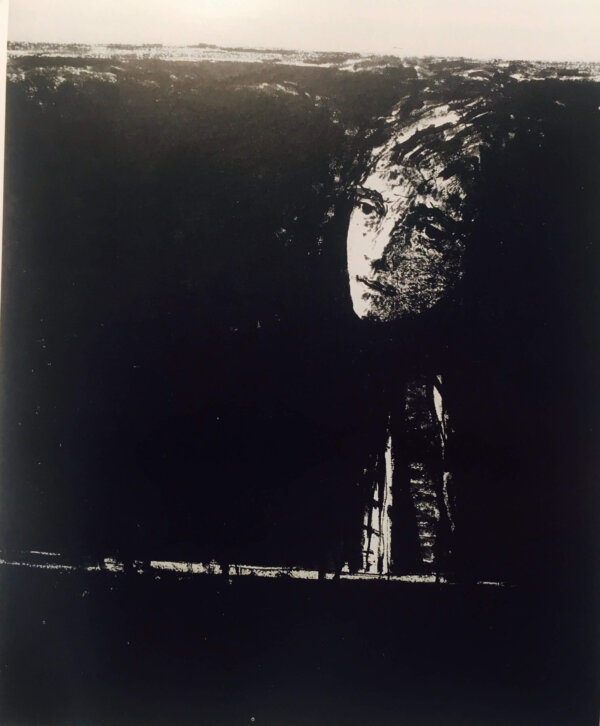

What’s Unconscious?

In recent columns, I’ve written about the mysterious effects of mind on body and their unpredictable intertwinings.

One reader has left Comments on these columns, twice urging me to read John E. Sarno’s book, The Divided Mind: The Epidemic of Mindbody Disorders. I’d never heard of the book nor of its author, but – ever on the lookout for a cure for my neuropathy – I sent for and am now reading it.

Sarno is an M.D. and six of his book’s ten chapters were contributed by other doctors who’ve treated (successfully I assume) an array of physical illnesses that they deemed of mental origin.

Here’s the book’s thesis, so far as I’ve got it: people often meet with experiences that generate rage. That’s a dangerous emotion, socially unacceptable, and liable to get one into fisticuffs or worse. Therefore, the conscious part of the mind prudently represses it. The rage then goes into the unconscious, but it doesn’t lie there passively. Rather, it produces somatic disorders whose chief function is to distract the mind so that conscious attention goes to the physical trouble rather than the rage beneath it.

What’s my view? Well, as a matter of fact, in the recent column where I tried to track my neuropathy’s pathway back to its origin, I’d arrived at a view not unlike Sarno’s. First, I’d noticed more suffering than I like to remember. Then I saw that I’d done my best to learn from each negative experience, transcend it and move on. But I considered the possibility that my body had refused to transcend anything or to move on! And that my neuropathy was just that somatic refusal!

So in a sense Sarno was breaking in open doors. The stumbling block for me lay in his dedication to Freud. What did I have against Freud? Well, I came to adulthood in The Freudian Years of American culture. I’d seen some of my finest, most sensitive friends emerge from psychoanalysis – “cured” – that is, psychically flattened, their self-understanding reduced to its lowest conceivable level. As if they’d undergone a moral and spiritual lobotomy!

Freud had a tripartite diagram of the psyche: id, ego, and superego. The id was the primitive level, amoral, and endlessly self-aggrandizing. The cured “analysand” emerged able to trace every motive and feeling down to the id as its cause. Creativity became the byproduct of the id, repressed and sublimated. The same for any high-minded speeches or expressive acts. For people who considered themselves educated and sophisticated, observing others became the tedious game of seeing through them.

What did this mean for women? After college, I avoided Freud till I read Dora: An Analysis of A Case of Hysteria, in preparation for a course I was teaching on “Philosophic Foundations of Feminism.” What I now recall of Dora was that, at a certain point, the poor girl found herself trapped in the unwelcome embrace of a middle-aged, bearded friend of her father and, quite naturally, wanted to gag. This reaction was deemed by Freud “hysterical” because it involved the transfer of the sexual feeling from the genitals to the throat. For my part, I would have very much liked to thwack him.

The abysmal disrespect, the failure of chivalry — the triumph of gaucherie, vulgarity, and cynicism — all seemed to me a cultural disaster and I wrote a fair number of articles disputing one or another of Freud’s claims.

Now I was rethinking the matter in my own case. Before reading Sarno, I’d already conceded the possibility that my neuropathy might be the result of somatizing a long stretch of suffering. Might not the suffering itself be anger internalized?

I’d lived a life that gave as little attention to anger as I could. Now I decided for once to take the gloves off and look, pointedly and specifically, at the rage in itself, in a particular instance, apart from its suffering aftermath. If I did that, what would I see?

What happened wasn’t anything I saw! To my astonishment, I could feel my heart beating wildly – almost dangerously – as if the precipitating event had just happened! My goodness! Who knew?

According to Sarno, evidence that a physical disorder arises from a repressed dangerous emotion becomes apparent when the first illness is cured but another dysfunction soon shows up to take its place. He calls this syndrome “the symptom imperative.”

If he’s right about some illnesses – and if his analysis has application in my own case – it follows that, even if my neuropathy were cured, I’d succumb to a new disability that would do the same work: masking repressed feelings of anger or rage.

Yipes! I don’t trust Freudian analysis and don’t go in for reductionist explanations of the human psyche. However, the psyche’s tripartite structure is not Freud’s invention. The classical philosophers too had a three-level psyche, with an appetitive bottom layer, a spirited middle level, and a rational upper level. Plato had it. Aristotle had it. And they were not reductionist. In their view, the healthy soul’s appetitive level had its natural place but took guidance from the two higher levels.

So reason does not require that the creative, loving, aspiring, rational, or spiritual operations of the psyche be explained in terms of whatever parts of ourselves we share with life forms that came along “earlier” on the evolutionary time scale. It’s still possible, without reductionism, to give the appetitive level another visit.

That said, I wish I knew how to go on from here.