(Without) the Reason of State, with the Autonomous Technicality of Disease Prevention

Can we arrive through reason at knowing what is the reason of state? For if unreason should come into conflict with reason, we shall then reason and not unreason, because it would be impossible to retain that our reason is senseless, that it only attracts pain and disease, so it holds nothing. In this recent follow-up article of those published in the 20 September, 13 October issues of VoegelinView we have a reason to believe that nothing has no reality, no degree, where no things bring that what is good; when the reason of state is holding back the desire for good life merely in order to satisfy delirious passions which lie deeply and ever more completely hidden in the abyss. In this way the reason of state became a mere technique of statecraft, a mindless autonomous technicality, more or less covered by the word artificial intelligence, which therefore anthropologically speaking is not at all a modern invention. Whenever the feeling machine (a term coined by Leibniz[i]) is set into motion, it lures people to a life of misery, a perplexing monstrosity with material abundance, but subverted individuality, just like in Oriental Despotism.

In any event, the notion of the reason of state goes back to Machiavelli, as it was masterly analysed by Friedrich Meinecke (1984),[2] the German historian, just after WWI. He argued that the reason of state is continuously in danger of becoming a merely utilitarian mechanism without special ethical application, as it is in constant exposure of sinking back again and again from the mindful senses to mere cunning (ibid.: 7). But before Meinecke, Hegel[3] had something to say about reason, through the cunning of reason. Briefly, this doctrine holds that while reason is forever present, we can reach it by placing a pistol at our throat, as reason has the power to harm, which is the cunning, indirect way to truth. In other words, according to Hegel reason fulfils its ulterior rational designs by irrational pain and sacrifice in delirious passions.

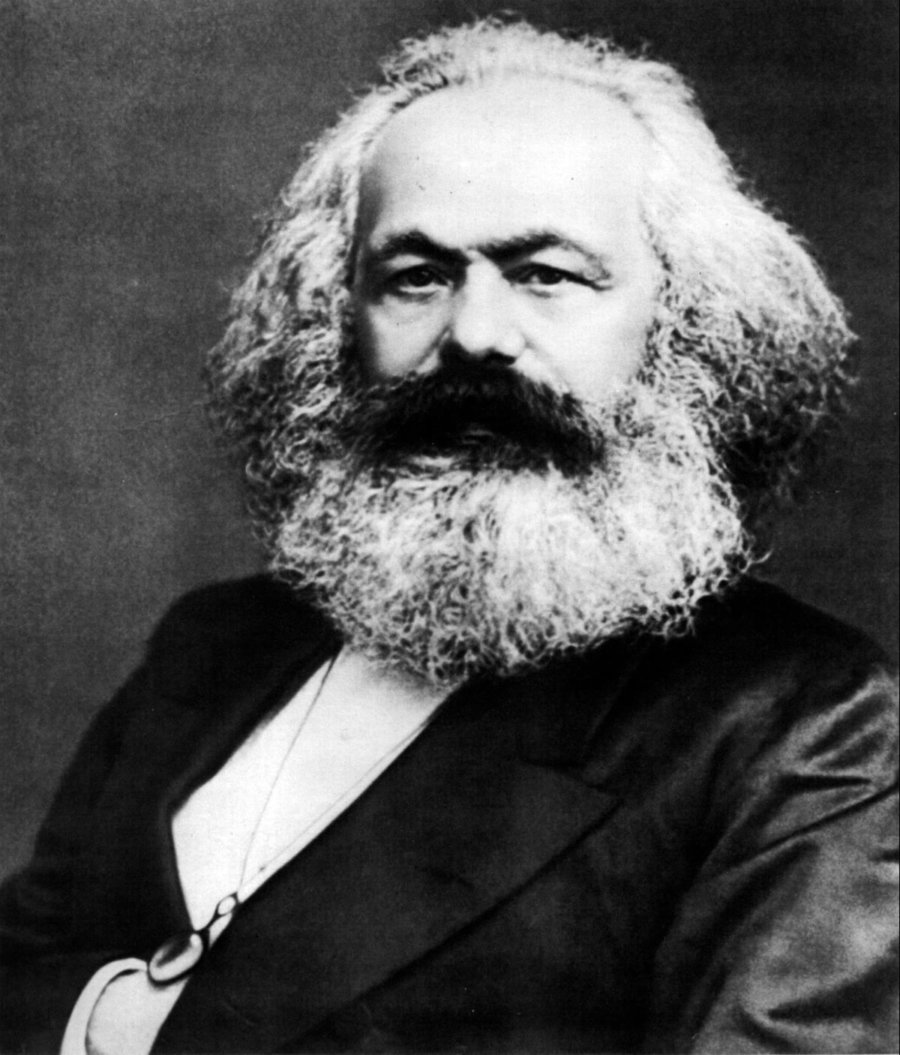

Though we evidently do not fully agree with Hegel’s doctrine about the exposure to harm that reinforces reason, it has given some good comradeship in the ideas of Marx and Engels, as seen in their Communist Manifesto from 1848, a crucial cunning of reason document, that was written not much later than Hegel formulated his ideas about it – and certainly under its direct impact. The central idea is that it takes the irritation in particular liminal moments to excite delirious effluences through producing an apparent interest in them, to excite a new course of history. They launched forth on a particular mission of evoking delirious effluences, with which a new venture, termed by them ‘Communism’ – but it can be given any other generalising name that is supposed to promote the ‘public interest’ through indiscriminate massification and universalisation – started.

The passions actuate the parties immediately interested in them, but their content is not so properly distinguishable. Passion from passion, whether noble or low, cannot be easily distinguished. They come from the senses, but can be incited and whirled up to delirium, and to restrain and withhold them is assigned to reason, otherwise they would just collide with each other. But such reason is not invoked in the Communist Manifesto, which represents a clear distortion of civilisational proportion. The authors were young enthusiasts: Marx was just about 30 and Engels only 28 at the time of its writing; just enthusiasts, as they had no proper professional background,[4] but not the less anxious to become one who is ardently absorbed in the interest of evoking emotions. To be an enthusiast had become their social vocation, and they never disappointed the expectations of those who learnt the power of effluences. They proceeded with the Hegelian doctrine of the cunning of reason, offering an uncanny version that gives unprecedented amplification for downward delirious passions, for sensuals in disorder – supposedly, in order to provide and keep order. They became enthusiasts of delirium, and the engrossing absurdity of delirium became a major history-making force for the last one and a half centuries.

Thus it happened that when the contemporary political theorist Roger Griffin situated the origin of modernism,[5] he pointed to the Communist Manifesto, saying in refuting Hegel that the dissolution of order (and not order), something that has no existence, gives rise to downward transcendentality. Hegel’s paradox in the hands of the Communist Manifesto’s young enthusiasts survived as the cunning unreason of the autonomous technological apparatus, like the feeling machine of the totalitarian state. The principle of charis as the high driving force of the society has been forgotten. Hegel’s sorcery (as coined by Voegelin, 1972) became a mere organisation technique for extracting the vital power of the deliriously vibrating soul of the people. Marx’s mind, all this time, was throwing up a succession of kaleidoscopic pictures, in which a learned eye might have recognised foreshadowed the coming fortunes of Communism, including the late and decadent descendants of the legendary revolutionaries, the lumpenproletariat, over whom he had thrown the web of witchery through suffering.

The Manifesto whispered unintelligible prophecies about the destruction of civilisation, the mental progress of the sinking proletariat, the nonexistence of property, the vanishing of individuals, the impossibility of the person, abolishing countries, nationalities, education and gender roles in mad raptures with ideas. Yet, for Marx and Engels something important has been gained by building up a new, slightly structured feeling machine. The cunning of unreason then is to transmogrify man, who has become a nothing, as he has no reality of his own to a something that has gained a shape, a ghost, a living dead; a spectre that is conjuring up the manifestation of suffering into delirious effluences. It was indeed at that the time, the mid-19th century, that necromancy, the practice of communicating, conjuring and invocation of the dead became widespread again. In the Communist Manifesto the grimness of necromancy became peppered by twinkling cunning and the dogmatism of the scientific method, resembling alchemical creative destruction: to do away with the concrete individual and the living tradition.

Can we, then, through the regulation of delirious effluences discover ourselves the same sorcery that is exerted over us, or, however modified it will be, it would remain self-annihilating? And furthermore, can we hope to find some chance clue that might conduct us to the hidden cause we seek?

The cunning of unreason (a term coined by John Dunn[6]) works through the passions that rule those effluences that flow from this dreadful state of self-annihilation. Each phase of modernity explores the sad, painful themes of voiding the properties and characteristics of the individual, through self-destruction: the absurd theme of totalitarianism; the epistemological theme of tarrying with the negative; the existential theme of nihilism; the practical theme of disease control; and the downward transcendental (a term coined by Huxley[7]) theme of nonexistence. Their outcomes are deeply pernicious and destructive, but purposefully so, as they assist the building up of a feeling machine moved by merchant logic: bringing abundance in infinite multiplication of matter that lost its concrete individuality.

Conclusion

Even though we knew it so well that autonomous technicality is our own ruin, we could not restrain ourselves, could not keep ourselves from proving to history that it was wrong. The progress of modern history eliminates the properties of the individual, its valour and dignity being nullified, its senses voided. We are obliged to confine ourselves to the introduction of only those ways which can be proven to point absolutely downward and which existed in the past only in the times of liminality. As a result, we now restrict ourselves to measures that are implausible and contain no ratio, as seen in contemporary disease prevention, that became the monstruous unreason of the state.

References

Dunn, John (2000) The Cunning of Unreason, New York: Basic Books.

Foucault, Michel (1981) ‘Omnes et Singulatim: Towards a criticism of “political reason” ‘, in S.M. McMurrin (ed.), The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Griffin, Roger (2007) Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler, London: Palgrave.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (1975) Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, ed. by H. B. Nisbet, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Huxley, Aldous (1952) The Devils of Loudun, London: Chatto & Windus.

Leibniz, Gottfried (2014) Leibniz’s Monadology (ed. Lloyd Strickland), Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [1714]

Meinecke, Friedrich (1984) Machiavellism: The Doctrine of Raison d’état and Its Place in Modern History, London: Routledge. [1924]

Voegelin, Eric (1972) ‘On Hegel: A Study in Sorcery’, in J. T. Fraser, F. Haber & G. Muller (eds.) The Study of Time, New York, NY: Springer, 418-51.

[1] In The Monadology Leibniz elaborated the feeling machine, a self-operating automaton whose structure makes it think, sense, and have perceptions, even in an enlarged size (17§.)

[2] A contemporary of Max Weber, the historian Meinecke examined the role of the State as the guardian of law. For him the State is just as dependent as any other kind of community on foreign influence and similarly unable to handle its anomalies.

[3] Hegel, the German philosopher wrote a brave doctrine in between 1822-1830, which starts Platonic and ends Christian about the paradoxical nature of reason, arguing that while reason remains forever valid and forever present, it sets passions to work through pain and sacrifices (the so-called cunning) for promoting its valid substance. The special interest in passions is thus inseparable from the active development of a general principle: for it is from the special and determinate, and especially from its negation, that the universal results. Particularity contends with its like, and so some loss is necessarily involved in the issue, warns but also consoles us Hegel, as a good modernist comrade. It implies that it is not the general idea that is implicated in opposition and combat, and that is therefore exposed to danger. No, it remains in the background, untouched and uninjured, so can be safely glorified, while the concrete aspects of our lives can be devalued with perfect justification. He called this as the cunning of reason — that reason sets the passions to work for itself, while those who develop their existence through such impulsions pay the penalty and suffer the losses. For it is the phenomenal being that is so treated, and so this part is of no value, while another part is positive and real – exclusively the part that can be connected to the universal reason. The particular for the most part is of too trifling a value, as compared with the general: individuals thus can safely be sacrificed and abandoned. The idea pays the penalty of determinate existence and of corruptibility, not from itself, but from the passions of individuals. See Hegel (1975), ‘Introduction: Reason in history’, §36.

[4] Scholars now agree that Engels had neither a university nor a high-school degree, while Marx never taught in any university, rather worked on his writings in almost total intellectual isolation. Such attitude can only be maintained by one making his own Max Stirner’s ridiculous and pathetic, but insidious ideas about ‘The Unique One’.

[5] Roger Griffin (2007) locates modernism in the Communist Manifesto, which became the springboard not only of Bolshevism and Communism but also of the fascist drive for national rebirth in the modernist bid to achieve an alternative modernity, driven by a rejection of the decadence of the ‘actually existing modernity’ under liberal democracy, still remaining too much anchored in tradition.

[6] The modern state, Dunn says, is a travesty of the system of rights which it continues to profess, and systematically distorts those rights in practice. Its politics is disagreeable and frustrating, in charade and farce (Dunn, 2000).

[7] Aldous Huxley (1952) examined the famous 17th century possession/obsession case of Urbain Grandier, a priest in the parish of Loudun, who had been found guilty of conspiring with the devil. According to Huxley downward transcendence can be highly desirable if it serves the interest of the state in order to eliminate its opponents: “But these commands are all incitements to hatred on the one hand and to blind obedience and compensatory illusion on the other. Initiated by a massive dose of herd-poison, confirmed and directed by the rhetoric of a maniac who is at the same time a Machiavellian exploiter of other men’s weakness, political “conversion” results in the creation of a new personality worse than the old and much more dangerous because wholeheartedly devoted to a party whose first aim is the liquidation of its opponents.” (1952, Appendix)