The Drama of Western Music

When thinking or writing about Western classical music, we are so often concerned with touting its brilliance and greatness that we seldom place it in context with other types of music in the world so as to understand what is really unique about it. While I don’t claim to be too familiar with the multifaceted entity known as “world music,” I know what I have read from experts on the subject and what I have experienced in listening to Western classical music throughout my life. And the consensus is that of all the music of the world, Western classical music is distinctive by virtue of its complexity, both technical and emotional, and for projecting a compelling sense of drama and narrative. Particularly from the Viennese Classical period (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert) onward, the symphonic and other instrumental music of the Western tradition embodied a pulse-quickening sense of drama impelled by the opposition of contrasts and patterns of tension and release.

These contrasts and patterns may be expressed on a number of levels. One is the dichotomy of consonance and dissonance, with dissonance representing tension (whether emotional or physical or both) and consonance representing relaxation, relief, or repose. Another possible source of contrast is between the two themes, or subjects, in a Classical sonata-allegro form (as heard, for example, in the first movement of many symphonies), with the development or working-out of these two themes bringing a sense of effort or struggle that is finally resolved in the recapitulation (restatement) of the themes in their original key, bringing a sense of homecoming after a wide-ranging journey, or the summation of an exhaustive and emotionally appealing argument.

Yet even before the Viennese Classical composers there was often intense drama in Western music. Think of the expressive madrigals and operas of Monteverdi in the early Baroque, and the later gothic complexity of the contrapuntal and harmonically rich music of Bach, both secular and sacred. A Bach fugue often conveys a mounting intensity that carries you along its path with a sense of unerring logic, not letting you go until the final note brings the inevitable resolution. In the Romantic era composers like Berlioz and Wagner exploited further the storytelling potential of music, creating very elaborate musical-poetic narratives. Wagner in his “music dramas” like Tristan and Isolde raised musical tension almost to its breaking point through harmony and long timespans, depicting the emotions of yearning, desire, and rapture. In this way, Romanticism was in some sense the fulfillment of the dramatic impulses in Western music that had been gathering strength for a few centuries.

As I hinted before, much of the drama in classical tonal music comes about from the use of keys. Without wading deeply into music theory, suffice it to say that starting from a tonic (home key) and modulating to various other tonal centers before returning to the tonic creates an unmistakable sense of a journey. Harmonic relationships—as felt in various gradations of consonant and dissonant chords—are also a source of tension and release, used by Western composers to imbue music with emotional meaning. Instrumentation, felt in the distinctive character and color of various instruments or human voices, can also be used to create tension or opposition. The venerable art of counterpoint, in which different melodic lines are sounded simultaneously, can symbolize a dramatic dialogue. So can the musical structure of sonata-allegro form, which is a sort of argument using musical tones instead of words.

Conversation, dialogue, story, drama, movement, conflict and resolution, tension and relief; a structural edifice of notes building toward a musical goal or telos: these are the hallmarks of our civilization’s music. They are not qualities are not inherent in the traditional music of other civilizations. The classical music of India or China, for example, does not “develop” in the way that we are used to in Western classical music; rather, it projects a sense of steady calm based in variations of simple harmonic and rhythmic patterns. An Indian raga consists of improvised melodic patterns performed over a drone or tonic note designed to create a unified mood or atmosphere in the listener. Such music does not tell stories or portray outer or inner conflict. One formula has it that African music is predominantly rhythmic and physical, Asian music melodic and spiritual, and Western music harmonic and emotional. This may be an oversimplification, but there is undoubtedly truth to it. And I think that the emotion and drama inherent in Western music express, more particularly, cultural ideals of the Greco-Latin West derived from both classical antiquity and Christianity. From the beginning Western culture has been infused with the sense of story, as seen in the mysteries of the Christian faith as well as in Greek drama, myth, and philosophical dialogue. Story and dialectic imply the conflict of opposing forces or ideas, and this is the source of the dynamic qualities of Western music.

But this is not the whole story. Contemplation, simplicity, and reverence have also existed in Western music side by side with the emphasis on emotion, drama, and organizational complexity. Beethoven is famous for his dynamic qualities, yet many of his late works—like the piano sonatas—have long sections of meditative, otherworldly calm. From the 20th century, I think of works like the ending of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, in which time seems to stand still in a rapt contemplation of eternity, or the final movement of Copland’s Piano Sonata, a similar moment of timeless stillness. Certainly, the music of Bach is not constantly dramatic, and much of his music creates a sense of eternal cosmic order, a kind of spinning out of creative energy. Before Bach, Palestrina and other Renaissance masters weave a spell of contemplation through their polyphonic interweaving of melodic voices, expressing corporate faith and conviction more than individual emotion and a sense of eternity more than the storm and stress of earthly life.

The fact is that the dramatic strain in Western music really started with Claudio Monteverdi in the early Baroque era, with his efforts to illustrate verbal texts and individual emotion in music. This has a decided counterpart in Renaissance humanism and Baroque visual art, with their embrace of the external world and human emotion, inspired equally by classical antiquity and the Christian Gospel. Monteverdi and his fellow musical-dramatic experimenters were explicitly aiming to recreate Greek drama in modern form in their new invention, opera in musica, later “opera” for short.

Opera would blossom into one of the major Western artforms, a vehicle for heightened dramatic expression and storytelling through the power of music. Christian fervor plus the humanism that lay behind the invention of opera resulted in Bach’s Passion oratorios, one of the supreme Christian (and Western) musical expressions.

It could be argued that before Renaissance humanism and Baroque emotionality, the art of the West was influenced by more contemplative ideals, as we experience in medieval altarpieces or in Gregorian chant. It could be that our entire musical tradition since the Renaissance is the fruit of humanism, or perhaps of the interaction of classicism and romanticism—a contrast between the conception of music as a reflection of universal order and harmony (both in the cosmos and in the human soul) and the conception of music as an expression of the drama of the soul and everyday life.

For some, the drama of Western music might even be a stumbling block. The strength of a particular artform can become its weakness through over- or misuse, and if one can speak of Western classical music as having a weakness, perhaps it is an overconcentration on development leading to a certain busyness and overactivity. Western classical music has achieved wide acceptance and familiarity in Asia, but it is said that when Asian listeners first encountered orchestral music, they found it too loud, busy, and overcomplex. A case could be made that, on balance, Western music since the Baroque could have used a bit more contemplative calm and simplicity to offset the goal-oriented logic and rhetorical drama. Too much emphasis on the development of themes and motifs and the pursuit of rhythmic activity in music can become literally wearisome. This emphasis has its peak, perhaps, in the atonal Second Viennese School, whose compositions function as an incessant development or variation of musical motifs and the manipulation of “tone rows.”

In more recent times, composers associated with “spiritual minimalism” (Arvo Pärt, John Tavener, et al.) have turned back the clock, writing a more meditative, more static, less goal-driven type of music than we typically find in the Western tradition. Some of this music is explicitly inspired by an eastern, and often Eastern Orthodox Christian, aesthetic. Listeners may differ as to whether they find these works a spiritual refreshment in a troubled world or barrenly minimalistic.

For some time, in fact, experimental Western composers had looked to the east as the source of a calmer, putatively more wholesome aesthetic. Early in the 20th century the Impressionists Debussy and Ravel were influenced by the hypnotic qualities of the gamelan, the traditional percussion orchestra of Indonesia. We can hear this influence in a piano piece like Ravel’s Jeux d’eax, which hardly goes anywhere but simply creates a shimmering burst of sound with its changing harmonies. Here again, the slowing and calming down is the result a Western composer turning eastward for inspiration. This meditativeness informed as well the music of Olivier Messiaen, a modern composer highly admired (though his music tends to baffle me).

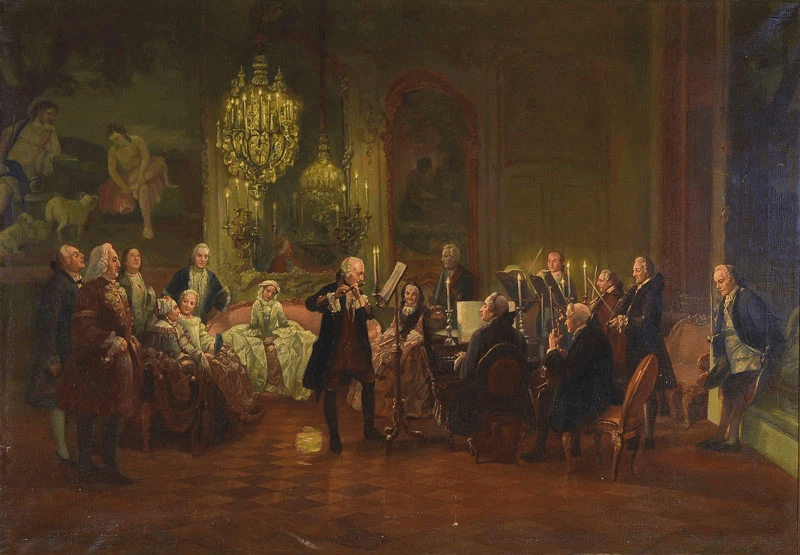

Yet the mainstream tradition of Western music is one that assumes that a musical piece must go somewhere and take you there. This inherent drama seems to me to have spread to the historical and stylistic development of the artform, as constant experimentation and changes in taste have led composers and musicians to devise new effects, move and stupefy audiences with sonic splendor (as in the antiphonal effects of choirs and instruments in St. Mark’s Cathedral, Venice, in the early Baroque), and even to face off in opposing stylistic camps like political parties (think of Brahms versus Wagner, or Stravinsky versus Schoenberg), making the study of music history exciting and dramatic in its own right. Like Western history in general, Western musical history has packed a lot of eventfulness and change within a few short centuries. Classical music performance is also imbued with drama, with physical gesture allied to the musical expression, always of course governed by a classic grace, restraint, and decorum.

For all the dynamic (vigorously active, energetic) aspects of our musical heritage, however, it would be worthwhile to listen for the still, small moments too. We will realize that the classical tradition is quite complete and whole in its balance of qualities, one of the reasons it has found favor worldwide to the extent of seeming “universal.”

Western music surely projects qualities and ideals inherent in our civilization, including the assimilation of elements from various parts of the world. But above and beyond this, it expresses qualities inherent in life itself, in the human organism and human psyche. Classical music expresses all the aspects of the human: the physical, the emotional, the rational; earthly stress and heavenly calm; measured time and boundless eternity. In it we hear nothing less than the human soul reflected through the medium of sound.