Winters Contra Everybody

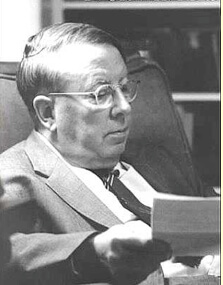

Yvor Winters, American poet, critic, and grouch, is by no means forgotten. Amazon lists 196 hits, including two selections of letters, and his magnum opus, Forms of Discovery, is available, although no one on Amazon has reviewed it. Never mind that, many of his pupils are still alive, and they cherish his memory.

And with merit too. Winters’ poetry stands up well to second reading–it is clear, polished and austere.

This is the terminal, the break.

Beyond this point, on lines of air,

You take the way that you must take;

And I remain in light and stare–

In light, and nothing else, awake.

-from “At the San Francisco Airport”

His literary criticism is a well of good sense and his core poetic stance– “post-symbolism”–is attractive. More about that stance later. Your columnist was introduced to the work of Winters by the late Dr. E. Bundy and has been reading Winters off-and-on for years: we have never met a dictum by Yvor Winters that was impractical, immoral, or low.

But in present-day culture wars, Winters is, alas, not a player. He was caviar for the general, and the general has walked away.

Why this neglect of solid merit?

(Arthur) Yvor Winters (1900-1968) was born in Chicago, attended the University there, and afterwards the University of Colorado and then Stanford. He joined the staff of Stanford and taught there until his death. He published several books of criticism and a lot of poetry.

Winters began in the twenties as an imagist poet:

Earth darkens and is beaded

with a sweat of bushes and

the bear comes forth;

-from “Quod Tegit Omnia”

Around 1930, however, he made an abrupt course-change. He forswore his allegiance to the sensory image and adopted rationality.

By then he had probably already grown dissatisfied with modernism, but his own crisis may have been nearer to a nervous breakdown. He seems to have concluded that some of his difficulties came from his previous a-rational poetic dogma. Most people would not take modernism seriously enough to let it drive them crazy, but Winters was, in whatever he thought important, utterly sincere.

At any rate, he took up meter, coherent English syntax, and coherent argument. He championed poets who fit his judgement–his alternative canon of English Literature became famous, or notorious.

Team Modernist soon learned all about the Chicago Way. Winters became the most feared critic in America, the scourge of a-rationality and un-rationality, sentimental indulgence, and loose thinking.

He did not varnish his statements:

“I do not wish to say that I believe that Yeats should be discarded, for there are a few minor poems which are successful, or nearly successful . . . “

-from Forms of Discovery

Re-reading his criticism one notes with admiration that he was very often perfectly right, and it is great fun to read.

But . . .

Winters wrote like a prosecuting attorney. When it came to a choice between the sun and the north wind, he took the wind’s part every time:

“. . . But it is foolish to think of [William Carlos] Williams as a great poet; the bulk of his work is not even readable . . .”

-from Forms of Discovery

Now it is pleasant to be right. But if you want to change hearts you must persuade. Antony knew that, and Brutus didn’t. And if you aim at a general reformation in some very important matter, such as literary art, something into which many people have invested time and care, you will not induce them to change their methods by declaring a me contra mundum stance.

Because the world will win, bank on it, and what you offer will be wasted.

It is a true thing, that those who got past Winters’ satyr shell found within a golden image. But not many were willing to make the effort. So, even today, his disciples are dedicated, but scarce. The medicine is wholesome but how many who need it even know it is there?

The other problem with Winters is more difficult to put into words.

Winters had developed a critical position he called “Post-symbolism.” It is outlined in detail in the fifth chapter of Forms of Discovery.

As we understand it, in brief, it involves (a) intense observation of phenomena, whether an ocean swell or a bird, (b) understanding of the phenomenon at hand as an instantiation of rational concepts, (c) description of the phenomenon in a poem is such as way as to make its metaphysics clear, either explicitly or implicitly, (d) use of the standard poet tools, especially meter, to suggest the appropriate emotional reactions to the concepts.

This is a program designed to appeal to the adult mind.

We have observation and sensuality (making the poem immediate and pleasant); we have thought and if we are lucky profundity; we have a wide space for the exercise of poetic skill.

So why isn’t this taught in grade schools?

Your columnist sees with a sigh that it is climb-out-on-a-limb time again.

I suggest, with diffidence, that the difficulty goes back to the odd fact that that Winters, although a great admirer of Thomas Aquinas, was an atheist and a fairly thorough one too. Like Nathaniel, deceit wasn’t in him.

He was committed to rationality, the highest natural excellence. But the majority of the human race are Aristotelians, in that they recognize that concepts are primarily in things. They will not be satisfied with concepts, they want a reality, in fact they won’t be satisfied with less than Reality itself. But that cannot be a collection of concepts. It must be a fact, and in fact a personality. Without that transcendent beam, no rope will hold.

It is a surprising fault for an admirer of Thomas. But from this problem, Winters could not extricate himself, on any terms he could or would accept. But within his own rules, he made a noble effort and deserves our remembrance and admiration.