The Birth of Yoda: Manichaeism and the Jedi Religion

“No matter how esoteric an artist you are, you’re still playing for an audience. If you only play to 10 people, then, maybe you’re a high artist” – George Lucas

“For over a thousand generations, the Jedi Knights were the guardians of peace and justice in the Old Republic. Before the dark times. Before the Empire.”

“Now the Jedi are all but extinct.” –Obi Wan Kenobi, A New Hope

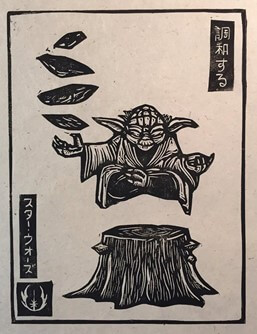

In honor of Star Wars Day, I would like to discuss the birth of Yoda and the Jedi order. I mean the original Yoda, not “the Child” (a.k.a. Grogu) whom the Hollywood Reporter called the “Dalai Lama in toddler form.” (As a fifty-year-old baby, “the Child” is chronologically older than the entire Star Wars franchise.) I will instead reflect on the birth of the esteemed 900-year-old rebel leader from whom Grogu inherited his original nickname, “Baby Yoda.” The elder Jedi Master Yoda (like Grogu) is a Force-sensitive long-lived alien of mysterious pedigree. We have no idea where Yoda’s species originated. The famed planet Degobah was merely Yoda’s refuge from persecution, and where he abandoned his corporeal form, dissolving into a luminous body and becoming “one with the Force” during his second act in Return of the Jedi (1983). Yoda’s species and his birthplace are unnamed in any canonical Star Wars story. Could Yoda have originated in a Buddhist-Christian synthesis in third century Persia?

Yoda is brain-child of “Buddhist-Methodist” filmmaker George Lucas. Lucas openly acknowledges that Yoda’s Force Religion (“Jediism”) blends Buddhist and Christian esoteric lore. Jediism now has real-life adherents (whether serious or otherwise) and one modern UK census (2011) revealed that Jedi was the seventh largest religion in that kingdom, dwarfing British Scientology (another so-called “religion” founded by a science-fiction auteur).

In Jediism, world-mythology merges with adventure and fantasy fiction, combining Akira Kurosawa’s Buddhist and samurai themes with J.R.R. Tolkien’s Christian allegories. A historical Buddhist master is the most likely model for Yoda. We can only guess which varied influences account for Yoda’s extreme longevity. Biblical Methuselah lived more than 900. Tolkien’s Gandalf lived more than 2000. The historical second-century Buddhist patriarch Nagarjuna lived to more than 700 (according to legend). Padmasambava (Tibet’s “second Buddha”) allegedly dissolved like a Jedi into a rainbow body of light. The oldest attested ending of the oldest attested Christian gospel (the “short” ending of the Gospel according to Mark) depicts Jesus of Nazareth simply disappearing from his tomb with the witnesses running scared.

British Jedis might outnumber Scientologists, but Lucas was not the first savant to forge a universalizing hybrid religion. Yoda’s esoteric roots are ancient. Yoda’s very name may in fact be derived from an obscure Christianization of the name “Bodhisattva” (lit: “Enlightenment Being” a.k.a. one who will attain Buddhahood), distorted in transit to Christian Europe on the trade routes, and preserved among the various Buddhist and Christian scriptures sacred to a different ancient religion: Manichaeism.

Gnosticism and Manichaeism: Religion of Light

Tolkien’s “Catholic myth”, Lord of the Rings, deeply influenced Star Wars. Tolkien’s wizard Gandalf seems to be one of Lucas’s primary models for Obi Wan Kenobi. Paralleling Kenobi’s ill-fated duel with the Sith Lord Vader on the Death Star, Gandalf also died in single combat against an enemy clothed in shadow (the Balrog Durin’s Bane who lived in the Mines of Moria). He was later resurrected and arrived during the crucial battle scene, having been transformed into a luminous white form. His triumphal return to aid the war effort proved decisive at the battle of Helm’s Deep, just as Kenobi’s transcendent Force Ghost proved to be Luke Skywalker’s decisive aid at the Battle of Yavin.

Nonetheless George Lucas’ homage to Tolkien is clearly Gnostic, not Catholic or Orthodox or Protestant. (“Gnostic”, referring to esoteric knowledge, is a somewhat controversial umbrella term for various early Judeo-Christian heresies most of which can be characterized as “anti-materialist”). At the conclusion of Return of the Jedi, the luminous resurrection of three deceased Jedis (Yoda, Obi Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker) differs from mainstream Christianity’s tenet of material/bodily resurrection. It instead conforms closely to Gnosticism’s non-material/spiritual resurrection. The Force Ghost is pure light/energy, not “crude matter.” The overtly Gnostic implications of Jedi resurrection have been known to trouble Christian apologist Star Wars fans. The similarity between Jediism and Gnosticism runs deep.

Mani of Babylonia, “Apostle of Light” (216-274), founded Manichaeism, the most successful Gnostic Church in history. Raised Jewish-Christian in Sassanid Persia when Buddhist missionaries were active, Mani syncretized three religions: Christianity, Buddhism and Zoroastrianism. Manichaeism as a distinct syncretic faith tradition endured more than 1000 years in several continents, teaching that light-particles (spirit) and dark-matter (flesh) were in perpetual conflict in the universe. Only Manichaean ascetics were capable of separating light from darkness via disciplinary practices closely mirroring both Buddhist and Christian monasticism. Indeed the mysterious origin of Christian monasticism in Egypt occurred more-or-less simultaneously with the establishment of Manichaean monasteries (modeled after Buddhist ones) in the same region. One Aramaic word dara, referred to Buddhist, Manichaean and Christian monasteries in Western Asia during this period.

Mani considered himself the direct successor of the Buddha and an Apostle of Jesus Christ in the mold of Saint Paul, following the radical Paulinist orientation of many Gnostics. Like some modern critical religion scholars, he regarded Paul’s early vision of Jesus’s resurrection as purely spiritual, not physical (in contrast with the explicitly physical resurrection described by the author of the Gospel according to John). This and other differences with normative Christianity marked Manichees for persecution when state-Christianity arose in Europe and North Africa. Over roughly a millennium of proselytization on global trade routes, the Manichees (like the Jedi) were systematically hunted down and destroyed by agents of various theocratic empires.

Manichaeism was chameleonic by nature. It swiftly morphed into crypto-Buddhism and crypto-Christianity. Elements of Manichaeism may have survived underground within other world faith traditions and possibly helped to spawn several major rebellions against various world empires. Manichaean missionaries harmonized Western and Eastern religious texts in ways that presaged George Lucas’s creative “Buddhist-Christian” projects. This Manichaean harmonization led Jesus to be called a Buddha in East Asia, and led the Buddha also to be venerated as a Christian saint in Western Europe. Astonishingly, Jedi Master Yoda’s name is found within a medieval Manichaean Christianization of the historical Buddha’s biography. George Lucas might confirm or deny this; my hunch is that he may have chosen to model “Yoda” from the Arabic, Georgian and earliest Greek form of the name of the Christianized Buddha “Yodasaph”, enshrined within this syncretistic esoteric literature.

Manichaeism in the West

In a brief moment of social solidarity between Christians and Manichees, Emperor Diocletian (the famous persecutor of Christians) burned Manichaean clergy alive (along with their books) in circa 297. After Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan granted general freedom of religion in 313, several decades would pass when Christian and Manichaean monks and nuns freely lived cheek-by-jowl within the Roman Empire. But the tide would later turn against the syncretic heresy. Ex-Manichee Augustine of Hippo (354-430), converted to normative Christianity in 386 and condemned his former religion. Coincidentally, this was just one year after Christian Emperor Maximus executed a Manichaean bishop for heresy in Southern France in 385. Augustine’s innovative interpretations of the Old Latin texts of Paul’s Epistles may have been indebted to his formative years as a Manichaean lay-cleric. Like Mani’s Christology, Augustine’s Christology was heavily influenced by Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. One of Augustine’s key contributions to Western Christianity is the concept of “Original Sin”, which resonates with Mani’s teaching by suggesting that human flesh is tainted via a primordial corruption. Manichaean influence is thus “baked in” to Western Christianity.

Facing extreme persecution and losing their distinct identity, Western Manichees were violently compelled to stop revering the person of Mani himself but nonetheless retained his dualistic theology. Heretical missionaries plied the trade routes from the Balkans and Asia Minor (i.e. the Greco-Persian buffer zone) and spawned many new dissident European “crypto-Christianities”, which were often simply called “Manichaean” by Catholic opponents. Rebellious “neo-Manichaean” offshoots in Southern France were targets of inquisitions and domestic crusades after 1209. Neo-Manichees were difficult to differentiate from neighboring Christians in the same towns. A Latin slogan Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius. [“Kill them all. God will know His own.”] is attributed to the commander of a massacre in July 1209. Neo-Manichees (like later Protestant Huguenot rebels) networked via the textile trade and conversed with eastern foreigners in Languedoc’s ports. Villages in Southern France (targeted by inquisitors) became hotbeds for Reformation theology, bloody battlefields of Early Modern religious wars. Most Protestant leaders espoused normative Trinitarian Christology, but the grassroots soldiery—early-Protestant layfolk—embraced many nonconformist (non-Trinitarian) Christological heresies on the neo-Manichaean belief spectrum.

Manichaeism in the East

The prophet/founder Mani was martyred in third-century Iran. He was flayed alive by Zoroastrian theocrats in a manner precisely parallel to the legendary martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew by the Zoroastrian crown in Armenia. Manichaeism in Persia was then violently suppressed by the Sassanid Empire until the Islamic period. Manichaean and Zoroastrian institutions arose side-by-side, and drew from ancient Persian mythology. Early Islam in seventh-century Arabia adopted titles/slogans from Manichaeism and codes for laypeople. The third Abbasid Caliph, al-Mahdi suppressed Manichaeism after 780, and the religion subsequently declined in the Islamic world.

Central Asia’s Uyghur Kaghanate established Manichaean theocracy (763-840), and influenced the earliest phase of Buddhist transmission in Tibet. Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen (ca. 755-804) promoted orthodox Buddhism and suppressed Manichaeism. His court issued an imperial edict condemning the Manichaean heresy against Buddhism.

The early and rapid rise of Manichaeism in China abruptly ended in 845 when Daoist emperor Wuzong of Tang purged “foreign” religions. He defrocked clergy, razed temples, and seized assets from Buddhists, Manichaeans, Orthodox Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians. Wuzong’s edict killed most Chinese Manichean clergy. Buddhism was deep-rooted and eventually recovered, but Manichaeism only survived as underground “crypto-Buddhist” sects within Chinese folk religion alongside Confucianism and Daoism. Militant Manichaean-Buddhist rebels, the White Lotus sect, overthrew the Mongols, spawning the Ming Dynasty between 1352 and 1368. The White Lotus rebels remained as a Ming constituency and were so fearsome that Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang officially banned Manichaeism in 1370. White Lotus rebels struck again (1796-1804) against the Qing Dynasty, prompting the Qing rulers to ban Manichaeism until 1912. Manichaeism, no longer distinct, merged with Daoism and Buddhism. Ancient Manichaean temples morphed into modern Buddhist temples. Sacred texts and images from the Manichaean libraries were recast as Daoist-Buddhist documents. Via this process of gradual transformation, a tiny spark of Mani’s “Religion of Light” still burns within Chinese folk religion.

Yodasaph: Manichaean Buddha of Christendom

Manichaean texts were translated into many languages, bringing Buddha’s biography to Western audiences. Various Buddhist scriptures gave rise to the hagiography of Barlaam and Josaphat, a Christian legend which swept medieval Europe. Sanskrit “Bodhisattva” was transcribed into Middle-Persian and thence into Abbasid Arabic as “Budasaf” in the eighth century. A ninth-century Georgian monk transliterating Arabic did not notice diacritics differentiating B [ب] and Y [ي]. Thus Arabic “Budasaf” became Georgian “Yodasaph.”

A Greek monk faithfully transcribed Yodasaph as “ΙΩΔΑΣΑΦ” but a later scribe conflated Greek delta [Δ] with neighboring alpha [Α], standardizing “Joasaph.” Eleventh century Latin translators mistook it for Hebrew “Yehoshaphat.” Thus “Bodhisattva” became “Josaphat.” The intermediate form “Yodasaph” occurred precisely at the crossroads where his Buddhist pedigree became obscured, just as Christianized neo-Manichaeism rapidly ascended in central Europe. Josaphat was popular throughout Europe (among Orthodox/Catholic and heterodox alike), but he was especially revered by the rebellious European heretics hunted by imperial Albigensian crusaders.

Call it a hunch. I strongly suspect Lucas read an old standard source. Joseph Jacob’s 1896 edition of Barlaam and Josaphat which plainly illustrates the Manichaean-Arabic etymology of Yodasaph. Did Lucas uncover this name when he studied anthropology and literature as a community college student in Modesto in the 1960s? Or did he encounter it later when he was doing research while writing the screenplays?

Alternative Explanations?

There is another popular etymology for “Yoda.” Some say Yoda’s name is a nod to his puppeteer Frank Oz’s Jewish heritage. “Yoda” means “to know” in Hebrew. “Jedi” is an Anglicized rendering of “Yehudi” (“Jew”). The successful Maccabean Jewish rebellion against the Seleucid Greeks in 140 BCE is another good analogue for the Jedi-led rebellion against an evil Empire. I imagine both names could be Yoda’s eponyms, like a parent naming a girlchild “Ruth” after both Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Ruth Benedict, or a boychild after both Oscar Wilde and Oskar Schindler. Lucas was inspired by Joseph Campbell’s Hero with A Thousand Faces (1949). As far as Yoda is concerned, the more faces the merrier.

Conclusion

I could be wrong about Yodasaph (the Christianized Bodhisattva) being the direct paternal ancestor of Grogu and Master Yoda. If so, it is a spooky coincidence. Psychologists might be better than historians at assigning meaning here. The enduring impact of science fiction is more than the sum of its esoteric parts. As my colleague and co-editor Mark Peterson recently wrote: “Our myths, our narratives, condition what we find to be meaningful and, therefore, which facts about the world are meaningful.” Baby Yoda (“the Child”; Grogu) is a redemptive figure for having rekindled fans’ unified enthusiasm for the Star Wars franchise at a moment when division of the fanbase was never greater. The uncluttered, steady pace of the storytelling in the newer televised series, and the rise of a more consistent trend in character development, is a refreshing return to what made the original trilogy a cinematic classic. For that, I say “Om mani padme hum.”