Belief vs Knowledge and Plato’s Tripartite Soul

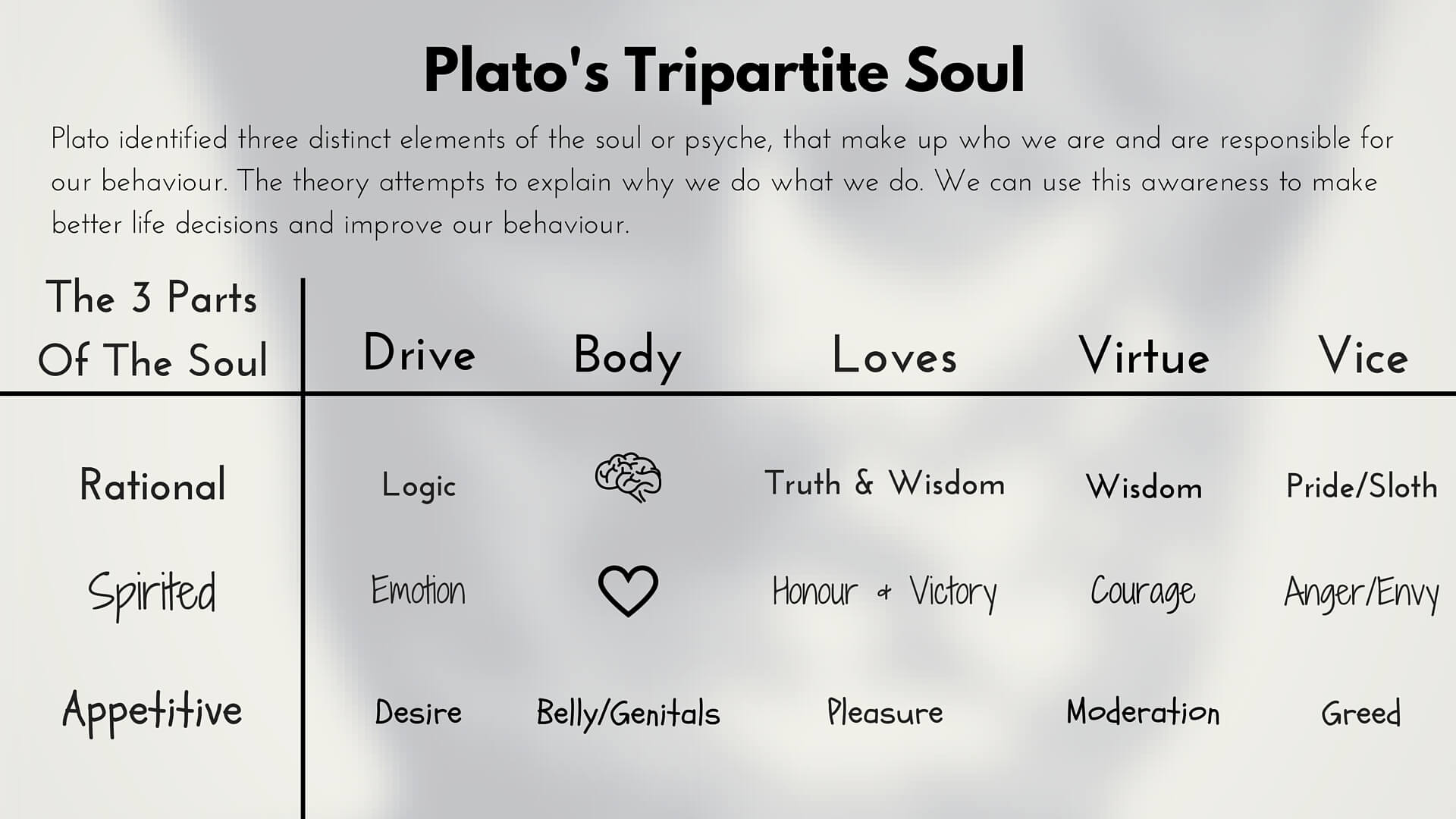

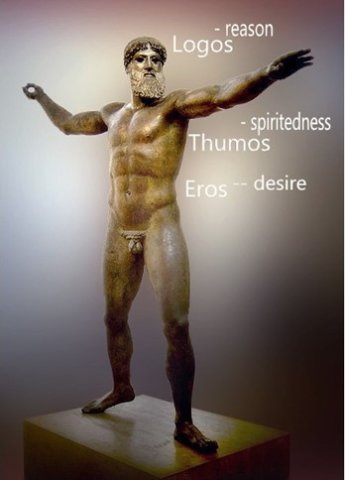

Plato suggested that if a person were to be cut open a homunculus,[1] a lion and a many-headed beast would be revealed. These creatures represent the three different kinds of soul (psyche) out of which someone is composed. In Greek they are Logos, Thumos, and Epithumia.

Logos (reason) is symbolized by a little person.

Thumos (gumption, spiritedness): a lion.

Thumos (gumption, spiritedness): a lion.

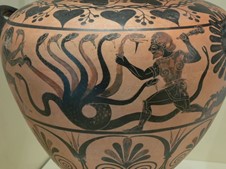

Epithumia (desire, appetite): a many-headed beast.

Plato argues that just one of these creatures can be the master, while the rest are its slaves. In most people, Epithumia is king. In that case, someone uses all his intelligence and all his drive, persistence and gumption, to satisfy the least intelligent part of himself – random, blind, desire. The symbolism of the many-headed beast is that, like the mythical hydra, should you cut off one head, another two grow in its place. Raw, undirected desire is insatiable.

We could add that most of our desires we get by imitating other people. They want a car, spouse, job, house, garden, two children and a dog and we want the same thing. If you were to go to college only to find everyone had decided college was not for them and you were the only student, how long would you continue wanting to be a student? If the Wimbledon trophy could belong to whomever wanted it, and no one wanted it, would you want it? There is no great mystery here. We imitate other people in just about every other aspect too – the way they dress, cut their hair, wear their shoes, walk, throw a baseball, write an email, address each other, sit rather than crouching in a chair, modulate the loudness of their speech, the way they are behaving towards you, move their arms, where they direct their gaze in social situations, ad infinitum. Desires are just one aspect of our mimetic nature.

Because trying to satisfy every whim is expensive, most people are obsessed with money, Plato thought. And what they care to purchase with that money is pleasure. At the Olympic games, these people would be the vendors selling drinks and food to the spectators and athletes. They go to make money.

The rather distant second most popular master of the soul is Thumos. Associated with the chest, heart, and feelings, Thumos is the drive to overcome obstacles. Athletes and soldiers are dominated by this part and their aim is honor, and their virtue is courage. All their intelligence will be employed to gain honor – to win the race, the wrestling match, or to distinguish themselves in battle. And they will satisfy only those desires that are consistent with their chief aim.

Such aims are not terrible, but Aristotle, Boethius, and others pointed out that honor is too dependent on other people’s opinion of you, which can be fickle. And the smartest part of a person is still subordinate to its inferior. Obviously, such a person will be among the contestants at the games.

Finally, only a very few, the lovers of wisdom, the philosophers, have their souls in the proper order with Logos mastering gumption and desire. Reason will choose only those desires to satisfy that seem most likely to promote human flourishing and gumption will be employed in satisfying those carefully selected goals. At the Olympic games, the philosopher is symbolized by the spectators who are there merely to observe. They are not hoping to make money, nor are they hoping to have honor conferred upon them by their victory. They are impartial, disinterested and exercised only in contemplation. Contemplation is what gives them their primary joy.

Plato’s account of the human soul can help explain the difference between knowing something and truly believing it.

It is impossible to define knowledge in terms of its necessary and sufficient conditions. Every definition philosophers have attempted excludes some instances of knowledge, or includes things that are not knowledge at all. However, we need the concept of knowledge and it is not going anywhere. We cannot define beauty either, but beauty does not cease to exist or to be an important part of human life.

It seems that for proper knowledge and belief the head and the heart must cooperate. Knowledge with Logos seems to involve intellectual assent, but without the participation of Thumos and emotion, that assent is empty and does not drive action, and thus could be said not to constitute real knowledge at all.

Judge a person by what he does, not what he says. Someone with a phobia of flying “knows” in some bare, intellectual sense that flying is really very safe but he might resist like crazy if you attempt to shove him aboard a plane. His head says one thing and his heart another. It could be said that he does not really “know” planes are safe at all.

Someone might read that earning anything over seventy-five thousand dollars a year does not contribute further to one’s happiness, but his heart might not agree – despite being unable to present evidence to the contrary.

Real belief and knowledge seem to require at least two different aspects of the human soul, Logos and Thumos, working together. This might explain the otherwise very odd-sounding statement that Plato has the character of Socrates say, namely, “To know the good is to do the good.” The obvious response is that we know what the right thing to do is and do the opposite all the time. Socrates could respond that a person does not really know what is good for him if he does not act in concert with that knowledge. The man says he knows he should exercise more, but when we see him continue to sit unbudging on the couch, we can see what he really thinks will make him happier.

Plato suggests that we all want to be happy (flourish) and we consider good anything that we think will contribute to this happiness. However, very often we are wrong. There are all sorts of illusions and things that seem more appealing than those items which will actually make us happy.

Your head tells you to study for the quiz, but your heart says the joys of cellphones are better. You do not really know that studying is consistent with “the good” at all. No more than the flight phobic person trusts airplanes.

One way to put this is that often we do not show concern for our future selves. We feel no compassion for that yet-to-exist jerk as he flails around trying to answer the quiz questions he never studied for.

“To know the good is to do the good” could perhaps by restated “to know fully the good is to do the good.”

The need for heart and head to cooperate in epistemology is likely to be ignored by most modern philosophers since they are too in love with syllogisms, logic, and rationalism. Emotions are viewed with suspicion. Emotions are hard to write about or analyze because they are not conceptual or logical. They are not thinking, though a lot of thinking does not work properly without their input. And analytic philosophers are notorious for not worrying about the connection between living one’s life and philosophizing. As a group, they do not care about wisdom anymore and thus they do not care if their philosophy is consistent with the way they are actually living their lives, and so they do not concern themselves with whether a person is saying one thing and doing another. The saying part – the bare intellectual assent – is quite enough for them.

Postscript

I was in my mid-thirties before I belatedly had the insight that our weaknesses are likely to seem ridiculous to other people if they do not share them. Sometimes when we hear what someone is afraid of we think “That’s stupid! That’s not scary at all!”

Just how irrational this tendency is seemed particularly clear in a podcast where someone with a fear of flying was interviewed. The woman described going to a class for people with this phobia. The instructor asked people to describe what it was precisely about flying that terrified them. One person said that she was afraid the wings might fall off. The woman describing the scene expressed the utmost scorn and contempt for this fear. Doesn’t she know that planes are designed in such a way that their wings do not fall off? What an idiot! “Well,” the podcast interviewer asked, “what are you afraid of?” “Why, turbulence, of course. That is what is scary about flying.” But, of course, turbulence is also something that plane designers are aware of and turbulence presents no particular dangers either.

This shows that if someone shares your fears, but not precisely as you perceive the threats to be, then even then we tend to be unsympathetic and contemptuous.

In the spirit of reciprocity, of doing unto others as we would have them do unto us, then we should make an effort to be charitable and forgiving of other people’s fears, as we hope they are charitable towards us. We often do not realize that this is necessary because our own fears tend to seem perfectly reasonable and understandable to us, but there is a good chance they will not seem that way to others.

Notes

[1] A little person.