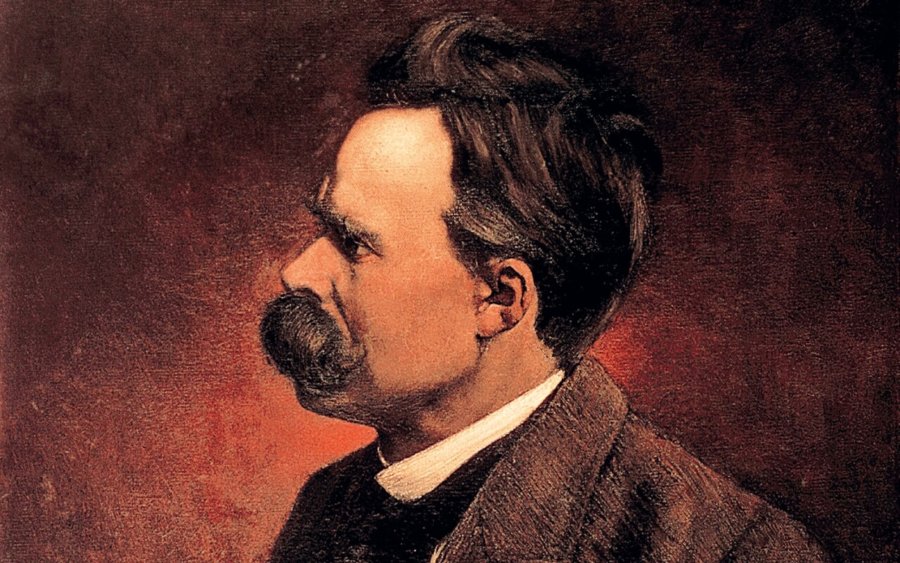

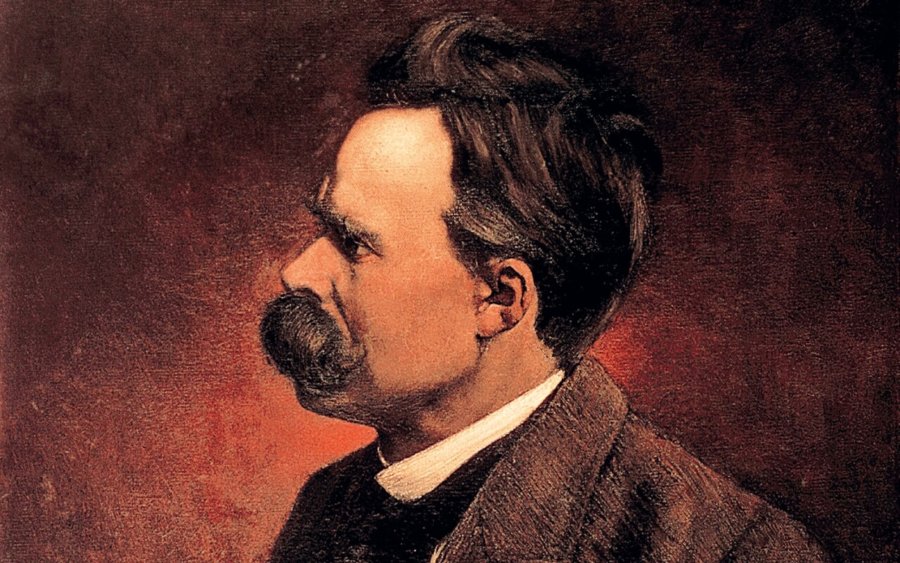

Timothy H. Wilson is a Part-time Professor in English Literature at the University of Ottawa, specializing in Early Modern Literature and Literary Theory. His recent research has focused on the “quarrel of philosophy and poetry” within the Western tradition, bearing fruit in a number of recent articles and papers on the manifestation of this quarrel in the political thinking of Plato, Shakespeare and Nietzsche. He is also the Associate Vice-President of Research Programs at the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Prior to joining SSHRC, Timothy held a number of executive positions within the Treasury Board Secretariat and the Public Service Commission of Canada.