Stand on the Rock

If I could, I surely would stand on the rock where Moses stood.

I don’t know which rock the singer had in mind. The great rocky crags of Sinai? Some low-lying monadnock near the Burning Bush? A promontory extending into what the scholars now name the Reed Sea? Mere reading won’t suffice to identify it.

I do stand right now on a rock that, were I to see another in that configuration – rock underfoot, feet firmly on it, figure upright — I would have to envy. Just writing that line, I get a mental picture of arrows winging by my head. All the same, I’m not inclined to duck.

What’s happened? What’s changed? Well, I’m now preparing Confessions of A Young Philosopher for publication. Previously, it was turned down by every plausible publisher in the world accessible to me. Plus all the agents who handle memoirs. (Hey, move over Moses! I’d like a hand up.) Two well-regarded, highly experienced, well-connected figures in publishing – each in a position of unique influence at desirable imprints of university presses – have lent their good names to backing Confessions at their imprints, and been unexpectedly thwarted.

Have I got you interested?

Anyway, this resounding chorus of rejections has set me free to get the book illustrated. That has long seemed to me important to do. I should explain why.

Confessions of A Young Philosopher is the tale of a spiritual and philosophical pilgrimage. It’s also a tale of desire, but not the way such stories are told nowadays. The model for this kind of book is still St. Augustine’s Confessions. It was Augustine’s autobiography, a story of his long search for something to believe in – a solid rock where his uneasy soul could find attachment and rest. His search for spiritual safety took him, and us along with him, through the belief systems of his late classical times (354-430 C.E.). So his personal quest afforded later readers a tour of the thought-worlds of his day — and what he found wrong with each except the final one.

That’s exactly the genre of book I’ve written, which is why I titled it Confessions, in acknowledgment of its classical prototype. Among its novel features is this: so far as I know, no book in that genre has yet been written by a woman. If it has, I haven’t come across it.

All that prefaces the answer to the question of why I thought this book needed illustrations. Contemporary readers are unfamiliar with confession as a genre. The idea of an open-ended search for understanding, through the thought-worlds of the day, with that search motivating the seeker’s real-life choices, would not be a familiar motivation to find in books.

Despite what today’s novels and memoirs typically show, I would contend that most people are still actually motivated by the desire to know what is true and real. That’s as much the case for truck drivers as for academics. I’m not that peculiar, not that different. My readers of this blog don’t have trouble seeing their own experiences in mine. It doesn’t take specialized academic training to see and feel what I’m talking about. What’s rare is to read about it.

Reading matter today (as I saw from this weekend’s weary scanning of recent issues of the NY Times Book Review and the New York Review of Books), recognizes just a few things as humanly motivating: power or the lack of it and sexual fulfillment or, in its absence, the hunger for that. Oh yes, and “identity.” But identity also presented in terms of degrees of social or institutional power or gratification.

In current formulations, identities are not tied primarily to belief systems. In this, however, the current formulations are mistaken. Group identities, religious or ethnic, are ordinarily maintained by practices authorized and justified by beliefs. Let me say that again.

Group identities are typically maintained by what the group thinks is true.

Evidently, if you presented identity questions that way, a challenge would arise. The challenge of detecting and discerning truth. Which would render the identity question more subtle and complex than fashionable opinion-shapers are prepared to admit.

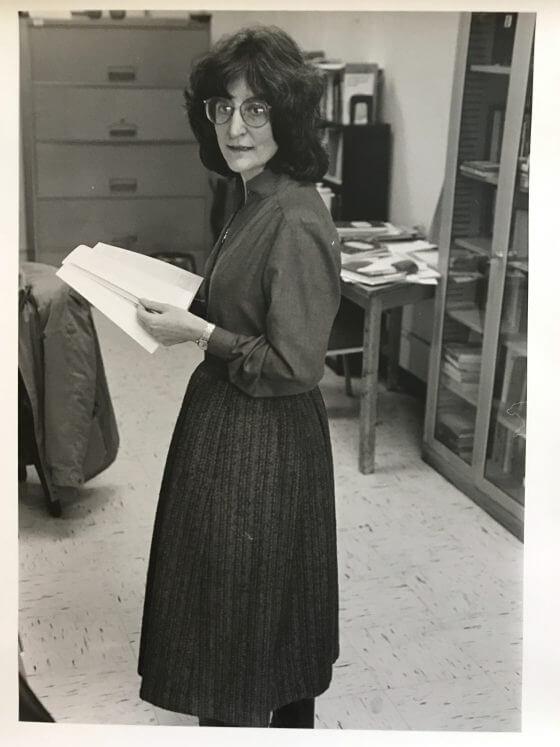

That’s why contemporary memoirists don’t write confessions on the Augustinian model. Since I did write such a book, illustrations are essential. They remind readers that what’s unfolding here is not a succession of abstract concepts, but a life adventure with a plotline! It’s a true story, about real people in their real places, seen through the eyes and delineated with the explanations worked out by a real young woman.

What’s “the rock” that I referred to earlier, the one I’m now standing on? Recently, in connection with preparing the book for publication, I’ve reread the whole manuscript. It had been a long time since I’d read it through, from beginning to end.

I was almost stunned. It felt as if I’d been struck by lightning. In my judgment, it’s a book of the highest quality. It addresses some of the shaping features of the culture, with intellectual and moral precision, and tells a woman’s true story, undeflected by the groupthink and ideological wrappings of the day.

I think that on the lives we live it sheds light.