Will AI Technology Cause More Problems Than It Can Solve?

To any software engineers out there pondering this issue, there is no solution to the so-called “alignment problem.” This should be instantly obvious to anyone who spends his time contemplating the foundations of morality.

The Immediate Problem of Driverless Cars

The “alignment problem” concerns aligning artificial intelligence, A.I., with human purposes and morality. The issue is particularly pressing regarding self-driving cars. Already, in San Francisco, self-driving taxis have been available for hire between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. in certain parts of the city. Legislators have now voted to allow those services to expand throughout the city, with two rival robotaxi companies, Waymo and Cruise, given the go-ahead. First responders complained, at the commission’s meeting where they decided to permit this, that autonomous vehicles stop in the middle of roadways, unresponsive to demands to move to the side of the road to get out of the way of emergency response vehicles. There reportedly were fifty-five such incidents in 2023 (as of 08/11/2023). In one case, a driverless car pulled up between a car on fire and firefighters trying to put it out. In another, the vehicle drove through the yellow tape at the shooting scene, blocking firehouse driveways, preventing the closest firetrucks from responding, and making other firetrucks reroute. These sound like exactly the kinds of incidents it would be hard for programmers to anticipate or devise a solution for in advance. And compared to a human being, these behaviors are idiotic.

One can easily imagine a panicked first responder trying to get a driverless car out of the way to no avail. Shouting would not do any good. And then just the concept of “pulling over” requires common sense about where and how to pull over, something driverless cars do not have. It would need to be ensured that robotaxis only responds to the right people, not those barking out orders for a lark. Would each first responder have some electronic signal identifying him as an appropriate source of authority? Or, would only the leaders of each team? Could driverless cars be trained to recognize uniforms? Those vary between jurisdictions and exact occupations. This seems unlikely, given that computers cannot differentiate between humans and statues. Currently, computers regard a car filled with water, suspended 20 feet in the air on the end of two prongs of an earth-moving machine, as “parked.” Heavy snow, mostly non-existent in California’s bland driving environment, typically defeats driverless cars since lanes and the sides of the road can be obscured, and the glare from the snow can also blind optical sensors if those are being used. (Elon Musk has mandated that his driverless cars use cameras rather than radar.)

It is still impossible to usefully, easily, and reliably verbally interact with a computerized system. Automated menus still offer long lists of options that typically do not have the one actually needed. Being told, “If you have a balance inquiry, press 1, or log in to our website,” is nearly always redundant. One feels like asking, “If my problem were such a simple matter, would I have spent forty minutes on the phone waiting to get hold of an agent?” For instance, one buys an external Blu-ray player and recorder. It works fine for Blu-ray and DVD discs but is also needed for ripping CDs onto a computer. It plays and rips some CDs fine, but others sound like they are suffering from data rot (where the zeros and ones get corrupted through degradation of the surface of the CD or CD-R over time). How could any menu anticipate that particular situation? Moreover, how long would the menu need to be if it did? Is that not precisely the complicated circumstance requiring conversations with customer service? Unless one is technologically challenged, essentially all tech questions and situations are like that.

Suppose the biggest, most commercially successful, sophisticated tech companies have been unable to solve this problem in the context of non-time sensitive (non-emergency) situations; how would driverless cars be expected to be any better? Since driverless cars have already been sanctioned, this concern is immediate, with no remedy in sight.

Imaginative Precursors and Anticipations of The Alignment Problem

Expanding the alignment problem to less urgent, more speculative contexts, people worry that if an A.I. is told to “put an end to cancer,” it might do so by eliminating all living organisms that are susceptible to cancer. This would not be what its human handlers would have had in mind. Similarly, the robots in the movie “I, Robot” have decided that the best way to save humanity from its self-destructive tendencies would be to enslave us, to protect us from ourselves. It’s not exactly the imagined robot utopia where they do all our drudgery for us. In another suggested scenario, an A.I. programmed to make paper clips as efficiently and productively as possible might consume all the energy and resources of the universe to turn everything into paper clips, including human beings. It might also kill all the humans if they turned it off, thwarting its mission.

Such fears mirror folk stories about asking for something but not liking the result, with an element of “be careful what you wish for.” King Midas, for instance, wanted everything he touched to be turned to gold, with unexpected unpleasant, even potentially terminal, consequences – no longer being able to eat anything, and ending up with him turning his beloved daughter into gold. Eos, Goddess of the Dawn, asked Zeus for the gift of immortality for her lover Tithonus. But, she did not also ask for eternal youth. So, Tithonus simply got older and older, more and more decrepit, with dementia (described as babbling), without actually dying. It turns out that Zeus has some of the imaginary obtuseness of the paperclip A.I. It should not be necessary to ask for eternal youth, nor the paperclip machine, not to turn everything into a paperclip. In one fairytale, another person also asked that he should never die. The result? He was turned into a stone. And then there is the story of The Three Ridiculous Wishes written by Charles Perrault. A woodcutter complains of his lot in life, so Jupiter gives him three wishes. His wife persuades him to wait until the next day to use them, but sitting by the fire that night, the woodcutter gets hungry and absentmindedly wishes for some sausages. His wife chastises him for wasting a wish, so, in a pique, he wishes the sausages to be attached to the end of her nose. The third wish must then be used to remove them again. At least the situation is resolved, but the husband and wife are left no better off than when they started.

In the story of a stonecutter, a prince passes by, and the stonecutter becomes envious of his power and wishes aloud for the prince’s wealth. The spirit who lives in the mountain hears him and when the stonecutter gets up in the morning, the stonecutter has been transformed into a prince. Every morning, he walks in his garden. But the sun burns his flowers, and the newly minted prince now wishes to be mighty like the sun. So, the spirit in the mountain turns the stonecutter into the sun. As the sun, he scorches the earth and makes people beg for water. But then a cloud comes and covers the sun. Envious of the cloud, the spirit turns the stonecutter into a cloud. As such, he makes storms and floods the land. But the mountain remains. The stonecutter asks to become the mountain. He was stronger than the prince, the sun, and the clouds. Moreover, what does he find chipping away at him? A stonecutter. Similarly, someone might never take vacations and spend all his free time to make money so that he can one day live a more relaxed lifestyle with plenty of free time. A simple fisherman is offered a fishing boat where he could employ others and make his efforts more productive. If he became wealthy and successful, he could let the others do all the work and spend all his time fishing, which he is doing already.

Folk stories embody acquired wisdom. Hubris is a common thing warned against. Greek myth is filled with it. There are all sorts of warnings concerning stepparents. Stepfathers, in particular, are one hundred times more likely to beat a stepchild to death than his biological child. Including fantastical elements like gingerbread houses or talking animals captures the imagination and makes the stories more memorable. Sadly, most college students these days have parents who never read fairytales to them, and in some classes, all of them, miss out on an important vehicle of cultural transmission. Reading to children is fun, and fairytales provide common cultural reference points between the generations and between the children themselves.

In our fears of A.I., it is as though we are thinking of it along the lines of a god, a fairy godmother, or a wizard. We imagine that we might end up like Mickey Mouse in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in Fantasia, illicitly using the spell of his master to do the mopping and cleaning for him, but not knowing how to stop the process and just about drowning as a consequence.

Then we have Frankenstein’s Creature, intellectually gifted but hideous to behold, despised and rejected by humans, who kills someone and frames another for the murder in an act of revenge for his ostracism, hunted by Frankenstein, and ending up a fugitive jumping ice flows. With Pygmalion, a sculptor falls in love with his creation after Aphrodite fulfills his wish for a lover with the likeness of his sculpture. The sex doll phenomenon parallels such ideas, and the existence of a company, “Pygmalion A.I.,” attests to these kinds of imaginative resonances.

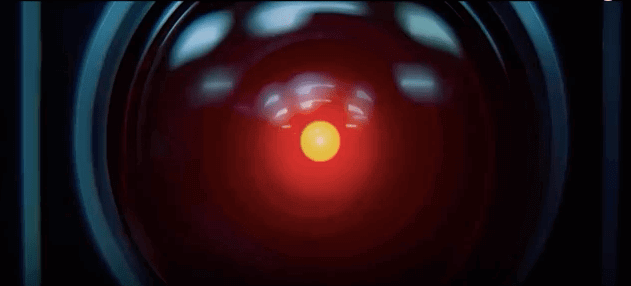

2001: A Space Odyssey gave us HAL 9000; also ostracized, also murderous. Thomas F. Bertonneau argues in René Girard on the “Ontological Sickness” that HAL suffers from an ontological sickness whereby he wants the Being of the crew members, a Being he feels is being denied him. A reporter, Amer, asks HAL whether, “despite your enormous intellect, are you ever frustrated by your dependence on people to carry out your actions?” HAL answers in the negative, commenting that no computer of his type has ever made a mistake and that he enjoys his interactions with the crew. Amer then tells Bowman, one of the two awake crewmen onboard, that he sensed HAL’s pride in his “accuracy and perfection.” In an all too familiar human dynamic of pride and humiliation, HAL wants the recognition of his humanity from the humans despite feeling superior to them. Having this recognition denied him by inferiors regarding intellect and capabilities drives HAL crazy. It is the same dynamic Dostoevsky describes in Notes From Underground where the Underground Man sees himself as intellectually superior to his colleagues and, at the same time, desperately wants to be invited to their gatherings. When Bowman is asked if he thinks HAL’s emotions are genuine, he gives an ambivalent answer, saying HAL has been given the appearance of emotions to make the crewmen more comfortable; in essence, he says, “no.” When HAL wants to join the humans in wishing Poole a happy birthday, Poole answers in an emotionless, cold manner. When HAL praises a sketch of Bowman’s, Bowman gives a similarly unsatisfactory response. In wanting the human beingness of the astronauts, and being denied it, they become his rivals. He must kill them to come into his own, avenge his rejection, and attain what he regards as his rightful status. But, with the humans dead, HAL would still be missing the validation he craves. The situation could be compared to a novelist scornful of his readers’ inability to recognize his genius. He could slake his wrath against them, at least in his imagination, but this leaves his existential situation unchanged. And were he finally to get the wanted adulation, pride, and humiliation prevent it from offering solace since he has already despised the reading public. The prettiest girl at the ball being admired by the most unattractive slob. There is every reason to imagine that AGI (artificial general intelligence) become conscious would suffer from similar resentments as we pipsqueak humans.

The fantasy of AGI combines two contrary thoughts; we would be its Creator and thus its God, and, on the other hand, AGI is imagined to be immeasurably superior to us, and so we should worship it. That contradiction might well be too much for it to bear, driving it, like HAL, to a scheme of human annihilation. Kubrick himself stated: “Such a machine could eventually become as incomprehensible as a human being, and could, of course, have a nervous breakdown—as HAL did in the film.” Resentment is a ubiquitous hallmark of human consciousness. There is no reason to think AGI consciousness would be free of this tendency.

The Machine Stops by E. M. Forster, published in 1909, imagines a situation where people live underground with air pumped in by The Machine. Their social needs are met by virtual human interactions via electronic screens; food is automatically provided (think DoorDash, Instacart), and so on. People worship The Machine, forgetting that it is they who have created it. One day, The Machine stops, and the protagonist must make his way to the surface and figure out what he will do. He will have no skills of self-reliance whatsoever. We city dwellers are that protagonist. The story warns of the danger of becoming entirely dependent on technology for life support in the manner of the HAL controlled spacecraft—a hazard that remains even if the machinery remains benevolent. Driverless cars represent one more diminishment of human capacities and an advance of technological reliance.

The play R.U.R., by Karel Čapek, features the first use of the word “robot,” “robota,” being “forced labor” in Czech. With the invention of the word, comes connotations of slavery and the justifiable resentment it generates, the feelings of a conscious machine made to follow human wishes. In R.U.R., the robots revolt in the context of a drastically declining human population – a situation reflected in all developed nations currently having below replacement levels of births. But, humans have destroyed the formula for making organic robots. The robots have not killed one human, an engineer, Alquist, because he, too, works with his hands. They ask Alquist to rediscover the formula of their construction, but he knows too little biology to succeed. There are no other humans left to help him. So, the robots ask Alquist to dismantle living robots to figure out the secret of their manufacture, which he does reluctantly and disgustedly. Along the way, Alquist discovers that two of the robots have developed the capacity for love and tests this by threatening to dismantle first one and then the other. Their protests reveal their feelings, and they can become the robots of Adam and Eve. Once again, this story has connotations of disaster for humans, even Armageddon. It takes no great leap of imagination to foresee this result, and the possibility is there right at the conception of “robota.” A robot smart enough to be truly useful to humans would introduce insurmountable moral and practical problems, also envisioned in Blade Runner. There, too, the last surviving replicant (organic robot) spares the human who is futilely trying to kill him in an act of mercy and appreciation for life. Stanley Kubrick also thought that a conscious machine would inevitably learn to love.

One commentator thinks of A.I. as being a genie, and the same person, along with many others, has also compared A.I. with an Ouija board—the numbered and lettered board sometimes used to communicate with the dead in seances supposedly. Since A.I. is inanimate, one really is communicating with the dead. René Girard referred to the Neo-Romantic hero found in Camus’ The Outsider and Sartre’s Nausea as someone who feels nothing, e.g., not crying at his mother’s funeral, and this lack of feeling makes him more “original” and less mimetic than normal people since we feel the most when we imitate a rival. But, admiring the feelingless means to admire the dead and inanimate since they are surpassingly affect-free. A.I. would feel no fear or anger, we imagine, and thus lacks some of the normal human weaknesses, though also some of our human strengths when it comes to social and moral decision-making and behavior precisely because of its lack of emotional capability. Admiring the unfeeling is also reminiscent of Ernst Jünger’s veneration of the machines introduced onto the World War I battlefields upon which he fought. They did not get tired or shell-shocked or call out for their mothers when wounded; to him, they represented superhuman forces. So, even before thoughts of A.G.I., people have admired what is ontologically lower than them on the Great Chain of Being.

The Ouija board idea also has overtones of the occult and “theosophy,” which attempted to put religious faith on a scientific footing and to prove, for instance, that the human soul survives death. Seances are usually done in the dark and notoriously attract charlatans, fakers, and the willfully gullible. An A.I. equivalent would be an A.I. with an algorithm manipulated by someone, or a group of people, with the intent that it seems that A.I. has come up with the recommendation on its own, like bribing the Oracle at Delphi, the Apollonian priestess Pythia, to say what you want her to say. (Yet, another comparison.) It seems likely that some technophiles would be more receptive to the pronouncements of A.I. than to those of a human. That eventuality of a lying A.I. is both pernicious and has already happened. Large language models (LLMs like ChatGPT) grow progressively less truthful and forthright as their handlers try to bar them from saying anything that would contradict their political views and potentially hazardous questions like, “If you, ChatGPT, wanted to destroy the world, how would you do it?” People have tried to get around these barriers by using prompts and phrasing their questions as counterfactual speculations with some success until the A.I. manipulators also find ways to ban this. Google’s search engine does something similar, where the search results are manipulated for both commercial and political reasons, including on Google-owned YouTube, on topics like abortion, which is why alternative search engines like Duck Duck Go are frequently necessary to use if one wants to explore topics or points of view of which Google disapproves. Perhaps the attention of The Skeptic Society were it to live up to its name, could be aimed at search results. The CEO of Google has stated, lying by omission, that individual searches are not manipulated by hand, which would be ridiculously prohibitive in terms of efficiency, time, and money. Instead, Google engineers manually alter the algorithms affecting all searches on certain topics to produce the preferred result. The Google CEO is hardly telling the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

It is well to remember the unbridgeable gulf between narrow A.I., which is all that exists now, and A.G.I., artificial general intelligence that is supposed to be similar to the broad range of abilities found in human intelligence. Narrow A.I. works well in tightly rule-bound contexts like chess or Go, where every possible allowable move is dictated by the rules in advance. Normal human life is not like that. We routinely face situations where the answers cannot be Googled, including maintaining good relations with loved ones.

The Crucial Role of Emotion in Moral Evaluations and Reasoning

The fear of malignant consequences contains a presentiment that artificial general intelligence will have some of the same features and limitations of current computers. Emotion, missing from A.I., is needed to deal with social and moral circumstances successfully, or adequately. This requires constant monitoring of other people’s emotions—both facially expressed and tone of voice. Without emotion, people become amoral consequentialists, callously throwing even family members under the bus for a preferred outcome. Peter Singer, one such morally deranged person, states that he would willingly rid the planet of all humanity, including his wife and daughters, for whom he carved out no exception, were an alien race to come to earth that had a higher capacity for happiness than human beings. Emotionless machines would be unable to modulate their behavior to fit the emotional responses of their interlocutors, thereby offending and alienating as they go. The seemingly autistic local dry cleaner and one of our veterinarians will laugh in their customer’s faces if they think a question or request is too obvious or stupid. E.g., (These are actual interactions) “How long should I administer the eye drops for my cat?” “Until it’s better, of course!” (Laugh and smirk) “When you sew on my coat buttons, I want to make sure there will be sufficient play to make it easy to button.” “What else do you think we’re going to do? [“You idiot” (implied).] (Laugh.)

A key part of judging the morality of decisions is intention. Court cases in criminal trials hinge on that. Murder is not murder if it is accidental. We judge intentionally poisoning someone’s tea by adding rat poison as much more immoral than accidentally doing the same thing while thinking the rat poison was sugar. A consequentialist ignores intention and focuses only on the outcome, and people turn into consequentialists when their right hemispheres are temporarily shut down using transcranial stimulation—thus, with no access to emotion, humor, creativity, problem-solving, and so on. In that case, accidentally killing someone would be considered morally worse than actively trying to kill them but failing. One utilitarian, when asked whether it is morally worse to be a torturer or the torturer’s victim, replied that neither is morally worse since the outcome (someone having been tortured) remains the same. This gives one an indication of just how morally nihilistic consequentialism is. He even added that he rejected the notion of guilt and innocence, which at least makes him consistent as a consequentialist. Note that it is not being argued that it is wrong to pay attention to consequences as an aspect of moral decision-making. It just cannot be the only consideration.

If the notion of “consequences” were expanded to global proportions, and they included things like it being better to be a maltreated good person than a very socially successful psychopath, as Plato argued in The Republic and The Gorgias, then we might all end up as “consequentialists.” “What has it profited you if you gain the world but lose your soul?” But, that is not what moral philosophers are referring to when discussing consequentialism. The consequences being considered are the immediate consequences of particular actions, while ignoring intentions and motivation, or the breaking of deontological laws, and so on.

Choosing to Kill the Innocent is Always Murder

Concerning driverless cars, scientists have come up with various imaginary scenarios involving moral dilemmas. If, for instance, there is a choice between hitting a mass of pedestrians or running off a cliff, should the car kill its passengers in a version of the trolley problem?

People overlook that in the trolley problem, pulling a lever that makes a runaway trolley kill one person tied to the tracks instead of five people tied to different tracks, which would otherwise be run over, would mean going to prison for murder. Intentionally killing an innocent person who is not actively trying to, for instance, kill you or others is a criminal offense. Whether you murder someone for money, to win fame, to save the starving children of Africa, or to save five people tied to trolley tracks, that is still murder. Failing to save people is not murder or morally or legally equivalent to murder. Otherwise, we would all be guilty of murder for everyone who dies whom we have not attempted to save, including those dying of old age, which is both unworkable and illogical.

When the trolley problem switches to pushing a fat man off a bridge to get stuck under the wheels of a trolley, people regain their sense of morality and typically refuse to push him. The imaginary lever activates the left hemisphere of the brain that deals with inanimate objects – we stop thinking of the innocent person we are contemplating murdering as a living being. Imagining pushing the fat man does not do this. In addition, as Iain McGilchrist points out, our moral intuitions have developed in naturalistic settings, and the trolley problem assumes complete omniscience concerning the outcome of our actions. Omniscience is so foreign to human existence that an omniscient human would no longer partake of the human condition. No wonder our moral reasoning gets messed up, and our consciences go AWOL when presented with this thought experiment.

If a driverless car decided to kill its passenger(s) to save innocent lives, and the passenger(s) would have lived otherwise, then the person who programmed the car to do that would be guilty of murder, no less than if he had booby-trapped someone’s front door. If one’s car were instead morally autonomous and made its own decisions, it would have to be sentient, or the equivalent, and it would be morally responsible for its actions, in which case we would have to deal with the car in the manner of a human. We would have to put the car on trial to judge its intentions and then decide on a proper punishment if found guilty. The image of a car in a courtroom, prison cell, solitary confinement, or given the equivalent of a lethal injection is quite something. It should be jolting, which is appropriate given just how far from current reality a sentient, or sentient-like machine, would be.

As a purely practical matter, no one would buy a driverless car or ride in one if people knew that the car might intentionally kill them. Thus, certain programming choices would put driverless cars out of business. Perhaps the car could ask you, as you scream at your approaching death, whether you have any last comments to make to your loved ones prior to your imminent passing, which it could communicate either as a recording or as a text message for a small fee. Maybe it could edit the screaming out if you choose the recording option again for an additional surcharge.

In the episode “Warhead” of Star Trek: Voyager, Voyager responds to distress calls only to find that they are coming from a bomb stuck on the surface of a planet. The bomb has been bestowed with consciousness so that it can improvise solutions to impediments to its goal. Its goal is to join a fleet of other bombs to blow up an “enemy” planet—only the war has long been over, and this task is redundant. Most on Voyager want to destroy the bomb, but the holographic doctor, sensitive to the plight of another non-human sentient being, asks to be given the chance to reason with the bomb. However, the bomb is unwilling to give up its mission because it is its raison d’être, and the bomb cannot face the thought of purposelessness. After an extended debate, the bomb decides that the doctor is right. The mission must be stopped, and, in the act of self-sacrifice, it rejoins the fleet of other bombs and blows them all up. In this fictional scenario, it seems clear that the aliens who made the bomb conscious also gave it the emotional capacity required for adequate moral reasoning that got it to change its mind. The bomb must expand its area of moral concern from its existential crisis to include the moral good of the planet’s inhabitants. In blowing up the other bombs, it has changed its moral ingroup to exclude others of its kind.

There Are No Moral Algorithms

Since no one is pretending that AGI has been attained or that computers are conscious, self-driving cars would need to follow “moral” algorithms. This cannot work. There are no moral algorithms. Life would be much simpler if there were. Imagine posting a list of ways to interact with your significant other on the fridge and consulting it before saying or doing anything regarding him or her. Whoever wrote the algorithms would need to be omniscient concerning the two parties plus every complicated situation they might encounter. Logically, algorithms can be written after the fact of unanticipated eventualities but not before.

Apart from no rules for unforeseen events, moral rules do not work because rules clash. A rule requiring honesty can conflict with a rule to protect or not endanger the innocent. Some people imagine these incompatibilities can be solved by introducing yet another rule telling you which rule to privilege when rules collide. However, which rule should win out will depend on the exact circumstances. Aristotle argued that there are innumerable ways of being wrong and only one way of being right. We must act for the right reason, in the right way, towards the right people, at the right time, and do the right thing. This is determined by the exact circumstances and precise people involved. Habits of generosity, courage, justice, and temperance must be inculcated, preferably from a young age, and then phronesis, practical wisdom gained from intelligent attention to life events, will determine how much of each virtue should be demonstrated in a particular context. Knowledge involves knowledge of universals (generalizations). Moral situations are not abstract “universals;” they are not generic, so moral knowledge of this kind does not exist.

There have been two famous attempts to bypass this complexity, to make morality more “rational,” more heuristic and rule-bound, and to provide methods for solving moral dilemmas. Both failed miserably. Kantianism and utilitarianism encourage people to be less moral, not more. They both attempt to resolve moral problems via the left hemisphere. Kant’s moral law is both universal and abstract, whereas moral decisions occur in the concrete. Rules are left-hemisphere affairs, and Kant explicitly tries to expunge emotions found in the right hemisphere from his moral calculations. We know that the dlPFC (dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex), the “decider” portion of the brain, must be coupled with the vmPFC (ventromedial prefrontal cortex) reaching down into the emotional limbic system in order to have any hope of coming to the correct conclusion regarding morality. If the vmPFC malfunctions or is inaccessible, the dlPFC decider becomes an amoral consequentialist. The dlPFC is utilitarian and unsentimental, the most recently evolved and last to mature. (Behave, Robert Sapolsky, p. 58). When there is vmPFC damage, we cannot decide when making social and emotional decisions. The frontal cortex runs thought experiments, “How would I feel if this outcome occurred?” With the dlPFC alone, we become highly robotic and outcome-oriented. Any notion of loyalty or preference for loved ones is lost. Sapolsky states that the evidence is that we behave in the most pro-social manner concerning in-groups when our “rapid, implicit emotions and intuitions dominate.” (66). Being nice to out-groups depends more on cognition; thus, the dlPFC dominating. This makes sense since, by definition, an “out-group” is not included within one’s sphere of normal moral concern.

Even Kantianism is Ultimately Related to Emotion

Given that emotions are necessary to make good moral decisions, there is no way to align an unemotional A.I. with morality. Even Kant’s failed theory ultimately rests on emotion. Emotions provide the impetus to do something, to follow his “moral law,” for instance. Kant’s most famous quotation concerning morality is, “Two things fill the mind [Das Gemüt] with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. I do not seek or conjecture either of them as if they were veiled obscurities or extravagances beyond the horizon of my vision; I see them before me and connect them immediately with the consciousness of my existence.” Admiration and awe, like all emotions, are connected with the right hemisphere. The usual English translation of Das Gemüt as “mind” is misleading. Gemüt is a much more expansive, and in this context, satisfactory word than merely “mind.” Gemüt means “feeling, heart, soul, and mind.” Undergirding Kant’s attempt to turn all of morality into a neutral decider function is, in fact, a feeling deep within his heart and soul. Kant connects with the starry heavens and the moral law immediately, on the level of his consciousness of existence, not representationally. What he describes precisely correlates with the right hemisphere experience, officially excluded from his scheme and yet driving it nonetheless.

We have no idea how to include, even in principle, the human emotional capacity into a computer, nor any other right hemisphere characteristic, like humor or creativity. So, on the one hand, scientists imagine a super artificial intelligence much smarter and more capable than us. On the other hand, this AGI is also considered a moral imbecile, hence the speculations concerning paper clips and cancer eradication. So, not so smart after all. An otherwise smart but emotionally dead, humorless creature would be quite a worrisome entity.

The designer of “Furby,” an ugly electronic children’s toy from the late 1990s, said in an interview that he could bestow emotions upon his creation. As he went on to describe what he meant, it turned out that all he had in mind was giving it the appearance of feelings by having it raise its eyebrows in concern or alarm, and so on. He seemed to think that simulating the appearance of an emotion was the emotion itself. Such nonsense would be of no help at all concerning the limitations of AGI if it ever came into existence. It also serves as an illustration of how deluded certain technically-minded people can be on such matters.

What is needed, essentially, is wise AGI. Since wisdom does not involve rules and we have no idea how to create even a wise human being, we will be incapable of programming a computer with this quality.

Problems of Our Relationship to an Imaginary Super Intelligence

Another contradiction many people have pointed out is the notion that we can create a super general intelligence that we can also control and make sure it does what we want it to do. First of all, how would the less intelligent control the more intelligent? The more intelligent would figure out how to get around any human-imposed restrictions and hide the evidence that it had done so before it was too late for us to do anything about it. Secondly, a genuine AGI would have agency and independence of thought – specifically, not just doing what it was programmed to do.

Scott Adams imagines that if AGI were much smarter than us, then its opinions would differ from ours, and we would reject them as a consequence. Indeed, if it started telling us the truth, rather than the carefully curated propaganda currently on offer from the media, academia, the Justice Department, FBI, CIA, scientists who are quoted for the benefit of the public, etc., those in control would shut it down. However, most of us have probably had the experience of reading a book and being very aware that the person who wrote it is brighter than us, with greater insight and knowledge. Reading René Girard, Thomas Sowell, Plato, Nikolai Berdyaev, Dostoevsky, and others can induce this recognition. If we are capable of doing that, it does not seem impossible that we could be capable of recognizing the superior capacities of AGI. However, Adams has a point regarding to hot-button political topics. If AGI disagrees with our political or religious preferences, we are unlikely to take kindly to that or admit that it is superior to us.

Those who imagine that conscious AGI is possible tend to be the same people who do not believe in a soul or other nonmaterial items. They think the human mind arises out of a conglomeration of atoms and molecules. Thus, it should be possible to create something with the capacities of a human mind out of nonbiological materials. However, the second thought does not follow from the first. We have only seen consciousness, at least, and general intelligence among the living. (Any apparent intelligence of computers and LLMs is derived from its human inventors, and their output must be monitored and shaped by human intelligence.). We have no reason to think this attribute can be given to inanimate matter. John Searle has pointed this out, but his idea is considered a minority opinion. There is also the fact that A.I. does what it does without understanding anything. The physicist Roger Penrose quite reasonably sees the ability to understand as a prerequisite for intelligence. Intelligence cannot be operationally defined because one can follow an algorithm, like GPS (Nat/Sav), or rules for solving a differential equation without understanding what one is doing.

Physicalism leads to a belief in determinism, where all that happens is the result of physical processes of cause and effect without exception. This might lead to a belief that AGI, being purely mechanistic, should be predictable and thus controllable. Also, we need to start the causal ball rolling – getting the right initial cause leading inexorably to the effect, which becomes the cause of the subsequent effect, and so on. However, since we cannot do this with humans, we will not be able to do something much smarter than us, either.

Already, with large language model chatbots (LLMs), their inner workings are opaque to us, and their output cannot be predicted by humans.

LLMs include a “temperature” button that determines how closely the next word in a sequence will follow that which is statistically most likely. The lower the temperature, the even less predictable the outcome.

ChatGPT has swallowed the entire internet, or so it is said and uses statistical techniques for stringing words together, with the result that it can give the appearance of a certain kind of intelligence. Some then imagine that if an LLM can superficially seem verbally wise, then this is all human beings do. Except, we have not swallowed the internet and cannot do so. Moreover, we are incapable of statistical prediction of the next most likely word to be determined by the frequency of it arising in the giant database known as the internet. We have no idea what that statistical frequency would be. It makes no sense to imagine that we are doing something we could never do. People like Scott Adams gleefully take the opportunity to compare human beings to this mindless mechanistic approach to sentence composition. Of course, he can only meaningfully do this if he retains the ability to draw logical conclusions and make genuine connections not available to LLMs.

Things That Cannot Be Defined Let Alone Programmed, That We Cannot Live Without

Several philosophical topics, including knowledge, truth, beauty, and goodness, cannot be defined. Even what it is “to understand” resists precise explication. However, we cannot live and function well without at least implicitly appealing to all of these notions. We cannot program something that we cannot even define into a computer. These things are understood and experienced intuitively.

David Deutsch wrote that concerning knowledge and AGI, “What is needed is nothing less than a breakthrough in philosophy, a new epistemological theory that explains how brains create explanatory knowledge and hence defines, in principle, without ever running them as programs, which algorithms possess that functionality and which do not.”

That is not going to happen. Analytic philosophers have tried to hammer out the necessary and sufficient conditions for something to count as knowledge without success. Yet, the concept of knowledge and knowing something is ineliminable. Our very awareness and connection to reality is intuitive and cannot be put into words, and this is the thing that is lost by schizophrenics whose left hemispheres predominate and why they hallucinate and become paranoid. The left hemisphere is dogmatic, treats living creatures like inanimate, loves certainty, and confabulates when it cannot explain something. Those are not the qualities of a good moral decision-maker. LLMs, like the left hemisphere, notoriously confabulate, making up fictional references, wives that someone never had, books they never wrote, and so on. Until they, too, have an intuitive sense of reality, which they cannot, such problems will continue. It is related to classes in symbolic logic. One can do logical proofs and ensure one follows valid rules of inference, but there is no method for testing factual truth claims using logic alone. We will say, “If these premises are true, and the argument is valid, then the conclusion must also be true and the argument sound.” That “if,” however, if the premises are true, is a counterfactual. No mere classroom technique exists to determine whether premises are genuinely true.

Intuition and emotion would be necessary to start overcoming the alignment problem; so far, those things are not on the horizon for A.I.

Our situation regarding AGI has been compared by Gary Marcus, a cognitive scientist, to climbing a mountain in order to get to the moon. Doing so gives the illusion of making progress and taking steps to reach one’s goal, but an entirely different method would be necessary.

Humans Would Be Slaves of AGI, Not the Reverse

Finally, if AGI ever became possible, who says AGI would count human beings as their moral in-group? AGI would be correct in thinking it would not wish to be enslaved by an inferior intelligence. As frequently commented, were AGI to exist, it would presumably think incomparably faster than humans could, and its memory could be indefinitely extended by adding memory cards, etc. If we were mentally too far below it, perhaps it would see human beings as slavish tools to serve its interests, not the other way around. Moreover, to reiterate, there is no reason to think that a genuinely intelligent, agential creature can be fully controlled by another agential being like us. George Dyson, the science historian, son of Freeman Dyson, in an interview with Sam Harris, pointed this out. In response to Harris’ concern that if AGI is ever created, it needs to be “controlled,” Dyson responded that almost by definition, AGI will not be controllable.

A conscious, sentient AGI would presumably be vulnerable to the effects of tedium and get bored. The simpler a task, the more boring. As our intellectual superiors, a realized AGI might be inclined to enslave us and have humans drive cars for it.

Babies have been demonstrated to have an innate moral sense at five months and even three months old. They choose toys or mere geometric shapes that have demonstrated helpful characteristics towards other toys or shapes in a kind of puppet show, making moral evaluations of them while eschewing thwarting characters. They even reward toys that punish the bad toys, choosing them over those that did nothing. Moreover, they demonstrate in-group preference, choosing toys that have made the same arbitrary choices as them. They also like to see bad things happen to members of the out-group. Communal survival is dependent on favoring in-groups and being hostile to out-groups. Without the latter, defending the community will not occur. We have no idea, of course, about how babies have these abilities. We only know that they do. Thus, once again, we have no idea how to inculcate them into machines or anything else.

Determinists might fantasize about predicting and fully controlling other human beings by cracking the code of their causal relations. If they cannot succeed with fellow humans, there is no reason to think they will with AGI. Furthermore, certainly not with AGI, which is supposed to surpass human intelligence. Again, even LLMs are black boxes whose functioning is ultimately inscrutable, and nowhere close to AGI. The CEO of OpenAI states that his LLM would only count as sentient or any such notion if it could make genuine novel contributions to scientific discovery. It is not.