the teaching office was borrowed from Lynn Harold Hough’s The University of Experience and his The Christian Criticism of Life, seminal studies of the pastor as teacher that Wallace would purchase from used book stores and often share with fellow pastors and friends.[36] Wallace argued that a person’s view of the Middle Ages could tell you much about that person; if someone simply dismissed the period, Wallace believed, it was painfully obvious the person would be unable to appreciate the rich intellectual heritage available to the seeker of knowledge. The Middle Ages witnessed not just a renewed devotion to God, but a renewed attempt to appreciate the role of humankind in his relationship with the Divine. The work of Boethius, Saint Anselm, and especially Saint Aquinas, provided the proper synthesis of Christianity and the classical tradition. The basic contribution of the medieval writers was the inclusion of critical insight–and it is precisely in this addition that pastoral teaching, for Wallace, becomes a mature doctrine.

Through the incarnation, humankind is able to assume a position of dignity in a fallen world. God was able to take on human trappings only due to the fact that humankind is made in God’s image. The ability to choose between the higher and the lower potentialities of the Christian life, and the gift of critical reflection mark the central gifts of Christian pedagogy and are only possible, Reverend Wallace argued, because of humankind’s likeness to God. Social and spiritual well-being, as well as intellectual well-being, could be improved through the concept of Christian education. Improvements required the acknowledgement of a greater force in the universe than humanity. Well-being for Wallace was predicated on humankind’s happy and friendly acceptance of his or her position under God and over nature. The deeper understanding of God, the more he or she can understand that he is not divine; only God can serve as humankind’s Lord and moral exemplar.

During his life, Reverend Wallace’s views of faith and the Christian life were challenged, and his responses always and prophetically provide a groundwork for understanding the central issues of perpetuating both a knowledge of and devotion to a teaching ministry. For example, during his graduate studies at Duke University, Wallace, who served as a “late night” librarian at the Divinity School’s library, was approached by a scholar writing a defense of homosexual ordination. The scholar initially told Wallace that it was rumored that he was the best read of the evangelical seminarians, a claim Wallace denied, yet his notoriety as a bibliophile and his actual presence as a library employee suggested otherwise. The scholar proceeded to query Wallace about why he could not endorse homosexual marriage or the ordination of homosexual clergy. In Wallace’s response, he noted that Jesus and the Early Church was much more concerned about the poor, widows, and orphans, and these more vital concerns should guide one’s labors, and if studied, the tradition of Christianity concentrated upon these issues. The disappointed scholar soon departed from his encounter with Wallace. The scholar proceeded to express bewilderment to his colleagues, admitting that Wallace was so well acquainted with the Christian tradition and Holy Scripture he could not be distracted or diverted from his work or his diligent studies.

Reverend Wallace considered his idea of the Christian teacher compatible–albeit an extension of–the ancient tradition of Moses and Paul we have already critiqued. He turned his beliefs into positive action as pastor, teacher, and as a litteaur. In the life and witness of Reverend Wallace, we have a tremendous expression of the pastor and teacher who confronted a decadent society and discovered his oneness with God, and endeavored to share his insight with his brothers and sisters in Christ.

Even in the last years of his life, after a period where little support was provided for Wallace and his teaching ministry from those religious leaders called to oversee and support the ministry of Reverend Wallace, he was dismissed for his alleged failure to participate in church growth programs and similar ventures. Yet, to the end of his life, Wallace continued to preach and demonstrate how a teaching ministry could advance the Church. Eventually, without a pastoral appointment or empathic ecclesial oversight, Reverend Wallace found himself homeless, living in his car, but with a trunk and backseat filled with classic studies of Christianity that he would daily share with other homeless people he encountered, as well as the faithful members of Little River Methodist Church in Little River, South Carolina. During the last month of his life, he ardently organized a Bible study and reading groups for the people of faith he encountered, including a large contingent of homeless men that he lived among, taught, and served.

Conclusion

In the course of this essay we have considered three classical defenders of the spiritual leader as teacher, and a contemporary model that proves the teaching office can exist even in the most complex of situations. A critical position has been assumed in each case. These efforts have contributed to our understanding and are to be commended for their efforts to move beyond the normal parochialism that dominates this sort of discussion. All the works examined in this paper are attempts to reclaim the Bible and the teaching office as an appropriate subject for scholarly examination and participation.

References

Adams, James Luther. “Humanism and Creation.” Hound and the Horn, Volume 6, Number 1(October/December 1931), pp. 173-196.

Babbitt, Irving. Democracy and Leadership. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1979.

” . Literature and the American College. Washington, D.C.: National Humanities Institute, 1986.

Bartlett, David L. Paul’s Vision for the Teaching Church. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press, 1977.

Baldacchino, Joseph, editor. Educating for Virtue. Washington, D.C.: National Humanities Institute, 1988.

Bozeman, Jean. “Teaching in the Church: Privilege and Responsibility.” Currents in Theology and Mission, Volume 10, Number 5 (October 1983).

Campbell, Dennis M. The Yoke of Obedience. Nashville: Abington Press, 1989.

Campbell, Ted. John Wesley and Christian Antiquity. Nashville: Kingswood Books, 1991.

Cunningham, Floyd T. “Lynn Harold Hough and Evangelical Humanism.” The Drew Gateway, Volume 56, Number 1 (Fall 1985).

Dakin, Arthur Hazard. Paul Elmer More. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960.

Dulles, S.J., Avery. “The Magisterium in History: A Theological Perspective.” Theological Education, Volume 19, Number 2 (Spring 1983).

” . “Teaching Authority and the Pastoral Office.” Dialogue, Fall 1988.

Elliott, G. R. Humanism and Imagination. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1938.

Eno, Robert. Teaching Authority in the Early Church. Wilmington, Delaware: Michael Glazier, 1984.

Fox, Richard. Reinhold Niebuhr. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1985.

Grattan, C. Hartly, editor. The Critique of Humanism. New York: Brewer and Warren, 1930.

Hallowell, John H. The Moral Foundation of Democracy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1953.

Hoeveler, J. David. The New Humanism. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1977.

Hough, Lynn Harold. The Christian Criticism of Life. New York: Abington, 1941.

” Evangelical Humanism. New York: The Abington Press, 1925.

” “Introduction: The Dignity of Man.” The Nature of Man. New York: The Church Peace Union, 1950.

” The Meaning of Human Experience. New York: Abington-Cokesbury, 1945.

Hough, Lynn Harold. Personality and Science. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1930.

” The University of Experience. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1932.

Killian, Mary Vincent. Man in the New Humanism. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1938.

Langford, Thomas. Practical Divinity: Theology in the Wesleyan Tradition. Nashville: Abington, 1983.

Langford, Thomas. “The Teaching Office in the United Methodist Church.” Quarterly Review, Volume 10, Number 3 (Fall 1990).

Leander, Folke. Humanism and Naturalism. Goteborg: Elanders Boktryckeri Artiebolag, 1937.

Meeks, M. Douglass, Editor. What Should Methodists Teach? Nashville: Kingswood Books, 1991.

Prince, John. Wesley on Religious Education. New York: Methodist Book Concern, 1926.

Seaborn, Jr., Joseph William. “John Wesley’s Use of History as a Ministerial and Educational Tool.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Boston School of Theology, 1985.

Steinmetz, David. Memory and Mission. Nashville: Abington Press, 1988.

Williams, Robert. “Harold A. Bosley.” Twentieth-Century Shapers of American Religion (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), pp. 37-43.

Willimon, William H. and Robert L. Wilson. Rekindling the Flame. Nashville: Abingdon, 1987.

Notes

[1] Holy Bible: The New Revised Standard Version. Nashville: Cokesbury, 1990, pp. 107-108.

[2] Lesslie Newbigin, Truth to Tell: The Gospel as Public Truth (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1991), p. 9. See Geoffrey Wainwright’s Lesslie Newbigin: A Theological Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[3] Eric Voegelin, Israel and Revelation (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1956), p. 398.

[4] Exodus 14:11-12.

[5] Voegelin, Israel and Revelation, p. 392.

[6] We are indebted to the Russell Kirk’s description of Voegelin’s Moses in his Roots of American Order (Pepperdine: Pepperdine University Press, 1977), for much of this insight.

[7] David Steinmetz, “The Protestant Minister and the Teaching Office of the Church,” Memory and Mission (Nashville: Abington, 1988), p. 77.

[8] Exodus 12.

[9] Voegelin, Israel and Revolution, p. 407.

[10] We are clearly adopting the approach of Aaron Wildavsky at this juncture (Moses as Political Leader [Jerusalem: Shalem Press, 2005]).

[11] For Voegelin, Moses is more than the prophet one encounters in Biblical scholarship; he is a significant participant in the world around him and has much influence on that environment. See Israel and Revelation, p. 388-389.

[12] Eugene Webb’s “Eric Voegelin’s Theory of Revelation,” The Thomist 42 (1978) expands upon the brief assessment presented here.

[13] “Romans 1:7,” The New Oxford Annotated Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 1361.

[14] Matthew Black, Romans (Greenwood: Attic Press, 1971), p. 14.

[15] Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (Nashville: Abington Press, 1982), p. 112.

[16] For a more complete discussion of the problems one must encounter in this regard see Clinton Morrison, The Powers That Be (London: SCM Press, 1960), p. 11.

[17] See William Thompson, “Voegelin on Jesus Christ,” Voegelin and the Theologian (New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1983), p. 192.

[18] Robert Spivey and D. Moody Smith, Anatomy of the New Testament (New York: MacMillian Publishing Company, 1982), p. 388.

[19] W. G. Kummel, Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: Abington Press, 1975), p. 388.

[20] William Thompson, Jesus and Savior (New York: Paulist Press, 1980), p. 169.

[21] Ibid., p. 241.

[22] Eric Voegelin, “The Gospel and Culture,” Jesus and Man’s Hope, ed. D. G. Miller and D. Y. Hadidan (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, 1971), p. 78.

[23] Ibid., p. 78.

[24] The term “irruption” appears in William Thompson’s essay.

[25] David Bartlett, Paul’s Vision for the Teaching Church (Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press, 1977), pp. 74-77.

[26] Ibid., p. 75.

[27] Robert Eno, Teaching Authority in the Early Church (Wilmington, Delaware: Michael Glazer, 1984), p. 129.

[28] Joseph Seaborn, “John Wesley’s Use of History as a Ministerial and Educational Tool,” Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Boston University School of Theology, 1985, p. 237.

[29] Ted Campbell, John Wesley and Christian Antiquity (Nashville: Kingswood Books, 1991), p. 57. Chapter 4 of this tome is devoted to such an examination.

[30] Dennis M. Campbell, The Yoke of Obedience (Nashville: Abington, 1989), p. 104-106.

[31] John Simon, John Wesley and Religious Societies (Epworth: London, 1921), p. 212.

[32] We are borrowing from John W. Prince’s explanation of the situation [John Prince, Wesley on Religious Education (New York: Methodist Book Concern, 1926), p. 77].

[33] Thomas Langford, “The Teaching Office in the United Methodist Church,” Quarterly Review, Volume 10, Number 3 (Fall 1990), p. 5.

[34] Ibid.

[35] See Thomas Oden’s magisterial John Wesley’s Teachings (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013).

[36] Lynn Harold Hough, The Christian Criticism of Life (New York: Abington-Cokesbury, 1941).