The Essence of Technology

“Men first sense what is necessary; then they attend to what is useful; afterwards, they notice what is comfortable; further on, they take delight in pleasure; thereafter, they dissolve themselves in luxury; and finally they go mad in squandering their substances.” – Giambattista Vico

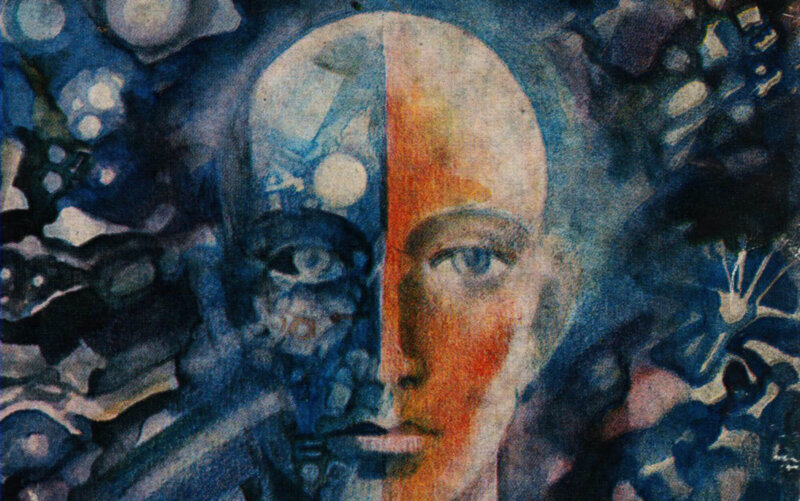

In our technological era we are raised to believe that technology is a mere tool that we can make good or ill use of depending on our “subjective” disposition. Technology stands for a value-neutral or value-free “object” ready-at-hand. Yet, as Martin Heidegger reminds us, technology is never innocent; for prior to appearing to us as a mere “object,” technology is inherent in, even constitutional of a mode of perception. This “mode” that, in the wake of Nietzsche, Heidegger decries fatalistically as expression of a cosmic Will to Power, is evidently characterized by a drive to grasp, to acquire indefinitely.[1] Technological man abides in a compulsion to appropriate what is not strictly his own (though it may be collectively available) by projecting his very life in an acquisitive project whereby the human “subject” fills itself, so to speak, with an “objective” world. This “filling” is achieved by what is conventionally called technology. The technological tool is then the repository of a project and is constituted with an end in sight, namely the overcoming of the modern/Cartesian conflict between subject and object. Now, this overcoming, as Hegel shows (anticipating Marx), unfolds in terms of a historical dialectic involving the self-negation of the subject in labor. Modern man works for an ideal, or its realization. What does it mean to realize an ideal? It means to convert nature-as-inert-material (a ready-at-hand res extensa) into a whole in which the human subject is fully at home. Now, we cannot be fully at home, or overcome our alienation from nature, without overcoming the threat of violent death. It is thereby the task of technology, or of the technological project, to overcome death in its raw state—death that is unmanaged or dangerous.

Admitting that death cannot be altogether eliminated, modern, technological man is projected into death’s own transposition into technological “ways and orders,” to echo Machiavelli’s formulation. Death is to be overcome through our self-negating labor as this contributes to establishing a world-order or “global system” in which death-qua-nature (the nature we ordinarily fallback or die into) enters as fuel. Now, death coincides here with all our “pasts” or “histories” channeled to converge into a single matrix, a total/global History in which death is “normalized” in the respect that it converts as inert material—death as graspable flesh—into self-reproducing machines. These machines constitute overall a world in which our death as problem is overcome and converted into death as commodity integrated into a technological world-order.

Considered on an individual basis, death coincides with “my body.” Human subjectivity tends to be identified today as a body (flesh) fueling a technological system of life, a system in which life is fueled by death insofar as the body is invested in labor serving the rise of a mechanical haven providing safety for all bodies. But now, how more precisely is labor to be understood here? Labor is articulated in terms of the self-negation of the body in the service of a machine feeding the body its technologically mediated forms of subsistence. The body is to be filled with technologically mediated or formatted material (most notably ordinarily ingested food/drugs and audio-visual recordings) binding the body to the machine until the body identifies itself entirely with the machine supporting it. Terminally, the whole of our human experience comes to be defined by a totalistic machine and its mechanical/compulsive mode of integration. We are seduced or flattered into grasping “pre-digested” material ready for immediate consumption/satisfaction making all effort, indeed all interpretative reflection, altogether expendable. Why, thought itself emerges at best as a commodity fully integrated into or mediated by the technological System, unless thought exceeds the demands of the System, in which case thought may be detected (by inference based on analysis of inordinate behavior) as a “public enemy” to be excised or “cancelled” at once.

The process of filling bodies with technologically produced satisfaction coincides with the process of driving consciousness to project itself in the technological System in terms of data. Accordingly, we are raised today to see ourselves as data that is best secured by being integrated in a digital network. The notion that our experiences can be collectively stocked and re-elaborated by an Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) is by no means marginal to the way children are raised today. Schools themselves have by and large driven our children to rely evermore on technological tools as models for shaping behavioral habits. As a result, youth tend to behave ostensibly more and more mechanically, even as human nature resists in the mode of behavior perceived as inadequate, deficient, dysfunctional, or betraying in all likelihood “mental illness.”

The importance of “mental illness” in contemporary discourse can hardly be overestimated, for under its banner the System justifies itself and its failure to provide universal satisfaction to all. Only the mentally fit or normal can be satisfied by the System; all others must be suffering from some mental disorder or another, thereby requiring “special (re)education,” which is likely to include indoctrination into the urgent need for everyone to rely on the logic of technocracy and the drugs it systematically prescribes (the contemporary pandemic of opioids and government sanctioned “medicinal marijuana” is indicative). Most importantly, our lives are to be cut off from any opening to questions exposing the roots of the technocratic regime and its dialectical unfolding. In this respect, the primary drug to be inculcated is “distractions” propagated mass-mediatically by an Entertainment Business.

In sum, the technocratic System delivers us the means by which it imprisons us body and soul, or until we come to identify ourselves as technologically mediated data, as we see in the case of the rise of an industry of sexual transformations. For trans-sexuality is justified on the basis of gender-identification/attribution established in the context of technocracy:[2] once our physical identity is defined in strictly mechanical-evolutionary terms, technocracy steps in to manage it in terms of symbolic forms such as “gender” that we are supposed to be able to choose freely. Here, gender is none other than a “subjective” correlative of an “objective” sex that is, however, fully managed by technocracy. We can speak of gender to mean at once sex insofar as the biological datum enters into a technological world in which we can speak of the biological in “subjective” (cultural, social, historical, etc.) terms.

In a world in which the reason of a governing regime (reason of State) posits itself and is generally accepted as having fully integrated the reason of bodies (natural reason), our self-perceived identity is not formally defined by either Nature or God, but by our regime, even as this invites us to “choose” our identity in a marketplace of alternatives defined strictly by the regime itself. Questioning the regime by appealing to either Nature or God, is no longer an admissible option. For both Nature and God have been pre-defined in mechanistic terms as “choices” secured in and by a technocratic marketplace. To step outside of that marketplace, if only in thought, will be highly and unduly subversive; as a troubling sign of lack of virtue, of impiety, or even, to speak with Kant, of “radical evil.”

If we are to survive, today, we are to survive—so we are raised to believe—in the Machine that will take charge of our very memories by integrating our natural imagination into the “clouds” of A.I. What we remember will be based on the stock of clusters of data provided by the Machine, until our natural impulse to recollect will be smothered beneath the weight of a compulsive curiosity under the sway of “trends” defined by algorithms integral to A.I.’s management of world populations (“chaos management”). Driven by “controlled curiosity,” we quickly lose desire to remember and thereby, too, to recollect? Why remember what A.I. has already secured for us into a universal System? What sense is there to remembering as long as we abide in a world in which A.I. defines at every moment what we should imagine and what we should not, and so what memory should surface and which one should not. Being fed A.I. stored “memories” based on present trends would seem eminently practical or efficient as opposed to remembering on our own. Why heed what we remember naturally when the System is fit to define what we should focus on and what we should deem irrelevant?

The A.I. management of imagination emerges today as key to the success of technocracy. Once our imagination is fully managed, so that the Machine will feed us our every memory and dream in a stream of compulsions, we shall no longer recognize any sign of a truth to be recollected beyond any reason of State, no matter how global or totalizing. Natural reason as our inalienable effort to recollect (as Plato’s anamnesis) will be forfeited, and therewith our own original humanity, as irrelevant and even toxic given that our machine-induced memories will lead us back into the Machine, binding us to a steady flow of “information” beyond which must lie—so we are induced to suspect—unnamable perdition.

Once fully integrated into technocracy, we will be inevitably faced with the prospect that the Machine will outlast us, as a God outlasts his creatures. Yet, where the logic of technology aims at total integration of the human in technocracy, once this goal is achieved, there would seem to be no reason for the production of technological tools not to come to a halt. If technology expresses modern man’s project to escape violent death, once the vast majority of men is fully integrated in technocracy—whereby our life-experience is overall mediated/shaped by and reliant upon technology (both as tool and way of life)—what ulterior end would technology advance towards? Once fully integrated into technocracy, we would stop laboring to enter into it; rather we would remain completely reliant upon the Machine as our autonomous guarantor of “free salvation” or grace. Would the Machine thereupon sustain itself? Would it labor to preserve itself, thereby reflecting modern man’s impulse? Would an autonomous technocratic regime carry on man’s quest in the absence of any human need and so even in the absence of man himself?

Once man’s memory is “saved” in an A.I. structure, man can linger at best as consumer of dreams spun by A.I. on its “Tower of Babel.” Thereupon, will the Matrix still stand to support men turned into dreaming larvae? We are inclined to believe it would, as long we remain under the spell of technology, viewing it as a mere tool. Yet, as we begin viewing technology in its essence, it becomes clear that technology must orbit around its original function as “historical synthesis” of subject and object. At the end of its History, technology, which includes both its proper function and its tangible manifestation, loses the former and therewith the latter. Yet, could we not (re)program the Machine to support us once we ceased laboring for it? Could historical technology not usher into a post-historical, post-dialectical technology as repository of life beyond man?

In speaking of a post-historical technology, we must have in mind the notion of technological tools used to fuel a post-technological, transhumanist cause. The new “technology” would cease functioning the way it had done “historically,” or to save men from violent death, and begin containing them if only by threatening them of and away from violent death. The production of tools would no longer serve mere entertainment, which aims at coercing people to forget their proper ends. Once our proper ends have been effectively obscured, entertainment is no longer needed and indeed people remain utterly insensitive to it, seeking a more radical, compelling alternative to natural ends in collective suicide. Herein can we discern the cause of a transhumanist post-historical “technology” (if of technology we still wish to speak): as the production of tools wanes, existing tools begin being used progressively as means to bring about suicide on a global scale. A.I. inherits this “esoteric” nihilistic order hidden at the heart of modernity’s “exoteric” promises. Once modern man saves himself technologically, his majestic scaffolding begins falling back on him to achieve what self-saved man compels himself to achieve in his final hour. For, not altogether unlike the antiheroes of Dostoyevsky’s tragedies, at the end of the rapids of history, we seek no mere survival—for survival has become unbearable to us—but safety in the great falls of a global conflagration. “And finally they go mad.”