Apparitions of the Gods: A Voegelinian Meditation

“The dove – the rood – the loaf – the wine.”

Men know the gods because they have seen or intuited them, but not all men have seen or intuited the gods, and some men are incapable of seeing or intuiting them. The gods, moreover, sometimes disguise themselves so as to test men, or they appear in and as omens and auguries, which the dull of mind and the wicked of heart invariably either miss entirely through their mental obtuseness or, through self-serving prejudice, blatantly misread.

I. The gods appear in and as their attributes, which again only those who have vested themselves in the proper lore and the requisite discipline can correctly interpret. Who would see the gods must enjoy a gift of pre-attunement, even before he bows under the discipline and engraves the lore in his heart that will let him see them. Such a man is called a poet. The ancient Boeotian teller of the gods, Hesiod, whom scholars assign to the late Eighth Century or early Seventh Century BC, bears a name that means simply “The” (he or hos) “Poet” (aiodos), suggesting that the Boeotians, or at least those of them in the vicinity of Mt. Helicon, recognized his special talent and accorded him the status owing thereto. That status may claim itself paramount because the community must commune with the gods, just as the gods must communicate with the community, and an efficient go-between nicely serves the requirement both ways. One misthinking modern school argues through Hesiod’s name that any particular poet is a non-existence, as though no one could write a poem, as though poems constituted themselves, authorless, and as though therefore no one really ever saw Hesiod’s gods or heard them speak. This thesis of a literary fantasy amounts, however, merely to another kind of noetic obtuseness. Someone wrote Hesiod’s poems, obviously, and if Hesiod were the invention of that someone then that someone nevertheless would have seen Hesiod’s gods – through his invention, as it were, and taking Hesiod’s name, but equally in a vision such that the seeing must guarantee its own authenticity and such that He remains The Poet.

In his Theogony, Hesiod sings of his own paideia. A shepherd, Hesiod one day found himself watching his flock on the slopes of Mount Helicon, where the fat soil promoted succulent clover for the grazing lambs. The Muses, daughters of Zeus, Chief of the Olympians, and of Mnemosyne, whose name means memory, appeared to Hesiod. Of divine ancestry, the Muses themselves enjoy divinity, but they are also young women who display in constant active demeanor the artistic virtues that they embody. “All of one mind” the Muses are, as Hesiod sings in Evelyn-White’s Edwardian prose; “whose hearts,” as they foot their stately sarabande in the airy altitude, “are set upon song and their spirit free from care.” Associating them with the meteoric heights, the Muses, as Hesiod recounts, have their “bright dancing places and beautiful homes” only “a little way from the topmost peak of snowy Olympus.” Being pious daughters of their father the god, they visit Zeus frequently to perform in his palace; and he takes fatherly delight in their common grace, like the paterfamilias of nine female adolescent gymnasts, who also figure in the ninth-grade Dean’s List for “A” students. The Muses’ devotions constitute a model for mortal piety, which draws its effectiveness from an admixture of beautiful execution, the fastidious performance of the rite, with the sacred intention. Hesiod praises the Muses for the punctiliousness of their ritual ablutions, their repeated self-baptism in the renewing waters, when they “have washed their tender bodies in Permessus or in the Horse’s Spring or Olmeius.” The Muses told Hesiod: “We know how to speak many false things as though they were true; but we know, when we will, to utter true things.” And they gave him a rod of laurel, the badge of his profession and the seal of his visionary credibility.

The qualities of the Muses correspond to the qualities of divinity in general, as the Greeks conceived divinity. The Muses’ choreographic routine follows a noble measure; they dance in a circle, in the natural movement of the great and forever-circling seasons; they sing in sweet tones, in melodies that flow like honey, the nourishing product of apian business. Like mead also, that fermentation of honey, their phrases flow, inspiring the poet’s tongue. The Muses have apportioned the talents among themselves, just as Zeus, their progenitor, has apportioned the cosmos among his siblings, cousins, and children; that each kinsman might receive precisely the donation that he most merits and none go improperly, or unjustly, stinted. Moira or “just apportionment” functions both as an organizing concept under the Law of Zeus and as a cosmological telos, which prompts the universe to an optimum of differentiation, with all the parts in balance, as a whole. This process runs from the original Chaos, out of which all else emerges, through the contending elemental forms, to the victory of Zeus over the insurrectionists of disorder, the lawless giants and monsters. Hesiod writes how “the dark earth resounded” when the Muses danced and “a lovely sound rose up beneath their feet.” Their dance is the sacre du printemps of archaic peasant-life that, with youthful energetic leaping, encourages the newly sown crops to grow. The Muses although virginal are connected, then, also to fertility. The dance of the Muses resembles again the activity of Themis, who, at Zeus’ behest, walks her rounds in the Olympian neighborhood by each divine street-address so as to call to order the assembly of the gods. Themis summons her neighbors so that justice, whom she represents, as blindfolded and holding the scales, might be accomplished.

Homer’s Odyssey records many apparitions of the gods and gives many indirect reports of such apparitions, some of them recounted by the gods themselves. Odyssey, Book I, opens, after Homer’s succinct invocation of his Muse, with a scene on Olympus, during the action of which, and placing the words in Zeus’ mouth, Homer furnishes his audience with a lesson in theological obtuseness. Zeus and his daughter Athene are in conversation. Zeus affirms a startling proposition – that the gods never work men as though they were marionettes, but rather that men compose their own sorrow or happiness through foresight and the quality of their acts and are therefore agents of free will – after which he provides a supporting instance. In Samuel Butler’s Victorian prose, Zeus says: “Look at Aegisthus; he must needs make love to Agamemnon’s wife unrighteously and then kill Agamemnon, though he knew it would be the death of him; for I sent Mercury to warn him not to do either of these things… Mercury told him this in all good will but he would not listen, and now he has paid for everything in full.” Mercury, or rather Hermes, in his role as Olympian messenger, is emphatically a god who appears. Like the poet, he is a go-between; he is a type of heavenly nuncio. Hermes famously beshoes himself in winged Birkenstocks, so as swiftly to fly on his numerous errands, the fletched footwear linking him with all manner of birds, whose circling flight the augurs can read. Birds resemble gods in that they are aerial, if not quite celestial, creatures. Their freedom in three dimensions exceeds that of the two-dimensional beings, who necessarily look up to them. Birds are free in the air; gods are free in the Aether, but men too are free, despite their winglessness, as Zeus himself says. Men are authors of their own happiness or misery.

The redoubtable Jane Ellen Harrison (1850 – 1928), writing in her magisterial Themis – A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion (1912; revised edition 1927), reminds her readers that while “birds are not, never were, gods,” and while “there is no definite bird-cult”; nevertheless, in the prehistoric substrate of Hellenic religiosity, “there are an infinite number of bird-sanctities.” Bird-attributes belong to many gods, not least Zeus, apart from Hermes. Consider, for example, Hermes’ sister Athene, with her pet owl. Athene, not wanting to let her brother outdo her in wardrobe, also owns a pair of flying sandals, golden no less, no doubt of the wedge-heel variety. (Knowledgeable people think of pumps in relation to Aphrodite.) Again like her brother, Athene can serve as herald of her father, the nuncia of His Will. Homer’s Odyssey, Book I, furnishes an example. Zeus heeds Athene’s plea on behalf of Odysseus, that after many delays he might be permitted at last to return home, as most of those who fought at Troy and survived already have. Her father, Athene says, should at once send Hermes to Ogygia to tell Calypso to release Odysseus from his involuntary stay, while she (that is, Athene) “will go to Ithaca, to put heart [thumos] into Ulysses’ son Telemachus.” As Butler, translating Homer, words it: “So saying she bound on her glittering golden sandals, imperishable, with which she can fly like the wind over land or sea… and down she darted from the topmost summits of Olympus, whereon forthwith she was in Ithaca, at the gateway of Ulysses’ house, disguised as a visitor, Mentes, chief of the Taphians, and she held a bronze spear in her hand.”

II. The journey is birdlike, but when once standing at the gate, Athene resumes her anthropomorphic character. Of Athene’s ornithotropy there will be more to tell, but the discussion must first attend to other features of her embassy to Ithaca. There is the matter of her disguise. All commentators on the Odyssey remark Athene’s delight in masquerade, a trait which, like her penchant for playful mensonge, she shares with her protégé Odysseus. Disguise and apparition might seem to contradict one another especially to the degree that apparition is synonymous with self-revelation. In respect of a god, however, disguise often functions as a test, to prove, for example, the perspicuity of an addressee. Homer indeed describes Athene’s advent as such a test and, in his role as psychometrist, he tallies the results. Like Aegisthus in Zeus’ example of noetic stubbornness, the Suitors who beset Odysseus’ house remain swinishly oblivious to the divine presence. The Suitors resemble the insurrectionists of disorder in Hesiod’s Theogony in that they lack reason and self-control, being creatures of savage ego and insatiable appetite. Their behavior flouts Moira or just apportionment. Telemachus, by contrast, whom Homer describes in the moment, not as eating or drinking, but as picturing in his mind the father whom he has never seen, senses an advent, not necessarily yet of a god, but of a guest, concerning whom, honoring moral responsibility, he must act with alacrity and according to strict custom.

“Telemachus saw her long before anyone else did,” Homer writes; and as soon as he “caught sight of Minerva,” then he “went straight to the gate, for he was vexed that a stranger should be kept waiting for admittance.” To Athene, Homer makes Telemachus to say, “Welcome to our house, and when you have partaken of food you shall tell us what you have come for.” The details of the ceremony replete the subsequent verses. Telemachus leads “Mentes” to a table apart from the vulgar hubbub of the squatters; he bids servants bring water for washing and wine and meat for refreshment. He carefully lodges the bronze spear in a rack set aside for that purpose. In these passages, there are in fact two divine apparitions. Not only is Athene present, disguised to be sure, but nobly disguised; yet the very ceremoniousness of Telemachus’ performance bodies forth the Law of Zeus. It is Zeus who has ordained that hosts must observe hospitality. Zeus also is present, then, in the extension of that very hospitality. Athene understands this. The fastidiousness of Odysseus’ son pleases her. She now knows – and now the reader knows, along with her – who is an honorable soul and who is hardly more than an animal, and a poorly domesticated animal at that. In an exchange, Athene, infusing Telemachus with courage, offers him an agenda of practical steps: Call the assembly, which is the same as calling for justice; commandeer a boat, recruit a company, and go reconnoitering for traces of his father in Pylos and Laconia. Athene’s departure, all at once subtle and striking, only Telemachus notices: “She flew away like a bird into the air… and [he] knew that the stranger had been a god.”

Harrison writes in Themis of ancient bird-lore, “There are many ways in which man could participate in bird-mana.” Most grossly “he could, and also ruthlessly did, eat the bird.” The Suitors busily consume meats from Odysseus’ scullery while Athene and Telemachus confer; and no doubt but some of those meats are in the form of roasted pullets. Telemachus hardly consumes Athene, but the careful reader will have remarked that she feeds him, transferring some of her courage (thumos) to him magically. Emboldened, Telemachus now undertakes what “Mentes” has suggested. He assembles the elders, something that has not happened in twenty years. The whole community is present, including the Suitors. Telemachus lodges his complaint; the squatter-in-chief Antinous, whose name means “Anti-Reason,” brutishly responds, whereupon “Jove sent two eagles from the top of the mountain, and they flew on and on with the wind, sailing side by side in their own lordly flight.” Homer arranges for Antinous to dispute the sign with Halitherses, “who was the best prophet and reader of omens among them.” Antinous having already exhibited his Aegisthus-like insensitivity to heavenly communications, everyone knows who has interpreted the signs most plausibly. “Hear me,” men of Ithaca,” Halitherses says; “and I speak more particularly to the Suitors, for I see mischief brewing for them.”

Homer offers another instance of Athene’s ornithotropy in Odyssey, Book III, when Telemachus and “Mentor,” a second disguise of the divine patroness, travel together to Pylos to consult wise old Nestor, who might have news of Odysseus. As in the previous instance, the enfolding context gives meaning to the discrete event. When “Mentor” and Telemachus first catch sight of Pylos, they see the community as a whole foregathered on the beach before the city conducting a hecatomb in honor of Poseidon. The hecatomb or bull-sacrifice is the central public rite in Homeric narrative. One feature of the rite had embarrassed Hesiod, who explained it away by means of an etiological myth that he retails in his Works and Days. The flesh-offering is supposedly for the god or gods, but in practice only the fat and bones go on the pyre to rise heavenward as the smoky meal, whereas the participants surfeit themselves at the barbecue. In Hesiod’s myth, the Titan Prometheus invented this right and endowed it on mankind, so that the stinting of Olympus falls to him, not to men, who believe themselves to be behaving with genuine formulaic piety. More importantly, perhaps, in the duration of the hecatomb, the community appears to itself fully and traffics with that other community in heaven. When Zeus is the designated object of worship, the spectacle of bull and fire might well suggest his presence. At Pylos, however, the people are offering thanks to Poseidon, who might manifest himself in the propinquity of the sea.

Approaching the foregathered demes of the city, “Mentor” and Telemachus find themselves the recipients of gracious hospitality. Nestor sends his son Peisistratus to welcome the guests. Athene, in one of Homer’s subtle jokes, finds herself making a libation to the Olympians. The guests eat and drink, but when the sun sets Athene apologizes that she must return to the ship although Telemachus will accept the invitation to sleep in the palace. Athene’s speech charms by its politeness and diplomacy, whereupon, having thus spoken, “she flew away,” as Homer pictures it, “in the form of an eagle,” taking the totemistic shape usually assumed by Zeus. Homer writes of the vanishing that “all marveled as they beheld it.” Demonstrating his discernment about things divine, Nestor tells Telemachus that “this can have been none other of those who dwell in heaven than Jove’s redoubtable daughter, the Trito-born, who shewed such favour towards your brave father among the Argives.” Grateful for the visitation, Nestor intones a prayer to Athene: “Holy queen… vouchsafe to send down thy grace upon myself, my good wife, and my children. In return, I will offer you in sacrifice a broad-browed heifer of a year old, unbroken, and never yet brought by man under the yoke.” The apparition in this case resembles the earlier one when Athene came to Ithaca. The witnesses of divinity recognize it only in the moment of its miraculous abscondment, but without any sense of loss. They then fill in the period of non-recognition such that it becomes tentative recognition, or retro-recognition, authenticated by the marvelous thrust of disparition.

The great students of Greek religiosity – Harrison, F. M. Cornford, Gilbert Murray, and latterly Walter Burkert – have all commented that later, philosophical notions about the gods find prefiguration in the theologies of Hesiod, Homer, and the other myth-poets. In the study, From Religion to Philosophy, from the same year (1912) as the first version of Harrison’s Themis, Cornford summarizes the transformation that subsumes the prefiguration. “Early science,” he writes, “seeks intelligible representation or account (logos) of the world, rather than laws of the sequence of causes and effects in time – a logos to take place of the mythos.” For Murray, however, writing in The Five Stages of Greek Religion, once again from that productive year of 1912, a scientific mood is already apparent in Hesiod’s Theogony, which attempts to rationalize the Gordian tangle of competing god-sagas, each peculiar to its isolated Greek locality, in the form of a single narrative that combines theology with emergent cosmology and appeals to everyone as plausible. In Murray’s assessment nevertheless Hesiod’s authorship “is one of the most valiant failures in literature,” a versified farrago, despite its author’s virtuosity, compounding itself from “confusion and absurdity.” It is possible constructively to disagree somewhat with Murray while at the same time affirming critically Cornford’s insight.

Consider the speculations of that most brilliant of the Ionian “physicians,” Heraclitus, whose Logos defined philosophy from his own Hellenic aeon until recent intellectually disintegrative decades. In the widely current First Fragment of Heraclitus’ literary remains, the philosopher writes how, deferring now to Haxton’s translation, “the Word [Logos] proves those first hearing it as numb to understanding as the ones who have not heard.” Note the parallelism with Hesiod’s implicit premise and Homer’s up-front thesis that some men can see the gods and interpret their comings and goings, while other men remain oblivious to the same. Note also that while any god is immortal (athnetos), the “Word” is “eternal” (aionios). The two concepts certainly verge on synonymity even though they persist in being at some slight variance with one another. The difference would be that whereas any god, like Zeus or Athene, has a biography that goes from birth to full maturity, the Logos is sans biographie. It should be added, however, that because the god’s biography excludes death, once he or she achieves full maturity, he or she will presumably persist in that state eternally thereafter. The Logos differs not altogether from a god, after all, and Heraclitus even avers in one of his aphorisms that the Logos both does and does not wish to be called by the name of Zeus.

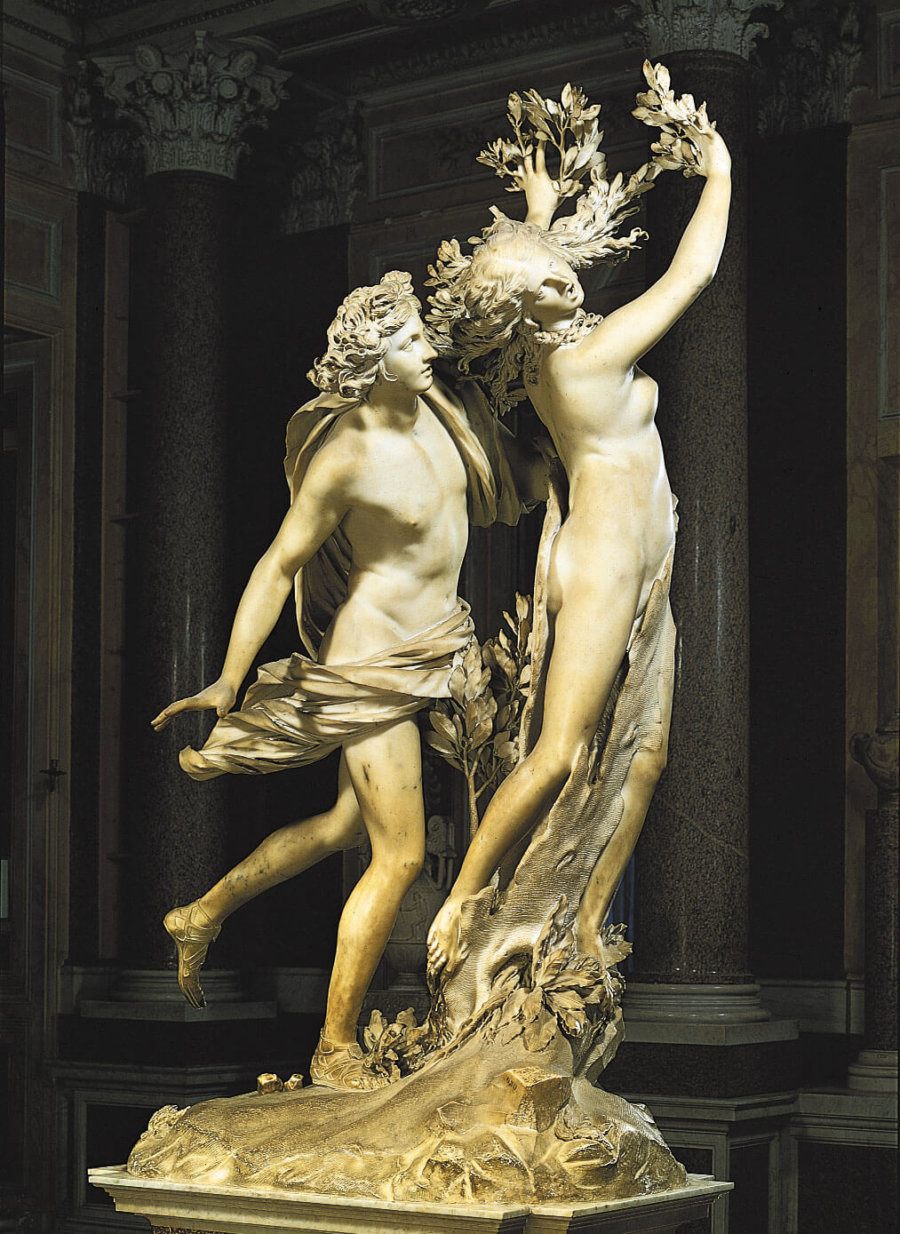

The Heraclitean Logos inclines backwards towards Olympian godhood in another way. The Logos regulates both aspects of the cosmos – the physical aspect and the moral aspect. Of the physical aspect, Heraclitus writes that, “Things keep their secrets.” This fragment often finds its translation otherwise as, “nature hides,” but nature disguises herself would be just as appropriate. The Hesiodic and Homeric gods constantly disguise themselves, sometimes by reverting to the image of the animal-totems from which, in part, they derive, sometimes by presenting themselves to mortal addressees in the image of a mortal person, as Athene does when masquerading as “Mentes” and “Mentor.” Typically, as Athene’s fluttering departures in Odyssey reveal, perspicuous men only discern the godlike presence following the departure, as a change of mood, or a sense of subtle effects, both internal and external, making the divine presence into a powerful inference. The Logos, too, is a powerful inference, more intelligible than directly perceptible by sight or sound. The transition-state, that quantum oscillation in the space-time fabric, between the last moment of the god’s human mien and his or her avian mien, which most tells of the god’s presence, moreover resists representation except in verbal description. How could a Phidias sculpt it or Artemon paint it? Harrison in Ancient Art and Ritual (1913) interprets the pose that the sculptor has given to the Apollo of the Belvedere as implying that the god is “just about to leave the earth.” In other words, it is the moment before he takes flight, transforming himself briefly into bird-shape, only then to become altogether imperceptible again. The transcendent generator of a natural pattern, a Logos, is no less an inference than a god. The prescient atoms of Epicurus are an inference – and not incidentally they have the same eternal character as a mature god or a Platonic form. Religion indeed antecedes science, as Cornford suggests; and science, until the recent disintegrative decades, absorbed the instruction in perspicuity that religion first of all provided.

III. An earlier paragraph of this essay quoted Hesiod’s description of the Muses in their aerial dance as they gaze on the proud face of Zeus their father on highest Olympus. In the image, the Muses make their appearance to Hesiod and Zeus makes his appearance to the Muses, mutually. A similar imagistic configuration occurs several centuries later in Plato’s Phaedrus, where the soul in Socrates’ elaborate metaphor is winged; and where, in straining to fly, the wing, in Benjamin Jowett’s English, “flutters.” Socrates is narrating to Phaedrus the ballistics of the soul as it ascends, during its initiation into all higher matters, towards heaven. An earthbound mentality might think that, in the intoxication of its upward rush, the soul’s highest “high” would occur on its reaching heaven. Navigating freely, however, in the stratosphere of revelation, Plato has discovered a hitherto unsuspected dimension of the cosmos. “For the immortal souls,” as Plato makes Socrates to say, “when they are at the end of their course, go out and stand upon the back of heaven, and the revolution of the spheres carries them round, and they behold the world beyond.” In this acme, the soul joins in the procession of the Olympians, “the happy gods.” Together they gaze on “the colorless and formless and intangible essence,” visible not to the senses but only to the mind, which elsewhere in Plato calls itself the Form of the Good. The panorama completes itself with these words: “And as the divine intelligence, and that of every other soul which is rightly nourished, is fed upon mind and pure knowledge, such an intelligent soul is glad at once more beholding being; and feeding on the sight of truth is replenished, until the revolution of the worlds brings her round again to the same place.”

Elements of the Hesiodic picture find expression at a higher level in Plato’s magnificent tableau, but so too do features from Homer. In Theogony, the Muses dance in a circle; in Phaedrus, the cosmos rotates on its axis. The terpsichore in Hesiod has to do with the cycle of the seasons, and the cycle of the seasons, culminating in the harvest, has to do with the greatest of existential needs – food for the communal belly. The terpsichore in Plato also corresponds to a cycle of seasons, which takes the form of the cosmic curriculum of psychic renewal. Note, however, that Plato employs the bodily metaphor of nourishment in order to convey the effect on the soul of its gazing on the intangible essence. The metaphor recalls the effect that Athene exerts on Telemachus when she visits him in Ithaca. Athene is ornithotropic, but so is Plato’s soul. Birds have mana, as Harrison asserts. It would be Polyphemus-like for Telemachus to eat his guest, even though he wants for mana, but the goddess solves the problem by feeding her host. A hearty meal, like the Thanksgiving-Day turkey-feast, both replenishes its consumer, so that he might fast over the next few days while working with renewed energy, and induces an immediate tryptophan-ecstasy. The mere sight of a drumstick in the days after can recall the cenobite to that ecstasy, if diminishingly – people say. In Plato’s scheme, any sight of beauty reminds the initiate of his glimpse of the Absolute, but reminding is indirect, not immediate, such that the Intangible Essence almost always exhibits the character of a Deus Absconditus.

The transition from the bright outre-ciel of Plato’s Phaedrus to the gloomy Niflheim of Snorri Sturluson’s Edda precipitates the subject steeply, to be sure, but the perpetually beclouded Goths saw their gods as frequently as did their Greek cousins away in the sunny south (Muspell) – and a gust of cold air might very well be refreshing. The Scandinavian dom, in English doom, or “judgment” is nevertheless the same etymologically as the Greek Themis. A slightly obscure member of the Aesir, Tiwaz, later known as Tyr, who generously lends his original name to Tuesday, is the same etymologically as Zeus. And Norsemen call Titans Jotuns – exactly the same name. In “Gylfaginning,” the first section of Edda, Odin, appearing in disguise to Gylfi as Hár or “the High One,” even knows of a heaven above heaven and of a heaven above that heaven, as if to outdo Plato. Odin likes to disguise himself; he suffers wanderlust and often absents himself from Valhalla. The Edda knows two suspiciously similar gods, Óðinn or Odin and the rather more obscure Óðr. Óðinn is grammatically no more than Óðr with the nominative marker –r replaced by the definite article inn, in the attached position. What is Óðr that Óðinn be the definitive instance of it? Óðr derives from the Proto-Indo-European stem wāt, meaning “to inspire,” and stands in generative relation to a slew of words that imply consciousness and mood – thus the Latin vates or “seer,” the Anglo-Saxon wóð or “song,” the Sanskrit véda or “knowledge,” and even the Old West Norse Edda, which like véda suggests “knowledge” and like wóð suggests “ode,” as in the song of the aiodos, or “saga,” or “lore.”

Nordic lore links Odin to esoteric knowledge and to transcendent states of mind, making him oddly similar to Athene, whose attribute, the spear, he shares and who, again like her, is ornithotropic, usually as a raven but sometimes also as an eagle. Famously Odin descended into Niflheim to the roots of the world tree Yggdrasil either to drink from the dwarf Mime’s well or to read Mime’s secret runes. Mime extracted the price that Odin should give up his left eye and hang nine days nailed to the tree, his side penetrated by a spear. “Veit ek at ek hekk” as the Elder Edda makes Odin to say, in runic verse – “Know I that I hung,” that is, with the emphasis precisely on knowing. The scenario strongly suggests shamanistic initiation. H. R. Ellis Davidson remarks in Scandinavian Mythology (1969), “Learning and wisdom were held to be gifts from Odin.” Davidson affirms that, in his ordeal, “Odin underwent something which closely resembles the visionary experience of death and resurrection endured by the shamans of Siberia.” In his intellectual character, Odin differs markedly from Thor, who is basically a muscle-man like Hercules. In Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, Wotan, the German Odin, over-thinks everything, his virtue having become a vice. When Odin puts in an appearance in myth and saga, however, he often does so to impart knowledge or to test a party with the aim of increasing the party’s discipline, a teleological pattern similar to that in the Athene-Telemachus subplot in Odyssey.

In The Saga of the Volsungs, having sired the Volsung clan and wishing to provoke the ambition of his son Sigmund, Odin arranges a trial. In Chapter 3 King Volsung prepares a wedding-feast for his daughter in his mead-hall. In the middle of the mead-hall grows a tree called Branstock. In Jessie Byock’s translation the saga-writer describes how “a man came into the hall… not known to the men by sight,” who was wearing “a mottled cap that was hooded” and “linen breeches tied around his legs.” This man, “very tall and grey with age,” who “had only one eye,” plunged a sword up to its hilt in Branstock. He then spoke these words: “He who draws this sword out of the trunk shall receive it from me as a gift, and he himself shall prove that he has never carried a better sword than this one.” The saga-writer never once invokes the name of Odin, but in supplying his attributes, he identifies him indirectly. It is almost as though a taboo prevented the invocation of the god’s name. In Chapter 8, Sigmund in a fury has wounded his son Sinfjolti by biting his throat. Sigmund sees two weasels. One weasel bites the other’s throat; the assailant weasel retrieves a leaf from the nearby forest and, applying it to the wounded throat, heals his victim. According to the saga, “Sigmund went out and saw a raven with a leaf”; whereupon “the raven brought the leaf to Sigmund, who drew it over Sinfjolti’s wound” and cured him. Odin appears perhaps both as the two weasels and as the raven.

Odin appears again in The Saga of the Volsungs, Chapter 13. One day, wandering in the forest seeking a steed, Sigurd, Sigmund’s son and Odin’s grandson, encounters “an old man with a long beard,” and “this man was unknown to Sigurd.” The old man advises Sigurd on how to acquire the best steed, whereupon “the man disappeared.” In addition to traveling entirely incognito, Odin also reserves a bevy of pseudonyms. In Chapter 17, Sigurd is leading a fleet of ships on a Viking raid against the sons of Hunding. Manifesting himself simply as “a man,” Odin recites a litany of his noms de déguise: “As Hnikar they hailed me, / When Hugin I gladdened, / And then, O young Volsung, / I vanquished. // Now you may address / The old man of this rock / As Feng or Fjolnir. / From here I would take passage.” A moment later, the skald indicts, “Fjolnir disappeared.” In Fjolnir, Odin takes the name of a legendary Swedish king, the founder of the Yngling dynasty, whose death, much envied in Ireland, and in parts of Massachusetts, came when he drowned in a vat of mead. One of the stories told of Odin is how he won the Jotun Kvasir’s mead, a task that he accomplished in the form of an eagle. According to Davidson, Kvasir’s mead imparts to him who drinks it “the power to compose poetry, or to speak words of wisdom.” Kvasir hardly qualifies as a personal name even though the story personifies it in the figure of the giant; rather, it refers to fermented berry-juice, the vin or wine of the ancient North. Wings, intoxication, and vision: If these episodes of Odin seemed like le grand bouffe sauvage, they would nevertheless not be that far from the episode of the Platonic soul in its ascent, which experiences its own refined óðr, or inspiration, high up in the Aether.

Odin signifies himself not so much by appearing as by disappearing, much as does Athene, in her withdrawing flutter of feathers. Odin kept appearing and disappearing even when Christianity came to the North. The troubling chief proselyte of the Viking world, King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, had at least one meeting with the All-Father. According to Olaf Tryggvason’s Saga, Chapter 71 (Hearn and Storm’s translation): “It is related that once upon a time King Olaf was at a feast at… Ogvaldsnes, and one eventide there came to him an old man very gifted in words, and with a broad-brimmed hat upon his head. He was one-eyed, and had something to tell of every land.” Olaf finds the old man’s stories fascinating and asks for another one as soon as the previous one has come to its end. Finally, late at night, and at the behest of the bishop, the old man takes his leave. On waking, Olaf still hungers for lore. He asks after the old man, “but the guest was not to be found.” It seems nevertheless that before he vanished, the old man visited the cooks in the kitchen, where he observed how “they were cooking very poor meat for the king’s table.” He then produced “two thick and fat pieces of beef, which they boiled with the rest of the meat.” Suspecting mischief, Olaf ordered the cook to throw away all the meat. “This man can be no other than Odin whom the heathens have so long worshipped,” said; “but never shall Odin beguile us.”

In the Christian era, the taboo against naming Odin by his name, like the god himself, has disappeared, but Odin functions as always: He nourishes intellectually, arousing the king’s appetite for lore, as well as nourishing, or attempting to nourish, in the gourmandizing way, with a fine boiled breakfast. That Olaf achieves a higher state of consciousness than is normal for him while listening to Odin, his reluctance to sleep attests, and so does the immediate renewal of his curiosity on his awakening. Olaf declares Odin suspect, but the tale gives no evidence of any scheming or misdemeanor. Odin has been generous, providing the two large beefsteaks. He has precisely not deceived anyone, least of all the king, but has contributed to his wisdom. No such numinous appearances as this one accompany Olaf’s conversion to Christ, which is at least a decade past when he confers with Odin. A hermit predicts Olaf’s future and the future in becoming the present affirms the prediction. Olaf takes it as a cue to convert, but nothing like an epiphany happens. How far Olaf understood the Christianity he elected is a legitimate question. Not very far. His program of forcible conversion employing hideous torture makes him more of a berserker than a saint although he is indeed called Saint Olaf. His campaign to Christianize Norway includes no epiphany either, just extravagant bloodletting in the manner of Grand Guignol. Not so much as a dove descends earthward from the heavens, a peaceable dove. On the other hand, Olaf makes a point of desecrating heathen images, as he does exemplarily in the Temple of Thor at Trondheim.

IV. In terms of his Noetic Perspicuity Quotient or NPQ, Olaf stands immensely disadvantaged before Hesiod, who could hear the Muses sing, and before Telemachus, who in Odyssey knows that it is Athene who has just bid him adieu in a rush of delicate bird-flight. As to Aegisthus in Zeus’ little story to Athene in Odyssey, Book I, so too to Olaf a god appeared. Olaf refused to integrate the experience, lapsing back into his average low degree of pseudo-Christian stupidity. Like Aegisthus, Olaf came to a bad end, drowning at sea during a naval battle although certain parties claimed to have seen him later in Rome or Jerusalem, supposing therein his survival or miraculous return. Naturally, no one has visions of Olaf today and neither of Athene or Zeus. Liberal-modern people only see themselves in the selfies that they constantly snap. Neopaganisms like Asatru or the Burning Man Festival amount to so much costume-play and differ hardly at all from casual atheism. The average NPQ-level of the early Twenty-First Century is quite low compared to that of the Archaic Period in Greece or the Pre-Christian Early Middle Ages in Scandinavia. Instead, the examiner of the current scene will see the ubiquity of Advanced Antinous Syndrome, which correlates to an NPQ-level so low that it constitutes a type of Noetic Perspicuity Retardation or NPR. The most severe cases of NPR occur in the most institutionalized segments of the society among the self-denominating elite classes. Never shall Odin beguile them much less the Form of the Good, but what they mistake for their sophistication is nothing more than the sloganeering of their grande bouffe sauvage. The phenomenon, longstanding, is coeval with so-called Enlightenment since the Eighteenth Century.

For this reason Eric Voegelin (1901 – 1985) found it necessary, as late as the last year of his life, to vindicate the truth that he perceived, not only in Plato, but in Hesiod and in myth and speculation. In the final volume of Order and History, the posthumously published In Search of Order (1987), Voegelin conducts an in-depth analysis of Hesiod’s symbolism. The Muse-function interests Voegelin particularly. A high-NPQ person, Voegelin observes that the Muses “mediate divinity primarily to the gods themselves, and only secondarily to men by inspiring the ordering word of princes and singers.” Why should this be so? Voegelin answers that while the gods are immortal they are also living and as living beings they are liable to forgetfulness. Voegelin notices Hesiod’s peculiar usage of the Greek verb to remember. It should be translated, he argues, as to be remembered. “The Olympians,” Voegelin writes, “have to be remembered of their existence as a presence of the divine order, victorious over the disorder of the older gods from whom they stem and who are still alive.” Memory establishes the foundation of consciousness, which constitutes itself as a dynamic, not as a static field. The gods as a group are an element in the field of consciousness, as are human beings. The gods signify a “Beyond” in Voegelin’s term that insists on being symbolized in the earliest known strata of mytho-speculation, but which is subject at key moments to further articulation.

Voegelin writes that, “Remembrance, in the sense of the Hesiodic symbol, does not recollect a dead past but ‘remembers’ a presence that is a living presence only if it is fully conscious of its ordering victory over forces that once were just as victoriously present.” Everything conscious must remember itself at every moment or it ceases to be. Consciousness constitutes itself in a continuity that emerges from the incalculable past and destines itself into an incalculable future; it therefore transcends, just as it grips and shapes, the individual. That knowing is remembering is a Platonic precept, but what the subject remembers and thus also knows comes in large part from before his acquisition of personal self-awareness, in the form of a moving, living, collective memory-cum-awareness. “Understanding [Hesiod’s] ambiguous symbolism historically,” Voegelin argues, “does not mean establishing it as a dead object on a point of the time-line, an antique as it were to be preserved for its ornamental value; it means, rather, to participate in its living presence as an event in the quest for truth.” Voegelin cites Hesiod’s “noetic effort in openness to the Beyond.” Openness permits participation. The opposite of openness leads to alienation, dullness, and resentment, chief characteristics of the low-NPQ or NPR person. With what might one usefully contrast Voegelin’s high-NPQ openness to Hesiod?

Could any document be more wooden, could any document exhibit less openness than one of those more-pious-than-thou lectures by that saint of self-righteous liberalism Bertrand Russell? “Why I am not a Christian” (1927), which should really be called “Why God Cannot Exist,” is exemplary, but before assessing it, it would be wise to quote another occasional document by Russell from two years later, “How I Came by My Creed.” In “My Creed” Russell recounts autobiographically how, in his teenage years, he systematically disencumbered himself of all traditional certainties. “The first dogma which I came to disbelieve,” he writes, “was that of free will.” Given that “all motions of matter were determined by the laws of dynamics” they “could not therefore be influenced by the human will,” as Russell reasoned it out in his own mind. Next Russell rid himself of any faith in “immortality,” presumably meaning immortality of the soul; and next after that of any belief in God. The first riddance and the third go together. Outside Monophysitism, Mohammedanism, Socialism, and the Aztec Pyramid-Cult, men recognize the gods and free will as concomitant. The gods guarantee free will by not standing in the way of human stupidity. In Odyssey, Book I, which an earlier paragraph in this essay quotes, Zeus reminds Athene that men possess free will and therefore author their own happiness or misery, with which process the gods never interfere. Most grimly, however, Russell, in asserting universal material determinism, with its denial of free will, abolishes any persuasiveness that might inhere in his own assertions, which he, being a mere particle in the deterministic current, could not in fact have conceived, and which could carry no meaning. Yet Russell appears oblivious to his having consigned himself to oblivion, which is about as low on the NPQ-scale as a thinker can lower himself. What about “Why I am not a Christian”? “Fasten your seatbelts,” as Bette Davis says in All about Eve; “it’s going to be a bumpy ride.” And it will be downhill into immaculate subscendence.

The backbone rhetorical scheme of “Why I am not a Christian” consists in a series of purported refutations of traditional arguments for God, or as Russell puts it with liberal inelegance, “the existence of God.” Liberals erroneously apply the category of existence to God, who being eternal rather than existing just is, quite as the axioms of logic and the fundamentals of revelation just are. Russell wishes to abolish the argument that the world requires a First Cause – that is to say, a Creator. “There is no reason,” he writes, “why the world should have come into being without a cause; nor, on the other hand, is there any reason why it should not always have existed.” Note the confusing triple-negative: “No reason,” “not,” and “without a cause.” But in that case, there would equally be no reason why the world should not have come into being with a cause, a proposition that requires only two negations. Russell, who ought to have known about Occam’s razor, gives no indication why one possibility should be preferred above the other, nor does he display any curiosity about the more possible possibility that he so prejudicially rejects. In the next sentence, Russell asserts that, “there is no reason to suppose that the world had a beginning at all,” the absurdity of which one can easily perceive in hindsight. It is ironic that Russell, the great apostle of the rational, scientific order should have been so contradicted in subsequent decades by science, not least by the observed expansion of the universe. Edwin Hubble had in fact measured that expansion as early as 1922, five years before Russell published his lecture. It would be pleasant to shout back at Russell how wrongheaded he was, but a nod is only as good as a wink to a blind bat.

Turning to the traditional inference of Nature’s God from the design implicit in Nature, Russell writes: “There is, as we all know, a law that if you throw dice you will get double sixes only about once in thirty-six times, and we do not regard that as evidence that the fall of the dice is regulated by design; on the contrary, if the double sixes came every time we should think that there was design.” Russell packs so much cognitive manure into that sentence that unpacking it just about equals one of the Herculean tasks. Russell asserts the non-intentionality of the cosmos, but in order to do so, he must employ instances of intentionality. For example, before anyone could throw a pair of dice, someone had to conceive the idea of a pair of dice and then manufacture it. The dice never throw themselves. Someone must intend to throw them, such that an idea stands behind the act. The behavior of the dice – double sixes only once on average in every thirty-six casts – far from disproving the orderliness of the cosmos affirms the subtlety of that orderliness. More than that, however, the uncertainty in outcomes opens the way for free will by demonstrating precisely that whatever the cosmos is, it is not an all-determining mechanism. Thus when Russell writes that “the whole conception of God is a conception derived from the ancient Oriental despotisms,” it becomes brilliantly clear that he has no bloody idea what he is talking about.

Men know the gods because they have seen or intuited them, but not all men have seen or intuited the gods, and some men are incapable of seeing or intuiting them. The gods, moreover, sometimes disguise themselves so as to test men, or they appear in and as omens and auguries, which the dull of mind and the wicked of heart invariably either miss entirely through their mental obtuseness or, through self-serving prejudice, blatantly misread. Russell might stand for Richard Dawkins, S. T. Joshi, Sam Harris, or Daniel Dennett for they share his extremely low NPQ. In the contemporary phase of the modern world, noetic obtuseness rages like a pandemic. One sign of the prevailing spiritual retardation is that all doctors of philosophy in the humanities – using that phrase “the humanities” loosely – have heard of Bertrand Russell and quite a few in the course of their studies will have read snatches, at least, from “Why I am not a Christian,” but none will ever have heard of, much less have read, Eric Voegelin. Modern doctors of philosophy in the humanities will certainly have heard the names Dawkins, Joshi, Harris, and Dennett, and some will even have read excerpts from their books. None will have heard of, much less have read, Jane Harrison. Dennett manages to outdo Russell, a difficult thing to accomplish. Dennett declares that not only God but also consciousness itself is an illusion – which Russell implicitly argues in “My Creed” without however grasping that that is what he is doing – but then Dennett keeps talking, as though flapping his jaw could have meaning. There is more meaning, to be sure, in the flapping of a jackdaw’s wing. There is more meaning in the flight of birds. God-deniers like Russell, Dawkins, Dennett and their followers, the ultra-sophisticated ceaselessly deconstructing doctorate-holders, like to say that they put their faith in man, not in God, but the only possible subject of faith in man is God. As Rémi Brague remarks in his recent book On the God of the Christians (2013), God never demands faith, for that would be to destroy faith. God asks of us one thing: That when He appears in the bread and the wine we eat him.