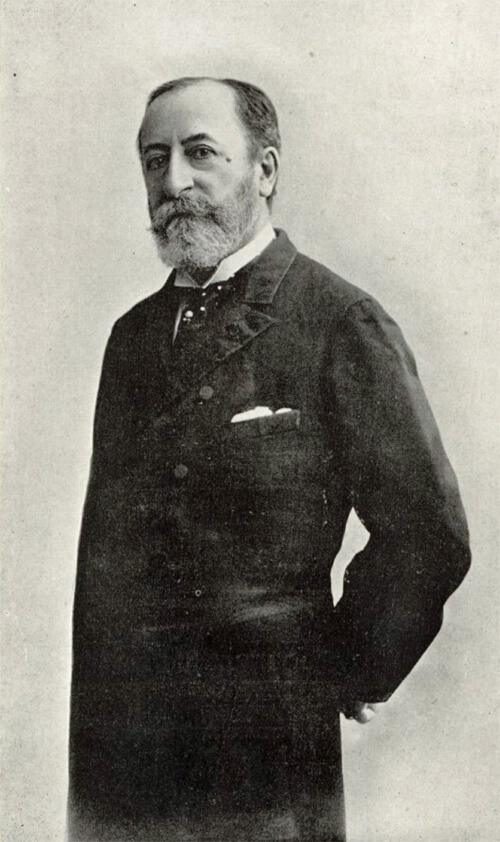

Camille Saint-Saëns: An Underrated Master

Composers’ reputations come and go, often with little justice. Surely one of the most chronically underrated composers in the canon is Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921). This Frenchman was a remarkable figure by any measure. To start, he may have been the most impressive child prodigy in the history of music. At the age of two-and-a-half he was picking out tunes at the piano, at three he composed his first piece, at five he was studying the orchestral score of Mozart’s Don Giovanni and gave his first piano recital. In addition to becoming a brilliant pianist and organist—Liszt considered him the finest organist of the day, Saint-Saëns was also one of the most widely cultured composers of all time. His interests included astronomy, archeology, geology, botany, and mathematics; he wrote poetry and a play as well as music criticism; he was a restless world traveler (he died while on vacation in Algiers). Saint-Saëns’ lifetime of 86 years spanned nearly the entire Romantic era as well as the dawn of twentieth-century modernism. Born eight years after Beethoven died, he lived long enough to attend the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and became the first important composer to write movie music (for a 1908 silent film).

Amid the nineteenth-century battles between musical “conservatives” and “progressives,” Saint-Saëns maintained a healthy balance. Early on he boosted the ultra-Romantic works of Liszt and Wagner and composed programmatic tone poems in emulation of those composers. But for the most part Saint-Saëns was—like Brahms—a “Classical Romantic.” He revered Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven and the classical French tradition. His music has clear outlines, transparency, and a keen sense of form and proportion. It possesses the classic French qualities of restraint, refinement, and charm, avoiding emotional excess. He has been dubbed the “French Mendelssohn.”

Yet Saint-Saëns’ music—like Mendelssohn’s—has often been looked down upon or damned with faint praise. Critics will concede that Saint-Saëns’ music is expertly crafted and tasteful, but—here comes the damning phrase—it lacks “depth.” The implication is that his music is all elegant superficiality. Part of the problem is that we tend to judge all music by the aesthetic norms of German Romanticism. The French aesthetic is less well understood, and we would do well to come to terms with it.

Saint-Saëns once said that “the artist who does not feel completely satisfied by elegant lines, by harmonious colors, and by a beautiful succession of chords does not understand the art of music.” This is a perfect summation of the French musical tradition, which delights in the pure pleasure of the art and is less interested in extra-musical considerations. Donald J. Grout said of this tradition that it “rests on a conception of music as sonorous form, in contrast to the Romantic conception of music as expression. Order and restraint are fundamental…above all, [French music] is not concerned with delivering a Message, whether about the fate of the cosmos or the state of the composer’s soul. A listener will fail to comprehend such music unless he is sensible to quiet statement, nuance, and exquisite detail…” The American composer Ned Rorem put it more succinctly and wittily: “If French music is profoundly superficial, German music is superficially profound.”

Thus the German Romantic bias in our musical culture has been an obstacle to a wider appreciation of Saint-Saëns. Another problem is that Saint-Saëns is best known for his most lightweight music—such as Danse macabre and Carnival of the Animals—rather than for his more serious efforts. True, a handful of his weightier works are in the repertoire: the Organ Symphony, the First Violin Sonata, and two or three of the concertos as well as the opera Samson and Delilah. But what about the Piano Quartet in B-flat or the Septet in E-flat for Trumpet, Piano and Strings? This author recalls singing Saint-Saëns’ Tu es Petrus in his church choir once on the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. Why do we not hear more of his sacred choral music, of which he wrote a great deal?

A good place to start exploring Saint-Saëns is the delightful Septet in E-flat. It was written in 1881 for a Parisian music society called La Trompette—hence the unusual scoring of trumpet, string quintet, and piano, unique in music literature. The piece pays homage to the Baroque in a suite-like design; there is a “preamble,” a minuet, an “intermezzo,” a gavotte, and a spirited finale. The Septet presages the “back to Bach” movement of the twentieth century, with the trumpet crowing fanfare-like motifs. The work is filled with a luminous clarity and unpretentious charm.

The Piano Quartet No. 2 in B-flat, premiered in 1875, is a substantial (over thirty minutes) and finely crafted work. The memorable opening theme is as light as a spring breeze. The quartet is unorthodox in that it lacks a true slow movement, replacing this with ingenious contrapuntal workmanship, much of it based on chorale-like tunes which could have come out of Bach.

The violin sonatas are both excellent works, though very different in character. The First, in D minor, is Beethovenian in its passion and structural coherence. The Second, in E-flat, is a less flashy work whose beauties are subtler, rewarding multiple hearings. The slow movement is a sublimely veiled, floating andante. The two violin sonatas could be said to sum up respectively the “Romantic” and “Classical” sides of Saint-Saëns.

The essentials of Saint-Saëns’ art can be heard in the graceful little Elégie for violin and piano, which he wrote in the latter part of his life, in 1915:

In sum, Saint-Saëns was a better and more important composer than he is often given credit for. In a way he was a gigantic bridge binding together the Classical, Romantic and modern eras. His expressive range encompassed both a contrapuntal vitality reminiscent of the Baroque masters and shimmering, hazy slow movements that conjure up the canvases of the French Impressionists. He was a formative influence on Ravel, and his witty evocations of eighteenth-century styles anticipated the neoclassicism of Stravinsky and Poulenc. Saint-Saëns indeed had a wonderful sense of humor—not a conspicuous feature of much Romantic music—which shows itself in two of his most popular pieces, Carnival of the Animals (a “grand zoological fantasy” for two pianos and orchestra) and Danse macabre (a tone poem in which skeletons are raised from the grave and perform a dance on All Hallows’ Eve). But it is his serious, abstract works—especially his chamber music—that show Saint-Saëns at his Gallic best and assure his place among the great composers.

This was originally published with the same title in The Imaginative Conservative on June 8, 2017.