The Art World’s Greatest Scandal: An Unveiling of the Salvator Mundi

Reading Alex LaFollette’s Selling Leonardo: The Art World’s Greatest Scandal, A Memoir began by taking me back to a night in 2017. It was the night Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi sold at auction for $450.3 million at Christie’s. Despite substantial questions regarding the authenticity of the Renaissance painting of Jesus, the sale far surpassed the previous record for a work of art set at auction. The previous highest price had been Picasso’s Women of Algiers for $179.4 million in 2015.

Though the auction lasted less than 20 minutes, Christie’s embarked on a long marketing tour leading up to the night of the sale. Heralded as the Last da Vinci, Salvator Mundi is the last known painting by the master to be owned privately and is one of less than 20 paintings to still be in existence (the others are in museums). Before the sale, thousands clamored for a chance to see it at pre-auction viewings in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco, and New York.

While many leading experts agreed that the work was indeed done by da Vinci, some questioned whether it was partially the work of talented artists in the master’s studio. Some also raised concern about the extensive amount of restoration work done and its poor condition.

The entire event begged a very big question: “Why is a Leonardo in a Modern and Contemporary auction?” The answer: Because 90 percent of it was painted in the last 50 years. Not only did it look like a dreamed-up version of a missing da Vinci but various X-ray techniques showed scratches and gouges in the work, missing paint, a warping board, a beard here and gone, and other parts of the painting obviously buffed up and corrected to make this probable copy look more like an original.

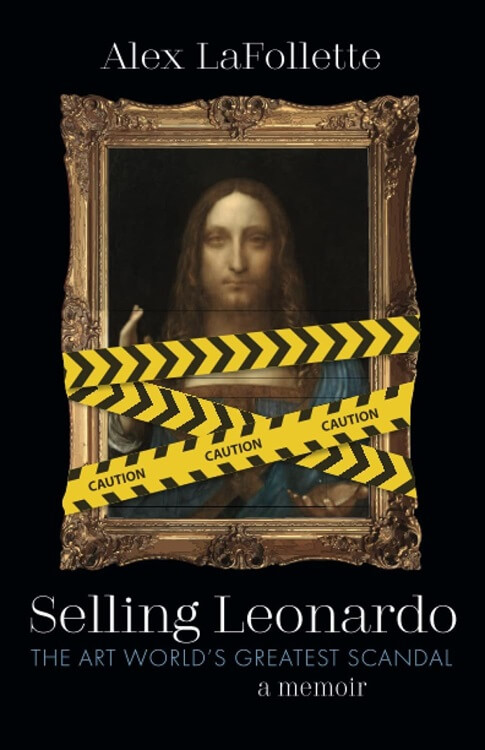

The painting is titled Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), and it is a portrait of a smoky, floating man in a blue robe looking directly at us, raising his right hand in blessing, holding a crystal orb in his left hand, and pictured against a black background. It is said to have been painted around 1500, when the real Leonardo would have been 48 years old and already the most famous artist alive.

On auction night, this small picture was auctioned off by Christie’s with massive jubilation. The opening bid was set at $100 million; this might even seem cheap if you can recall Damien Hirst’s 2007 For the Love of God, a diamond-and-platinum-encrusted human skull, was priced the same.

This explains why one Christie’s official rapturously primed the collector pump by wondering aloud if someone might bid “$2 billion.” In a world of imbalance, a world subtracted from values, from virtues, that could not have happened.

Promoting the sale is a glossy 162-page book with quotes from Dostoyevsky, Freud, and Leonardo, including several platitudinal Christie’s videos of enraptured gazers gawking in wonder at “the new masterpiece.” The auctioneers pitched it to Hong Kong clients as “the holy grail of our business, a male Mona Lisa, the last da Vinci, our baby, something with blockbuster appeal, akin to the discovery of a new planet, and more valuable than a petrochemical plant.” Then, as now, this is our world.

I am not an art historian or any kind of expert in old masters, but I have looked at art for almost 50 years and one look at this painting–even on my computer screen– told me this was not Leonardo. The painting is absolutely dead. Its surface is inert, varnished, lurid, scrubbed over, and repainted so many times that it looks simultaneously new and old, trapped between Leonardo’s time and ours. This explains why Christie’s pitched it with vague terms like “mysterious,” filled with “aura,” and something that “could go viral.” Go viral? As a poster, maybe. Refrigerator magnet. Coffee cup. A two-dimensional ersatz dashboard Jesus.

It smelled of sham. Experts estimate that there are only 15 to 20 existing da Vinci paintings. Not a single one of them pictures a person straight on like this one. There is also not a single painting picturing an individual Jesus either. All of his paintings, even single portraits, depict figures in far more complex poses. Even the figure that comes remotely close to this painting, Saint John the Baptist, also from 1500, gives us a turning, young, vibrant man with hair utterly different from and much more developed, in terms of painting, than the few curls Christie’s is raving about in their picture.

Leonardo was an inventor of — and in love with — posing people in dynamic, weaving, more curved, and corkscrewing positions, predicting the compositions of the matter to follow, Raphael, then in his 20s, and already being highly influenced, according to the great art historian of that time, Vasari, by his acquaintance Leonardo. Renaissance masters were all about letting figures interact with the surface and the structure of the painting, curving space, involving the viewer in ways more than an old-fashioned direct headshot. Leonardo never let a subject come at you all at once like the much more Byzantine, flat, forward-facing symmetry.

No other Renaissance master was involved with Byzantine portraiture like this either. They were all pushing way beyond that by then, reaching, reaching further.

Christie’s marketing had played the “golden ratio” card heavily. The golden section or golden ratio is said to have been developed almost 2500 years ago and was widely employed in ancient Greek art, which had a huge influence in the Renaissance. Basically, it is a mathematical system of measuring space whereby rectangles and proportions within the painting can be divided into an almost endless fractal series of repeating smaller rectangles, squares, ovals, and the like.

Christie’s painting was riddled with this proportion. However, I agree with LaFollette that no great artist worth their name would stoop to being this obvious, especially this far into their career when they had total freedom to do whatever they liked and had a lifetime of always doing it in increasingly original ways. All those who were/are enthralled by the Salvatore Mundi being a perfect golden section need to slow down, take a breath, and see the golden section can be imposed one way or another on almost any image.

Leonardo, who was nothing if not an inventor every time he came to a new surface of any kind, would have been laughed out of Italy.

By 1500, Michelangelo had already completed his tremendous Pietà in Rome and was in Florence working on the David. Botticelli was also on the scene working. It is hard to imagine that da Vinci coming to Florence and being around the young Michelangelo — who was being hailed as “the new da Vinci” — would suddenly have gone reactionary, producing a far more conservative, backward-looking picture.

These artists were as competitive then as they are now.

When Leonardo sat on the committee to decide where the still-unfinished David was to be situated in Florence, he voted against it, giving it the pride of a place it eventually won, next to the Palazzo Vecchio. In addition, if we are to believe this picture was made around 1500, that means Leonardo had already surpassed more primitive portraiture ideas like this, many times over, including in his many Madonnas, his beautiful Portrait of a Musician from 1485, and the two great Virgin of the Rocks, painted between 1483 and 1499. Not to mention his multi-spaced, multi-portrait, consciousness-expanding Last Supper, completed in 1498.

It would have made no sense to suddenly have Leonardo come to Florence to become a hack painter of post-Byzantine portraits, which is what the narrative being promoted by Christie’s rather unsubtly suggests. In fact, we know Leonardo did just the opposite— in 1502, he painted the Mona Lisa. Salvator Mundi does not fit into his work no matter how you try to twist things. If we want to give the esteemed auctioneer the benefit of the doubt, however, let us be generous and say this work does date from that time and Leonardo did maybe paint a stray strand of hair and/or a hand. Even if this holds, the rest of the painting — including the intricate patterning and clear glass, which would have been a specialty of numerous studio assistants at the time — is still sensuously and physically inert, dead on arrival. I will admit the painting is spooky and olden-looking like a lot of pictures of Jesus blessing saints, another argument against this being made by an artist of maestro Leonardo’s epic skills.

This kind of salesmanship and its communication campaign is an old game: pure and simple greed, an irresponsible, intentive, and confidence game that defrauds a mass audience into thinking it is “appreciating” an old master when it is all a big smoking spectacle and mirrors.

The idea that the best test of a painting is to place it under the hammer at auction simply tells you how out of touch Christie’s has become, especially how out of touch culture has become.

It is also a sign of a new system of authority, a sad sign of how much power auction houses have acquired that one of them is pushing a new work by an old master — a work some experts accept or speculate, and those who are skeptical raise no argument(s).

Those experts are probably thinking, “Well, academic scholarship is fickle, changing every 20 years and others will correct this,” not wanting to rock the already splintering, institutional-investing boat.

As in the wider world where people sit by for fear of losing position, it is no wonder many old master experts are keeping quiet, not saying much of anything. And, of course, no one at Christie’s can say, “Wait a minute, guys.” I know many of the people there, and they are all as passionate and knowledgeable about art as anyone I know. But if any of them think anything is askew, they are not ones to set their jobs out on a limb saying, “Nothing is going to change anyway, and that train has already left the station, bound for the Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

But all’s well that ended well, as it was bound to end well. By which I mean it will go poorly for Christie’s. No museum on Earth can afford a dubious picture like this at these prices — even if it is true that any institution or collector who buys this painting for however much money will be able to foist it on viewers center stage as “the last da Vinci” and make an obscene amount of money.

For any private collector who was conned into buying this picture and places it in their apartment or storage, it served them right. (Though it is hard not to think of what better good that $100 million — or $2 billion — could do.)

As for Christie’s, as an auction house, it should be shunned by the art world, recognized for what it is: a hostile witness to authentic art.

I will not spoil the book for you by telling you who actually ended up buying the painting. (Although one of this world’s truly evil actors now owns it.) And I will not tell you here what high tech analysis of the painting actually revealed, (though it may or may not surprise you.)

I will let Andy Warhol have the last word in summing up what is really going on; when he heard that the Mona Lisa was coming to New York in 1963, he said, “Why don’t they have someone copy it and send the copy, no one would know the difference.”

All of this and so much more is packed into the slim but potent book called Selling Leonardo by Alex LaFollette. It is a gripping and meticulously researched exposé that delves into the enthralling world of high-stakes art auctions, international intrigue, and the enigmatic masterpiece, the Salvator Mundi.

LaFollette’s book is a treasure trove for art enthusiasts and intrigue seekers alike, unraveling the web of secrecy surrounding this incredible work of art and the multi-million-dollar transactions that brought it to light.

LaFollette’s storytelling is immersive; he weaves a thrilling narrative that unveils the secretive world of art dealers, collectors, and the rich and powerful. He takes readers on a global journey from the dusty corners of art restorers’ studios to the glitzy auction houses of New York and London, making every page a revelation.

At the heart of this mesmerizing tale is the Salvator Mundi, a painting believed to be the work of the Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci. LaFollette masterfully traces the history of this once-forgotten masterpiece from its rediscovery in obscurity to its record-breaking sale for millions of dollars. The author leaves no stone unturned, providing a comprehensive history of the painting’s attribution, authenticity debates, and its role in the art world.

One of the book’s most captivating elements is its exploration of the controversial characters involved in the painting’s journey. LaFollette introduces readers to a cast of art dealers, scholars, collectors, and auction house experts, all envying a piece of the pie. With his vivid and expertly crafted descriptions, he manages to humanize the most enigmatic figures in art world drama, providing insight into motivations, passions, and cunning strategies.

The book exposes the dark mystery that shrouds the Salvator Mundi’s provenance, adding to its allure. LaFollette takes readers on a globe-trotting adventure, unearthing secrets and connections that span continents. It is a true tale of art detectives at work, chasing clues, hunches, and whispers across time and space, revealing the layers of intrigue that surround the painting.

The story is really a picture of our times; it is complete with copy cat forgers, media glitz, great, corrupt princes and their power and wealth, oligarchs, immense palaces, and a final discovery. It is also a great morality tale: public opinion, due especially to our leviathan social media complexes, is easily pushed in one direction or another. The minds of the masses are as short grass in the fast autumn winds. All the while in these mysteries, there are always showrunners— mega committees, governments, boards of directors— making sweeping changes that can easily fall prey to a counterfeit painting, false promises of a political candidate, or another product or service pitched to us on an infomercial.

The allure of Selling Leonardo lies not only in its exploration of the Salvator Mundi but also in the revelation of the secretive, high-stakes art world. LaFollette provides readers with an insider’s view into the machinations of the art market, the behind-the-scenes dealings, and the pressures and politics that shape the fate of masterpieces. It is a world where fortunes rise and fall with a blind of an eye, and where authenticity can be a matter of opinion rather than fact.

LaFollette’s impeccable research is evident in the way he breaks down complex art historical debates and provides a balanced perspective on the authenticity of the Salvator Mundi. He navigates the reader through a labyrinth of evidence and counter-evidence, leaving room for readers to form their own opinions about the painting’s true origins.

Selling Leonardo: The Art World’s Greatest Scandal is a completely engrossing exploration of art, commerce, and intrigue. Alex LaFollette’s storytelling is as captivating as the subject matter itself, and his meticulous research and attention to detail make this book a must-read for anyone fascinated by art history, the art market, or simply a thrilling, real-life mystery. Whether you are a seasoned art connoisseur or a newcomer to the world of art, this book will captivate you from the first page to the last, leaving you with a newfound appreciation for the art world’s greatest scandal.