A Vulnerable Life and The Terror of History

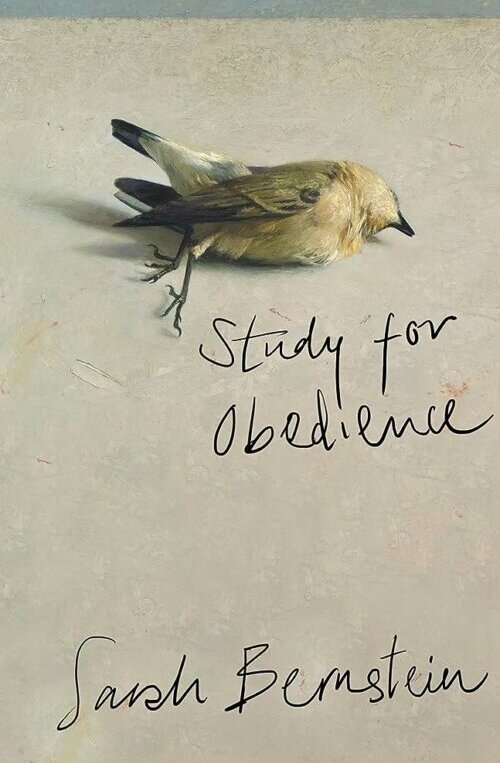

Sarah Bernstein’s 2023 novel Study for Obedience has been shortlisted by a number of literary contests, including The Booker Prize. The novel rests not on plot but on the inner musings of the narrator. The narrator is a thoughtful and mistreated woman, and her threatened dignity reaches the heart of the reader. She is a solitary, nameless figure and a nomad who desires a relationship with a village community comfortably settled in its landscape and its ways of living. The novel’s themes include exclusion and intimidation of the outsider, themes that likely are familiar to all of us through the experience of growing up or surviving the adult world of workplace politics and raising children. Because of this, the reader can easily identify with the tensions that are present throughout the novel.

There is enough wretched self-analysis and confused self-consciousness in our culture today that may spoil a reader’s first impression of the book. One must be patient while dealing with the narrator who at first desires a drone-like existence, self-denying and without depth, mechanical in her transcribing work, and utterly objectified as a sexual being. Just when we have had enough of this pathetic existence and are prepared to jettison the book, the tension emerges unexpectedly. We learn that the narrator is Jewish, and that near her brother’s country house there used to be a community of her people. As the story takes place in the late 20th century, we surmise that the villagers she is wishing to befriend were collaborators with the Nazis. Now the closed faces of the villagers, who want nothing to do with the narrator, take on an ominous power, and the narrator’s sensitive approach to the people, trying not to be intimidating or a bother to them, verges on heartbreaking.

The rich, inner dialogue of the narrator is informed precisely because she is an outsider. This pariah-like position allows her to scrutinize the dominating culture around her. In this “age of anxiety, not to say terror … soon we would not need to withdraw to the desert for a space of contemplation,” the narrator muses. Our “self-abnegation” would be guided by new reminders of our mortality and the world’s transient impermanence, reminders like mass mortality events, and news of migrations being “stopped by total annihilation.” Our world and our language are portrayed as being ungrounded, with “nothing settled in place.” And in the brand-newness of our current world was “a shadow just visible beneath its seams…the underlying ideology adapting again and again to each liberation as it presented itself.” The “world full of possibility” was suppressed by the networks of the powerful, people aligned not by love or tradition but “by virtue of their security, their salaries.” The narrator could only weep over the “beauty of a vanishing world,” where the grist mill of history had left us with hardly anything to take hold of, perhaps just “a prayer book, some scraps of song, a history lesson beginning with devastation.”

There is an understanding of history in this book that drives the character’s development. First, history is identified as a destructive power. Not only past events, but values of the past continue to divide people. The narrator understands that she was not from the village, so she “was not anything.” In another life, she and the villagers may have been friends, she reflects, but as it is, they will not deign to speak with her in a common language like English, and she realizes she is placing a burden on them when she tries to help with her volunteer work. She understands that her presence in the village reminds the people of the Jewish community that used to exist, the community that now is “only whispered about.” This reminder leads to feelings of guilt and resentment on the part of the villagers.

There is a sense that the narrator would like to overcome the burden of history. She wishes to build bridges with the villagers, not only seeking to remember their shared history, but incredibly and touchingly, to “consent to my role and responsibility” in that history. What role and responsibility could a Jewish woman have for a village that participated in the destruction of her ancestors? Most obviously, it could be a willingness to forgive them, to realize a reconciliation. On the other hand, the narrator humbles herself to such a degree, withdrawing into herself so as to “cast no shadow,” that it is also possible she is apologetic for the stress a nomadic group of Jewish people must have placed on a group of settled villagers. In either case, the narrator concludes that the burden history places on people creates a type of enslavement, making people “slaves to their ancestral hatreds” and directing their perception of life to such a degree that “the beautiful rush of the seasons” is forgotten. Old prejudices, old habits, and old relationships hide the newness and hope of a creation that is continually reborn.

History was “the resurrection to the very flesh and bone of the story of division,” and for the villagers this flesh and bone was indeed the issue “that no amount of rehabilitation could make it otherwise.” The narrator’s brother tried, and ultimately failed, to escape the pull of history. With his health failing, he tried to reach out to the villagers with whom he had been in relationship when his business successes had made him powerful and therefore respected. In his poor health, however, no one visited him or cared about him. When the narrator herself is brought to the church in order to be scrutinized by the villagers for her role in the series of mishaps harming the livestock and crops, she realizes she is meeting history directly. In her place of weakness, depending entirely on the mercy of the people of the village, she realizes that deference to the collective “was the surest and swiftest route to one’s own eradication.”

If the practice of deference endangers one’s own existence, it is obvious that one’s will, and putting on a strong front in the presence of others, is important in order to survive. This appears to be the narrator’s conclusion when she faces what for her is the “fundamental question,” that being, “whether one who escaped by accident, one who by rights should have been killed, may go on living.” In this question are elements of self-identity for the post-modern reader, who is separated from ancestors and tradition, to consider. If a person no longer belongs to a tribe with roots into a timeless past, then how can they live, and how can they see themselves rooted in a reality that continuously passes away? The narrator’s grandfather, anticipating trouble, had escaped the community before the trouble came, “but a man alone cannot make a future.” Is this the case for the rootless class of our day and age?

The will of the narrator enables her to claim her life as her own. But that will is informed by a transcendent foundation. This foundation begins with living the role of outsider where she becomes deeply sensitive of the other in contradistinction to her own mind and heart. The natural world is another source of transcendent experience for her. She walks deep into the forests, far out onto the moor, and even breaks the crust of ice on a nearby lake so she can wade into the cold waters. In the beauty of the earth, she experiences the timeless. It is here she realizes the error in putting faith in the world’s present. Our culture’s claim of the rootless present is seen as nothing more than a vain attempt at a power grab. Contemplating the ice covering the running water of a stream, she thinks that if she could be anything, “I would be that ice…always in the process of transformation.”

There are some oddities in the book that are distracting. One is that the narrator, who is obviously intelligent and has spent time in the professional world of white-collar work, is deeply superstitious. She makes talismans to ward off the evil eye, and makes figures out of dried grasses that, under the dark of night, she places on the doorsteps of every important person in the village, for their wellbeing. Is the narrator sincere, or is she intentionally provoking the villagers? Likewise, the villagers, who appear to take their Christianity seriously, are deeply superstitious in an old-world, non-Christian way. They are fearful of the narrator’s talismans, and believe her presence has brought about a series of calamities from dead piglets to potato blight. Through rituals that include lining up dead pig fetuses before the church altar, there is a disorienting sense that this story is not taking place in a world we are part of. Other oddities include the manner in which the narrator acts at times, such as pestering her brother incessantly. Is she mentally ill? Then there is the relationship the narrator has with her brother, one filled with sexual innuendo that does not seem to have any bearing on the story. Since hints of this type are never illuminated, why mention them? Is Bernstein’s character supposed to be carrying the burden of a Jewish outsider, a victim of sexual abuse, suffering from mental illness, and oppressed by office prejudices in her professional work? This is too much for one character to bear, if that is the case.

Study for Obedience is a story about a woman struggling to find her way in a world that does not care for her, and this struggle is moving. The novel may test some people’s patience, but there is much to learn from it about a person’s inner experiences as the outsider. The novel may well challenge the reader to consider who the outsider is in their day and age, and inspire a soulful scrutiny that can shed light on what dark prejudices lurk beneath their happy visage. Furthermore, when we remember Israel’s current war with Hamas, and consider the antisemitic language and action this war has spurned, it is also possible for this novel to expand one’s sensitivities of the Jewish experience post 1945.