Robert E. Howard’s Conan: A Paracletic Hero?

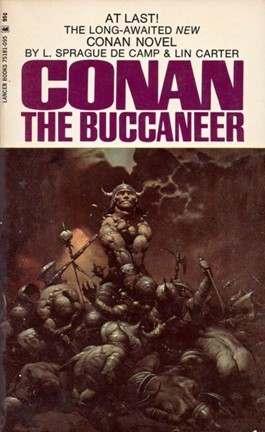

Robert E. Howard (1906 – 1936) faded rapidly into obscurity after his self-inflicted demise in 1936 following the death of his mother from tuberculosis. Ironically, Howard’s reputation had increased steadily in the lustrum preceding his suicide. Farnsworth Wright, the editor of Weird Tales, remained as parsimonious as ever, but other publications were clamoring for Howard’s work, which had branched out from weird fiction and barbarian stories into westerns, boxing yarns, and “spicy” tales. In the last year of Howard’s truncated life, he made a respectable living by writing and the prospect going forward looked good. The drop-off in his literary notoriety stemmed from the fact that, his work having disappeared from the pages of the pulps, and having never made it into book form, no persistent token presented itself that would remind the readership of his existence. Imitators filled the vacuum left by his disappearance although his literary executor, Otis Adelbert Kline, managed to place a few stray manuscripts posthumously. In 1946, August Derleth’s Arkham House issued an anthology of Howard’s short fiction, Skull Face and Others, but in a small edition aimed at aficionados. Howard’s popularity would revive only with the paperback explosion of the 1960s, helped by Frank Frazetta’s cover illustrations, but even then many of the stories that entered into print were extenuations of outlines and incomplete drafts undertaken by L. Sprague de Camp, Lin Carter, and others. It would take thirty, forty, or even fifty years for something resembling an authentic version of Howard’s authorship to come on the market and for his copious correspondence with Derleth and H. P. Lovecraft to make its way into the catalogues. Hollywood’s contribution in the form of Arnold Schwarzenegger as Howard’s most notable character, Conan the Barbarian, in 1982 and 1984, exploited Howard’s name but did nothing to represent his achievement. Vincent D’Onofrio’s biopic, The Whole Wide World (1996), based on Novalyne Price’s memoir of her relationship with Howard, by contrast, told the Conan-author’s story with genuine pathos, but enjoyed only a limited release.

Considering that he died at thirty, Howard’s literary accomplishments can only impress. Stylistically, he operates at a level many ranks above that of the typical pulp writer. His vocabulary includes a rich lode of Latin and Greek derivations and likewise of English archaisms. Brought up, from age thirteen, in the small and isolated Texas town of Cross Plains, in Callahan County, in the middle of the state, Howard almost miraculously overcame a lack of educational resources and acquired a reserve of knowledge in history, literature, myth, and folklore that would shame the modern holder of a college degree in any of those subjects. The story circulates in the biographies that Howard, as a teenager, would break into school and town libraries at night, make off with the books, and return them in the usual way once he assimilated their contents. Howard’s syntax follows varied patterns from short expostulations to sentences of many logically arranged clauses. His paragraphs likewise arrange themselves according to different models, from the short description of violent action, to lapidary descriptions of landscape and architecture and subtle representations of a subject’s mood and thought. Take a paragraph – chosen more or less at random – from Howard’s Conan story “Iron Shadows in the Moon,” which appeared in Weird Tales for April 1934 as “Shadows in the Moonlight.” Howard sets the story early in Conan’s career, before he rises to the kingship of Aquilonia, during the time when he rode as a hetman of the mercenary kozaks. The action takes place on an island where Conan and a young woman, Olivia, hide from their pursuers, the piratical Hyrkanians. At one point, Olivia and Conan enter the ruins of a great temple or palace whose contents include a gallery of remarkable statues. Howard writes –

Olivia glanced timidly about the great silent hall. Only the ivy-grown stones, the tendril-clasped pillars, with dark figures brooding between them, met her gaze. She shifted uneasily and wished to be gone, but the images held a strange fascination for her companion. He examined them in detail, and barbarian-like, tried to break off their limbs. But their material resisted his best efforts. He could neither disfigure nor dislodge from its niche a single image. At last he desisted, swearing in his wonder.

Of the seven sentences comprising the paragraph not one relies on a passive construction. Howard activates his verbs. The adverbs timidly and uneasily in the first and third sentences emphasize the girl’s alienation and nervousness. When the objects of her survey meet her gaze, the active verb hints at their actively supernatural quality, the topic of which Howard has already broached. In the second clause of the third sentence the phrase strange fascination underscores Conan’s keen curiosity and his sharp senses, always alert to danger, but possessing a deductive or inferential quality that signals the possessor’s intelligence. The ascription barbarian-like that Howard applies to Conan takes a detour through Olivia’s perspective. A subplot of the tale concerns Olivia’s revaluation of the terms barbarian and civilized. Her father has cynically and brutally betrayed her, selling her to a marauding prince who wants her only as a sex slave in exchange for a truce on the border; the prince then gave her away to another for a similar reason. Hitherto, Olivia has thought of her milieu as an instance of civilization, a concept that events have forced her to call into question. In her suppliant condition, Conan, whom Olivia first apprehends only as a Cimmerian savage, has extended protection at risk to his own life and has refrained from laying a hand on her although he remarks her youth and beauty. Conan’s testing of the statues, as the astute reader of Howard will have discerned, belongs to his grasp of magic based on his many experiences of its camouflaged deadliness and his habit of thoroughly examining every situation in which a threat might present itself. When Conan swears in the seventh sentence, he expostulates not because the sculptures have resisted his vandalism, but because an examination has yielded a disturbing conclusion. The sixth sentence displaces its subject; its two verbs, to disfigure and to dislodge, qualify as learned. Also learned are the phrases ivy-grown and tendril-clasped in the second sentence. All seven sentences announce a noticeable prosodic talent. The phrase great silent hall, which brings the first sentence to a close, forms a rhythmic cadence.

Howard wrote according to formulas – for the sound economic reason that he wanted to sell his yarns – but his writing frequently transcends formula. The “Shadows” story instantiates the phenomenon. In a typical “pulp” story of the sword-and-sandals variety, Olivia, for example, would function in a purely ornamental way. As Howard fashions her, she is in the story’s context an ornament, a dainty morsel intended for commercial trafficking on a monarcho-military game board. When she first appears, she qualifies less as a damsel in distress (albeit distress impinges) than as a frightened but conceited adolescent whose cruelly altered circumstances she cannot deny but has not yet fully comprehended. Olivia has, to her credit, escaped her captor, Shah Amurath, but he has caught up with her. When she bemoans her probable fate, Amurath says sadistically, “I find pleasure in your whimperings, your pleas, tears, and writhings.” He calls her “slut.” Howard now ushers Conan onstage. He also flees, in a manner of speaking, from Shah Amurath, whose army has ambushed and slaughtered the kozaks, with no quarter given, thereby flouting the rules of battle. In the ensuing contest of blades, Conan severs Amurath’s sword-arm at the shoulder. Amurath begs quarter, but, reminding him of recent events, Conan delivers the coup de grace. Olivia asks Conan for protection even though, as she says to him, “I fear you,” but she “fear[s] the Hyrkanians more.” Commandeering a skiff Conan rows them away to seek refuge elsewhere in the archipelago of Vilayet. Without explicitly agreeing, Conan has assented to Olivia’s request. He treats her as fragile, but admires the pluck of her escape. Without her intercessor, Olivia confesses, “I should be lost to all shame.” They come to the haunted island, with its weird ruins and other disquieting mysteries.

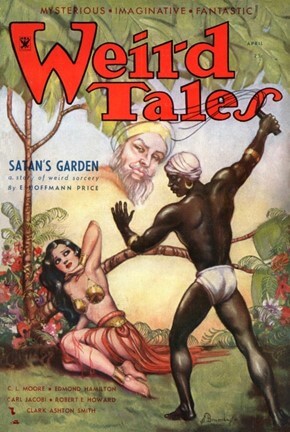

Howard’s story appears in the same number of Weird Tales as C. L. Moore’s “Black Thirst,” one of her Northwest Smith sagas, and Clark Ashton Smith’s “Death of Malygris,” an item in his Poseidonia cycle. Howard resembles Moore and Smith in achieving a signature literary style that betokens a profound literary basis, especially in the traditions of myth and epic, and an intuitive grasp not only of metaphysics, that science of the invisible, but of the deep structure of morality. Twenty years ago, in an article for the journal Anthropoetics entitled Monstrous Theologies, an obscure scholar of genre fiction classified Moore’s Northwest Smith as a “Paracletic Hero.” The author had discerned in reading Moore’s story-cycle the recurrent pattern wherein Smith acts to free an afflicted community from the tyranny of a sacrificial order. The term Paracletic derives from the Greek name for the Third Person of the Trinity, who functions, in one of his roles, to bear witness against the injustice of scapegoating, a human propensity that manifests itself as ritual – the immemorial but hidden reign of which Christian revelation brings to light. Smith’s stories likewise expose the gruesome vanity of sacrifice, but without the explicit moral framework of the Moore’s narrative and lacking a heroic protagonist. Sacrifice furnishes a recurring theme in the Conan sequence to the degree that Conan also qualifies, if not quite so fully as Northwest Smith, as a Paracletic Hero. Human sacrifice inspires Conan with revulsion. Conan’s deity, Mitra, whom he regularly invokes, figures in a religion that explicitly rejects human sacrifice and in so doing differentiates itself from the other cults of Howard’s Hyborian Age.

Howard wrote an essay on the Hyborian Age, which falls between the sinking of Atlantis and the rise of the historical civilizations. Howard tells how a Nemedian priest named Arus brought the religion of Mitra to the barbarians of the Northlands “to modify the rude ways of the heathen by the introduction of the gentle worship of Mitra.” The life ways of the heathen up to that point “were bloodthirsty.” When Arus expounded the morality of Mitra to the tribal chieftain Gorm, he “set himself to work to eliminate the more unpleasant phases of Pictish life – such as human sacrifice, blood–feud, and the burning alive of captives.” Howard draws a picture of Arus proselytizing Gorm concerning “the eternal rights and justices which were the truths of Mitra,” while “point[ing] with repugnance at the rows of skulls which adorned the walls of the hut.” Arus “urged Gorm to forgive his enemies instead of putting their bleached remains to such use.” Gorm, an intelligent man, converted. The Picts disseminated the teachings of Mitra to the neighboring tribes, including the Cimmerians. In the story “Xuthal of the Dusk” (Weird Tales for September 1933), Conan tells Thalia, a devotee of the sacrificial god Thog, “The Hyborians do not sacrifice humans to their god, Mitra, and as for my people – by Crom, I’d like to see a priest try to drag a Cimmerian to the altar!” He adds, “There’d be blood spilt, but not as the priest intended.” In “Xuthal,” Conan extends his protection to a youthful female named Natala whose life and honor a wicked society threatens. Crom is actually an old Irish deity, associated with war but also with honor and thus a twin of Mitra. The name Mitra belongs to the onomastic pattern of the Conan sequence. Howard uses Latin-, Greek-, Arabic-, and Germanic-derived names for people, places, and gods.

Mitra stems obviously from Mithra, the Persian deity whose cult enjoyed popularity among the Roman legions in the Second and Third Centuries, but it also takes its place in the primordial Indo-European trinity of Indra, Mitra, and Varuna. Beyond the non-sacrificial specification, Howard elaborates not on the details of the Cimmerian Mitra cult. It would not exceed possibility, however, that Howard had read, or least skimmed, Franz Cumont’s classic study, The Mysteries of Mithra (1903), which already in the 1920s existed in an English translation. A number of Cumont’s characterizations of Mithraic ethics apply to Conan, whether by influence or coincidence. In his chapter on “The Doctrine of the Mithraic Mysteries,” for example, Cumont writes that, “Resistance to sensuality was one of the aspects of the combat with the principle of evil.” He adds that, “To support untiringly this combat with the followers of Ahriman, who, under multiple forms, disputed with the gods the empire of the world, was the duty of the servitors of Mithra.” In survival mode or on the battlefield, Conan never succumbs to sensual distraction. He enjoys wine and women in his hours of leave, but in these things too he exercises discipline. Another sentence from Cumont aptly measures both Conan and the Mitra cult. The followers of Mithra, Cumont writes, “did not lose themselves… in contemplative mysticism”; but “for them, the good dwelt in action.” Conan directs his violence toward what might well be called “the principle of evil,” and he acts, broadly speaking, for the good. In his universal iconography Mithra famously battles and defeats a rampaging bull using a dagger. In “Shadows” Conan battles and defeats a rampaging ape, also using a dagger.

The Paracletic element in “Shadows” emerges in a vivid nightmare that Olivia experiences while she sleeps under Conan’s watch in the ruined temple that they earlier explored. In Howard’s words, “Olivia dreamed, and through her dreams crawled a suggestion of lurking evil, like a black serpent writhing through flower gardens.” The dream begins in “exotic shards of a broken, unknown pattern,” but soon yields to “a scene of horror and madness, etched against a background of cyclopean stones and pillars.” The architectural detail indicates that Olivia sees the ruined temple in its heyday. A group of “black-skinned, hawk-faced warriors,” who “were not negroes,” crowd the space. “Neither they nor their garments nor weapons resembled anything of the world the dreamer knew,” Howard writes. A lynch-mob-type many-against-one scenario obtains. The throng encircles “one bound to a pillar – a slender white-skinned youth, with a cluster of golden curls around his alabaster brow,” whose “beauty was not altogether human,” but “like the dream of a god, chiseled out of living marble.” The persecutors jeer and taunt their victim “in a strange tongue” while “the lithe naked form writhed beneath their cruel hands.” The victim cries out in pain. The sacrificers slit his throat. He slumps dead. What does the cumulus of details thus far mean? Howard has framed the story within Olivia’s re-evaluation of the opposite terms civilization and barbarism. The ruined temple might offer itself as an artifact of civilization. Its purpose, however, as the theater of bloody tributes to an unnamed but horrific deity, contravenes the truth of a civilized order. That a society might boast technical advances, such as the perfection of monumental architecture, never qualifies it as civilized. Being shackled to a pillar, meanwhile, resembles crucifixion. In “A Witch Shall Be Born” (Weird Tales for December 1934), Conan undergoes crucifixion. Yet the link between Conan and the victim although undeniable remains a bit vague.

The nightmare continues. In supernatural response to the brutal sacrifice of the white-skinned youth there came “a rolling of thunder as of celestial chariot-wheels,” whereupon “a figure stood before the slayers, as if materialized out of empty air.” Is it Mitra? The figure takes the “form” of a “man.” Nevertheless, “no mortal man ever wore such an aspect of inhuman beauty.” Furthermore, “there was an unmistakable resemblance between him and the youth who drooped lifeless in his chains”; despite this, however, “the alloy of humanity that softened the godliness of the youth was lacking in the features of the stranger, awful and immobile in their beauty.” Readers can only assume a paternal-filial relation of the awesome interloper and the slain ephebe. The deific presence lifts a hand and speaks. He utters the alien phrase, “Yagkoolan yok tha, xuthalla.” The blacks fall back, affrighted; they retreat “until they were ranged along the walls in regular lines,” just like the statues of inky adamant in the ancient fane. Olivia and Conan have heard the strange utterance before. When they first landed on the island, they disturbed a bird that ululated the syllables as it started away. The pronouncement takes effect magically: The offenders “stiffened and froze”; and “over their limbs crept a curious rigidity, an unnatural petrification.” The Intercessor now releases the victim from his chains and “he lift[s] the corpse in his arms.” He scowls at the frozen sacrificers and points to the moon. Olivia awakes in panic. She runs blindly, screaming. Her spasm of fear diminishes not until she sees “Conan’s face, a mask of bewilderment in the moonlight.” In their tense dialogue, Olivia tells Conan that the youthful victim was “as like as son to father.” What further meaning can be extracted from these additional details?

In their long chapter on the Conan sequence in Robert E. Howard: A Closer Look (revised edition, 2020) Charles Hoffman and Marc Cerasini strangely omit any reference to “Shadows.” In their commentary on “A Witch Shall Be Born,” they yet address the Texan’s attitude to religion generally and to Christianity particularly. They note that when Conan escapes from his cross a lust for revenge overwhelms his previous desire, while still nailed to the crossbeams, to “turn his back forever on the crooked streets and walled lairs where men plotted to betray humanity.” Instead, he works retribution on his tormenters, but in the process, as Hoffman and Cerasini cannot help but note, he liberates a city where the same men who persecuted him have imposed a murderous tyranny over the locals. The co-authors draw a dubious conclusion: “Christ died on the cross and Conan did not because one is a lamb and the other a lion.” Therefore, Conan can have nothing in common with Christ; he cannot be, as the present essay argues, a Paracletic hero. The trouble is that Conan repeatedly frees people from the sacrificial dispensation, as he does in “Shadows.” This makes the parallelism between Olivia’s oneiric vision and the Passion doubly poignant. The similarity even permits speculation about the nonsense syllables that the father-figure speaks. They condemn sacrifice as profanation. The clue lies in the concluding word, xuthalla, which echoes the Lovecraftian name of Cthulhu, whose appearance in “The Call of Cthulhu” (Weird Tales for February 1928) provokes a worldwide outburst of the primitive sacred including, in the chapter entitled “The Tale of Inspector Legrasse,” human sacrifice. As noted, Olivia and Conan first hear the phrase when a bird bleats it out. Birds belong to the iconography of the Paraclete.

There is more. Hyrkanian pirates land on the island. Conan encounters their captain, who immediately draws his sword. Conan defeats him. Bearing in mind the laws of the freebooters, Conan makes himself known to the dead captain’s crew, some of whom seem willing under custom to acknowledge him as their new leader-in-chief. As they lower their blades a betrayer slings a stone at the Cimmerian that knocks him out. The treacherous part of the crew wants to slay the unconscious warrior immediately, but he has enough defenders to postpone the deed. The buccaneers drag Conan, bound, to the ruined temple, where they undertake their usual practice and drink themselves unconscious. Olivia observes all of this from the hiding place on a cliff top where Conan has bidden her to remain. Olivia has two fearsome worries, that the pirates on awakening from their stupor will murder Conan and that the statues will spring to life under the magic of the moonlight and will murder everyone. The shackled Conan reminds Olivia of the pathetic victim in her cauchemar du sacrifice. Conan has saved her; she now decides to overcome her fear, a mighty struggle, and save Conan. If Conan in his straits resembled the son, Olivia in her resolution would resemble the father. She releases Conan from his bonds. While they flee the ruins, the statues come to life. As Olivia and Conan make their way to the pirate galley – the monstrous ape attacks them. Conan prevails. The remnant of the pirate crew shows up, at least half of them having been killed by the statue-men. They now readily submit to a new captaincy. As the ship unfurls its sails and heads into the main, Conan promises Olivia that he will make her “Queen of the Blue Sea.” The triumphant final act of “Shadows” corresponds truly to the pulp formula for adventure-heroism. The bizarre dream with its motif of redemption from a collective murder stands out in its anomaly. Howard redoubles that anomaly by his total insouciance regarding an explanation. Whether incidental or a conscious gesture of storytelling, the lack of an explanation makes “Shadows” both memorable and challenging, as if Howard had signed off with a “figure it out for yourself.”

Howard’s Hyborian Age is a pre-Christian phase of semi-fictive chronology, so that no one in a Conan story can be nominally a Christian. Scattered remarks in Howard’s Conan stories and those in his essay on the Hyborian Age make it clear that Conan adheres to what is probably a minority conviction in his world – what one could call the anti-sacrificial ethos that anticipates later developments in religion that go misunderstood even today, two thousand years after the Passion. Man approaches God – man honors the image of God that is in him – when he abjures the immemorial custom of sacrificing a victim. The impulse to sacrifice a victim acts like a hard-wired instinct. It belongs to the lower nature that man must overcome in order to honor his higher nature. The Mitra cult and Conan’s frequent invocations of the name Mitra constitute a salient feature, not a mere incidental or decorative one, in Howard’s Conan sequence. Another Conan story, “The Tower of the Elephant” (Weird Tales for March 1933), which traces an incident in Conan’s thieving youth, links itself by prolepsis to events in “Shadows.” The young Conan, seeking to steal an immensely valuable and extravagantly protected object, finds himself in the depths of a tower where an alien being has been trapped by the sorcery of an evil wizard for thousands of years. Conan and the being communicate. Their exchange of words evokes in Conan an overwhelming sympathy for the plight of the victim: “He stood aghast at the ruined deformities which his reason told him had once been limbs as comely as his own”; then “all fear and repulsion went from him, to be replaced by great pity.” Conan identifies with the victim; he likens the being to himself. Conan goes out of his way to liberate the being from the torment of paralysis and captivity, even to the extent of forfeiting his prize.

A friend and correspondent, one M.P., likes to say that Howard’s Conan is the greatest literary creation of the Twentieth Century. M.P. knows the great books backwards and forwards. He mistakes not Howard for Thomas Mann or Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He yet understands that Howard intuitively carried forth the ancient Indo-European tradition of epos – the hero-tale that also serves as a guide to male initiation in the lore of dimensions higher than those of civilized routines with their effeminate fastidiousness. Some tasks permit themselves only to be undertaken messily. Feminist English professors cannot undertake them. Most probably, feminist English professors do not even know that such tasks exist, that their consequences will overwhelm the order of things unless someone bold takes them up at risk to his life. The hero-tale indeed serves as a guide to the order of things, the origin and bases of which the conceit of modernity has put away beyond memory. A kind of Platonic anamnesis, or “unforgetting,” undergirds Howard’s Conan sequence, framed as it is in the vision of the Hyborian Age. The fiction of the Hyborian Age adds up to what Plato would have called a true myth. Howard’s phase before history hails the present in dreams to be remembered. It must be resurrected from the prevalent amnesia to make good a lack in the character of modernity. Every astute adult knows what a feminist English professor would say about Robert E. Howard and his creation, Conan the Barbarian. Early Twentieth-Century genre fiction – pulp fiction – foresaw the effeminacy of cultural changes coming down the pike. The genius of a Robert E. Howard, a Catherine L. Moore, or even of a Clark Ashton Smith, was to intuit that the feminization of Western culture would suspend the anti-sacrificial bias of the Christian dispensation, opening the way for the “cancel-culture” that bestrides us in 2021.