What Constitutes “Genius”? Beyond IQ and the Importance of Creative Individualism

What constitutes genius? Who is a genius? The Genius Famine, by Bruce Charlton and Edward Dutton, answered many burning questions that have arisen for me over the course of several decades that have importance for the notion of genius and what constitutes a genius and why we still need geniuses:

- The populations of Japan and China score higher than almost all Western countries on psychometric tests, so why have there been so few “geniuses” produced by these countries? Is “genius” a Eurocentric concept?

- As a corollary of that, why do the Chinese just copy American technology through reverse engineering and industrial espionage instead of creating their own? Yes, it is easier, but also derivative and destines them for second rate status.

- Why would someone who came top of his class in English, second to the top when transferred to an élite private school, find the vocabulary of Charles Dickens fairly challenging as an eighteen-year-old? (Names for Victorian ladies’ hats and kinds of wallpaper did not help.)

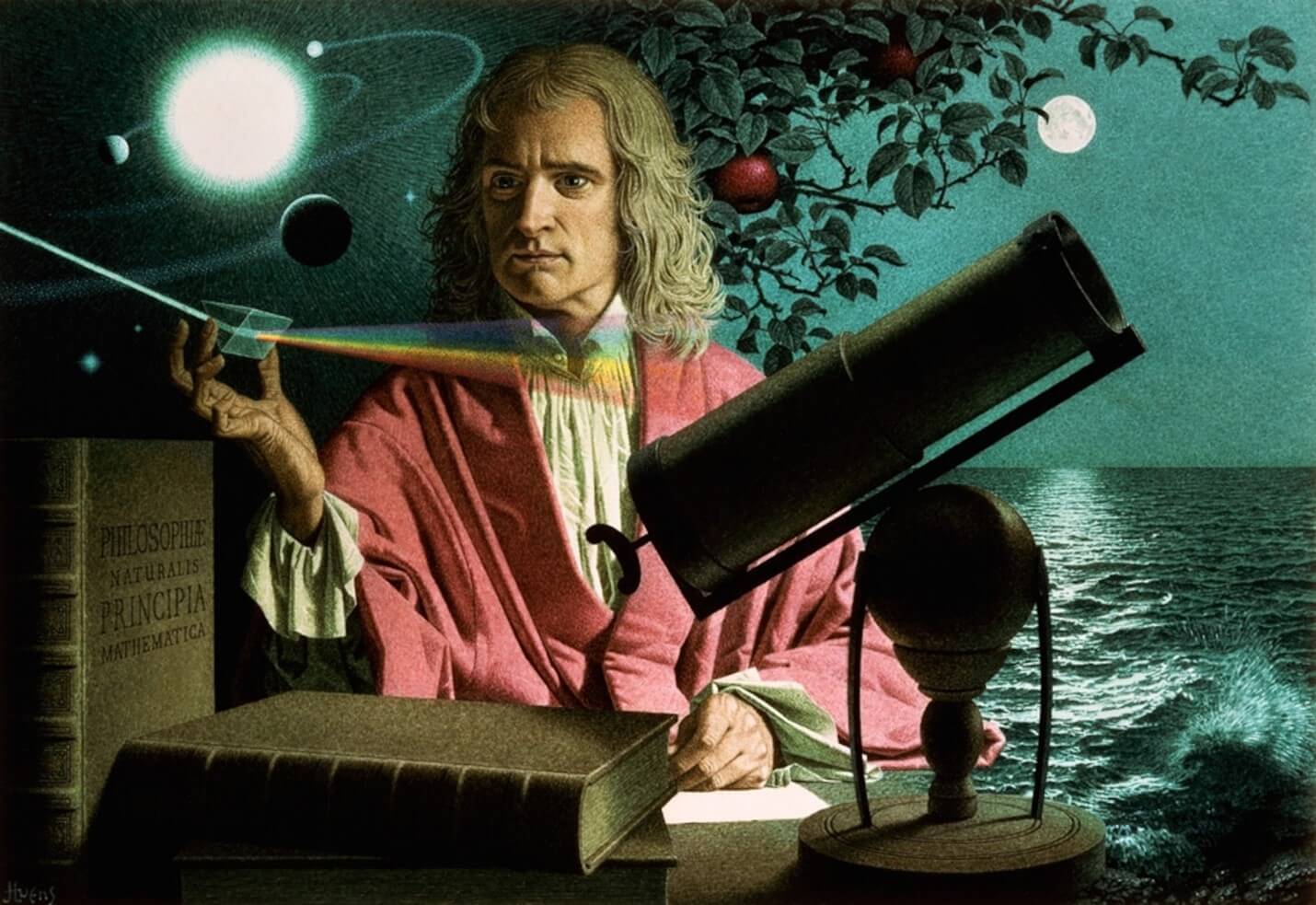

- Why are there no genius physicists at all anymore; the kind that make real, meaningful contributions to basic theoretical physics? Our “genius” physicists are now individuals with a lot of knowledge about physics but make no meaningful contributions to physics. We are still waiting for a grand unifying theory to reconcile quantum physics and relativity and a solution is nowhere in sight. In the first half of the twentieth century, we had unmistakable geniuses like Rutherford, Heisenberg, Schrodinger, Max Planck, and Einstein.

- Where are the genius musicians, poets, philosophers, painters, and novelists? The 1990s saw the mishmash recycling of styles of post-modernism, with seemingly nowhere to go, as though music and literature had exhausted themselves. We had the nihilistic geniuses of Joyce, Picasso, and Schoenberg, in the early twentieth century, all of whom, Dutton suggests, were artistic dead ends. Academics could not have boosted atonal music anymore if they had tried, and it is effectively dead. Though it is true that the past can seem disconcertingly intimidating because there has been a lot of time to accumulate a list of worthy geniuses. But it has been seventy years from 1950 to 2021. Think of what the physicists did in a mere 40, from 1900 to 1940.

- The late eighteenth and nineteenth century had Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mahler, Liszt, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Berlioz, Puccini, and Verdi. The twentieth century produced Stravinsky, Richard Strauss, and Schoenberg, and that’s about it. And most people do not even like the last one.

The answer to the first two questions is that the kind of genius that alters a culture and expands and enriches society and culture for evermore has been largely a product of Europe whether we like to admit it or not, though not in the way certain individuals and groups implicate and or in the manner that our so-called public intellectuals shriek in terror from when condemning the concept of the genius. The results of their genius, however, have created what we think of as the modern world, capable of supporting seven billion people, thanks to advances in roads, shipping, engines, planes, farming, medicine, fertilizers, and other technology. This generates a certain resentment from the beneficiaries, who it seems wish that it could have been they who produced these wonders. Geniuses need to have a high intelligence, of course, but they must also be endogenous – inner directed, creative, and intuitive. This is far more important and the defining characteristic of a genius and culture plays an undisputed role in shaping the inner directedness of individuals. Furthermore, they must have traits of psychopathy. They typically will ignore the usual quest for sex and social status – generally being celibate and almost never having children. They will instead dedicate themselves to a self-chosen obsession, approached using first principles, rather than reading other people extensively and applying the results of their research. They are antisocial, and do not care much about the thoughts, feelings, and opinions of others (low agreeableness). They are not conscientious and do not follow social norms and the expectations of others. The highly intelligent often lack common sense – so that popular trope of the absent-minded professor is true. In fact, they resemble idiot savants to a surprising degree.

Idiot savants have unusual abilities coupled with extreme deficiencies, though their talents are typically useless and they do not make major culture-altering contributions, unlike geniuses as they are defined here. They also need to be cared for by parental figures. It turns out that geniuses typically also need to be protected from the world and are frequently looked after by their families. Jane Austen, Emily Dickinson, Paul Dirac (almost never spoke), Wittgenstein (wouldn’t eat with colleagues, socialize, or do administration, taught what he wanted and only the students he liked), Blaise Pascal, Gregor Mendel (the discoverer of genes), Thomas Aquinas, Alan Turing, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, Fyodor Dostoevsky (gambling addict and not very competent in life) in other words, half the authors of the books on an educated person’s book shelf, were rather helpless and incapable and were looked after by their families, wives, for the very few that had one, and by monasteries that sheltered them. Einstein got lost near his home once and walked into a store and said “Hi. I’m Einstein. Could you help me find my way home please?” Gödel depended on his wife and would only eat her cooking. He literally starved to death when she was hospitalized. Paul Erdos slept on the couches of mathematics professors and collaborated on articles with them. A book has been written about him called, The Man Who Loved Only Numbers. Theirs is not the fake creativity of originality as novelty. As Charlton/Dutton point out, Constable and Gainsborough are less original, but are better painters than Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. (It is tempting to think that their famous last names helped their careers with the last two.)

High intelligence seems to develop in populations where farming is possible. Difficult climates, but not too difficult. The environmental aspect of intelligence is important, something hereditarians often ignore. But more than environment is the cult of creative individualism in the genius. East Asians come from an environment agreeable to agriculture and, as mentioned, are highly intelligent but are often too agreeable and conscientious to generate many geniuses unless they immigrate to more individualist societies. Traditional East Asian culture and society is extremely group focused, or collectivist. The amount of time and effort they put into “saving face” for others is quite exhausting. In Japan, workers are assigned a pod of other workers. If one person messes up, the rest are held responsible. They will typically only take half their vacation out of a feeling of responsibility for letting the group down, since they have to do their own work and part of their vacationing colleague’s work too. The genius is not concerned with the group, although his talents end up serving the group in all sorts of ways, including helping them compete with other groups. This is why East Asian immigrants seem to flourish and become geniuses when living in Western societies where they are freed from group consensus and embrace creative individualism.

European intelligence is believed to have reached its peak in about 1870 and has been declining ever since. It is estimated to have diminished by 1.5 points every decade so that we are down by 15 IQ points since 1900. The average academic will now be as smart as a high school teacher was in 1900 – though partly because of the proliferation of higher education institutions. Charles Dickens’ books were serialized in popular magazines. Ordinary people read them without difficulty. Now, if an “announcement” or quiz for students uses a word like “disparage,” or “mercenary,” used figuratively, they will not know it. All of them will not only not look the word up, but not think to do so.

The contrast with Dickens might make it seem that languages just get simpler over time. They do not. That is empirically false. Knowledge of difficult words is an indicator of high intelligence and our simpler vocabulary is indicative of our lower intelligence. Differential color perception and reaction times are also correlated with high IQ and both have gone down. Fast reaction times indicate health. Being a quick thinker means your brain is physiologically functioning well. There is no natural selection for stupidity. Stupidity is the result of mutational load – bad mutations accumulating leading to poorer brain function. In fact, all your organs are likely to be affected, so people will be of poorer health generally – prone to obesity (low impulse control also) and diabetes. High intelligence is associated with living longer because generally, smart people are healthier. Plus, the highly intelligent are future-oriented and can use their intelligence to control their instinctive impulses better. We are now only as smart as we were in 1600 and thus could never have generated the Industrial Revolution. Since the smarter control their impulses more, they are also more sexually repressed, leading to Shakespeare being bowdlerized in Victorian times. Our “sexual freedom” is also a sign of our declining intelligence. This aligns perfectly with Plato’s Phaedrus. There he describes the human soul as composed of a white and black horse and a charioteer. One horse pulls heavenward, towards Beauty, Truth, and Goodness – the heaven beyond heaven, and true reality. The other, back down to earth, and the satisfaction of bodily desires. Only he who manages to control the dark horse is fully human and gets to return as a human in the next life.

High intelligence and education are inversely correlated with having children, especially with women. So, the modern tendency to spend years in higher education well into the twenties, contributes to infertility among the smart. Then, the easy conditions created by English geniuses in the fields of agriculture and industry, leading to the Industrial Revolution, along with things like increased sanitation, meant that nearly all the children of the poor and unsuccessful, survived. Also, the poor could afford to have more children and to feed them. This can be contrasted with the Black Death that killed 80% of peasants, and the 2% of the population who were executed as punishment for not necessarily terribly serious crime every year in the Middle Ages. And criminality is associated with low intelligence, and poor character (high impulsivity, antisocial tendencies, etc.) During Medieval Europe, the poor died in childhood in huge numbers, the rich and successful survived, and through this dynamic and learning intelligence slowly increased. We then became a victim of our own success, stopping this rather brutal natural selection in favor of the smart, and the poor and less mentally and physically healthy had more babies than the obverse. This ramps up the mutational load with dysgenic effect. World War I further culled the smart people. Officers led from the front and were from the upper classes, the best and brightest, leaving a generation of women who refused to marry down, in the usual hypergamous manner, to live out their lives as spinsters.

As intelligence decreases, Dutton opines elsewhere, we can expect more accidents and failures; planes falling out of the sky, apartment buildings in Florida collapsing (which recently happened), software updates actually making things worse instead of better.

The other factor is that modern culture actively selects against genius and is hostile to it. The antisocial Wittgenstein who refused to do administrative work, and would only teach what he wanted to, would simply be fired. In fact, he would never have been hired in the first place. As people get less intelligent, we have to chop complex jobs up into simpler pieces. Thus, a bureaucracy is formed and new faculty are chosen by committee. Collegiality is a major requirement. They must have the right credentials. Geniuses are often so lopsided in their intelligence that they do not perform well academically. Newton barely got his BA and had to be asked his examination questions all over again to get him through, which was considered a major disgrace. This from a man with no formal training in mathematics. He was self-taught and within one year was as good as any mathematician on the planet and then went on to make his singular contributions. Applicants must have a willingness to follow social norms and bureaucratic requirements, and thus to exhibit high conscientiousness. An actual genius would be eliminated at the first opportunity. Even for people of normal academic intelligence (115 for an education professor and for a social scientist, 130 for physics, 129 for mathematics and philosophy, depending on how elite the institution is of course) scientists in particular must get a “grant.” In the grant, they must state what they expect to discover. They must fit a particular timetable. They must outline the steps they intend to take to achieve this goal, and so on. In other words, they must be dull and conscientious, kowtowing to group think and bureaucratic nonsense. It is understandable that those providing funds want some assurance that their money will be well spent, but to have to effectively state what you will discover before you discover it, and particularly to do it following a timetable, and then one with incremental, algorithmic steps, has nothing to do with the creativity and intuitiveness of the genius. In fact, it is not how discovery works, period.

Current academia is mired in extreme conformism and has a giant parasitic, vampiric leech of a bureaucracy sucking at its teat which inhibits individual genius to flourish despite the fact that many in academia are of high intelligence (comparatively speaking). HR has gone from four staff members to well over twenty in the space of a dozen years at one place I can think of. There are provosts, and deans, and then innumerable “assistant” deans, all with their own mini bureaucracies and staffs, who have to figure out new onerous regimes for faculty to undertake to justify their existence.

So, there are almost no geniuses due to active hostility to them, collectivist mentalities, indoctrination to conformity, and, of course, stagnating intelligence (by all empirical test measurements). Even very young people seem to realize that people are not as intelligent as other generations in the past. We have gone from farm laborers listening to five-hour complicated debates between politicians in the mid-nineteenth century America, to thirty second attack ads on TV in the recent past, to “students” with no interest in academic topics sitting in class fuming if they are not allowed to distract themselves online. Preliterate oral cultures were functional and focused on rote memorization and either learned what they needed to know, or died off. Literate cultures represented an enormous expansion of the human mind and liberated it from mere rote learning and permitted the possibility of critique. At certain points, it gave individuals access to the whole history of mostly Western thought to learn from. A post-literate “culture” may turn out to be an oxymoron. It has not gone through the trial by fire of oral cultures, and literate cultures. We blame functional illiteracy on “technology;” smartphone addiction and the like, but it might also be that dumb people are not as interested in abstract ideas.

It is tempting to look at painting and classical music and to say – “Well, they are simply played out. There is nothing more to say in those fields of artistic endeavor. What more could possibly be done?” But, it seems very likely that that is simply how things look to the non-genius. We are not tempted to say that there are no new discoveries to be made in mathematics, and everyone who has paid any attention at all knows that physics is hopelessly incomplete and has reached a temporary impasse. It is patently clear that some creative, intuitive genius operating on his own self-chosen first principles, with enough psychopathy to ignore received opinion and looking to others, who is directed inward on his quest to which he has dedicated himself, is needed to break through to an entirely new horizon of thought. Us mundane earthbound types simply cannot imagine what that will look like. It stands to reason, that we do not know what the next step in painting and classical music could look like. Interestingly, we are not similarly tempted to think that literature has reached its limit. To anyone tempted by the post-modern lack of creativity and recycling of the past to think we have reached the end of the line, think how people might have felt before Hesiod and Homer emerged, before Shakespeare turned up and transformed the English language as a simple byproduct of wanting to write entertaining plays. Before Cervantes invented nearly every “device” a po-mo novelist could use. No one could have predicted them, nor foreseen what majestic works of art they would create. It is unwise to imagine that any field of human scientific or artistic achievement has simply reached its limit. What makes physics so interesting is that the human race is holding its breath, awaiting the solution. Presumably, the actual answer would be so unexpected and transformative that, were we to find it, we would shake our heads to think how primitive we once were.

Dutton, in other writings and lectures, rejects the idea of “low hanging fruit.” This is the notion that some scientific discoveries are “easy,” just sitting there waiting for someone to notice them, and others take far more effort. Thus, because of low-hanging fruit, later inventions and discoveries are harder to make because they will be high hanging fruit, to coin a phrase. Does anyone think that classical mechanics with its calculus, or the theory of relativity, were “low-hanging fruit?” Some inventions, like wheels on suitcases, seem trite and obvious, but that is easy to say after the fact. How long did we have wheels and have suitcases before someone put them together? Apparently, it was not so low hanging after all. The Manhattan Project was not low hanging fruit, and neither was cracking the Enigma Machine code by Alan Turing.

The genius is inner directed. He follows his own interests independently of what others around him seem to be interested in. He obsesses over a subject and thinks upon it constantly. He is creative and intuitive. He has a vocation and self-directed purpose. Michael Ventris, the self-taught linguist who deciphered Linear B, the Bronze Age Mycenaean Greek script, visited a museum, aged fourteen, where the guide mentioned that Linear B had never been deciphered. He devoted himself to the task of deciphering it, succeeded, and died shortly afterwards. Mission complete. Some of us non-geniuses can feel some kinship with this aspect of genius with their low agreeableness and not wanting to join community organizations and the like. The genius, then, is also more than just high intelligence. The genius is a product of individualism that we should not want to lose. Otherwise, we may have an educated society without the creative genius and spirit to propel the next advance in human civilization. The end result will be a stagnated tyranny despite all the technologies and accessible materials around us. Don’t we sense this is happening right now? What good is high, or reasonable, intelligence without the creative liberty that the genius embodies and that we all benefit from?