Knowledge and Evil

“I know not well how to retell how there I entered / so filled was I with slumber at that point […] And as he who […] having exited the lake to shore, […] turns to the dangerous water and inspects, / so did my spirit, that still bent fleeing, / turn rearward to admire the step / that never yet allowed person to live.”[1]

When modernity teaches us that knowledge is power, which is to say that it empowers us, as a tool, to overcome evil, it leaves us asking ourselves if power, in whatever guise it might be stored, is sufficient to overcome evil, so that evil would coincide with meekness.

Classical Platonism’s defense of knowledge against evil—the ancient retracing of knowledge to the eternal—should not blind us to what it does not strictly entail, namely our capacity to bridge the hiatus between good and evil. If Socratic knowledge is knowledge of eternal things, then it is not knowledge of evil, but of the good, which, alone, does not resolve the human or political problem of freedom. Solid, even unassailable anchorage in the good is necessary to live freely, but freedom is a living challenge that no knowledge can dispense us with, as human beings. Yet, for Socrates knowledge or wisdom is not a means to an end: Socrates does not seek knowledge for moral purposes. His freedom points back to the wisdom he loves, the community with the good that he cherishes above all things. If we need knowledge to be free, that knowledge must be somehow “forgotten” or in need of being “recollected”. Could freedom be anything other than the “recollection” of wisdom? Could it be anything other than a return to the (intelligible) good, the good of communion with and in pure intelligibility? Our good would then be a telos entailing a multitude of daily challenges that each one of us faces and that are finally and fully redeemed only in the highest sense of freedom, truth and life.

If our (re)turn to the good sets us free, if it redeems our freedom by perfecting it, or by converting it into virtue and thereby into an armor against evil, then knowledge and freedom are not only eminently compatible, but providentially inseparable. Freedom will “teach” us that knowledge is alive (that, as a certain determination, “dead” knowledge is but a shadow, even a distraction from living knowledge, from “the life of the mind”), just as knowledge will surface as freedom’s living guide and proper end. By turning to knowledge as communion with the good and indeed as the good as intelligible communion (Plato’s “community of ideas”), freedom elicits a moral fiber, justifying itself in the face of any evil impulse, above all that of tyranny.

Without presupposing providence as both a promised land and a living, if only hidden presence, freedom would hardly be sustainable. Freedom does not require, then, a defense offered ex machina, or handed down to it by any given authority; all that freedom requires is its own inner resources, as freedom turns to its proper end.

Knowledge, or communion with all that is good, or finding all things within thought/mind, does not preclude betrayal of our calling as human beings, of our heroic nature. Wisdom or science might even distract us from our foremost calling to seek the good as something eminently lost, or as the primal presupposition of our present condition and so of our being in any given place. Why do we find ourselves anywhere, whether we consider ourselves to be wise, or ignorant? How did we arrive to the place where we currently stand? Knowledge does not answer that question, insofar as it remains somewhere: knowledge cannot account for its own genesis, its background (“prehistory”), its context. Knowledge presupposes something other than knowledge, something unmeasurable, unquantifiable in virtue of which knowledge can be attained to, as a treasure island might be. We cannot know the waters to be crossed in order to reach that “island,” or to reach the feet of the “mount” of wisdom (to echo Dante). Something other than intelligibility is responsible, or at least co-responsible for our “fall” into a condition of ignorance. The recovery of knowledge distinguished from mere opinion (or the mere appearance or pretension of knowledge) presupposes something that cannot be fully known.

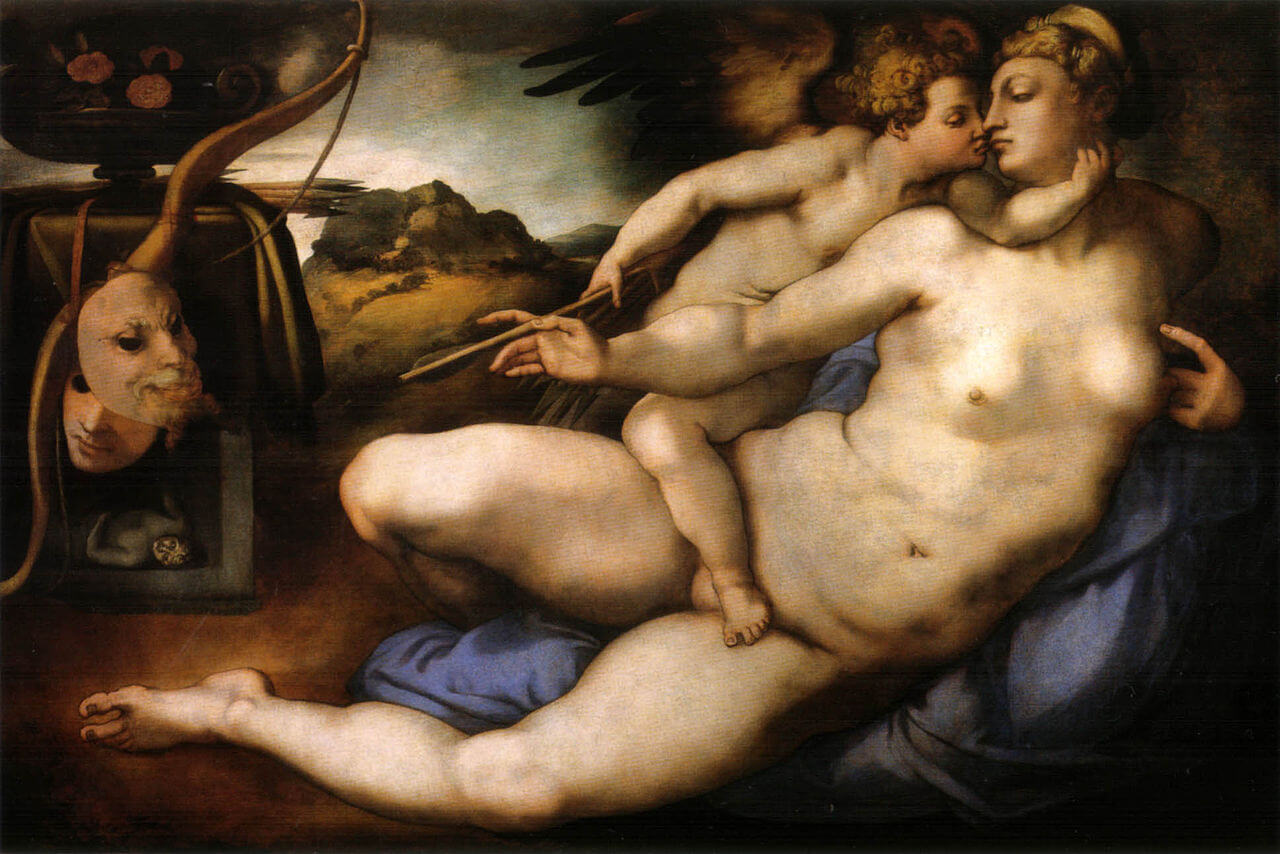

What does knowledge know? Beauty, as the good insofar as it is known: the order of parts making up a whole. Now, to know beauty, to know fully, entails grasping the conditions of possibility of beauty. Beauty alone, the face of the good, is not enough. To know beauty is not merely to see beauty; we must see beauty in the light of its roots—its genesis, or what it takes to constitute the beautiful object of knowledge. The quest for knowledge calls us to explore the ascent to beauty from the ugly, the amorphous, the beastly. Knowledge of, or genuine community with beauty, presupposes the effort of gathering the ugly into the beautiful, carnal decay into the permanence of spiritual flourishing. In this respect, knowledge entails the sacrifice, death, or conversion of the flesh into the intelligible, the transposition of physical opacity onto “transparent” grounds, where the mind or thought attains to itself in ecstatic satisfaction. Here, beauty is conquered as it looks back upon desire, in grateful recognition and unconditional dedication, mirroring desire itself, or rather desire’s own perfect fulfillment: the yearning mind itself, acknowledged as master that does not err (Dante, Inferno 2).

Upon communing with beauty, desire converts into thought. Thought: desire that explores freely the content of its object.

Thought gives itself back to beauty only insofar as beauty gives itself back to thought. Thereupon, thought accomplishes itself beyond itself, letting the light of its creative depths distinguish anew all that is good from all that falls short of goodness. Yet, this triumph of thought is not thought’s last word, as the Gospels remind us upon “tying” the Incarnation to the Cross, and the embrace of Venus and Cupid to the Pietà. Thought and beauty do give themselves to each other; their communion does illuminate our World; but in so doing, far from resolving problems, the “mystical marriage” of Beauty and Love exposes the permanence of problems and therewith our calling to heroically transcend delight—to enter a limbo where beauty (product/projection of mind/thought) is met as a poetic illusion granting us no satisfaction. There, thought is crowned by neither mirth, nor thorns, but by the liberty to pierce, in doubt, both any and all triumph, any and all satisfaction, and any and all disaster. For, the “marriage” consummated, the mind finds itself projected, not altogether into beauty, but through beauty, before totality as a fundamental riddle.

The discrete contents of mind have been “sacrificed” on the altar of beauty, if only for a fleeting moment, as the mind—echoed by Orpheus before a Euridice beyond all reaches—caught a glimpse of itself in its disappearing. We experience knowledge, then, from behind, as it were, or in its flight into the obscure: knowledge as eclipse, even as fall into ignorance; knowledge as impossibility—beauty as loss, as death. Amore–Morte. The beauty we love, the consummation of knowledge, is one with its abolition; its eternity shows itself under the heading of E. A. Poe’s “Nevermore,” leaving us facing ever-anew the challenge of the hero forced to live without beauty, without wisdom, without satisfaction, without love; moved—in the face of a death coinciding with divine beauty—to desire infinitely, heroically, to fill the void left by beauty’s departure with the mind’s own virtues, thought’s discourse, the mind’s creation of mirrors reflecting beauty in the penumbra of allusions disclosing in the act of concealing, proffering in the act of hushing, imitating thus the work of Nature, the work of totality itself.

Knowledge is not enough, then, for us, as we require also the living exploration of the genesis of knowledge—a heroic journey through ignorance as the indetermination of knowledge. Now, that exploration entails the poetic recreation of knowledge on the grounds of ignorance, the reconstitution of the mind (“enlightenment”) on “material” foundations.

This original “recreation” has been eclipsed in modern times by the project of consolidating poetic knowledge as “Science”. Classical poetry has been reconceived in technological terms, not as producing mirrors of eternity, but as producing a world or “Tower” in which we can live without any reference to the eternal. Modern man explores the “pre-history” or context of knowledge as a justification for human creativity, rather than as the opportunity—divinely provided, or otherwise—to transcend (the compulsion of) human creativity, no less than its “sub-human” underpinnings.

Modernity replaces a classical divine “knowledge of knowledge,” or rather the classical ascent from 1) the quest for beauty to 2) the heroic quest for the truth of beauty, with a novel synthesis of knowledge and ignorance, as of “essence” and “existence”: where it is assumed to be originally unknowable, the genesis (now, mere “possibility,” or power) of knowledge can be conceived to confirm all “knowledge” ensuing from it, especially where all knowledge is seen to converge into a totalizing integration of its preconditions. Here knowledge is consummated in the unification of its material conditions—a unification that is, at once, an actualization. Knowledge of beauty is now at once knowledge of truth, which is to say, of beauty that has become truth itself, thereby resolving the discrepancy between the formal conditions of possibility of knowledge (conceptual “universality”) and the phenomenal objects of knowledge (physical “particularity”).

Our classics offer us an alternative promising to serve as antidote to the modern crisis of both beauty and truth: ascent from knowledge of beauty to knowledge of the good as the truth about beauty. Even the most beautiful integration of evil into the good does not spare us the challenge of defending the ascent or return to the good—of living out the task of restoring appearances in the face of the threat of evil, and thus of never taking beauty for granted. Beauty as such will not be a synthesis of good and evil; it will not signal the overcoming of the threat of evil as an original and thus permanent challenge. The separation of knowledge and virtue will not be overcome by integrating evil into the good (Machiavelli), or by looking down upon the threat of evil (especially as incarnated by the objector to the project of fully integrating evil in the good society) as a mere, or “radical” evil (Kant).

What with modernity tends to be regarded as signaling an unforgivable betrayal of the good, constitutes for our classics the essence of freedom. The old freedom is incompatible with the new, modern freedom and its end, namely “mastery” as fueling and channeling of nature. Machiavelli’s “new ways and orders” (modi e ordini nuovi), not unlike Galileo’s nuova scienza, entails a new way of governing nature by coopting it to serve the project of building a world in which good and evil coincide, or in which their difference becomes practically irrelevant. Modern man is to flee evil in the very act of fleeing the good; he tries to overcome evil by conceiving it as a necessity bound to a good now conceived in merely conventional terms. The modern world finds its inception in the exorcism of an evil that is supposed to be at once necessary and expendable—necessarily bound to the good (i.e., to what we want naturally) and ultimately morally insignificant, even banal. How is modern man supposed to overcome evil? Not by choosing the good, but by dismissing the good as a conventional trifle, a “superstition,” a “cultural” fabrication. Only by “killing God” (the good God of the Bible) can modern man escape fear of evil. Or so he believes. For, no sooner has God been effaced, no sooner has modern man erased the Christian face of God than he is confronted with an indefinite multiplicity of “new” evils, not to speak of the entire universe as the face of evil. No longer bespeaking God through man, the universe comes to signal or reflect man’s radical vulnerability. Evil as the counterpart of good, evil as avoidable threat has disappeared, yielding to evil as all-pervasive necessity—evil as natural, as thoroughly acceptable, as a fate to embrace, to love. Amor fati. The classical, pre-philosophical marriage of desire (eros) and beauty (in the person of an immaculate Venus) is replaced by a post-philosophical concubinage of desire and evil—an affair aimed at exorcising evil by embracing it in a subversive parody of Christian forgiveness.

The modern relativizing of the good, or the replacement of the good with the society of commercial “goods,” is retraceable to a Machiavellian pact with evil conceived as inevitable result of exposure to the indetermination of the good. For Machiavelli there is no divine anchorage, no providence, allowing us to resist evil when faced with its possibility. That possibility is not to be understood in the light of a divine mystery, but in the darkness of infernal absurdity. It would be easy for Machiavelli to adhere to the good as absolute, were it not for the man’s love of wisdom—for his desire of totality.

Having faced that which lies beyond the good determinations or limits of his world, Machiavelli succumbs to the suspicion that all good is bound to a concomitant evil, or that the good needs evil to be completed, much as authority needs reason. Does evil provide authority with its raison d’être? Do we not conceive and even love boundaries for the sake of escaping evil? Dissatisfied with our “plebeian” fear, Machiavelli attempts a “noble” feat: to love boundaries, to be “pious,” for the sake of embracing evil. A new piety is inaugurated as means to conquer evil—nature itself—as a harlot. Accordingly, religion should no longer provide shelter from existential indetermination; rather, it should be used as a mask of all that older modes of religiosity would designate as vice. Modernity rejects the “old” denigration of evil, as a sign of unnecessary weakness, especially intellectual weakness. Premodernity now emerges as the infancy of a man struggling for emancipation from prejudice against evil, gradually learning to feel at home in a universe devoid of good, a godless “nature” in which man is the creator of all goods.

Modern man’s self-divinization is bound to his conception of the universe as what premodern man would regard as evil: a place where “God is dead”. It is in the context of God’s death that modern man “resurrects” divinity and therewith religion as mask of, or distraction from evil. Modern man must live as if God were alive, even though he must understand that God is dead, which is to say that man cannot count on any divine providence. In God’s de facto absence, man must establish a new alliance; he must learn to live with (material) indetermination by embracing it as his destiny—a destiny that redirects his life, redefining man as the breaker of boundaries, the challenger or all ends, the subverter of all inheritance. No longer passively subject to an evil nature, modern man ceases to consider nature as evil: he “forgives” nature for a fault that early modern thinkers had attributed to her, in the first place. Nature is for us, now, extraordinary, marvelous, fascinating, daunting, awesome, powerful. Most importantly, nature can make us powerful. By “mating” with nature, modern man can transcend his earlier condition, discovering his true fate at once as servant and master of nature. By giving into what earlier ages would have despised as evil, modern man acquires powers earlier ages could at best dream of. The Faustian sacrifice of an “old” soul is justified by the acquisition of a new “soul”—a new life “beyond good and evil”. Whence modern man’s compulsion to cease listening to previous ages; for they carry the unbearable reminder that modern man’s greatness is his pettiness, that his virtue is no more than the veil of vileness, that his “excellence” is but a vain pretense.

It is exposure of the fragility of modernity’s “solution” to the classical tension between knowledge and virtue, that exposes us anew to the classical challenge of heroism. As we learn to see the new in the light of the old, an “old” heroism comes to our attention as responding to the crisis of the modern solution. Just as modern “super-heroism” (modernity’s superseding of classical heroism) entails the radical absence of divine providence, so does classical heroism entail the presence of the divine in death: the old hero turns to death, not as an evil to be converted into the production of goods, but as the place where the divine calls or tests us to reject evil. Accordingly, just as modern man supposes himself free by overcoming death, so does his classical predecessor see himself free by dying in God’s hands, as it were. Modernity rejects the very possibility of this endless death—a death suspended in eternity, a death coinciding with a resurrection. Given its rejection of classical divine providence, modernity considers the transcendence of death possible only in terms of the integration of death into a “virtual” world in which we all pretend to be immortal, or in which we all pretend that death is simply “a part of life,” a fact that is completely incorporated in life’s progressive impulse, or creativity. As modern or enlightened men, we are supposed to accept death so as to fit in an “open” society that uses death, our very mortality, as a steppingstone for the society’s own development. Death is conceived, here, as sign that our new society constitutes our only salvation, the only horizon on which we can still hope. Beyond our society, then, only despair. Nulla salus; not because our society is our mirror of eternity, but because, in the absence of eternity, our society constitutes our only alternative to meaningless or violent death.

It is only by an act of “symbolic abstraction” that modern man comes to conceive his society as a retreat from Heaven. Only a new “ideal” mode of social interaction—interaction mediated by an “ideal”—could allow us to dispense with divine mediation. Where the divine is replaced with an ideal, life becomes progressive. What defines our society is thereupon, not trusting openness to eternity, but closure upon an ideal to be realized; not consolidation (of order) open to disinterested interpretation, but “instrumental” interpretation open to consolidation. The eternal is now symbolically or geometrically established in advance (Spinoza), as a steppingstone for the rise of a new mode of interpretation, a new way of relating to order. The new “eternal” is a nominal representation of an evolving being, just as Spinoza’s God is none other than nature—both naturans and naturata, both in-itself as noumenal (Kant) pure creativity (Nietzsche), and out-of-itself as phenomena to be integrated in History. The new society has rejected, then, the eternal in its classical sense, replacing it with an ideal representation to be incarnated by integrating or “conquering” nature. The classical integration of nature into an artful mirror of eternity yields to a new integration of nature into art as an end in itself—art using nature to grow, or to empower itself. Our art is no longer supposed to be the vicar of God through the imitation of divine art, but the master of nature itself. We do not strive to guide nature—the bodily—to liberation in the light of a transcendent eternity, but to possess nature for the sake of giving substance to our dreams. Therein is the key to the modern progressive impulse, a drive to flee the absence of non-symbolic eternity. In the face of the ultimate impossibility of a return, what is absolutely primary is a compulsion to move “forward,” or to escape. “In the beginning” is Evasion. Distraction, or complete creative integration into a universe of distractions, is all.

Modern knowledge is progressive in the respect that it moves constitutionally away from the very possibility of an unconditional return, and thus away from the idea of the Good that classical Platonism has always systematically stood for. Knowledge is no longer understood in terms of a recovery of an original good, but in terms of the discovery of an original absence of integrity. “In the beginning is brokenness”—a condition that is “clinically” appealed to aside from any traditional morality for which brokenness, as heresy, is directly associated with evil. For modernity, brokenness or the absence of an original good is more closely associated with goodness than with evil, even as it cannot, by definition, be the good. For brokenness can be integrated into a future reality, a future society making strategic use of brokenness in the interests of the society’s own free constitution.

Freedom, as opposed to classical virtue, is the master-key to modernity’s conception of knowledge. As the Machiavellian tradition shows distinctly, beyond classical notions of good and evil, freedom demands of us the strategic exercise of both good and evil in the interests of a new good coinciding with the liberation of our creativity, the free exercise of our power to create—to be like God. And yet, insofar as modern freedom empties itself, as if triumphantly, into an imitatio dei sine deo, insofar as modern freedom unfolds into a sublime pretension, it destines itself to crisis. The freedom that, on one side of the coin of modernity, is critical to the establishment of knowledge, is reduced, on the other side, to a knowledge confirming the illusory nature of freedom.

Classical antiquity points us beyond our contemporary crisis, to discover the mutual compatibility of freedom and knowledge, where the former coincides with prudence and the latter is a beautiful, poetic mirror of divine transcendence. Here, beauty is a dangerous challenge that men cannot live without: a danger, for we so easily mistake the appearance of the good for the good itself; a necessary challenge, since we ascend to the good only in the mirror of its appearance. What saves us from falling prey to the allures of beauty is a medium checking the pleasure we take in falling in love. That medium is what classical antiquity praises as human wisdom, the prudence that man bears supreme witness to in the form of laws. Yet, laws themselves are not immune to being mistaken as alternatives to the challenge of rising from beauty to the good itself. The return from law to prudence becomes a necessary step for us to return to the challenge of beauty—the challenge of returning to the good itself. Prudence, whose majestic echo is law, reminds us that the good is, for us, primarily, not an object of enjoyment, but the object of a quest, indeed of all searching. We are born incomplete, inadequate, in search of the good; our birth is the threshold of a path to the good, a path along which we catch glimpses of reflections of the good in a cosmic game of mirrors that prudence alone can help us take advantage of, disclosing, along our way, the inadequacies of all beauty, of all satisfaction, of all consummations—not so that we may live in a universe devoid of beauty, but so that we may awaken to our proper place or condition and the unique task it entails: to embody the necessary covenant between beauty and the good.

Notes

[1] “Io non so ben ridir com’i’ v’intrai, / tant’era pien di sonno a quel punto […] E come quei che […] uscito fuor del pelago a la riva, […] si volge a l’acqua perigliosa e guata, / così l’animo mio, ch’ancor fuggiva, / si volse a retro a rimirar lo passo / che non lasciò già mai persona viva” (Dante, Inferno 1).