What Did Saint Ignatius of Antioch Really Believe About the Eucharist?

It is commonplace, even among most non-Catholic Christians, to read Saint Ignatius as affirming “sacramental realism” in his writings. When I was at Yale, this was the view reinforced by our patristics professor, an Episcopal priest and scholar. After all, the language is very straightforward, isn’t it? Not exactly, Frederick Klawiter argues. Instead of sacramental realism, the “real” body and blood of Christ, Klawiter argues that Ignatius’s view of the eucharist was grounded in signification and was ultimately more about himself—linking the soon-to-be-martyr with the redemptive sacrifice of Christ on the cross, a eucharist signifying and uniting the Christian with Jesus’s own martyrdom.

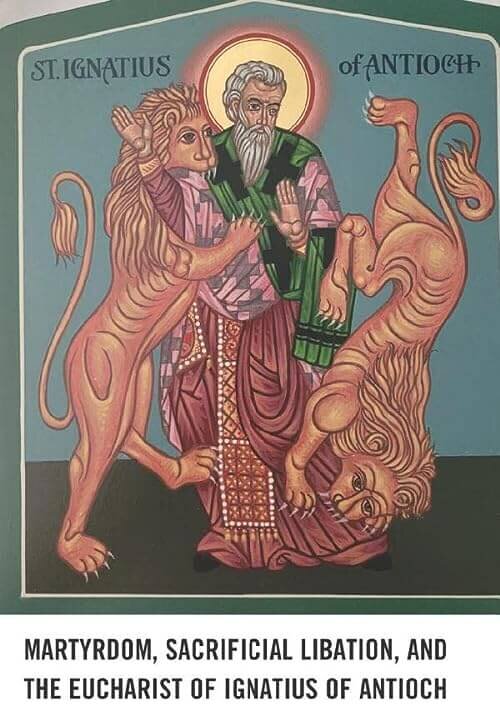

A few things about the earliest Christians seem perplexing to most Christians today. One is the centrality of the eucharist expressed in the letters and writings of the pre-Nicaean Fathers, Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp are among the favorites of the eucharistically-minded Christians to point to concerning the contemporary eucharist debates within Christianity. Another is the fervent desire for martyrdom among the early Christians. Many contemporary Christians have a vague awareness that the earliest followers of Christ died terrible deaths. Nearly all the Apostles were martyred. Stories of Christians being fed to the lions is still one of the images of early Christianity that pervades Christian consciousness despite the attempt of academics to downplay the scale of early Christian martyrdom (even though the literary evidence abundantly testifies that persecutions and martyrdoms were happening). While many Christians like to tell themselves that they’d die for Christ in the same way the earliest Christians did, the eagerness of early Christians to be killed strikes us as strangely weird. Ignatius of Antioch is also a prime example people point to for the early Christian belief in imitative martyrdom.

It is this crossroad of eucharist and martyrdom in Ignatius that causes Frederick Klawiter to reexamine the letters of the bishop of Antioch. Do his letters really entail, as the majority of scholars “[i]n the last century” assert, “that St. Ignatius’ understanding of the eucharist was sacramental realism”? Klawiter emphatically argues No!

One of the problems of biblical theology over the past century has been the infiltration of the Hellenist school, rooted in now discredited German scholarship of the late 1800s and early 1900s, which argued for the New Testament’s philosophic provenance. The New Testament writings couldn’t have been composed until after Greek influences were taken up by early Christian authors; this explains why there is some seemingly similar language between New Testament writings and Greek philosophy. The argument is well-known even if most contemporary scholars have moved beyond it. Klawiter thoroughly deconstructs and demolishes this lingering view, even if only indirectly, through showing how early Christian theological beliefs and practices were rooted in Jewish ideas (now widely accepted in mainstream biblical scholarship since the discoveries of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the scholarship of E.P. Sanders) like how “sacrificial libation completes the sacrifice of the lamb in the Tamid service.” Those who are influenced too much by a philosophical approach to the Bible rather than a late Second Temple theological approach, are guilty of perpetuating now discredited understandings. This reorientation to Jewish theology is important for Klawiter because in returning the focus of Ignatius back into a late first century Jewish context he can offer his novel argument against sacramental realism which implicitly depends on Greek philosophical argumentation.[1]

Instead of Ignatius’ letters articulating the widely accepted “real presence” (for lack of a better word) of Christ in the eucharist and libation offering, Klawiter emphasizes the early church reality of martyrdom as the key to understanding the letters to the Romans, Smyrnaeans, and Philadelphians: “Ignatius’ desire to appropriate the reality of the crucified-risen Jesus through his own sacrificial death is clearly expressed in the cultic language of eucharist/agape.” What follows is Klawiter’s reassessment of what really mattered to Ignatius and other early Christian writers (like Polycarp). To this end our author declares, “Ignatius can endure the suffering [of martyrdom] by sharing it with the Christ within, who sustain him. Martyrdom is a fellowship with Jesus Christ in the midst of a suffering like his.” So instead of a theology of sacramental realism, Ignatius’ writings “illuminate instead the reality of [his] martyrdom.” The focus, then, is actually on Ignatius rather than Christ, Christ serves to give Ignatius the strength and comfort to accept his impending martyrdom as an imitation of the Lord.

The great strength of Martyrdom, Sacrificial Libation, and the Eucharist of Ignatius of Antioch is in restoring focus on the issue of martyrdom and sacrifice to the early church, especially in the aftermath of the destruction of the Jewish Temple by the Romans during the Jewish Wars. Klawiter draws upon the past few decades of scholarship highlighting the theological and spiritual crisis that developed from the Temple’s destruction and how early Christian practices were, in fact, in continuity with late Second Temple Jewish theologies. For instance, when discussing the Gospel of John, he writes, “The Fourth Gospel appears to show that the Johannine community was celebrating the festivals of Hanukkah (10:22-39) and Tabernacles (7:1-9:41) as being eschatologically fulfilled in the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus, the Messiah.”

Early Christian martyrdom theology continued this understanding of how through martyrdom the Christian becomes united with Christ and experiences the fulfillment of all Jewish hopes and expectations, “Rev. 6:9-10 shows martyrdom as a sacrificial libation that completes the sacrifice of the lamb in the Tamid Service. And given the spiritual crisis produced by the destruction of the temple in 70 CE for both Jews and Jewish Christians, the appearance of martyr shrines in cemeteries of western Anatolian Christians or house-church table-altars in the late first century would not be surprising.” Klawiter has done an admirable job restoring the emphasis on martyrdom and showing how the concept of martyrdom brings about unity with Christ in the writings of Ignatius instead of the now apologetic and systematic reading of Ignatius as presenting a theology of the eucharist at the neglect of the obvious fact that he is writing in route to his own martyrdom! Lest we forget that it is Ignatius’ own upcoming martyrdom that spurred his writings that we have in our possession today and not an attempt to write down a proto-systematic sacramental theology as apologetic approaches necessarily imply even if unconsciously.

However, Klawiter acknowledges that his approach is not substantiated by the majority of even critical scholars. If Klawiter is right, then he is the first person in the near 2,000 years of Christian history to actually get the eucharist right, and throughout his work he shows just how important the eucharist meal was to early Christians and why it remains the central focus of most Christian denominations in the twenty-first century. Considering just how essential the eucharist meal was to early Christians, as clearly testified to in Ignatius and then other second century writers, the reader is left wondering how Christianity could have gotten this important element of their faith so wrong if Klawiter’s general thesis is correct.

As such, the reader is left unconvinced that Ignatius’ view of the eucharist was entirely tied to a developing theology of sacrificial martyrdom. The issue, here, is not whether Ignatius understood the eucharist “symbolically”—for the eucharist does have multiple meanings and signification even within those theologies that affirm a realist presence—but whether the practice of eucharistic libation in late first century and early second century Christianity was largely (if not entirely) tied to a theology of martyrdom that developed as a sort of sacramental eschatology following the destruction of the Jewish Temple by the Romans. Despite Klawiter’s valiant revisionism, I’m inclined to think not standing the company of the majority of scholars who hold to similar views.

Klawiter illuminates for the reader the importance of martyrdom in Ignatius and how it was his upcoming martyrdom that caused him to write his important letters. This shouldn’t be lost on any reader of Igantius’ letters (and sadly, it often is). Nevertheless, as my former patristics professor at Yale said when discussing Ignatius, “Ignatius was also writing to comfort his flock about his impending death and to ensure the protection of their practices.” Not everyone Ignatius knew and spiritually tended was going to experience martyrdom like him, and those who were not going to be martyred and never martyred partook of the eucharist just like the martyrs did. Something more than mere martyrdom united the early Christians in the agape meal. Not everyone was going to experience a martyr’s death – so what was the significance of the eucharist to them?