The Sorcerer’s Apprentices: A Review of “Time of the Magicians” by Wolfram Eilenberger

“I am therefore of the opinion that the problems have in essentials been finally solved. And if I am not mistaken in this, then the value of this work secondly consists in showing how little has been done when this problem has been solved.”

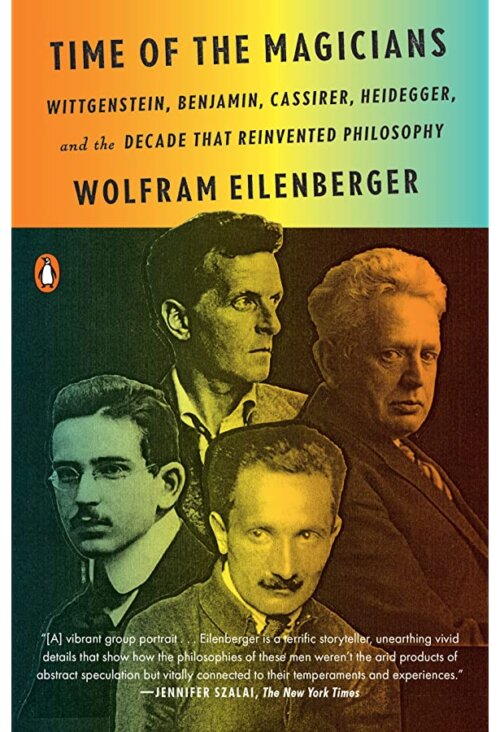

Wolfram Eilenberger. Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade that Reinvented Philosophy. New York: Penguin, 2020.