The God of Philosophy or the God of Faith?

A wise man has written a book called God or Nothing—the title a profoundly pithy expression of the primary choice we must make in our lives. Yet in making that choice, we must be clear about what we believe and say about God. Various kinds of purely philosophical theism, not rooted in faith, have arisen throughout the history of Western thought and should be carefully pondered.

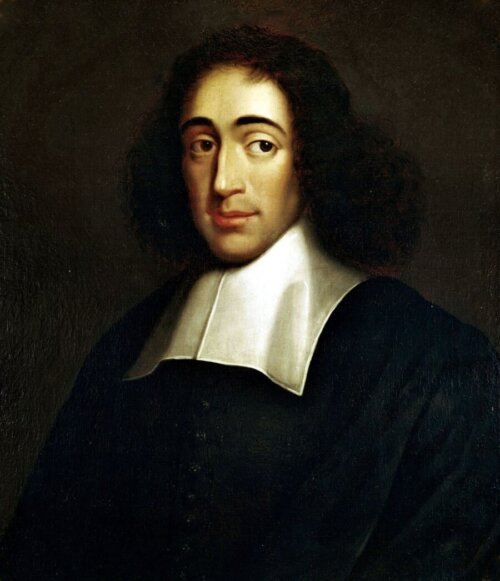

I am thinking of systems like the one propounded by the Dutch philosopher Benedict Spinoza in the 17th century. Spinoza’s beliefs were so novel, and went so much against the received wisdom of the Judeo-Christian tradition, that he was frequently declared an atheist. This is simply because his conception of God, which he outlined in his magnum opus Ethics, was so widely at odds with what Jews and Christians say about God that in the context of the time it seemed practically like no God at all. Spinoza, like such other thinkers as René Descartes, was part of the early wave of rationalism in Western thought, at the dawn of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. Those who did not consider Spinoza an atheist called him a pantheist—one who believes that God is somehow in all things. What Spinoza himself would have owned is the belief that Nature is, ultimately, all there is. Everything that happens, happens according to natural laws. God himself—and Spinoza makes it very clear that there is a God, to the extent that later commentators dubbed him “God-obsessed”—is the embodiment of these natural laws.

The all-embracing quality of nature and natural causes, for Spinoza, means that everything that is, is necessary. Things could not be otherwise than they are. But this is ultimately rooted in the nature of God himself. He is the perfect, all-powerful Being who is the cause of his own existence (here Spinoza honors Aquinas’ concept of God as esse subsistens) and causes all other things to be. Causes, note, not creates. The world came about through natural processes, not a decision of the will.

Indeed, Spinoza rejects both the idea of creation and the idea of contingency. God did not create, and to say so is merely to project human qualities onto God. Rather, everything flows necessarily from God as the necessary and transcendent Being. If one is beginning to sense that Spinoza sees God as an abstract force of nature rather than a person, one would be right.

These two ideas, it would seem, constitute the core of Spinoza’s challenge to traditional Judeo-Christian thought. For believers say that reality is contingent—everything that happens relies on a cause or ground for its existence, which could have been otherwise—and this chain of causes or grounds leads back to God, who created all things through a conscious act of his divine will. Also, they say that God is Person, the prototype for personhood as we experience it. The idea that God is First Cause but not in any way a personal being—because to say so is merely to anthropomorphize God—is thus a claim that cuts to the very heart of our theology.

The consequences of this philosophical theism are many. A universe in which everything is what it is by nature and could not possibly have been otherwise is a static universe. One’s reaction to it can be nothing other than a stoic acceptance and detachment, because the actions of us mere mortals cannot possibly affect anything. Hence, life in such a universe would seem, by our lights, to be a life without drama or nobility. Virtue such as we conceive it cedes way to rational understanding of the inevitable workings of nature.

Spinoza frequently presents himself in the Ethics as the doctor of our soul, curing our anxieties and delusions. He is engaged in a program of demystification. When he does take a break from the rigid geometric method of axioms and deductions in which his book is cast, he is given to digressions on how happy we would all be if we threw off our “superstitions” (like the quaint belief that God actually does anything) and became enlightened, rationalistic philosophers like himself. Then, presumably, we would all sit in our armchairs with the perfect knowledge that all things are necessary and preordained, undisturbed by regrets of what might have been or thoughts of how we could better carry out the will of God. God isn’t pleased by anything we do and is incapable of loving anyone; to say that he did would be to imply that he lacks some perfection.

Instead, what characterizes God above all is Thought. Spinoza calls God “a thinking thing,” who in a sense thinks all things into existence. Our own thought processes share in God’s thought, are to some degree God thinking through us. One thing that God is certainly not, in Spinoza’s system, is Love. This is because Spinoza classifies love as a passion, and God as pure Act (Spinoza echoes Aquinas again) cannot have anything passive in him. So, while we can love God—with an “intellectual love,” Spinoza specifies—we should not expect him to love us in return, nor should we expect him to reward us for our good deeds.

Again, Spinoza concedes that God is free and nondependent, existing from the necessity of his nature alone; but the effects God produces follow necessarily from his nature. One of the consequences of this is that man’s will is determined by the will of God. We only imagine that we have free will, but this is a delusion. We do not possess absolute freedom allowing us to choose how to act; rather, our actions are determined by our affects, which are determined by nature, which is determined by God. Spinoza’s is a tightly closed universe, where nothing unexpected or miraculous will ever happen—such as, one would presume, the possibility of God entering human history.

There is thus no mystery in the universe, and nothing supernatural (“above nature”). Things that seem mysterious to us are merely the result of a lack of knowledge (ignorance), which can be dispelled by applying rational thought. In Spinoza’s system we end our journey, not on our knees in reverence, but in the philosopher’s armchair in serene meditation.

Spinoza has appeared to build upon the edifice of the ancients and the medieval scholastics, but he has actually taken the floor out from under us, so that “God” and “man” no longer mean quite what they did. Yet there is wide latitude for disagreement here, despite the philosopher’s conviction that his ideas are logically deduced. A person of orthodox views who reads Spinoza may eventually reach the conclusion, not that Spinoza has proved that God is exactly as he describes, but that the real God—the God of Abraham, Moses, and Christ—is too large to fit inside Spinoza’s brain.

Spinoza’s is, after all, only one philosophical account of what God is. Philosophers, using the tools of philosophy, can surely reach other conclusions. They might even conclude that God is what orthodox faith says he is. For example, if we count personhood as one of the perfections that human beings enjoy, and God embodies all perfections, then he must also, in an even more preeminent sense than us, be a Person. Personhood must have its very origin in him. From this it must follow that God is also Love—i.e., love is his preeminent activity. Here we may answer Spinoza’s argument that love is a passion by conceiving it instead as an act of the will. God, as pure Act, acts out of love. Thus, Thought is not the bedrock principle in the universe; it is Love that “moves the sun and the other stars.”

Moreover, if we put abstract theories about determinism aside and think about our experience of life, we must admit how prominent contingency and serendipity are in the things that happen to us.

The choice, then, is not only God vs. Nothing; one must also choose between different visions of God. One of these possible choices is between the rationalistic God (which the believer would regard as a counterfeit, or at best only expressing partial truths about God) and the God of faith. One could make a case that only faith and religious practice foster and sustain belief in God at all, and that rationalistic theology eventually collapses or slides into atheism. The historical evidence might seem to suggest that. Then again, philosophical arguments appeal to only a small portion of humanity to begin with, and most people will need a revealed theology to capture their belief and allegiance. None of this of course proves which side is actually true. For that you need arguments, and that is why the believer can only benefit, intellectually, from familiarizing himself with the God of a Spinoza. Next to this reduced vision of God, the vision of God that faith proposes is apt to shine with greater clarity.