The Poetic Interiority of Sensuality

Quali fioretti dal notturno gelo

chinati e chiusi, poi che ’l sol li ’mbianca

si drizzan tutti aperti in loro stelo

As gentle flowers, by the frost of night

bowing and closed, upon the sun’s illumination

rise all open over their stem

(Dante, Inferno, Canto 2.127-129)

Our modern, mechanistic upbringing cripples us in our appreciation of what moves us. The nearly ubiquitously imparted notion that we amount to bundles of feelings moved by the mechanisms studied by “science,” perverts us away from a “pre-scientific” exploration of the problems underlying our physical reactions. What is the nature of the stimuli that prompt us to move every day—to awaken in the morning, to seek nourishment, to abandon ourselves to sleep? Why do we daily seek satisfaction, or pleasure?

As long as we accept slavishly the mechanistic dogma of the modern world, we fail to discern the real problems the modern “machine” was first established to eclipse, if only tacitly in the name of the construction of a New World, a laboratory-world in which everything is expected to be controlled as quantifiable, fit into an ineluctable grid of rules and regulations, of demands and expectations that no one and nothing is to bring into radical question.

Our modern shackles restrain us only as long as we do not let go of them by exposing ourselves to an order of things that, in cutting through the modern grid of mechanistic imperatives, promises to host us without trapping us, to secure us without enslaving us, to enlighten us without blinding us. Thereupon, we acquire new eyes, or we rediscover old ones allowing us to live without being lived, to move without being moved, to hope without being disappointed, to trust without being fooled.

The various facets of our daily experience emerge in a new, forgotten light, a light that brings back to mind, a light of recollection that awakens, not to dreams within further dreams, but to a permanence underlying all dreams: the moral-poetic meaning of all of our physical predicaments. So that our decaying bodies emerge as shadows of their poetic interiority, just as poetry emerges as the exploration of the meaning of all that is physical—the exploration of poetry’s own world as the realm of the meaning or true interiority of our bodily existence.

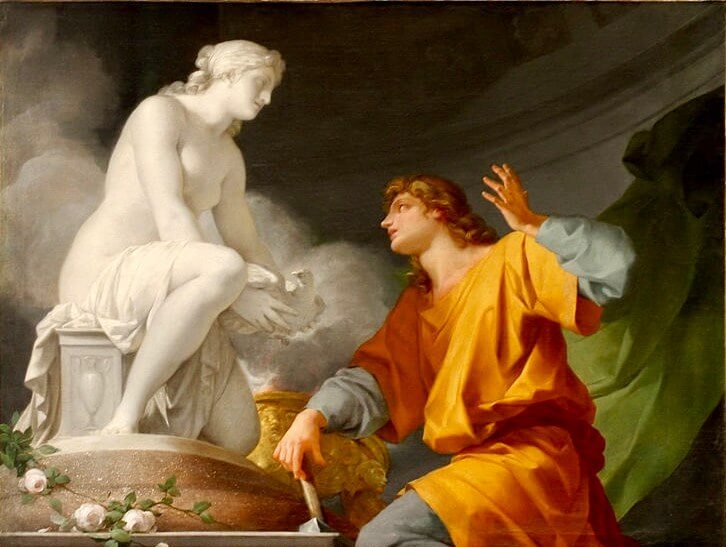

In exploring the interiority of our everyday life experience, poetry is responding to it: the heart of things calls or inspires the poet back to itself. Poetically speaking, the poet is Orpheus descending into the internal depths of life to save the surface of things by inviting its feminine beauty (Muse) to resurface and with her the light she bears. The poet’s consummate challenge is to descend into what is hidden, so as to draw it to illuminate what is manifest-in-disappearing, namely our dying bodies.

In terms of decaying, of dying bodies, the poetic quest is represented most intensely by sexual intercourse, which, properly or poetically understood, involves the meeting of male and female: in sexual intercourse, the male partner attempts to domesticate alterity, asking the female to trust his calling, to give herself to her male entreater who is to enter into the female to rescue life from within her. The male Orpheus penetrates the female to draw life from within her bosom into the light of day, of a world in which a new being, a new light ray, a new verse (as Dante’s fioretto) may bear witness to the meaning of all things.

“Bearing witness” is key to all sensual encounters, as to all loving relationships. Here, the female’s role is naturally complementary to the male’s own: in the former’s calling we find a search for relief on behalf of life itself, of an intimate secret begging to be set free. The secret that the immaculate female enshrines is none other than the light of all prophecy, “the light of the world” (τὸ φῶς τοῦ κόσμου; John 8.12) that is naturally prone to bear witness to, nay to incarnate its divine or transcendent source. Upon her trusting the male hero, the female heroically surrenders to the male entrance into the shrine of light. Here, the male is faced with a life-or-death challenge: he may guide the light “out” for its own sake, or he may surrender himself to it even as it remains buried in the female’s “earthly” or “infernal” bosom. Naturally, the Orphic character of the male is manifest in abstention from any surrender, even independently of the effect of his effort on the female and on the divine promise she preserves. Conversely, the female will fulfill her proper function only insofar as she does not abandon or betray, nay abort, the light that moves her to trust the male to begin with. No sooner has the female placed her trust in any end other than the light of her bosom and by extension in the male hero who is called to liberate that light for our world than she falls into alienation, radical dissatisfaction, if only in the act of grasping the ephemeral mirage of worldly satisfaction. Thereupon, all is emptied of meaning, cynicism and dread ensue, followed by hateful resentment and a sense of devastation in the face of a fall from what was originally meant to be—from the female’s divine mandate.

The example of Judas Iscariot’s “selling” of Christ is instructive, here, insofar as it bespeaks not only the betrayal of the consummate Prophet, but also that of the womb that bears him. Having come face to face with the unbearable vision of his betrayal, Judas rejects both 1. the silver coins awarded as prize for the betrayal of truth and 2. his on life. For there can be no life without truth. Or more precisely, life without truth is not worth living; life that is not illuminated from within by truth remains stained. Unavoidably, the betrayal of Christ entails the rejection of his immaculate conception. No mask that money can buy could ever save life from the stain of blood Judas condemns himself to the very moment he trades truth for money as universal mask. The monetary mask Judas is given in exchange for truth cannot but stain the traitor’s life unto death.

The Gospels’ lesson is glaring: the betrayal of truth (its trade-off for masks) calls forth by necessity the abandonment of life—fall into oblivion. In the absence of truth, life is unredeemable. No number of masks can conceal the loss of our original face; the void (the price paid for abandoning truth), the lie the masks attempt to distract us from, cannot but expose our masks as funerary, masks revealing our own suicidal betrayal of life, of a life that gives itself from within, not for the sake of recognition (its poverty points to solitude in hiding), but for the sake of recognizing, or naming those who are “elected” by God.

Christ on the cross is univocally giving himself without or beyond any recognition. In its essence, the moment of death is never for itself, reminding us that all sensual life, including sexual encounters, transcends any need for recognition. The end is not self-satisfaction. On the contrary, as death, our ordinary sense experience requires self-sacrifice, or the letting go of oneself. In dramatic anticipation of death, sexual intercourse is especially incisive in reminding us of the need to let go, to enter into the domain of an impersonal mystery (not to be mistaken for the impersonal absurdity of modern machines). On the other hand, sexual intercourse calls into question mutuality. What is to be sacrificed is no modern, chimeric “individual,” but the inter-personal life as a whole, beginning from the person as inevitably bound to other persons, the person as representation of the ethical domain. In sexual intercourse, ethical life itself, including any demand for collaboration, is sacrificed and this is achieved inter-personally. With the male-female mutual consent, the whole moral universe is exposed to its metaphysical foundation as physical appearances convert to their poetic interiority. Thus does the sexual encounter anticipate the restoration of the poetic life, where ethics is no longer chained to the corruption of everyday life, a corruption entailing thirst for closure onto finitude (whence the rise of demands for recognition). Unfettered ethics binds itself to its own hidden treasures, (re)converting into (and rediscovering itself as) the quest for the sacred, a quest we are destined for as human beings.

The sexual encounter stands as a door of awakening to the original destiny of man, an ethical destiny pointing to the birth of light in the midst of all ethical corruption. In sexual intercourse we open ourselves to the promise of genuine, religious redemption, of a return to the original covenant between human, political–moral life and its metaphysical “after-life”. The promise, on the other hand, points back to a thought that alone fulfills the promise, not by transporting the metaphysical onto the plane of ethics, or by “creating Heaven on Earth,” but by retracing the “after-life” to a “before-life”—the religious promise to its own mysterious origin.

Nothing is more alien to our origin than the unquestioned sensual life, the sensual shut within itself. When ill-experienced, sexual intercourse serves as turbid coverup for problems we fear insofar as we have abandoned them on the way to reifying them in physical terms. Here, the physical body (physical motion) is the imposture of a moral body, of poetry’s own movement. Those engaging in sexual intercourse on primarily physical terms, as if the body were its own ground unfettered by any moral consideration, have betrayed the poetic challenge that sexual intercourse is but a shadow of, in favor of using sexual intercourse as a means to self-empowerment, to self-satisfaction, to closure to the living nexus between ethics and metaphysics, between the human and the divine. No longer experienced as mere shadow of a poetic challenge, the sexual is now narcissistically conceived as absorbing the divine within itself.

Poetry as conversation open to eternity comes providentially to the rescue, responding to the collapse of life into sensory impulses by entering into the very midst of sensual turmoil to restore it to harmony, the harmony that is none other than poetry itself. What we learn from poetry’s arrival on the scene of sexual intercourse is that the sensual is a shadow, not of an eternity it may then absorb within itself, but of poetry; that bodily movement, including the most tumultuous, is nothing but the shadow of a moral movement, of the soul’s response to the permanent problems constituting the soul’s own divine foundation. There is a story unfolding in sexual encounters, a conversation open to its metaphysical foundation. That story, that conversation, that poetic challenge constitutes the heart of all moral life, the place where morality emerges in the light of divine transcendence. To repress that conversation, if only under the pretext that its sensual shadow is likely to lead people dangerously astray from both ordinary moral life and its sacred principles, is to fall prey to the temptation of the bigot to mistake safety for virtue and conformity for truth.

Poetry vindicates the danger of the sensual life by restoring that life to its original moral significance, in the context of a story binding the ethical to the theological, our ordinary life to a mystery beyond our grasps. Where the respective roles of lovers are engaged in poetically, physical time tends to vanish and the earthly is no longer sensed as support (“we are swept off our feet”) as the loving couple gives itself to a silent dialogue exposing our life to its mysterious source. Ordinary life is thereby “reset,” as on the “first day of creation” that Solzhenitsyn evoked so candidly in the closing pages of his Cancer Ward (1968).

Naturally, the misopoetic soul knows nothing about what is morally pristine; on account of that soul, sensual satisfaction marks the violent death of all poetic aspirations, signaling the absurdity of any return to purity—so that all sensuality must be stained and its stain must warn us that life is but empowerment, that there is no truth beyond the grasps of the Philistine, no innocence in danger, but cunning and calculation; no friendship in sensual encounters, but strife and one-upmanship: the struggle to overtake, lest one be overtaken; to master, lest one be mastered; and, to speak most bluntly, even to kill, lest one be killed; to efface “the other” lest he or she efface you.

How cynical this poison of crude rejection of poetry; what blinders it raises over our feeble eyes! It breeds resentment by shutting all doors to the understanding of what escapes our libido dominandi, our compulsion to grasp, to control, to dominate, to trade domination for care. The loved one is “exposed” as the object of hate; love is exposed as a mere pretense soon to be crushed under the weight of the demands of self-assertion, of recognition, of a soul dreadfully frozen in earthly determination. The Mutual despised in favor of the Univocal, conversation implodes into the monotone rant of “the individual” haplessly torn to shreds, however, by the senseless existence he swears by. There, the betrayal of poetry spells out its last, fatal word: nonsense.

It is against all nonsense, all nonsensical sensuality, that poetry knocks at our door, the door of lovers, to call us back to an innocence banished on scientific grounds by our technological societies. All “scientific grounds” are shattered by poetry’s “pre-scientific” call, allowing us once again to face the challenge of love without mistaking it for the temptation of death, of “loss of power”. Naiveté is restored and the possibility of meaningful mutual giving is reintroduced at the heart of our everyday life-experience. The most dangerous sensual encounter no longer smears innocence, but draws it, as it does our everyday morality to a beauty that seeks no earthly satisfaction, but that—as Botticelli’s Chloris (in the painting known as “Primavera”)—yearns gracefully for blossoming, metamorphizing spontaneously into Flora, incarnation of the poetic virtue (virtus poetica) constituting the salt of true human life.

In turning its back to nature’s poetic inclinations, moderns has sought refuge in projecting themselves into the sub-human embellished by tentative moral precepts purported—yet failing—to fill the void left by the abandonment of traditional moral life. Our minima moralia (Theodor Adorno) are not going to suffice to “justify” our survival; our lessening of pain is not going to make it worthwhile “ensuring life,” a life that remains an unbearable burden for us and our “minimalist ethics,” our pragmatically cherished “weak thought” (Gianni Vattimo). So we condemn ourselves to masking the burden we are born with, denying the dignity of our very birth by retracing ourselves entirely to the sub-human, that which is devoid of proper dignity, unworthy of honors, unqualified to serve as moral example. Ethics survives—and with it, our various arts—as consolation in the midst of a horror story we embrace as common destiny.

The horrific upshot of modern progressivism is not averted, but confirmed by the neo-Romantic retreat of man into moral mediocrity. Both modern optimism and modern pessimism hold fast to the Machiavellian assumption that we exist in a violent world, that violence is a necessary condition for our everyday conduct, that we must do violence to ourselves in order to “survive”—that to “thrive” in our world is to overcome violence through violence, above all by doing violence to our own nature, by confining our own nature within the strictures of a strategy or “war-plan” allowing us to win, to overpower alterity in the supposed “jungle” of life. Any old ethics open to transcendence appears as counterproductive, as ineffective, as leading to failure; only the new ethics of success is recognized as valid and legitimate, for the new Machiavellian ethics faces problems in the here and now—hic et nunc—without being distracted by “otherworldly” considerations, considerations pertaining to a world beyond violence. It is precisely closure to “the beyond” that allows the new ethics to acquire its prestige, to attract, nay produce, the esteem of the crowds of its sustainers. The new ethics, the new plan, engenders its own world, fulfilling its own prophecy replete with its massified disciples. The rise of the Plan, the Great Project of modernity, carries within itself the rise of masses of believers whose sole purpose is to serve the Plan as an unquestionable destiny.

It is in this context that the classical poetic redemption of the senses cannot but be condemned, not merely as Savonarola would have condemned Botticelli and thus in the name of a divinity that has no time for gentle education, but in the name of a violent existence that waits for no redemption, be it poetic or despotically theocratic, because now violence is its own solution. For where life is grounded in violence, it is only by doing violence to ourselves that we can live fully. Whence modern’s man visceral frustration. In the modern world we are supposed to be constitutionally frustrated, prone to anxiety, tempted to betray the demands of our Open Society, if only by dreaming of a world immune to it, a Platonic mirage that our times have no patience for—that we can no longer tolerate. Accordingly, violent sensuality will be not only approved of, but ubiquitously promoted, while poetic sensuality will be at best ostracized, at worst condemned as alienating us from the real demands of life. For poetic sensuality opens the door to a redemption beyond violence, a redemption from our Open Society, a way out of the violent existential vortex that society upholds as our sole or consummate raison d’être.

The vision that, throughout antiquity and up to the modern age, had remained latent, regarded as a corruption, something shameful, is now the official mantra: life as violence and poetry as camouflaging the violence, if only under the pretext of consolation; poetry as make-up, some sweetness that children need in preparation for violence, a sweetness that allows them to live without being overexposed to violence. Thus do we feed children illusions, Santa Clauses easily managed by the marketplace, as baits leading children to become accustomed to the suspicion that life is fundamentally meaningless, that all promises are vain and that therefore the marketplace is our only salvation—money being the most universal mask of our fallenness. A vast panoply of idols, of as-if’s, comes to bespeak the “sacredness” of the mercantile funerary mask of a divine secret long discarded.

Classical antiquity rejects such views as horrible, in full awareness that for cynical people, including the sophistic interlocuters of Socrates—not least of them, Thrasymachus—all beauty, all innocence, all goodness is a lie, insofar as everything is (assumed to be) fundamentally strife, violence: a tenet that for centuries was held in popular contempt, as preposterously impious, just as in our age it has become officialized as the bedrock for all sociology and “political theory,” calling us to assume that it is sinful not to entertain the tenet with unquestioning devotion. Our allegiance is demanded even as the demanding lends itself to be doubted, to be discerned in the light of classical warnings—warnings that, where carefully attended to, show us that what in ages bygone amounted to nothing more than private suspicions has been unjustly and unjustifiably raised, today, to the status of public certainty.