With Borges Through Wyoming

In early summer 1976, we took a train from Oakland California to Detroit, a trip lasting a couple of days. It was a time of stress and doubt, but of course one could say that about the whole decade. Even in 1976 such a trip by train was less a matter of travel than tourism. As now, if you needed to get somewhere, you took the plane, if you could afford it, or a car or a bus, if you could not.

There is in fact a contemplative element to train travel. You are connected with earth, as you are not with a plane, and yet trains travel alone, rather than with a crowd of other vehicles, as on a highway. On a train you pass through the backyards of the world.

Among the equipage for the trip was a bottle of hootch picked up in a hurry at the last moment from a small store near the Oakland train station, and a number of paperback books.

We pointed out to the clerk in the liquor store a bottle of what we thought was Brandy and Benedictine (the young and semi-learned often have a sweet tooth in these matters). We didn’t check the bottle; that part of Oakland (a fine city and a serious port) was such that someone with baggage didn’t linger.

Where the paperbacks came from, who knows? They must have been picked up at random from one of Berkeley’s many used bookstores.

After the novelty of the train itself had worn off, somewhere to the east of the mountains, we unpacked the bottle and discovered we had bought straight brandy (not at all sweet). Well, no help for that. We picked up the first paperback, more or less at random.

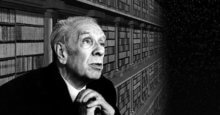

This was Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges, an author completely unknown to us. Never mind. Borges, whoever he was, would do.

Now at this point, the trip took an abrupt change in tone.

Most of our readers will have come across Borges in reviews, or in class. We appeal to those readers to imagine the shock of meeting this author cold and from a point of utter ignorance. Imagine reading “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” without knowing what you were getting. Imagine discovering Pierre Menard without being in on the joke that he was as fictional as his ambitions.

Here was, here was indeed, something completely different. It was a “what-the-hell” moment, if ever there was one.

A close friend reports much the same experience upon watching on television, unprepared, “Unfaithfully Yours,” the Preston Sturges classic. She reports that it was unsettling, largely because it was unclear that the intent of the film was comedy.

The rest of the trip developed a routine: one short story, followed by a shot from the brandy. And so we proceeded across the Western United States. By the time we got to Detroit Union Station (a very spooky place even then) we were Borgians forever.

Now this is charming & all, but here’s the nub.

Over the years, many years, since then we have read a lot of Borges–fiction, poetry, and non-fiction. But in our recollection, the author is always tied in with the train, and its particular rhythm, and the landscapes through which we travelled, and especially with Elk Mountain, a lovely medium-sized peak in Wyoming, which we saw, across the low prairie hills going past at dusk one night while standing on the back porch of our railway coach. There was a sense of quiet and infinite space to that evening, and it is mixed in with Borges, a most detached author.

Perhaps he would have been pleased: he was a city man who had a yearning for non-city environments–the pampas of Argentina in particularly, but not exclusively:

Aquí también. Aquí, como en el otro

Confín del continente, el infinito

Campo en que muere solitario el grito;

from “Texas”

[Here too. Here as at the other edge / of the hemisphere, an endless plain / Where a man’s cry dies a lonely death . . . Mark Strand]

This suggests to us a topic of meditation that might be amusing, and even a little edifying.

Let us assume that many people have in their minds a sort of core personal library: a dozen books at most, not all serious and grave, but all of which have echoed through their whole lives.

Often this includes a couple of children’s books, some major novels (Tolstoy-class literary battleships) and often a single item read in early adolescence and no more forgotten than what a native American boy sees during his vision quest.

Would it not be piquant first to list these to oneself and then to recollect, as best as one could, the circumstances–time and place–when they were first read?

Is Tolstoy your Huckleberry? Excellent. Where did you meet Tolstoy?

Is Dostoyevsky the author who drove an axe through the ice of your indifference? Where did you first read Crime and Punishment? What year? Who were you then?

Where were you when you first read Voegelin?

If you carry the world of Jim Thompson on that shelf of your mental library where books are within arm’s reach, where did you first read The Getaway–one of the nightmare classics of the 20th century and as unsettling as Lovecraft.

When we think about a book, Treasure Island, the book itself is the main point, which goes as understood. The text is the substance, if you will.

But a book is not actualized until it is read. Who reads, where, and when, come into that actualization and might be usefully pondered.

If we wanted to break an aesthetic butterfly on a metaphysical wheel, we might play with the idea that the reader is in fact part of the circumstances involved in the actual reading–as if one imagined that it was not so much a reader on a train who read this or that book, but that the encounter was between the book and the circumstances–as if something of the train itself was turning the pages.

Even treating that as a fancy, might not this topic of meditation be pleasurable, and perhaps the seed around which other thought crystallizes? Look what Proust got out of that cookie.

Or, it might work as encouragement, at least, to keep a reading diary. What better device to re-awaken the wonder that we experienced when we read those books, whatever they might be, that turned out, sometimes to our surprise, to matter.

The trip also shifted our tastes in booze several notches toward the dry, to our surprise.

Good-bye Youth and Cherry Brandy.