T.S. Eliot and Reconversion on Ash Wednesday

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita . . .

There is something telling about man’s tendency to view his life as a journey, for journeys convey the reality of travels: A path, distractions along the way, and, as always, hesitation about the accuracy of the route (are we there yet? Did we choose the right path? Are we on the shortest path? Is this journey even worth it?). Waiting at the end of our journey is an envisioned destination, assuming we have not been there before since a journey is really only a journey if we do not know what lies at the end. It took Dante half of his life’s journey to realize he was lost; the straightforward path hidden by a dark forest that surrounded him. Had every step prior been in vain?

Ma per trattar del ben ch’i vi trovai,

Dirò de l’altre cose ch’i v’ho scorte

Not all was bad in these wild woods, Dante confides. He now understands that to tell us about the good that he found there, he must first begin by recalling the other things he saw. Within the framework of the Divine Comedy, we can say that before a conversion, there needs to be a period of “otherness” where we are alone, searching, doubting, thinking. These actions are certainly part of the journey, but in excess can become disorienting. When do we know that we are losing ourselves? Is there a specific moment where we realize we took a wrong turn? Or did we miss that turn moments ago, only to realize too late after a series of mistakes that we are lost?

These concerns supplement T.S. Eliot’s “Ash-Wednesday.” The poem is his journey poem, although some like to call it his “conversion” poem, which misguidedly conveys a sense of definitiveness about his religious faith. Sure enough, Eliot wrote “Ash-Wednesday” the same year he wrote “The Journey of the Magi,” in 1930, and Eliot had already converted to Anglicanism by this point. But is one ever fully converted?

In “Ash-Wednesday,” Eliot has started to walk out of the temporal city of The Waste Land, towards the eternal city St. Augustine calls the city of God—but he is not there yet. As his readers, we are first reminded of that familiar date where we commemorate the forty days that Christ fasted in the wilderness. This day we call Ash Wednesday asks us to dedicate time for repentance and to acknowledge our transience on this earth; here is where Eliot’s poem begins. “Ash-Wednesday” is replete with elements to analyze, but this essay will emphasize Eliot’s language to demonstrate his verbal depiction of his conversion journey, namely the importance of the first repeated words of the six poems. This verbal depiction of faith, moreover, is an idiosyncratic element of Eliot’s poetry that provides insight into this topic of a spiritual “journey” that needs to start, as Dante told, with descent.

I. “Because” and the Language of Cause

We enter a meditation in self-restraint. Part I opens up with a pensive sequence of reasons—but reasons for what? The first lines of the poem approach the question of faith in a causal form, “because I do not hope to turn again” (1); “because I do not hope” (2); “because I do not hope to turn” (3); “because I do not hope to know again” (9); “because I know that time is time” (16), still we do not receive a direct consequence to Eliot’s causes. What is clear at first, is that it is renunciation of something, and the triad “because” in the first three lines places a lyrical emphasis on this concept of cause. Eliot alludes the very first line to Cavalcanti’s famous line (and poem) “Perch’i’ no spero di tornar giammai,”[*] in which Cavalcanti is speaking to his “ballatetta,” his dear ballad, asking it to travel to Tuscany for him since he “does not hope” to return to that city.

Why does Cavalcanti need the ballad to go to Tuscany? His beloved lady is still there. Perhaps Eliot is also writing to a lady with the hopes that his ballad will reach her. Unlike Cavalcanti, however, Eliot’s inability to turn from wherever it is he comes is not physical. He mentions as much when he describes his renunciation of “desiring this man’s gift and that man’s scope” (4)—an allusion to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29. The sonnet is worth reading: The poet describes his dissatisfaction with his social status, recognizing that his “bootless cries” will not perturb “deaf heaven” (3), and so his comfort lies in thinking about his lady whose very thought makes the poet sing “hymns at heaven’s gate” (12).

In both of these poems to which Eliot alludes we notice an emphasis on the poet’s unfortunate life; both Cavalcanti and Shakespeare curse their fates in their respective poems and find solace in the thought of a woman. But who are these women? Lovers, or something more? It takes us as readers some time to realize that Eliot’s first references to Shakespeare and Cavalcanti in their romantic verses about women gradually morph into Dante’s spiritual—although still romantic—relationship with Beatrice.

If this first part is a meditation in self-restraint, it is important to clarify that self-restraint can be positive, such as in an ascetic form that rejects earthly pleasures in order to move closer towards a spiritual life (The Waste Land conveyed these initial thoughts), but it can also be a skeptic form of self-restraint that prevents Eliot from fully embracing his faith. The majority of part I of “Ash-Wednesday” demonstrates the latter. Eliot’s journey is faltering, the second stanza reveals how Eliot is interpreting and reinterpreting thought: “Because I do not hope to know again” (9); “Because I do not think” (11); “Because I know I shall not know” (12), Eliot continues to contradict himself by his own action. He says he cannot drink from a place—“there” (15)—that has a location where “trees flower, and springs flow” (15) because “there is nothing again” (16). Eliot flashes back and forth between glimpses of faith and emptiness; between moments of exaltation and disappointment; faith and nothing. But these limitations are self-imposed, demonstrating the difficult course of conversion.

There are moments in the first part of the poem where Eliot shows that he is being pulled back from faith. He proclaims in the third stanza how the world is nothing but earthly:

Because I know that time is always time

And place is always and only place

And what is actual is actual only for one time

And only for one place (17-20)

Of course, Eliot argued almost the exact opposite in Four Quartets thirteen years later. Still, he recognizes in “Ash-Wednesday” that these spiritual regressions, which are the consequence of his reasoning (i.e. thinking about what he “knows”), force him to “renounce the voice” (23) and instead “rejoice”—an intentionally blasphemous word choice—in constructing something “upon which to rejoice” (26). Eliot’s choice to use religious language to describe secular concepts of life make the third stanza so critical to the poem. In the previous stanzas, Eliot is telling us what he does not know and cannot hope to know, finally when he tells us what he does know, they are empty phrases. Such a word choice conveys a verbal depiction of the journey towards conversion; we doubt our path as we “know” the earthly one better.

But then there is a shift in the fourth stanza where we get to a reason for Eliot’s causal phrases. Eliot asks God for mercy and asks Him to help him forget those previous thoughts that he tries too much to “discuss” (29) and to “explain” (30). In this thought lies repentance for his previous moments of doubt, and Eliot recognizes the path he wants to pursue, where God teaches man “to care and not to care” (39), to accept what comes, and “to sit still” (40) to not try and disturb this sequence by seeking proof or evidence for his faith.

II. “Lady” and the Language of Duality

If you look at the structure of the first part, the first stanzas are separated in thought by their first word “because.” Verbally, “because” creates this staccato-ed sense of pacing, heavy, that mirrors what is weighing down his spiritual musings. This comes to an end, not surprisingly, in the fourth stanza where Eliot opens with a soft, lifting word, “and,” which he also emphasizes: “And pray to God have mercy upon us / And pray that I may forget” (27-28). When Eliot prays, his sound smooths out as it seems, but when he thinks again, his sound reverts to the previous form: “Because I do not hope to turn again,” (31) “Because these wings are no longer wings to fly” (35).

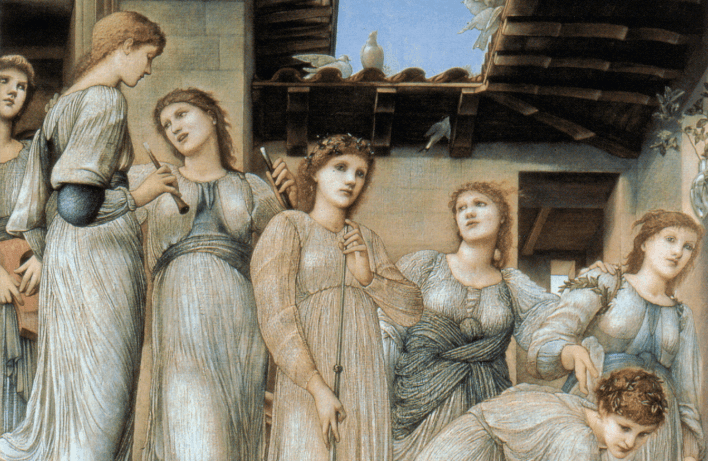

Compare visually and verbally how the second part of the poem opens. Eliot’s opening thought is a continuous flow which he even starts for us by giving us a direct beckon: “Lady,” (43). Eliot’s first word already demonstrates a different disposition from the previous section. The way in which we are introduced to a setting in which Eliot first references a woman is similar to part II Of The Waste Land, “A Game of Chess.” We are allowed, but only indirectly, into a scene. Eliot is taking to, or seeing (imagining), a lady as three white leopards are eating away at his flesh, organs, even his brain, leaving nothing but his bones. The earthly organs through which he fell prey to his vices—including his intellect—are now detached from him. Once all that’s left are his bones, he is now “chirping” (49) to live through God.

Eliot makes no mention of a soul; rather, it is his bones that outlive him, and it is his bones to which God speaks. There is something spiritual about bones, then, for in “A Game of Chess” Eliot also made a reference to bones that demonstrates that, for him, they are more than materials of our bodies: When the lady is asking him to say what he is thinking about, he responds, “I think we are in a rat’s alley / Where the dead men have lost their bones.” If bones have a relationship with God, then losing one’s bones signals a loss of hope for salvation. These bones in part II of “Ash-Wednesday” are like a memento mori for Eliot, as he envisions himself as nothing but a skeleton—a ghastly image to consider about ourselves that, nonetheless, has purging qualities.

Once Eliot ends his verbal path to envisioning his earthly death, he enters another meditation that almost seems to encapsulate the entirety of “Ash-Wednesday.” The poem speaks of oppositions, forms of dualism of seemingly conflicting elements within his faith and himself. “Ash-Wednesday” is itself lyrically presented in juxtaposing terms. In the poem (as in reality), Eliot does not know how to reconcile earth’s transient elements with the signs and glimpses at an eternal life that present themselves before him as visions. This problem is, to phrase it in Cartesian terms, a dualism between the mind’s perception of the world and the body’s interaction with the world; but it is a dualism that, perhaps, becomes unified upon the triumph of faith.

As Eliot encounters the “Lady of silences,” he begins to visually describe a fast path of juxtapositions. Whereas the previous stanza was continuous, but calm and contemplative, this stanza is quick and building:

Lady of silences

Calm and distressed

Torn and most whole

Rose of memory

Rose of forgetfulness

Exhausted and life-giving

Worried reposeful

The single Rose

Is now the Garden

Where all loves end

Terminate torment

Of love unsatisfied

The greater torment

Of love satisfied

End of the endless

Journey to no end

Conclusion of all that

Is inconclusible

Speech without word and

Word of no speech

Grace to the Mother

For the Garden

Where all love ends. (67-89)

Eliot’s language is now flowing, as if the words were coming to him intuitively without putting in too much thought. And yet, the series of juxtapositions are not supposed to make sense. As Eliot heeds God’s command to prophesy to the wind (64), he recites these contrasting phrases almost in a chant that comes in the absence of reason. The closer Eliot ascends to faith, the more of a dispensation of reason it requires. In trying to sense the completeness of faith he can’t help but describe it in opposing ideals.

Now, Eliot finally begins to ascend from his initial descent. Upon completing this vision, and this chant, Eliot’s bones are now “glad to be scattered” (91), his unity disrupted. As his bones speak, they acknowledge that there is little good in a fleshly inheritance on earth. It is nothing but “a blessing of sand” (92) where unity in “the quiet of the desert” (94) signifies nothing: “And neither division nor unity / Matters.” (95-96) The true unity that we seek requires an initial scattering; a separation of ourselves from ourselves.

III. “At” and the Language of Turning

Eliot opens every section of “Ash-Wednesday” by placing the reader in the middle of the story. Part III begins as Eliot is at the first turning of the second stair, reminding us of Dante’s Purgatorio. But which one was the first stair? A sense of temporality is displaced, for it takes Eliot a relatively long time to climb each stair. Although this is his shortest poem, it is the most taxing on Eliot. Here he uses words that evoke a struggle. Each stanza begins with a directional and location-specific marker to express the difficulty he finds there “At the first turning of the second stair,” “At the second turning of the second stair,” “At the first turning of the third stair.” Interestingly, Eliot stretches out the duration of these stairs.

As he ascends the first turning of the second stair, he looks down and sees “the same shape” (98), another copy of himself, down below still “Struggling with the devil” (100). He moves up these stairs rather quickly. Part III is the shortest poem of the six, in fact. As Eliot ascends to faith, he no longer falls for the deceitful mask of this devil who conveys hope and despair; in other words, Eliot’s conversion is no longer about finding hope, and his conversion is no longer for fear of despairing. These opposing concepts are only deceptive, for they do not get at the core of faith.

He continues to look down at his other self as Eliot reaches the turning of the second stair (103). Here, Eliot gives us explicit imagery of a spiral staircase leading up to somewhere. “Turning,” moreover, conveys a turning in direction as well as a turning in state of being: Eliot has told us he left a part of himself down below the first turning of the stairs, now the man walking up these stairs is presumably the same man, but a different form.

All goes dark. To our surprise, an upwards ascend does not get brighter, but completely dark. Eliot sees a window with a view to a “pasture scene” (110) where Pan is playing his flute (112). All of this is a “distraction” that eventually stops when he looks away from the bright outdoors. That bucolic vision continues to fade, “Fading, fading” (117), as he musters up strength “beyond hope and despair (117) to climb that third stair. Neither hope nor despair motivate Eliot to climb onward, yet he continues to turn.

IV. “Who” and the language of Visions

Time appears yet again displaced in part IV. The upward sequence is disrupted by a peaceful and mysterious “Who” that enters the meditation. This Who, and the rest of poem IV, convey a vision. Eliot describes a woman with Marian qualities, but not quite her since she is only “in Mary’s colour” (125) and “talking of trivial things” (126). Perhaps he is seeing Mary and her qualities in another woman, such is the role that love has with holiness; to see glimpses of God in others.

Upon recognizing this woman and her resemblance to the Virgin, Eliot has a revelation. These are some of the most beautiful lines in the poem, and their cadence turn into a dance:

Here are the years that walk between, bearing

Away the fiddles and the flutes, restoring

One who moves in the time between sleep and waking, wearing

White light folded, sheathing about her, folded.

The new years walk, restoring

Through a bright cloud of tears, the years, restoring

With a new verse the ancient rhyme. Redeem

The time. Redeem

The unread vision in the higher dream

While jewelled unicorns draw by the gilded hearse. (133-142)

Read these lines out loud. The end-word of each line carries us into the next one. Eliot separates almost every line with a penultimate comma. If we want to speed up, we are stopped by Eliot’s choice of punctuation, but we are still able to move through each last word repeated: “restoring” happens thrice, “redeem” twice. As readers, we are being pushed along Eliot’s vision to another. We meet the “silent sister veiled in white and blue” (143). She is standing between yew trees, and behind the garden god, Pan. Pan’s flute no longer plays, “breathless” (145), he is stunned by her presence. The lady bends her head at Eliot and leaves. These visions are all centered around the “Who” that we encounter in the beginning of the fourth poem, and they bring Eliot to another relapse.

V. “If” and the Language of Questioning

Eliot takes a break, as it were, from his journey. He now begins to think about the implications of all he has experienced prior to this moment. Eliot questions the likelihood that he will be able to fully come into faith, employing a self-limiting (again), circular logic about the futility of it. “If the lost word is lost, if the spent word is spent / If the unheard, unspoken” (151-152). But Eliot answers his own question: “Still is the unspoken word, the Word unheard,” (154).

Life on earth gives us moments where neither hope nor despair seem to matter, so bleak is the outlook. Whatever pointlessness we conceive about our efforts to believe and have faith, however, Eliot reminds us that The Word still exists, even if it is unheard. This lucid moment gives Eliot another insight:

And the light shone in darkness and

Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled

About the centre of the silent Word. (157-159)

Our creation and genesis provide a light in the darkness. True, our unstilled world continues to whirl the Word. Even though we have not yet learned “to sit still” as Eliot prayed in the first poem, we continue to rebel around a center of a silent Word: A word that continues to exist because it is “the word within” (155).

But this pretty discovery is not enough. What does it say to the convert (as he was) about the state of the world and our salvation? Eliot begins to ask, “Where shall the word be found, where will the word / Resound?” (161-162). In a sense of disappointment, he answers: “Not here, there is not enough silence” (162). Eliot continues to question his journey. He asks if the veiled sister will pray for all of the lost people, “Those who walk in darkness” (171). He asks, “Will the veiled sister pray / For children at the gate / who will not go away and cannot pray:” (174-176). The final stanza of the fifth poem concludes in this questioning fashion. It has taken Eliot four poems, representative of his long life’s journey, to reach a point of relative acceptance of faith; yet, in the fifth poem he regresses as he wonders about his salvation and the salvation of others. What says his final poem? Can he just entirely embrace faith in a joyous fashion after these serious thoughts about his death and humanity’s perdition? Eliot’s sixth and final poem answers in the most acquiescent manner.

VI. “Although” and the Language of Acceptance

Although I do not hope to turn again (187)

Eliot changes the opening lines of the poem that signaled a causal significance for his conversion (i.e. I want to believe because) to a noncausal, complacent acceptance for his conversion despite the practical reason for it (i.e. I want to believe although). Reaching Part VI of the poem does not by any means signify an end to Eliot’s journey or our own journey. Whereas before Eliot was “climbing” upwards for his faith, now there is a sauntering, meandering nature to his pace, “Wavering between the profit and the loss” (190). The lesson from his arduous journey? Faith is not something for which one ought to have a reason, neither hope nor despair; we will be grossly disappointed otherwise. Although it may not bring the knowledge or answers he seeks, Eliot concludes “Ash-Wednesday” accepting that all we can learn through faith is “to care and not to care” (214) and to “sit still” (215) for our peace lies in “His will” (217).

How does this poem help us to reflect on our death this Ash Wednesday? Eliot provides a telling detail in the closing stanzas:

This is the time of tension between dying and birth

The place of solitude where three dreams cross

Between blue rocks

But when the voices shaken from the yew-tree drift away

Let the other yew be shaken and reply. (206-210)

This triumph of faith that we considered to be the end-result of a full conversion does not come in “Ash-Wednesday.” That it may never fully come, but that we must continue in our struggle despite this fact, is one of the poem’s lingering lessons. Through Eliot’s spiritual struggle we see a reflection of our own struggles, which are checked by faith and knowledge in death. Our time on earth is what Eliot calls “the time of tension between dying and birth” (212), but notice how Eliot does not begin with birth, as we would most intuitively think. Surely, birth comes before death?

No, Eliot understands: Religious struggle comes to us as a time of tension that exists for the duration of our lives on this earth until we achieve what we are meant to do—to die, and be reborn. In this sense, dying comes before birth. To be reborn, we first need to learn to die, to accept death, and live life on earth as though we are meant to die so that we may be born after. “Ash-Wednesday” is Eliot’s journey through his own memento mori. His poem helps us to consider our earthly transience, just as Ash Wednesday reminds us of this same fact that our time on earth is passing. The rest of the path to reconversion—to birth and eternal time—is uniquely ours to take.