Social Hierarchies and Subtle Sabotage: Jane Austen’s “Mean Girls”

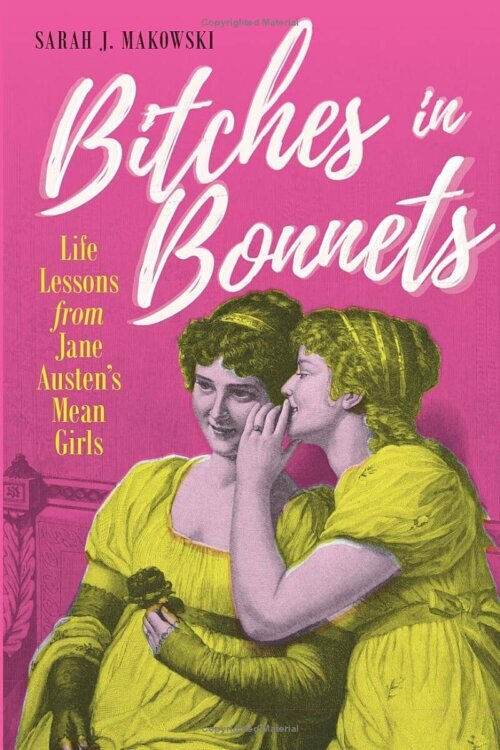

Bitches in Bonnets is a stunning and irreverent tribute to a fine pairing: women and Jane Austen. In this personal and sociological piece of literary criticism, Makowski investigates how female aggression affects “the lives of Austen’s female characters and her overwhelmingly female audience.” She says this comparison reveals, “things haven’t changed that much for women in this world” but “[i]t is up to every one of us to do our part to change things.” She surveys Jane Austen’s mean girls, provides insight into their (and our own) behavior, and attempts to offer solutions to the problem of female aggression.

Makowski shines most when she analyzes the fraught existence of women both from Austen’s time and own. The whole concept behind the book–focusing on Austen’s mean girls– humanizes the study of Austen and recognizes Austen not only as a moralist as some would paint her but also as an impressive interpreter of the human heart.

Before Makowski commences her analysis, she corrects the common mischaracterization of Austen as a modest woman whose novels are full of the delicate and virtuous. Granted that in comparison to the sensationalist writers of Austen’s time, her novels are subdued, lacking the “carriage chases, sexual abuse, or elaborate wedding scenes” (xviii) of the genre. But her novels are far from mellow. Makowski explains, “[T]he horrors Austen shares are remarkably like our own: a snub, some gossip, an ignored letter.” Makowski expertly argues that Austen’s writing highlights the subtle drama of ordinary female existence both in the Georgian era and our own.

For example, Makowski interprets Pride and Prejudice’s Caroline Bingley’s vendetta against the Bennett family as simple competition for partnership with a limited number of eligible bachelors. She explains that Caroline’s spiteful behavior toward Elizabeth and sabotaging Jane and Mr. Bingley is biologically natural if interpersonally nasty. Although viewing Caroline through this lens softens her slightly, Makowski’s suggestion that “we have it in our power to repair relationships with women if we really want to” does not strike me as entirely earned. Though reparations are made between Elizabeth and Caroline after the former’s marriage, this circumstance is not so much a model to be emulated as a dream to be wished for. Not to say that relationships can never be rehabilitated but “it is a truth universally acknowledged” that some relational improvements are beyond our power.

“Lady Susan,” an early novella by Austen, prominently features one of the most devastating relationships with a mean girl a woman can have–interacting with a mean mother. Lady Susan is a certified mean girl who mostly ignores but occasionally bullies her daughter Frederica. Makowski uses Lady Susan’s outrageous behavior as a jumping-off point for a discussion of the plight of mothers in the twenty-first century. The problem is simple: the standards for maternal behavior are impossibly high. No woman can live up to the everchanging standard for maternal behavior. This acknowledgment aside, Makowski suggests that some women like Lady Susan should not become mothers because they are too selfish. Using the therapeutic concept of Narcissistic Personality Disorder, she explains that much of Lady Susan’s selfish behavior fits the criteria for NPD. Lastly, Makowski suggests that those suffering under the thumb of their own narcissistic mothers would do well to seek out another older woman to serve as a mother figure, in the way Frederica turns to her aunt Catherine.

Additionally, Makowski embraces one of the oldest feminist issues that women are often each other’s worst enemies. Her accounts of her own sufferings at the hands of other women add credibility to the narrative without veering into self-pity. For too long some feminist writers have focused exclusively on male aggression against women when women have a unique proclivity for bullying each other too. Makowski compares Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s behavior with the behavior of a different kind of high-power woman in business. She observes that women who are in a masculine-dominated environment are often more critical of their female peers than men are because they see women as competitors for their unique place of esteem in a masculine world.

Makowski sets herself a challenging task to survey of Austen’s mean girls, review a wealth of sociological research on female aggression, and provide self-help style suggestions for how to solve each crisis of female life. Her analysis of Austen’s most dastardly villains, and a few more sympathetic mean girls, through a sociological lens, shines. Makowski’s personal reflections on the common struggles of women humanize her literary and behavioral conclusions, reminding us that she too has a stake in these difficulties. But her attempts to provide solutions such as stopping childhood bullying, forgiving our enemies, or walking away from impossible situations cannot resolve the mammoth problem of female aggression in the lives of most women. Nevertheless, Makowski provides a compelling look inside the lives of Austen’s women and ourselves in a delightfully personal, quirky read. Bitches in Bonnets is a cheeky and charming exploration of the complexities of female relationships in Austen’s world and our own. I’d highly recommend this book to those who enjoy Austen or those who don’t quite understand the nuances of female relationships but seek a deeper understanding through treasure of literature.